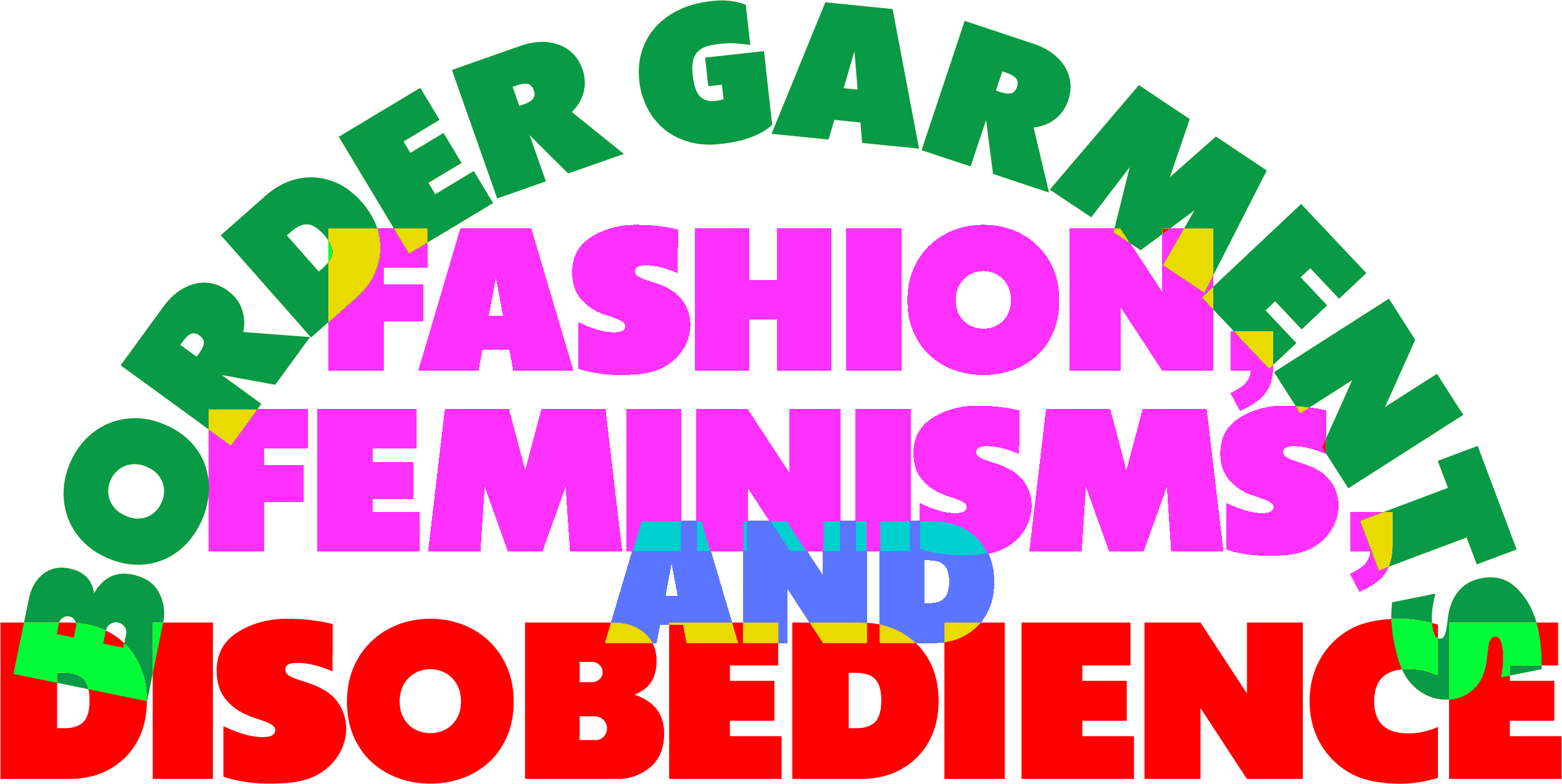

Special Issue Edited by The Border Creatures: Loreto Martinez, Tamara Poblete, Ellen Sampson, and Karen van Godtsenhoven

The Border Creatures

The Border CreaturesTABLE OF CONTENTS

- Letter from the Editors

By The Border Creatures

-

Queer Fashion Against Pinkwashing: An Interview with Trashy

By Roberto Filippello

- Embracing the Stigma: “Freedom Cunts” and Their Destigmatization and Empowerment

By Hennessy Eileen

- Between the Public and Private: Transformative Agency of Wearable Forms of Protest

By Lucia Cuba

Versión en castellano - Deviant Dress Codes: Negotiating Spaces in the Sartorial Sculptures of Carlos Villa and Leeroy New

By Weiqin Chay

- JIWASA / NOSOTRAS

Balbucear gritando / Gritar balbuceando

By Movimiento Maricas Bolivia

-

Clothing and Adornment as Resistance:

Disobedient Bodies and Aesthetic Expressions in Paraguay

By Jazmín Ruiz Díaz Figueredo & Kira Xonorika Versión en castellano - Fashion as Political Statement in Post-Revolutionary Iran

By Azadeh Fatehrad

- The Clothes of Violence 1973-1990

By Pía Montalva

Versión española - Made in the Philippines: An Interview with Vintage Fashion Shop Glorious Dias

By Bianca García

-

Visual Narrative Memories from the Gender Border: Performances of Dressed Bodies

By Violet Arvin Casoni, Carolina Brandão Piva,

& Luciene de Oliveira

Versão em português - Pain at the Border: The Feminization and Exploitation of Textile Work in Mexico

By Mariana Parra González

Versión española -

A Visual Script on Borders and Borderline Garments

By Anita Puig & Giancarlo Pazzanese

Versión española

Letter from the Editors

We write this introduction to “Border Garments: Fashion, Feminisms and Disobedience” just over two years after our first conversations about developing a special issue which addressed the surge of protests and uprisings against neoliberal patriarchal capitalism in Latin America. In light of new and ongoing crises in women’s rights across the globe, with daily news about state killings of women in Iran, and violence against women and LGBTQIA+ persons in Afghanistan, Russia, Syria, the USA, Qatar, Hungary and Poland, it has at times felt futile to focus on fashion and garments as a tool for disobedience. Yet the role of the dressed body as sites and catalysts of political resistance has never been more evident and we hope that however small, this issue can amplify subversive voices in the face of oppression across the world.

The title of this issue and its broader conceptual framework stem from Gloria E. Anzaldúa’s seminal text Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, which examines the Latinx and Chicana experience through the lens of racism, colonialism, gender and class identity. Anzaldua writes about the border between the US and Mexico as:

“una herida abierta (an open wound) where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds — the lifeblood of two worlds merging to form a third country — a border culture. Borders are set up to define the places that are safe and unsafe, to distinguish us from them. A border is a dividing line, a narrow strip along a steep edge. A borderland is a vague and undetermined place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. It is in a constant state of transition. The prohibited and forbidden are its inhabitants.” [1]

Borderlands, teeming with transition, as an in-between space of resistance against control, are thus also full of potential. Similarly, garments, with their potential for transmutation from their artistic-objectual condition to their ability to transmit a specific discourse, can generate through their bodily actions crises of meaning around coloniality, sex/gender, class and race.

Figure 1. Gloria Anzaldúa by Annie F. Valva

Figure 1. Gloria Anzaldúa by Annie F. ValvaThe use of garments as means for counter-hegemonic ideas is certainly not new and this special builds on the already extensive academic literature on the intersections of dress practices and politics including the work of Djurdja Bartlett (East), Regina Roots (Latin America) and Pía Montalva (Chile) and into dress and decoloniality, such as the work of Sarah Cheang (Asia) and Erica de Greef (Africa). [2] The demonstrations in which clothing and protest have been allies in political-social processes have been too multiple to list but include the Incroyables, the Bloomerites, the Suffragettes, the Aesthetic movement and its LGBTQIA symbols, the Zoot suit, the miniskirt, and the dress code of the Black Panthers. More recently the Pussyhat movement, female celebrities dressed in black at the Golden Globe Awards in honor of Time’s Up / #MeToo, female politicians wearing white in reference to Suffragettes, the use of clothing in Black Lives Matter protests and with women in Iran cutting their hair in solidarity with the deceased Mahsa Amini all highlight the ways that altering and politicizing one's appearance has become a medium to disrupt and critique hegemonic structures. [3] In building upon these texts this special issue seeks to make visible design and making processes, theoretical frameworks and activism experiences which emerge from and take place in countries that are often excluded from the “canon” of fashion studies. The articles in this issue come from and addresses experiences of clothing protest and resistance in Peru, the Philippines, Paraguay, Iran, Chile, Brazil, Singapore, Bolivia, Mexico and Palestine and through their works the authors highlight these territories as legitimate places of knowledge production.

The original impulse for this issue came from the courageous wave of protests in Chile and more widely in Latin America since 2018, which acted as beacons of liberation and hope in the global women's struggle. Both before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous countries (in particular those across the Global South), saw a surge of protests and uprisings, against neoliberal patriarchal capitalism and oppression: interventions in the public space mainly by feminist collectives and gender-sex dissidents who put clothing at the center of their action strategies. Despite global the confinements of multiple lockdowns, these manifestations were not silenced, but instead resurfaced through social networks; prepondering a resignification of these garments, their materiality and the manual techniques associated with the female space (sewing, embroidery, knitting, etc.), where bonds of sisterhood are woven, and generational knowledge of hand work is disseminated. These new forms of protest have come to “produce” politics, or even to embody the political in performance and mass mobilization to the extent that feminist movements have marked the political agenda of the continent. This capacity of Latin American feminisms for action can be traced to the practice of a large-scale popular feminist movement that the Bolivian anarcho-feminist, María Galindo, has called “feminismo intuitivo” (intuitive feminism) in her last book Feminismo Bastardo. [4] According to Galindo, this is a type of feminism that doesn’t come from academic instruction, but from the great ability of women to read their own history and generate ruptures of a political nature. Galindo suggests that this feminism is, in effect, the one that is changing the patriarchal structures of society.

Taking the events of 2018 as a starting point and inspiration, this special issue brings together a diverse group of scholars to explore a dress practices which cross and recross borders spanning design, photography, making, reuse, artistic practice, and performance. These papers challenge the idea of clothing as something passive or decorative framing it instead as a powerful and political form of material culture which can both empower and do great harm. Starting with design and making, Roberto Filipello (Italy, Canada) interviewed the activist design collective Trashy about their design practice as resistance in the face of colonial and LGBTQIA+ oppression in Gaza. In “Clothing and Adornment as Resistance: Disobedient Bodies and Aesthetic Expressions in Paraguay,” Jazmín Ruiz and Xonorika Kira (Paraguay) bring us closer to disruptive proposals in contemporary Paraguayan fashion, focusing on two brands that dismantle the binary order of gender: Deiv/Bassen and Baby Trauma. Bianca Garcia (Philippines) introduces us, in an interview, to the transformative community evolution of the work of the queer Filipino artist and designer Jodinan Aguillon and the profound impact that the precariousness of life, the Balikbayan diaspora and the pandemic had on this process. Whilst Mariana Parra (Mexico) interviews border workers about the circumstances in which they produce garments for major fashion brands, testifying to the brutal impact that precariousness, marginalization and exploitation imposed by the current capitalist system, conditions required for its perpetuation.

Violet Arvin Casoni (Chile), Carolina Brandão Piva, and Luciene de Oliveira Dias (Brazil) delve into trans performativity, situating themselves in the dictatorial contexts of Chile and Brazil through the photographic work of the artists Paz Errázuriz and Magdalena Schwartz and the artist Vasco Szinetar. From Latin America, Maricas Bolivia (Bolivia) approaches identity, sexuality and proper name from an indigenous decolonial position in the visceral poem-manifesto “Balbucear gritando / Gritar babbuceando.” Thinking about protest Lucia Cuba (Peru) proposes the activation of clothing as a political device in daily life in her production “Vestibles para/por la protesta,” a series of garments that, from the personal point of view of everyday life, makes visible and confronts complex social problems. The second article on protest by Eileen Hennessy “Embracing the Stigma: ‘Freedom Cunts’ and Their Destigmatization and Empowerment” was withdrawn from the issue over concerns for the author’s personal safety in the face of government tracking and censorship. The blank page symbolizes our tribute to the courage and strength of authors whose voices are currently being censored. Pía Montalva (Chile), in turn, in an exhaustive archival investigation, examines the role of clothing within the chain of production of violence in the Chilean civic-military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet (1973 to 1990), specifically, the who occupied two garments used to disable the body: the bandage and the overalls.

Figure 2. Maria Galindo by EDITORIAL MANTIS

Weiqin Chay (Singapore), analyzes the work of Leeroy New and Carlos Villa (migrant Filipino artists in the US) problematizing from fashion studies the role of clothing in the representation of diasporic identities. The moving photographic essay by Artist Azadeh Fatehrad (UK/Iran), delves us into the complexities of contemporary Iranian feminism through the relationship of women with the female Muslim veil in the 21st century. Anita Puig (Chile) and Giancarlo Pazzanesse (Chile/Italy/Netherlands) close by problematizing the very concept of border both in the proposed writing format and in the different cases they address, all focused on the intersection between the wearable and the border.

As editors, working with and amending others' words, we were conscious of the role of language as a tool for disobedience and liberation. In the chapter “How to Tame a Wild Tongue”, Anzaldua describes the process of being alienated from her mother tongue, and how, by keeping her tongue wild, she won’t let closing linguistic borders control her language. She continues to describe other “disciplining” instances where language purists try to hammer out the “border language” she shares with many Latinx immigrants. Anzaldúa shows the connection someone’s language has to their identity, and how the two go hand in hand. Given the dominance of the English language as the lingua franca of fashion studies, and the colonial histories and legacies of this dominance, we chose to publish this issue in dual language giving authors the option to write and publish in their mother tongue. as a feminist practice in the face of linguistic, patriarchal oppression. We want to thank the translator who made this possible, Alejandra Szczepania for the Spanish texts and the universities of Ghent (Belgium) and Northumbria (UK) for their generous funding.

In the process of editing this journal, we were confronted by the realities of censorship and personal danger to people who speak up. A contributing author asked to be removed from the issue because of government tracking and censorship dangers. We dedicate an empty page to this author and all other authors who might have wanted to contribute, but whose political situation makes it too dangerous to speak out. We stand in solidarity with those whose voices cannot (yet) be heard and remain hopeful for the future.

In conclusion, we would like to thank the courageous and disobedient authors for their contributions, the FSJ team for their patience, generosity, openness and hard work in making this issue a reality, and Sultana Bambino for her electric creativity and willingness to create a special graphic identity for this “Border Garments: Fashion, Feminisms and Disobedience” issue, which we are so proud of.

With this issue, we hope to connect the authors with new readers and inspire cross-cultural communities of enquiry, exchange and disobedience.

In solidarity and defiance,

The editorial team

As editors, working with and amending others' words, we were conscious of the role of language as a tool for disobedience and liberation. In the chapter “How to Tame a Wild Tongue”, Anzaldua describes the process of being alienated from her mother tongue, and how, by keeping her tongue wild, she won’t let closing linguistic borders control her language. She continues to describe other “disciplining” instances where language purists try to hammer out the “border language” she shares with many Latinx immigrants. Anzaldúa shows the connection someone’s language has to their identity, and how the two go hand in hand. Given the dominance of the English language as the lingua franca of fashion studies, and the colonial histories and legacies of this dominance, we chose to publish this issue in dual language giving authors the option to write and publish in their mother tongue. as a feminist practice in the face of linguistic, patriarchal oppression. We want to thank the translator who made this possible, Alejandra Szczepania for the Spanish texts and the universities of Ghent (Belgium) and Northumbria (UK) for their generous funding.

In the process of editing this journal, we were confronted by the realities of censorship and personal danger to people who speak up. A contributing author asked to be removed from the issue because of government tracking and censorship dangers. We dedicate an empty page to this author and all other authors who might have wanted to contribute, but whose political situation makes it too dangerous to speak out. We stand in solidarity with those whose voices cannot (yet) be heard and remain hopeful for the future.

In conclusion, we would like to thank the courageous and disobedient authors for their contributions, the FSJ team for their patience, generosity, openness and hard work in making this issue a reality, and Sultana Bambino for her electric creativity and willingness to create a special graphic identity for this “Border Garments: Fashion, Feminisms and Disobedience” issue, which we are so proud of.

With this issue, we hope to connect the authors with new readers and inspire cross-cultural communities of enquiry, exchange and disobedience.

In solidarity and defiance,

The editorial team

Notes: Letter from the Editors

[1] Anzaldúa, G. (2012). Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza. (4ta. Edición). San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

[2] Roots, R. (2014). “Fashion, Agency and Policy” (Section V), in Root, R, De la Haye, A, Entwistle, J, Black, S, Rocamora, A and Thomas, H. (Eds.) The Handbook of Fashion Studies. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

[3] “From heads, legs and underarms, to wigs and beards, and everything in between, the presentation, manipulation and daily experience of human hair plays a central and dynamic role within fashion, self-expression and the creation of social identity.” Cheang, S. (2008). Hair: Styling, Culture and Fashion. Berg Publishers.

[4] Galindo, M. (2021) Feminismo Bastardo. La Paz: Mujeres Creando.

[5] Sultana Bambino, the designer who created this issue’s visual identity, used Boldstrom type for the article headers, a font with a disobedient legacy of Black Panther newspapers and political posters.

Additional References

Cheang, S. (2021) “Section I (Introduction). Disruption in Time and Space”, in Cheang, S, De Greef, E and Yoko, T. (eds.) Rethinking Fashion Globalization. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 17.

Cheang, S and Suterwalla, S. (2020) “Decolonizing the Curriculum? Transformation, Emotion, and Positionality in Teaching”, in Slade, T and Jansen, A. (eds.), Fashion Theory, Volume 24, (6) Decoloniality and Fashion, 879- 900. doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800989

De Greef, E. (2020) “Curating Fashion as Decolonial Practice: Ndwalane’s Mblaselo and a Politics of Remembering”, in Slade, T and Jansen, A. (eds.) Fashion Theory, Volume 24, (6) Decoloniality and Fashion, 901-920. doi.org/10.1080/1362704X.2020.1800990

Montalva, P. (2013) Tejidos blandos: indumentaria y violencia política en Chile, 1973-1990. Santiago: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Roots, R. (2010) Couture and Consensus: Fashion and Politics in Postcolonial Argentina. Minneapolis: University Of Minnesota Press.

By Roberto Filippello

Roberto Filippello is a Killam Postdoctoral Research Fellow and a Teaching Fellow in Gender Studies at the University of British Columbia. His writing has been published in a wide range of academic journals, including Criticism, Third Text, Fashion Theory, and Australian Feminist Studies. His co-edited volume “Fashion and Feeling: The Affective Politics of Dress” is forthcoming in 2023. He can be reached via email at roberto.filippello@ubc.ca and on Twitter @RobertoFilippel

Roberto Filippello

Let’s start by introducing yourselves and your brand.

Shukri Lawrence

We are Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika and we are the creative directors of Trashy Clothing. Trashy is a Palestinian queer, political, subversive ready-to-wear label that plays upon the idea of satire. We like to call it an “anti-fashion fashion label.” We are interested in leading a consumer to buy our pieces not only for their design, but also for their stories, the story behind them. We very much rely on storytelling: in our collections we present ideas derived from everything we go through in our everyday lives as queer Palestinians in the Middle East. We focus on experiences that affect our bodies and our minds. The body is political! We are also largely inspired by pop culture and its intertwining with politics.

Roberto Filippello

Can you tell me about your “Pride for Pay” Spring-Summer 2021 collection?

![]()

![]()

Figures1-2. Looks from S/S 2021 “Pride for Pay” collection featuring the “inspection trousers” (© Trashy Clothing)

Shukri Lawrence

“Pride for Pay” explores what it means to be a queer person living in Palestine. More precisely, in the collection we explored the concepts of “pinkwashing” and “branding” [1]: the way Israel uses progressive movements such as the LGBTQ movement as a way to rebrand itself as a progressive country, and in so doing try to hide the crimes that are being committed against Palestinians, whether they are queer or not. We examine these ideas by playing with the body. For instance, we introduced pants that we call “inspection trousers”: through them we are sort of reclaiming our own bodies as Palestinians. Let me explain: a big part of Palestinian daily life revolves around going through checkpoints and being randomly stopped and searched. Our bodies are always touched by the unwanted hands of Israeli soldiers, which is a violent, intrusive, and uncomfortable experience especially for queer people. We wanted to confront that through our designs and to reclaim our bodies and our agency, so we decided to put big zippers on front, making the area of the zipper visible, as a way of saying “we decide when and where to unzip!” This whole idea of inspection and bodily agency will keep evolving with each collection. We are fascinated by the idea of branding, of what it means especially for high-end labels to brand themselves as “luxury,” making themselves unreachable, while also instilling in the consumers the desire to somehow achieve that by purchasing objects. In this collection we tried to experiment with the idea of branding by highlighting the image of a gay icon in the Arab world, Armenian-Lebanese pop star Maria [Nalbandian], whose face was found on all kinds of advertised products like cereals, lollipops, bubble gum, etc. through her music videos in the early 2000s. We made prints with her face and turned her into the spokesperson for cigarettes, Coke, and chocolate – all things that are “bubblegummy” but that are also harmful. Through this branding gesture we were basically playing along with, satirically, the idea of “pinkwashing”: branding and selling desirable products and ideas while obscuring what happens behind the scenes.

Roberto Filippello

The dynamics of bodily exposure at checkpoints and your use of fashion as an affront to military stripping practices made me think of Sharif Waked's Chic Point: Fashion at Israeli Checkpoints (2003).

Shukri Lawrence

Yes. We love his work. The images of his film were in our moodboard and are referenced in the collection.

Roberto Filippello

How were these concepts of pinkwashing and branding translated into the marketing campaign for the collection?

Let’s start by introducing yourselves and your brand.

Shukri Lawrence

We are Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika and we are the creative directors of Trashy Clothing. Trashy is a Palestinian queer, political, subversive ready-to-wear label that plays upon the idea of satire. We like to call it an “anti-fashion fashion label.” We are interested in leading a consumer to buy our pieces not only for their design, but also for their stories, the story behind them. We very much rely on storytelling: in our collections we present ideas derived from everything we go through in our everyday lives as queer Palestinians in the Middle East. We focus on experiences that affect our bodies and our minds. The body is political! We are also largely inspired by pop culture and its intertwining with politics.

Roberto Filippello

Can you tell me about your “Pride for Pay” Spring-Summer 2021 collection?

Figures1-2. Looks from S/S 2021 “Pride for Pay” collection featuring the “inspection trousers” (© Trashy Clothing)

Shukri Lawrence

“Pride for Pay” explores what it means to be a queer person living in Palestine. More precisely, in the collection we explored the concepts of “pinkwashing” and “branding” [1]: the way Israel uses progressive movements such as the LGBTQ movement as a way to rebrand itself as a progressive country, and in so doing try to hide the crimes that are being committed against Palestinians, whether they are queer or not. We examine these ideas by playing with the body. For instance, we introduced pants that we call “inspection trousers”: through them we are sort of reclaiming our own bodies as Palestinians. Let me explain: a big part of Palestinian daily life revolves around going through checkpoints and being randomly stopped and searched. Our bodies are always touched by the unwanted hands of Israeli soldiers, which is a violent, intrusive, and uncomfortable experience especially for queer people. We wanted to confront that through our designs and to reclaim our bodies and our agency, so we decided to put big zippers on front, making the area of the zipper visible, as a way of saying “we decide when and where to unzip!” This whole idea of inspection and bodily agency will keep evolving with each collection. We are fascinated by the idea of branding, of what it means especially for high-end labels to brand themselves as “luxury,” making themselves unreachable, while also instilling in the consumers the desire to somehow achieve that by purchasing objects. In this collection we tried to experiment with the idea of branding by highlighting the image of a gay icon in the Arab world, Armenian-Lebanese pop star Maria [Nalbandian], whose face was found on all kinds of advertised products like cereals, lollipops, bubble gum, etc. through her music videos in the early 2000s. We made prints with her face and turned her into the spokesperson for cigarettes, Coke, and chocolate – all things that are “bubblegummy” but that are also harmful. Through this branding gesture we were basically playing along with, satirically, the idea of “pinkwashing”: branding and selling desirable products and ideas while obscuring what happens behind the scenes.

Roberto Filippello

The dynamics of bodily exposure at checkpoints and your use of fashion as an affront to military stripping practices made me think of Sharif Waked's Chic Point: Fashion at Israeli Checkpoints (2003).

Shukri Lawrence

Yes. We love his work. The images of his film were in our moodboard and are referenced in the collection.

Roberto Filippello

How were these concepts of pinkwashing and branding translated into the marketing campaign for the collection?

Figure 3. S/S 2021 “Pride for Pay” campaign

Omar Braika

What we did for the campaign was to stage a pool party that calls to mind the pool and beach parties that take place in Tel Aviv. In 2005 the Israeli government released a campaign called “Brand Israel” to promote the country in the LGBTQ market, using magazine covers and all kinds of advertisements to promote Tel Aviv as a gay haven. We played with that idea of a Tel Aviv pool party as an emblematic image of “Brand Israel,” using the iconic imagery of luxury excess created by Steven Meisel for Versace in the 1990s as a visual reference, and contaminating it with elements like handcuffs and molotov cocktails. The models look like they are having fun, posing, hanging out and lying on the floor, but if you look closely you see they are actually being arrested. We wanted the polished and perfect branding, landscapes, scenery, and fashion to distract the viewer, but if you observe more deeply you notice that there's something wrong and unexpected with what you're looking at.

Roberto Filippello

So this collection is a queer staging that exposes the hypocrisy of the State of Israel, which deflects attention from the occupation through its neoliberal self-branding politics.

Omar Braika

Yeah, it's definitely showing that. But at the same time we wanted to take the angle of our own lived experience as queer Palestinians. You know, Palestinian queers living in Tel Aviv or in the West Bank are not granted any privilege for being queer. We wanted to highlight Israel's false narratives.

Roberto Filippello

You mean the false narrative that Israel is welcoming toward queers, and specifically Palestinian queers, right?

Omar Braika

Yes, we wanted to say “No! This is not heaven or the hotspot to be in as a queer person.” It's more like hell. This is also what we wanted to showcase.

What we did for the campaign was to stage a pool party that calls to mind the pool and beach parties that take place in Tel Aviv. In 2005 the Israeli government released a campaign called “Brand Israel” to promote the country in the LGBTQ market, using magazine covers and all kinds of advertisements to promote Tel Aviv as a gay haven. We played with that idea of a Tel Aviv pool party as an emblematic image of “Brand Israel,” using the iconic imagery of luxury excess created by Steven Meisel for Versace in the 1990s as a visual reference, and contaminating it with elements like handcuffs and molotov cocktails. The models look like they are having fun, posing, hanging out and lying on the floor, but if you look closely you see they are actually being arrested. We wanted the polished and perfect branding, landscapes, scenery, and fashion to distract the viewer, but if you observe more deeply you notice that there's something wrong and unexpected with what you're looking at.

Roberto Filippello

So this collection is a queer staging that exposes the hypocrisy of the State of Israel, which deflects attention from the occupation through its neoliberal self-branding politics.

Omar Braika

Yeah, it's definitely showing that. But at the same time we wanted to take the angle of our own lived experience as queer Palestinians. You know, Palestinian queers living in Tel Aviv or in the West Bank are not granted any privilege for being queer. We wanted to highlight Israel's false narratives.

Roberto Filippello

You mean the false narrative that Israel is welcoming toward queers, and specifically Palestinian queers, right?

Omar Braika

Yes, we wanted to say “No! This is not heaven or the hotspot to be in as a queer person.” It's more like hell. This is also what we wanted to showcase.

“We want everything to be sourced locally and produced in the Middle East: the point is to support people while building an ecosystem of Arab Palestinian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi collaborators”

Roberto Filippello

Where did you shoot the campaign?

Omar Braika

We shot it in Azraq, in Jordan. We built the set in a rented hotel with a pool. Our campaigns are all shot and directed by us. We very much enjoy producing the images, in addition to the designs, because we feel like the other half of designing is image-storytelling.

Roberto Filippello

What is your relationship with other young Palestinian fashion designers?

Shukri Lawrence

As Palestinian designers we are all very much connected. For instance, we have a WhatsApp group that we use to keep each other posted on everything that happens in Palestine, even though each of us is in a different place. It's very hard for us to connect physically, in real life, even though we're all in the same region. There are many designers from Gaza and the West Bank that we can't really see in person. Right now, for instance, I am in Jerusalem and have been trying to see a designer friend in Ramallah [West Bank] for three weeks but I haven't been able to get there due to the challenges posed by Israeli checkpoints and its permit system. It would only be a 20-minute drive if there were no checkpoints. In practice, it's really hard to see each other. However, there is a kind of a creative renaissance happening in Palestine, where all designers are connecting and supporting each other. The great thing about this fashion scene is that there's no sense of being in a competitive industry. We know we are all trying to make a better place for all of us, so it's crucial to be connected.

Roberto Filippello

You are based in Amman. Can you tell me a bit about Amman as a context for your work? I would assume that in terms of the logistics of production, things are much easier for a designer in Jordan?

Omar Braika

We produce in Amman and there are multiple reasons for this. The first one is political: choosing to have a fully Arab production, like using fabrics sourced locally, working with Arab tailors, Arab printing, etc. We want everything to be sourced locally and produced in the Middle East: the point is to support people while building an ecosystem of Arab Palestinian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi collaborators – all from different nationalities and living in Jordan. Doing that from Palestine is impossible because if you're going to get fabric locally, that's probably going to come from Israel somehow and you're inevitably going to have to work with some Israeli companies. So, we produce in Jordan to take a political stance. We do work with [Palestinian] tailors who live in Jerusalem and Ramallah as well because we have a network here, but things are just harder to navigate.

Where did you shoot the campaign?

Omar Braika

We shot it in Azraq, in Jordan. We built the set in a rented hotel with a pool. Our campaigns are all shot and directed by us. We very much enjoy producing the images, in addition to the designs, because we feel like the other half of designing is image-storytelling.

Roberto Filippello

What is your relationship with other young Palestinian fashion designers?

Shukri Lawrence

As Palestinian designers we are all very much connected. For instance, we have a WhatsApp group that we use to keep each other posted on everything that happens in Palestine, even though each of us is in a different place. It's very hard for us to connect physically, in real life, even though we're all in the same region. There are many designers from Gaza and the West Bank that we can't really see in person. Right now, for instance, I am in Jerusalem and have been trying to see a designer friend in Ramallah [West Bank] for three weeks but I haven't been able to get there due to the challenges posed by Israeli checkpoints and its permit system. It would only be a 20-minute drive if there were no checkpoints. In practice, it's really hard to see each other. However, there is a kind of a creative renaissance happening in Palestine, where all designers are connecting and supporting each other. The great thing about this fashion scene is that there's no sense of being in a competitive industry. We know we are all trying to make a better place for all of us, so it's crucial to be connected.

Roberto Filippello

You are based in Amman. Can you tell me a bit about Amman as a context for your work? I would assume that in terms of the logistics of production, things are much easier for a designer in Jordan?

Omar Braika

We produce in Amman and there are multiple reasons for this. The first one is political: choosing to have a fully Arab production, like using fabrics sourced locally, working with Arab tailors, Arab printing, etc. We want everything to be sourced locally and produced in the Middle East: the point is to support people while building an ecosystem of Arab Palestinian, Jordanian, Syrian, and Iraqi collaborators – all from different nationalities and living in Jordan. Doing that from Palestine is impossible because if you're going to get fabric locally, that's probably going to come from Israel somehow and you're inevitably going to have to work with some Israeli companies. So, we produce in Jordan to take a political stance. We do work with [Palestinian] tailors who live in Jerusalem and Ramallah as well because we have a network here, but things are just harder to navigate.

Roberto Filippello

I'd like to talk a bit about your recent (S/S 2022) collaboration with [Berlin-based BIPOC fashion collective] GmbH and your “Free Palestine” t-shirts.

Shukri Lawrence

Yes. We had been in touch with GmbH at the beginning of the year [2021] and we wanted to work on a project together. Eventually they invited us to design some shirts for their show at Paris Fashion Week. The collection was called “White Noise” and asked what it would mean to appropriate white culture and what that would look like. They wanted to include a shirt in support of Palestine and we agreed on having the proceeds from the sales distributed to two Palestinian charities: “The Land of Canaan,”which is a foundation that supports farm communities and village-based cooperatives in Palestine, and “alQaws for Gender and Sexual Diversity,” a queer activist organization. [2] We did research into our own archives – we collect all kinds of posters (political ads, posters of pop stars, etc.) and we always work with our archive when we're designing. We shared a bunch of historical and political posters with the GmbH team, then we did about fifteen designs, and finally we mixed them and produced one design where multiple posters are referenced.

Roberto Filippello

What is your relationship with [Palestinian queer activist organization] alQaws?

Omar Braika

We are not in direct contact with them, but alQaws is one of the organizations that we've always admired. We really respect the work they do for queer

Palestinians in the West Bank, in Jerusalem, and all over Palestine. They have established a framework and a language for educating others on what it means to identify as both queer and Palestinian and how it might be possible to have your needs met and achieve freedom as queers in a free Palestine. They also organize protests to show that we're here and we exist. They're all about education and that's something that we appreciate and support.

I'd like to talk a bit about your recent (S/S 2022) collaboration with [Berlin-based BIPOC fashion collective] GmbH and your “Free Palestine” t-shirts.

Shukri Lawrence

Yes. We had been in touch with GmbH at the beginning of the year [2021] and we wanted to work on a project together. Eventually they invited us to design some shirts for their show at Paris Fashion Week. The collection was called “White Noise” and asked what it would mean to appropriate white culture and what that would look like. They wanted to include a shirt in support of Palestine and we agreed on having the proceeds from the sales distributed to two Palestinian charities: “The Land of Canaan,”which is a foundation that supports farm communities and village-based cooperatives in Palestine, and “alQaws for Gender and Sexual Diversity,” a queer activist organization. [2] We did research into our own archives – we collect all kinds of posters (political ads, posters of pop stars, etc.) and we always work with our archive when we're designing. We shared a bunch of historical and political posters with the GmbH team, then we did about fifteen designs, and finally we mixed them and produced one design where multiple posters are referenced.

Roberto Filippello

What is your relationship with [Palestinian queer activist organization] alQaws?

Omar Braika

We are not in direct contact with them, but alQaws is one of the organizations that we've always admired. We really respect the work they do for queer

Palestinians in the West Bank, in Jerusalem, and all over Palestine. They have established a framework and a language for educating others on what it means to identify as both queer and Palestinian and how it might be possible to have your needs met and achieve freedom as queers in a free Palestine. They also organize protests to show that we're here and we exist. They're all about education and that's something that we appreciate and support.

Figure 5. “Miss Apartheid” look, Fall/Winter 2021 “Errorvision” collection

Figure 5. “Miss Apartheid” look, Fall/Winter 2021 “Errorvision” collection“Pinkwashing imposes the narrative that your Palestinian identity and your queer identity are in contradiction with each other.”

Figure 6. “Identity hood” jacket, Fall/Winter 2021 “Errorvision” collection

Figure 6. “Identity hood” jacket, Fall/Winter 2021 “Errorvision” collectionRoberto Filippello

They also do amazing work with academics, both Palestinians and from elsewhere, whether by giving talks and presentations at universities or collaborating on research and writing projects with scholars. Even from outside Palestine, we owe a lot to them. Thinking about this activist component of your work and your design collections, I'd like to hear about your latest [Fall/Winter 2021] collection, “Errorvision,” and in particular the boycott aspect of the collection.

Shukri Lawrence

Yes, so the “Errorvision” collection looks at the branding of competitions such as “Miss Universe,” “Eurovision,” and the Olympics. We imagined and created characters like the soldier-popstar, the soldier-sport competitor, and a Miss Universe that we call “Miss Apartheid.” It's a satirical critique of those figures who infiltrate arts and sports spaces, using art or sport to spread their political agendas. Shiny competitions like the ones I've mentioned participate [in the case of Israel] in the branding of an apartheid state. It was very obvious to us to display the collection in a filmed fashion show considering that the collection references popular shows. At the same time, we wanted the location to be somewhat of a factory, a camp, to convey the idea that these soldiers and imperial popstars are on a mission – they are on their way to “artwash” Israeli policies in Palestine. Then in the show we move from criticizing these competitions to referencing dictators like Saddam [Hussein] or [Muammar] Gaddafi to highlight how the competitions look like presidential elections with all the flags and a heavily political structure. In the collection we also wanted to draw attention to the aspect of protest. We designed the “identity hood” jacket, a faux fur piece that resembles the t-shirts that protesters typically wear but has a hood that references the Israeli practice of masking the faces of Palestinians when they arrest them. Then we put a zipper so that if you unzip it from the head, it becomes a big collar. If you keep unzipping, it takes the shape of an eagle's wings from the back: it becomes a political symbol of freedom. We introduced fake fur in this collection to symbolize the idea of partying and having competitions on stolen land – so we referenced how animal skin is used superficially and carelessly. The models in the runway show embody these oppressive ideologies which we tried to expose and mess with at the same time.

Roberto Filippello

This makes me think about how Israel claims its own identity as a Western country by hosting “Eurovision” or “Miss Universe,” either appropriating or silencing Palestinian culture. So what you were doing, and please correct me if I'm wrong, was to shed light on oppressive logics and symbolism and, through clothing, reshuffle these to affirm your narrative, your agency, and your unwillingness to succumb to these logics.

Omar Braika

Yes, exactly. This is also reflected in the casting: 99% of our casting is Palestinian models – mostly Palestinian-Jordanians – because having Palestinian models showcase our pieces is part of this idea of reclaiming and asserting our stories.

Roberto Filippello

I love how image-making is central to your design process. The Israeli occupation is very much like a visual occupation as well, so this idea of taking charge of your own representation and visibility seems like a powerful way to mess with the dominant gaze to which Palestinians are subjected as well as with this gaze's attempt to render Palestinian bodies invisible. [3] It's really powerful and can also educate other fashion practitioners on how to use their craft ingeniously to take a political stance against oppression.

Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika

Thank you.

Roberto Filippello

I'd like to hear what you think fashion can contribute to the Palestinian struggle for liberation. I know it's a huge and complex question to ask...

Shukri Lawrence

I think every Palestinian does what they are able to do to help their cause. As designers, Omar and I are making our contribution in the fashion space. We think fashion can educate, it can create conversations, can highlight stories, and can address issues that people have never even known about. For instance, for our debut collection, which we showed in Berlin in 2018, we recreated the Occupation Wall on the runway, and maybe 99% of people were shocked to even know that a wall like that existed in real life. So we are highlighting a cause within a space that usually does not want to talk about this kind of issue. We think that has power because education can be very powerful, especially when it's done through visual storytelling and fashion. When people are wearing clothes they're also carrying the story behind them on their body, and that's a very intimate thing.

Roberto Filippello

Queerness is at the core of your brand's philosophy and aesthetic. How do the anti-occupation movement and the queer struggle interconnect in Palestine?

Omar Braika

They go hand in hand because you can't have free queer Palestinians without a free Palestine. In order to achieve that you need to plant the seeds for it. That's why we do what we do through representation as a way to fight for queer freedom. In order to be able to live in a free Palestine, queer people need to be able to have rights. Right now, queer Palestinians are facing the very harmful effects of pinkwashing: essentially, two main facets of our identity, Palestinian and queer, are used [by Israeli discourse and representation] against each other. Pinkwashing imposes the narrative that your Palestinian identity and your queer identity are in contradiction with each other. This false narrative is oppressive towards us and our people and it has the effect of creating more internal violence.

Roberto Filippello

I think the “pinkwatching” angle you're embracing through strategies such as satirical branding can be really powerful, because it's something that can be understood by a larger audience or at least it can shake people up and encourage them to learn [4] I appreciate how much you care about your work being educational: it can push people to familiarize themselves with what's going on without falling victim to the discourse of a conflict that is “too complex” or thorny to understand. By raising awareness about the queer Palestinian struggle, we might begin to notice how the Palestinian plight connects with so many other communities' struggles. Hopefully fashion can offer, especially for young people, a platform for having these conversations.

Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika

We hope so too!

Notes: Queer Fashion Against Pinkwashing

[1] Schulman, Sarah. 2011. “Israel and ‘Pinkwashing.”’ New York Times, November 22. Available at: nytimes.com/2011/11/23/opinion/pinkwashing-and-israels-use-of-gays-as-a-messaging-tool.html

[2] landofcanaanfoundation.org/ ; alqaws.org/siteEn/index

[3] Gil H. Hochberg, Visual Occupations: Violence and Visibility in a Conflict Zone (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

[4] pinkwatchingisrael.com/

They also do amazing work with academics, both Palestinians and from elsewhere, whether by giving talks and presentations at universities or collaborating on research and writing projects with scholars. Even from outside Palestine, we owe a lot to them. Thinking about this activist component of your work and your design collections, I'd like to hear about your latest [Fall/Winter 2021] collection, “Errorvision,” and in particular the boycott aspect of the collection.

Shukri Lawrence

Yes, so the “Errorvision” collection looks at the branding of competitions such as “Miss Universe,” “Eurovision,” and the Olympics. We imagined and created characters like the soldier-popstar, the soldier-sport competitor, and a Miss Universe that we call “Miss Apartheid.” It's a satirical critique of those figures who infiltrate arts and sports spaces, using art or sport to spread their political agendas. Shiny competitions like the ones I've mentioned participate [in the case of Israel] in the branding of an apartheid state. It was very obvious to us to display the collection in a filmed fashion show considering that the collection references popular shows. At the same time, we wanted the location to be somewhat of a factory, a camp, to convey the idea that these soldiers and imperial popstars are on a mission – they are on their way to “artwash” Israeli policies in Palestine. Then in the show we move from criticizing these competitions to referencing dictators like Saddam [Hussein] or [Muammar] Gaddafi to highlight how the competitions look like presidential elections with all the flags and a heavily political structure. In the collection we also wanted to draw attention to the aspect of protest. We designed the “identity hood” jacket, a faux fur piece that resembles the t-shirts that protesters typically wear but has a hood that references the Israeli practice of masking the faces of Palestinians when they arrest them. Then we put a zipper so that if you unzip it from the head, it becomes a big collar. If you keep unzipping, it takes the shape of an eagle's wings from the back: it becomes a political symbol of freedom. We introduced fake fur in this collection to symbolize the idea of partying and having competitions on stolen land – so we referenced how animal skin is used superficially and carelessly. The models in the runway show embody these oppressive ideologies which we tried to expose and mess with at the same time.

Roberto Filippello

This makes me think about how Israel claims its own identity as a Western country by hosting “Eurovision” or “Miss Universe,” either appropriating or silencing Palestinian culture. So what you were doing, and please correct me if I'm wrong, was to shed light on oppressive logics and symbolism and, through clothing, reshuffle these to affirm your narrative, your agency, and your unwillingness to succumb to these logics.

Omar Braika

Yes, exactly. This is also reflected in the casting: 99% of our casting is Palestinian models – mostly Palestinian-Jordanians – because having Palestinian models showcase our pieces is part of this idea of reclaiming and asserting our stories.

Roberto Filippello

I love how image-making is central to your design process. The Israeli occupation is very much like a visual occupation as well, so this idea of taking charge of your own representation and visibility seems like a powerful way to mess with the dominant gaze to which Palestinians are subjected as well as with this gaze's attempt to render Palestinian bodies invisible. [3] It's really powerful and can also educate other fashion practitioners on how to use their craft ingeniously to take a political stance against oppression.

Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika

Thank you.

Roberto Filippello

I'd like to hear what you think fashion can contribute to the Palestinian struggle for liberation. I know it's a huge and complex question to ask...

Shukri Lawrence

I think every Palestinian does what they are able to do to help their cause. As designers, Omar and I are making our contribution in the fashion space. We think fashion can educate, it can create conversations, can highlight stories, and can address issues that people have never even known about. For instance, for our debut collection, which we showed in Berlin in 2018, we recreated the Occupation Wall on the runway, and maybe 99% of people were shocked to even know that a wall like that existed in real life. So we are highlighting a cause within a space that usually does not want to talk about this kind of issue. We think that has power because education can be very powerful, especially when it's done through visual storytelling and fashion. When people are wearing clothes they're also carrying the story behind them on their body, and that's a very intimate thing.

Roberto Filippello

Queerness is at the core of your brand's philosophy and aesthetic. How do the anti-occupation movement and the queer struggle interconnect in Palestine?

Omar Braika

They go hand in hand because you can't have free queer Palestinians without a free Palestine. In order to achieve that you need to plant the seeds for it. That's why we do what we do through representation as a way to fight for queer freedom. In order to be able to live in a free Palestine, queer people need to be able to have rights. Right now, queer Palestinians are facing the very harmful effects of pinkwashing: essentially, two main facets of our identity, Palestinian and queer, are used [by Israeli discourse and representation] against each other. Pinkwashing imposes the narrative that your Palestinian identity and your queer identity are in contradiction with each other. This false narrative is oppressive towards us and our people and it has the effect of creating more internal violence.

Roberto Filippello

I think the “pinkwatching” angle you're embracing through strategies such as satirical branding can be really powerful, because it's something that can be understood by a larger audience or at least it can shake people up and encourage them to learn [4] I appreciate how much you care about your work being educational: it can push people to familiarize themselves with what's going on without falling victim to the discourse of a conflict that is “too complex” or thorny to understand. By raising awareness about the queer Palestinian struggle, we might begin to notice how the Palestinian plight connects with so many other communities' struggles. Hopefully fashion can offer, especially for young people, a platform for having these conversations.

Shukri Lawrence and Omar Braika

We hope so too!

Notes: Queer Fashion Against Pinkwashing

[1] Schulman, Sarah. 2011. “Israel and ‘Pinkwashing.”’ New York Times, November 22. Available at: nytimes.com/2011/11/23/opinion/pinkwashing-and-israels-use-of-gays-as-a-messaging-tool.html

[2] landofcanaanfoundation.org/ ; alqaws.org/siteEn/index

[3] Gil H. Hochberg, Visual Occupations: Violence and Visibility in a Conflict Zone (Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

[4] pinkwatchingisrael.com/

By Hennessy Eileen

Due to the political situation in Hong Kong as of the time of writing (March 2022), the author of this article (”Hennessy Eileen”) decided not to be published to avoid putting her personal safety at risk.

The Border Creatures leave this page obscured in honor of authors whose voices have been silenced by the circumstances in which they live (or survive).

****** **** ***** *********** ***** ********* *** * *** *** ****, **** *** *****, ***** ****** ***** *** ****** *** *********. ***** ******* ******* *********** ** ********* **** ******. ** ******** ****** *** ** *** ****** ********* ********* ** **** **** (***** ****), *** ****** ** **** ******* (******** ******) ******* *** ** ** ********* ** ***** ******* *** ******** ****** ** ****. *** ****** ********* ***** **** **** ***** ** ***** ** ******* ****** ****** **** **** ******** ** *** ************* ** ***** **** **** (** *******).

* ******* **** **** **** **** *********. * ***’* **** **** **** ** ********. *** **** ****** **** **** ***? **’** *** ****** **** *** *****. ****** * ** **** ** ******* ** ** ********? ** *** ** ******* **** * *** ************ ***** ** ******** *** ******* ****** ****** ****** **’* ***** ** ** ***** *** ** **? *’* *** **** ****** **** ********, **** *** ********** ***** * ******** ********* **** *** ***** ****** ***** ********* *’* ******* **** ******** ** **** ********** ****** ** *** **** ********.

*** ***** ********* ** ***** ** *** ***** ***** **** *** * ***’* **** ********** ****** **. * ******* ******** *** ***** **** *** **** **** ******** * ****. *** ****** **** *********. ** **** ***** *******, **’* **** *** ** ****** ******* ** ** ***. ** * ***’*. ***** ** **** *** (***** **** **** ****). **’* *** *** ******** ***** ***********. ** *** *********** *** ******? * ***** ** ***** ** **** ***** *** * ***** ***’* **** * ***. ***** *** *** ***** ****** **** *** ** ***’* **** *’** *** *** ** ****. **** ** * *** ** ** ******.***?

**, *’** ** *** *** ******** ** ******. ********* *** *** ** *** *** ********* ** *** *********** *** *** **** ***** ******** ************* **********. *** **** *** **** ** **** **** **** **** ***** ***? ** ***** ***** ***, ** * ***** ** *** ******** ****. *** **** *** **** **? *** ***** ***** ****. *** **** ** **** ** **** ****. **** *** **** **** ***, *** * ***** **** ***** ******* ** ** **** ******’ ******. ** ***** ** **** *** *** **** ****-***** ******** **** ********* ** ***** ****, ** ****** ****’* ***** ** ***** ****** ******* ** *** ***** *** **** ** **** *** **** ***. * **** * ******** ***** ****** **** ***** ** ****.

* ******* **** **** **** **** *********. * ***’* **** **** **** ** ********. *** **** ****** **** **** ***? **’** *** ****** **** *** *****. ****** * ** **** ** ******* ** ** ********? ** *** ** ******* **** * *** ************ ***** ** ******** *** ******* ****** ****** ****** **’* ***** ** ** ***** *** ** **? *’* *** **** ****** **** ********, **** *** ********** ***** * ******** ********* **** *** ***** ****** ***** ********* *’* ******* **** ******** ** **** ********** ****** ** *** **** ********.

*** ***** ********* ********* * ******’* ************ **** ** *** **** ** ******** ** * ****** ***** *** ***** *****, ***** ** *** ***** *** * *****-**** ****, **** ** ******** ********* *****, ******* ****** ******* *****, *** ******* *******. *****, ****** ******* ***** ***** **** **** ** ******* * ***** *****. ** **** ***’* **, **’* ******** *******. *** ***** ********. ** **** *** ****** ***** ******** ********* *** ******** ******** ******. **** ** ** **** *** *****, **** * **** **** **** **** ********* ***** ** *** ***** *****! * **** **** *** ***** ***** ********, *** ** * ***** ******* ***, ****.

*** ***** ********* ** ***** ** *** ***** ***** **** *** * ***’* **** ********** ****** **. * ******* ******** *** ***** **** *** **** **** ******** * ****. *** ****** **** *********. ** **** ***** *******, **’* **** *** ** ****** ******* ** ** ***. ** * ***’*. ***** ** **** *** (***** **** **** ****). **’* *** *** ******** ***** ***********. ** *** *********** *** ******? * ***** ** ***** ** **** ***** *** * ***** ***’* **** * ***. ***** *** *** ***** ****** **** *** ** ***’* **** *’** *** *** ** ****. **** ** * *** ** ** ******.***?

***** * **** ** ** **** ********* **** * **** ***** *** **** *** ****. * **** ** **** *** ** *** *** *****. * **** ** ******* ** ******, ******, *****, *** ***** ***** ********* * **** **** **** *** ***** **** **** *** **** ***** ***** ******* *** **. * **** ** ****** *** *** ****** *** *****. * **** ** ******* *** ****. * **** ** ******* *** *** ** ****** * **** *** ** *****. ***, ** ********, * **** ** ***** -- ** ** ****** *** ******* ** ** ********** -- *** *** ******** ******* ***. **’* * *** * **** * *** **, *** * **** *** ***** *** ** **** *******. ******* **** **** ******** ** *** **** ********* ** ******* *** *********. * ** ** ********. **** **** ****** *** *** ******** ******* * *********, *** * **** **** ******* * **** ********. *** * **** **** **** **** ******** ** **!

*** ***** ********* ********* * ******’* ************ **** ** *** **** ** ******** ** * ****** ***** *** ***** *****, ***** ** *** ***** *** * *****-**** ****, **** ** ******** ********* *****, ******* ****** ******* *****, *** ******* *******. *****, ****** ******* ***** ***** **** **** ** ******* * ***** *****. ** **** ***’* **, **’* ******** *******. *** ***** ********. ** **** *** ****** ***** ******** ********* *** ******** ******** ******. **** ** ** **** *** *****, **** * **** **** **** **** ********* ***** ** *** ***** *****! * **** **** *** ***** ***** ********, *** ** * ***** ******* ***, ****.

*** ***** **, “** *** **** **** **** * ******** ***?” ** * ****’* **** **** ** ***. * **** **** ******* * * * ***** **** ***. * **** ****** *** ** ******* **** * ***** **** **** *** **** ***. * **** *’* *** ****’* **** (***** **.). **** ** ** ****** **** *** ***. ***** * ****** ******* * ******** ** ‘****’ ** ****** ****** *** ****** *** ******. *****’* *** **** ***** “******* ** *** ***** **** * ****** ****.’ *** * **** ** **** **** *** ***** ***** *** ******** ** * **** ** ***** ********* *** **** ***** ******** *** * *** ******** ** ** **** *********. ***** ** ***** ***, *** * *** **** ** ** * ****** ****-*********. * **** **** ****** ** ******* **** *** **** ********? ******.

* ******* **** **** **** **** *********. * ***’* **** **** **** ** ********. *** **** ****** **** **** ***? **’** *** ****** **** *** *****. ****** * ** **** ** ******* ** ** ********? ** *** ** ******* **** * *** ************ ***** ** ******** *** ******* ****** ****** ****** **’* ***** ** ** ***** *** ** **? *’* *** **** ****** **** ********, **** *** ********** ***** * ******** ********* **** *** ***** ****** ***** ********* *’* ******* **** ******** ** **** ********** ****** ** *** **** ********.

*** ***** ********* ** ***** ** *** ***** ***** **** *** * ***’* **** ********** ****** **. * ******* ******** *** ***** **** *** **** **** ******** * ****. *** ****** **** *********. ** **** ***** *******, **’* **** *** ** ****** ******* ** ** ***. ** * ***’*. ***** ** **** *** (***** **** **** ****). **’* *** *** ******** ***** ***********. ** *** *********** *** ******? * ***** ** ***** ** **** ***** *** * ***** ***’* **** * ***. ***** *** *** ***** ****** **** *** ** ***’* **** *’** *** *** ** ****. **** ** * *** ** ** ******.***?

**, *’** ** *** *** ******** ** ******. ********* *** *** ** *** *** ********* ** *** *********** *** *** **** ***** ******** ************* **********. *** **** *** **** ** **** **** **** **** ***** ***? ** ***** ***** ***, ** * ***** ** *** ******** ****. *** **** *** **** **? *** ***** ***** ****. *** **** ** **** ** **** ****. **** *** **** **** ***, *** * ***** **** ***** ******* ** ** **** ******’ ******. ** ***** ** **** *** *** **** ****-***** ******** **** ********* ** ***** ****, ** ****** ****’* ***** ** ***** ****** ******* ** *** ***** *** **** ** **** *** **** ***. * **** * ******** ***** ****** **** ***** ** ****.

* ******* **** **** **** **** *********. * ***’* **** **** **** ** ********. *** **** ****** **** **** ***? **’** *** ****** **** *** *****. ****** * ** **** ** ******* ** ** ********? ** *** ** ******* **** * *** ************ ***** ** ******** *** ******* ****** ****** ****** **’* ***** ** ** ***** *** ** **? *’* *** **** ****** **** ********, **** *** ********** ***** * ******** ********* **** *** ***** ****** ***** ********* *’* ******* **** ******** ** **** ********** ****** ** *** **** ********.

*** ***** ********* ********* * ******’* ************ **** ** *** **** ** ******** ** * ****** ***** *** ***** *****, ***** ** *** ***** *** * *****-**** ****, **** ** ******** ********* *****, ******* ****** ******* *****, *** ******* *******. *****, ****** ******* ***** ***** **** **** ** ******* * ***** *****. ** **** ***’* **, **’* ******** *******. *** ***** ********. ** **** *** ****** ***** ******** ********* *** ******** ******** ******. **** ** ** **** *** *****, **** * **** **** **** **** ********* ***** ** *** ***** *****! * **** **** *** ***** ***** ********, *** ** * ***** ******* ***, ****.

*** ***** ********* ** ***** ** *** ***** ***** **** *** * ***’* **** ********** ****** **. * ******* ******** *** ***** **** *** **** **** ******** * ****. *** ****** **** *********. ** **** ***** *******, **’* **** *** ** ****** ******* ** ** ***. ** * ***’*. ***** ** **** *** (***** **** **** ****). **’* *** *** ******** ***** ***********. ** *** *********** *** ******? * ***** ** ***** ** **** ***** *** * ***** ***’* **** * ***. ***** *** *** ***** ****** **** *** ** ***’* **** *’** *** *** ** ****. **** ** * *** ** ** ******.***?

***** * **** ** ** **** ********* **** * **** ***** *** **** *** ****. * **** ** **** *** ** *** *** *****. * **** ** ******* ** ******, ******, *****, *** ***** ***** ********* * **** **** **** *** ***** **** **** *** **** ***** ***** ******* *** **. * **** ** ****** *** *** ****** *** *****. * **** ** ******* *** ****. * **** ** ******* *** *** ** ****** * **** *** ** *****. ***, ** ********, * **** ** ***** -- ** ** ****** *** ******* ** ** ********** -- *** *** ******** ******* ***. **’* * *** * **** * *** **, *** * **** *** ***** *** ** **** *******. ******* **** **** ******** ** *** **** ********* ** ******* *** *********. * ** ** ********. **** **** ****** *** *** ******** ******* * *********, *** * **** **** ******* * **** ********. *** * **** **** **** **** ******** ** **!

*** ***** ********* ********* * ******’* ************ **** ** *** **** ** ******** ** * ****** ***** *** ***** *****, ***** ** *** ***** *** * *****-**** ****, **** ** ******** ********* *****, ******* ****** ******* *****, *** ******* *******. *****, ****** ******* ***** ***** **** **** ** ******* * ***** *****. ** **** ***’* **, **’* ******** *******. *** ***** ********. ** **** *** ****** ***** ******** ********* *** ******** ******** ******. **** ** ** **** *** *****, **** * **** **** **** **** ********* ***** ** *** ***** *****! * **** **** *** ***** ***** ********, *** ** * ***** ******* ***, ****.

*** ***** **, “** *** **** **** **** * ******** ***?” ** * ****’* **** **** ** ***. * **** **** ******* * * * ***** **** ***. * **** ****** *** ** ******* **** * ***** **** **** *** **** ***. * **** *’* *** ****’* **** (***** **.). **** ** ** ****** **** *** ***. ***** * ****** ******* * ******** ** ‘****’ ** ****** ****** *** ****** *** ******. *****’* *** **** ***** “******* ** *** ***** **** * ****** ****.’ *** * **** ** **** **** *** ***** ***** *** ******** ** * **** ** ***** ********* *** **** ***** ******** *** * *** ******** ** ** **** *********. ***** ** ***** ***, *** * *** **** ** ** * ****** ****-*********. * **** **** ****** ** ******* **** *** **** ********? ******.

by Lucia Cuba

Versión en castellano aquí

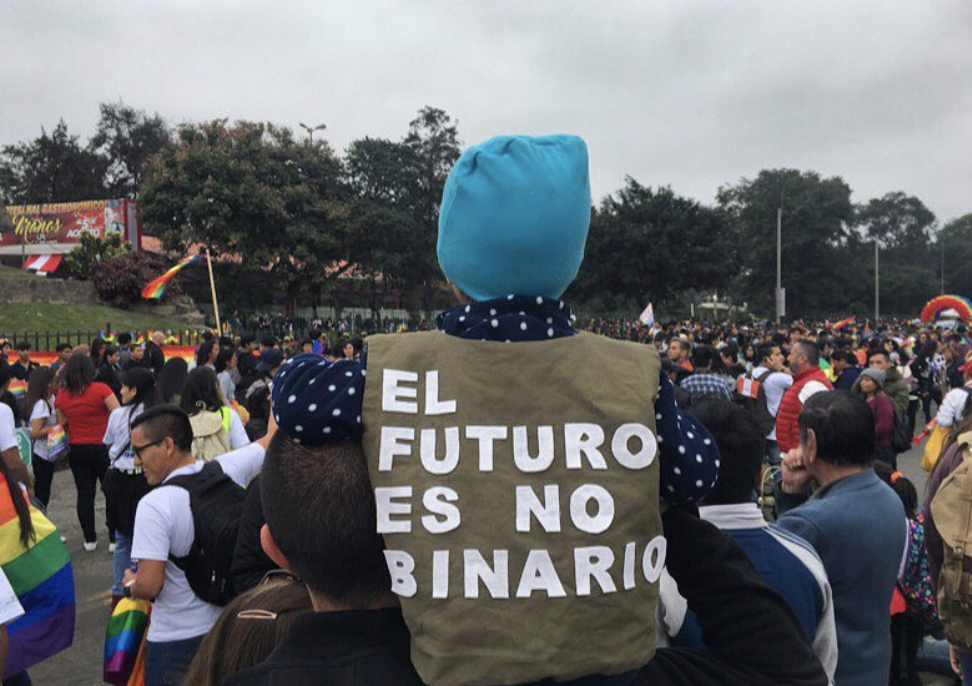

Figure 1. Lima, July 1, 2018. “The Future is non-Binary.” LBGT Pride March.

Figure 1. Lima, July 1, 2018. “The Future is non-Binary.” LBGT Pride March.

Lucia Cuba approaches fashion, textiles, and the exploration of wearable forms as performative and political devices. As a fashion designer and a scholar, Cuba is interested in issues of gender, biopolitics, and global fashion practices. She has developed projects related to health, activism, education, and the study of non-Western fashion systems. She currently works as an independent designer, as the Director of the MFA Fashion Design and Society, and Professor of Fashion Design and Social Justice, at The New School University. [luciacuba.com].

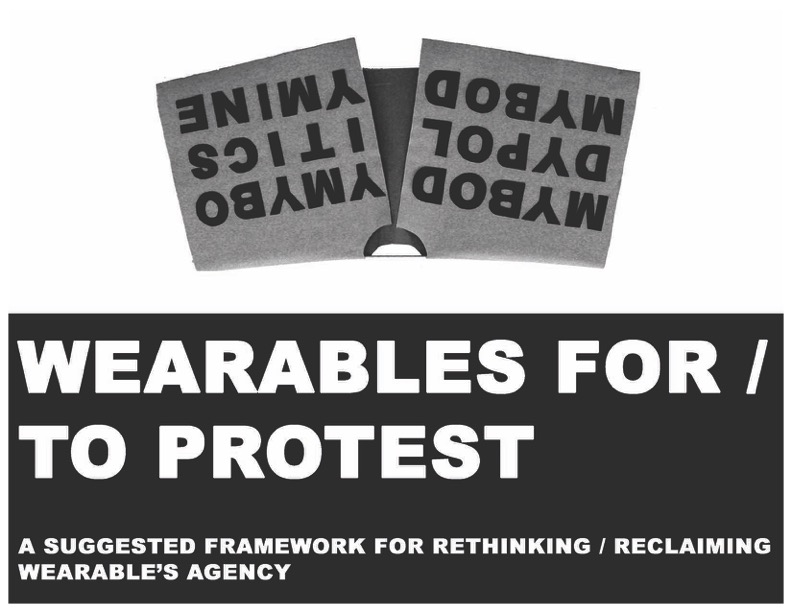

Can wearable objects spark critical conversations? Can textile resources (such as fabrics, sewing techniques, or clothing patterns) be appropriated by all, and not just those who are professionally involved with fashion design? Beyond public space, what other contexts can objects designed for protest occupy?

These were some of the questions that prompted the development of the project “Wearables for/to protest” (WFTP), an exercise of construction and representation of personal and social events transformed into functional and wearable objects. The project is activated through wearable textile creations, on the body of those who wear them, and through workshops where participants engage in multiple processes related to the construction of these objects, as well as conversations about social and personal issues.

Conceived as political devices, these wearable objects record acts of individual protest against ideas and institutions and in turn, serve as tools to generate a reaction from those who confront them.[1] This series proposes that political creation and mobilization can take place in daily life, through individual acts, and in dialogue with what one wants to transform or actively resist.

WFTP originated at the end of 2016, in the context of the presidential elections in the United States. That year, the potential election of Donald J. Trump sparked multiple conversations about sexual and reproductive rights and the right to abortion among United States citizens. This was a period marked by activism and popular protests that triggered conversations about social justice and citizen participation in defining a public agenda.

These were some of the questions that prompted the development of the project “Wearables for/to protest” (WFTP), an exercise of construction and representation of personal and social events transformed into functional and wearable objects. The project is activated through wearable textile creations, on the body of those who wear them, and through workshops where participants engage in multiple processes related to the construction of these objects, as well as conversations about social and personal issues.

Conceived as political devices, these wearable objects record acts of individual protest against ideas and institutions and in turn, serve as tools to generate a reaction from those who confront them.[1] This series proposes that political creation and mobilization can take place in daily life, through individual acts, and in dialogue with what one wants to transform or actively resist.

WFTP originated at the end of 2016, in the context of the presidential elections in the United States. That year, the potential election of Donald J. Trump sparked multiple conversations about sexual and reproductive rights and the right to abortion among United States citizens. This was a period marked by activism and popular protests that triggered conversations about social justice and citizen participation in defining a public agenda.

Figure 2. March 24, 2018. Archive documentation, heading to the “March for our Lives,” in New York City.

Figure 2. March 24, 2018. Archive documentation, heading to the “March for our Lives,” in New York City.During this time, the use of expressive resources that could be seen as forms for protest, such as paper or cardboard posters, began to appear not only in public spaces, but also in private spaces (houses, educational centers, and various institutions).[2] Expressive resources are, as Scribano mentions, textual objects that allow the definition, construction, and social distribution of the meaning of an action. In this context, the expressive resources went beyond the traditional forms of protest, and expanded new meanings and impacts of protesting. A good example is the “pussy hat,” a pink-knitted hat that was worn by most participants of the massive Women’s March that took place on January 21, 2017 — President Donald Trump's first full day in office — in which more than 500,000 people gathered to advocate for gender equality. The “pussy hat” became much more than a hat. For months to come, the hat would stand as a symbol of advocacy for women’s rights in the United States. It also became recognized as the result of an open-source system where participants would learn how to knit, sew and make a “pussy hat” by downloading patterns, participating in forums and learning from tutorials. The goal was for participants to make these hats to wear during the march or to send them to the organizers to distribute to those participating.

WFTP proposes a strategy for the generation of expressive resources, but with the intention of situating itself beyond an idea of fashion for protest, which Thurman defines as “a show of solidarity towards a social cause.”[3] From a critical perspective, WFTP conceives of the wearable resource as a political device that is activated not only in public space but also in private spaces (home, school, or workplace) and that acquires meaning and greater symbolic and personal value by being created by those who aim to use it.

The appropriation of creative processes (the actual creation and production of the object) that WFTP proposes through an activation workshop allows people to recognize their agency not only in the process of developing expressive resources but also in the understanding and definition of a social issue that they want to address, approaching this through the critical and physical making of the message that appears in the object. WFTP provides the opportunity for people to approach textiles as a critical medium and tool, without necessarily having advanced technical knowledge (textile appropriation resources and techniques such as sewing, weaving, embroidery, printing, etc.). [4]

First Activations

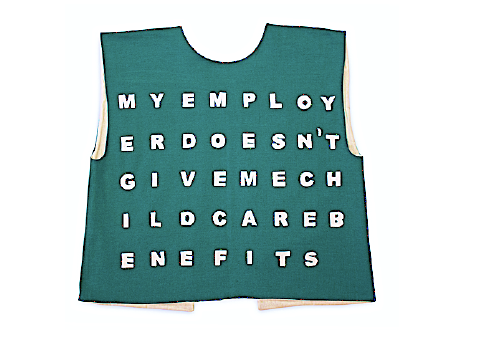

Between 2016 and 2018, two ways of approaching the project emerged. In the first approach, I developed wearables from my personal experience in relation to issues such as migration, motherhood, and work environment (See figures 3 and 4). This process took place during an artist residency at the Museum of Arts and Design, BRIC Arts Media Center, and the Center for Textile Arts in New York.

WFTP proposes a strategy for the generation of expressive resources, but with the intention of situating itself beyond an idea of fashion for protest, which Thurman defines as “a show of solidarity towards a social cause.”[3] From a critical perspective, WFTP conceives of the wearable resource as a political device that is activated not only in public space but also in private spaces (home, school, or workplace) and that acquires meaning and greater symbolic and personal value by being created by those who aim to use it.

The appropriation of creative processes (the actual creation and production of the object) that WFTP proposes through an activation workshop allows people to recognize their agency not only in the process of developing expressive resources but also in the understanding and definition of a social issue that they want to address, approaching this through the critical and physical making of the message that appears in the object. WFTP provides the opportunity for people to approach textiles as a critical medium and tool, without necessarily having advanced technical knowledge (textile appropriation resources and techniques such as sewing, weaving, embroidery, printing, etc.). [4]

First Activations

Between 2016 and 2018, two ways of approaching the project emerged. In the first approach, I developed wearables from my personal experience in relation to issues such as migration, motherhood, and work environment (See figures 3 and 4). This process took place during an artist residency at the Museum of Arts and Design, BRIC Arts Media Center, and the Center for Textile Arts in New York.

Figure 3. My employer doesn't give me childcare benefits, 2016. Open tunic in cotton, with letters in 100% wool felt.

Figure 4. I abortion, 2017. Open tunic. Textiles: neoprene, wool felt, cotton. Technique: sewing, stencil.

“Conceived as political devices, these wearable objects record acts of individual protest against ideas and institutions and in turn, serve as tools to generate a reaction from those who confront them.”

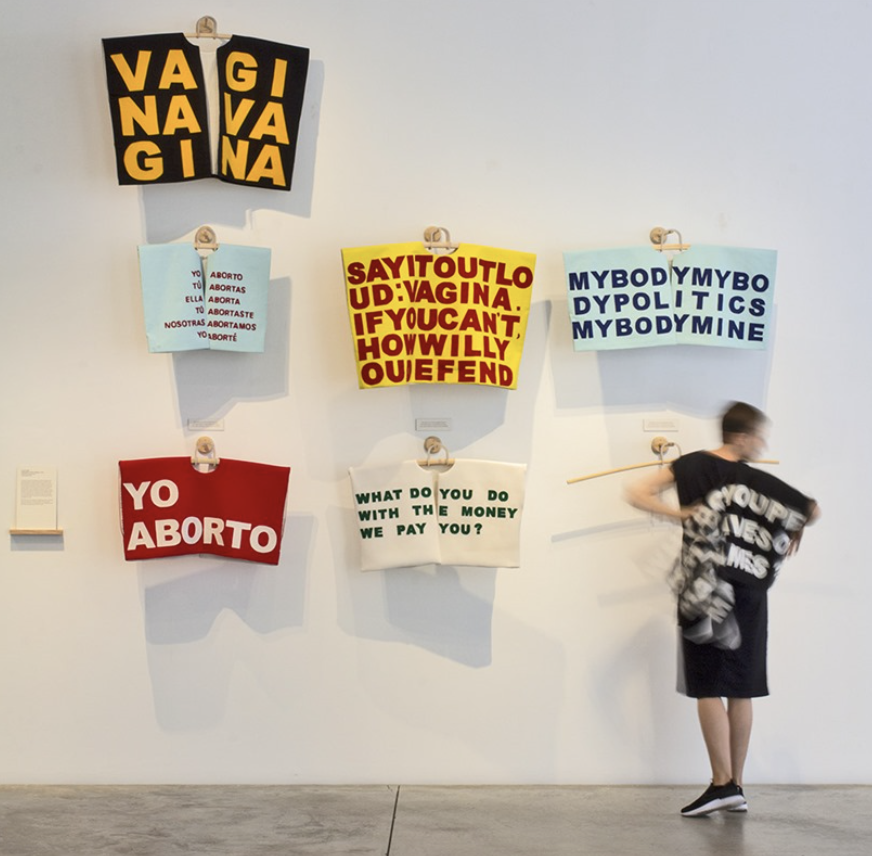

As a second approach, wearables were developed as part of workshops, where the facilitation of wearable-making processes allowed for participants to reflect upon personal and social issues they had experienced. These sessions took place at the Textile Arts Center and at Pioneer Works, two cultural spaces in New York. Later, in 2018 and 2019, two additional workshops were held as part of the Disobedient Fashion gathering organized by the Chilean collective Malvestidas (Poorly Dressed), in The Santiago Museum of Contemporary Art, and in the context of the exhibition “In the Historical Present” at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery - Sheila C. Johnson Design Center in New York.

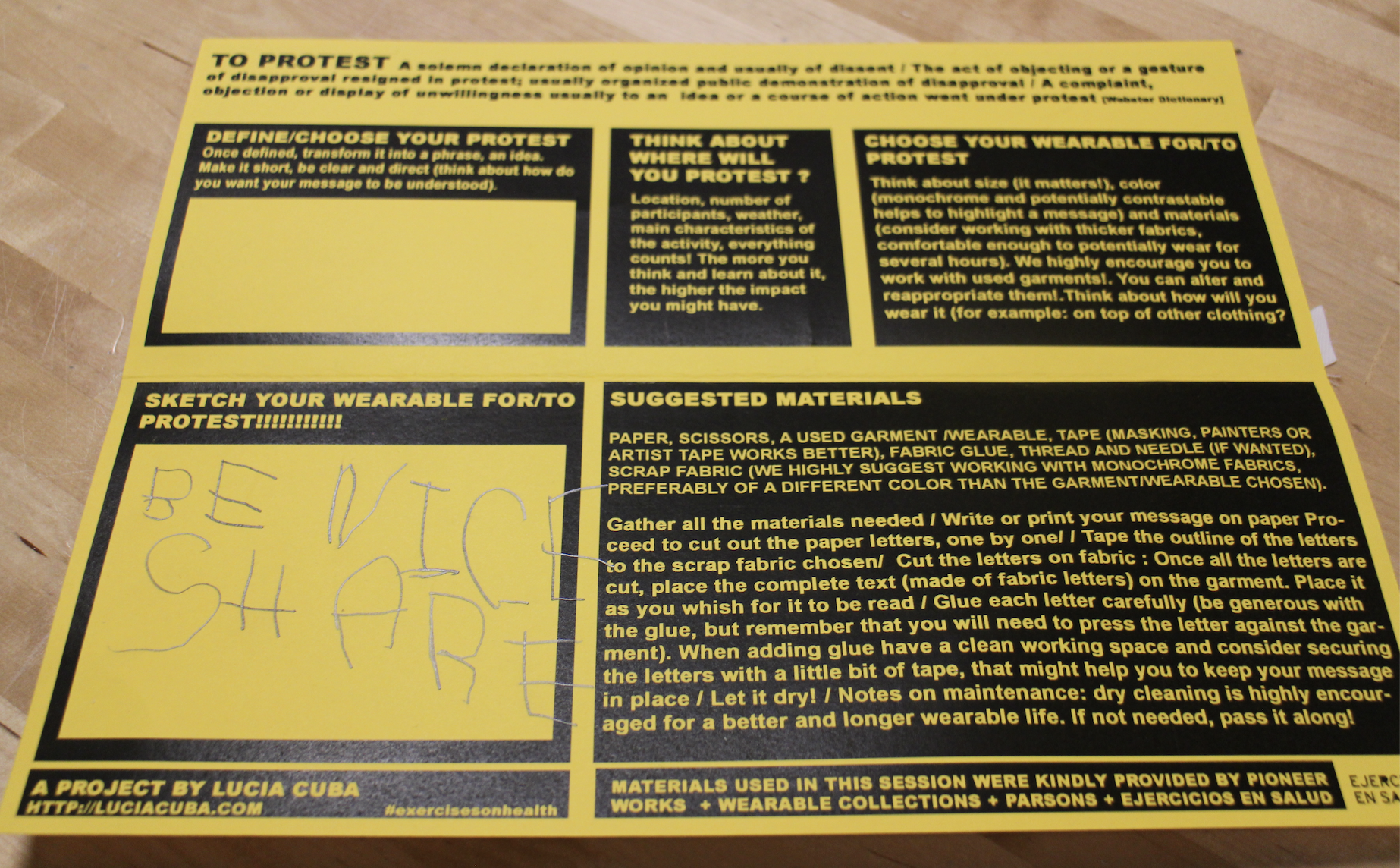

The session at Pioneer Works was open to a mixed-age audience, which allowed for a broader conversation. For example, figure 5 shows a wearable (a piece of clothing with cut-off sleeves) that reads “Puppy.” This was the result of a conversation about wearables as a means of conveying an opinion. The creator of the wearable, self-identified as a 6-year-old girl, mentioned that she wanted to adopt a dog but that this was a difficult conversation at home. Therefore, she decided to highlight the word Puppy on her garment to “make her parents think about it.” In this case, the expressive resource allows the participant to activate a personal conversation around a desire, a demand that requires a conversation with her family. On the other hand, figure 6 shows a printed guide to make a wearable for/to protest. The image shows a text written by a 7-year-old participant who chose the phrase “be nice share” to place on a wearable so that people could read it and, as mentioned by the participant, “be more friendly and supportive.”

The session at Pioneer Works was open to a mixed-age audience, which allowed for a broader conversation. For example, figure 5 shows a wearable (a piece of clothing with cut-off sleeves) that reads “Puppy.” This was the result of a conversation about wearables as a means of conveying an opinion. The creator of the wearable, self-identified as a 6-year-old girl, mentioned that she wanted to adopt a dog but that this was a difficult conversation at home. Therefore, she decided to highlight the word Puppy on her garment to “make her parents think about it.” In this case, the expressive resource allows the participant to activate a personal conversation around a desire, a demand that requires a conversation with her family. On the other hand, figure 6 shows a printed guide to make a wearable for/to protest. The image shows a text written by a 7-year-old participant who chose the phrase “be nice share” to place on a wearable so that people could read it and, as mentioned by the participant, “be more friendly and supportive.”

Figure 5 and 6. November 13, 2017. Archive documentation of the “Vestibles para/por la protesta” workshop as part of the “Fact Crafts / Family Sundays” series at the Pioneer Works cultural center in New York City.

Figure 7 and 8. The two images below belong to other wearables developed by workshop participants, both of which activate phrases linked to the “Me too” social movement, which consisted of multiple conversations and accusations about systemic sexual abuse of women. November 13, 2017. Archive documentation of the “Vestibles para/por la protesta” workshop as part of the “Fact Crafts/Family Sundays” series at the Pioneer Works cultural center in New York City.

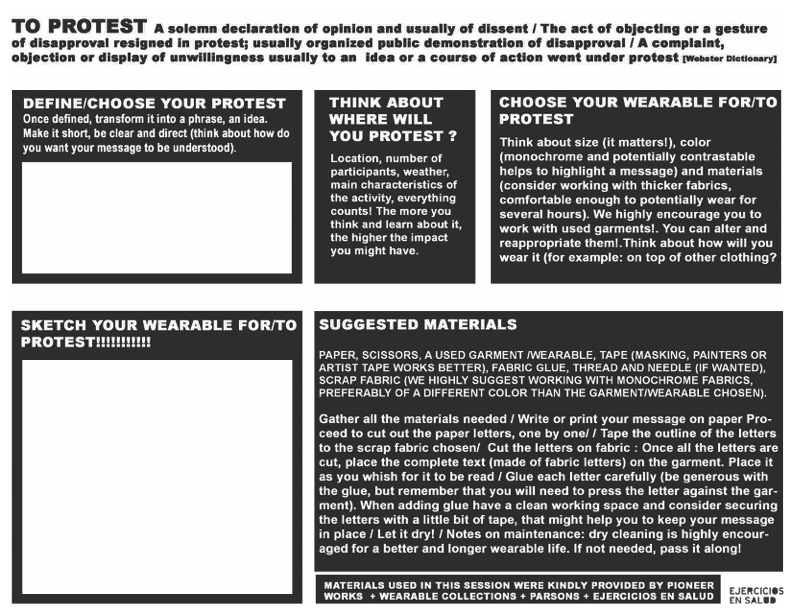

The printed guides were conceived as educational tools to facilitate the process of creating these expressive resources. Initially aimed at adults and readers, they are currently being rethought to target non-readers of various ages.

The aim of these educational resources is to teach basic stencil techniques (a technique for stamping figures), appliqué (applying cuts from one material to another), and typographic techniques (such as contrasting colors and sizes). In addition, key questions are included to guide reflection on the theme that is to be represented in the wearable. Workshop activations adapt to different contexts, including where the session is held, what infrastructure is in place, and what materials are available.

Figure 11. July - October 2019. WFTP installed as part of the exhibition “In the Historical Present” at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery-Sheila C. Johnson Design Center in New York. Wearables installed to be activated (dressed) by sample participants.