TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Letter from the Editors

By The MAFS guest editor team

- What Makes a Fashion Scholar? Disciplinary Identity and Methodological Purity in Fashion Studies By Julie Gork and Alla Eizenberg

- Fashion Sustainability, Then and Now: A 15-Year Conversation

By Sara Idacavage and Lauren Downing Peters

-

Thinking Through Fashion Practically

By Aude Fellay

- Ruth E. Carter’s Sankofa Approach to Costume Design: Gratitude for 15 Years of Afro-Historicism and Afro-Futurism in Fashion and Film

By Cydni Robertson

- Reflect Reflected Reflection

By Ines Simoes and Nuno Nogueira

- Reclaiming Sartorial Narratives Beyond Colonial Frameworks

By Sarah Javaid and Sayed Meher Ali

- The Eyes of Animals: Mirror Embroidery’s Narrative Threads

By Claire Sigal

- Unwearable “White Shirt”: An Auto-Critique of Critical Fashion with Walter Benjamin

By Muyo Park - Sustainable By Design: The Role of Indigenous Craft in Shaping a Resilient Future

By Muhammad Umer Rehman

- Fast Tatreez: Machine-Embroidered Palestinian Dresses and Reflections on the Ethics of Fashion in Exile

By Wafa Ghnaim

- Art After the Revolution: Haitian Legacies in Contemporary Practice

By Siobhan Meï and Jonathan Michael Square

Hello FSJ readers!

2025 marks the 15-year anniversary of the MA Fashion Studies Program at Parsons School of Design. For 15 years, students and faculty have lent their voices to fashion studies research and ridden the wave of the cultural evolutions that have transpired in this burgeoning field of study. Traditionally, crystal is used to acknowledge 15-year anniversaries, and just as a crystal reflects a kaleidoscope of colors and evokes a myriad of possibilities, we sought to illuminate the works of those who continue to shape this field through a special issue of the Fashion Studies Journal, entitled “Reflections.”

We invited scholars and creatives to reflect on the field of fashion studies from a multifaceted approach, embracing crystalline qualities in their works. As we might have anticipated, authors spotlighted multiple facets of the field resulting in an issue that spans the globe and decades. Authors shared about developments in the fashion industry and how the field has evolved. Alumni reflected on the evolution of their work since attending The New School and presented their ongoing work on the subject. The legacy of a costume designer is highlighted and the evolution of indigenous crafts is reflected upon.

Over the course of 15 years, trends have come and gone, and come again. Fast fashion has given rise to rapid consumerism. Luxury fashion has undergone greater scrutiny, while secondhand and vintage markets have become media darlings. Social media platforms and influencers have undoubtedly impacted the collective zeitgeist surrounding style. While romanticism and commercialization of fashion are default stances for many, perhaps skepticism—and reflection—have never been more important.

Fashion’s manifestations are tethered to times, places, languages, memories and peoples. We became fascinated by what it meant to study fashion in the past, and what does the study of fashion mean for the future? In this way, we dissolve the boundaries of past, present and future and invite both nostalgia and progress into the conversation. We invite you to reflect with us and to view each authors’ piece as a facet of this evolving field.

Ed. Note from FSJ:

FSJ: The Fashion Studies Journal was founded in 2012 by five students in the Fashion Studies MA program at Parsons. The initial purpose of the journal was to give graduate students a place to get their feet wet in academic publishing as well as to make connections between early-career scholars from around the world.

This many years later, the journal continues as an independent publishing outlet for anyone who wants to think and write about fashion in a curious, critical way, but our ethos of inclusivity and providing opportunity for fledgling scholars remains.

Welcoming a team of students from this year’s MAFS cohort to guest edit an issue was a way to honor the journal’s roots in the Parsons community and to pass along what we believe FSJ has always stood for, which is a spirit of radical can-do creativity and an enthusiasm for building community through collaboration, particularly for people entering what can be an intimidating field.

Kudos to the team for putting together a beautiful, expansive issue that reflects not only what fashion studies looks like in 2025 but how it has grown and changed, as well as how it can continue to push conversations forward across disciplines. You’re always welcome at FSJ!

Image By Fangchi Liu.

Image By Fangchi Liu.The guest editorial team from Parsons was: Kayla Mutchler, Dylan Howell, Gillian Arthur, Marissa Scharlau, Chris Ziebert, Wiktoria Gawor, Catherine Gerdes, Courtney Broadnax, Olivia Kulin, Ella Franch, Claudia Sànchez San Miguel, and Hannah McIntyre

Graphic design by Gillian Arthur and Claudia Sànchez San Miguel.

Social media design by Olivia Kulin.

Illustrations by Fangchi Liu.

Graphic design by Gillian Arthur and Claudia Sànchez San Miguel.

Social media design by Olivia Kulin.

Illustrations by Fangchi Liu.

Dr Julie Gork is a Lecturer in the School of Fashion and Textiles at RMIT University. She holds a PhD (Fashion & Textiles) from RMIT University and an MA (Fashion Studies) from Parsons School of Design. Her research interests include fashion theory, sensory knowledge, and fashion diversity, including disability.

Alla Eizenberg is a Part-Time Assistant Professor in the School of Fashion, Parsons School of Design, New York and a PhD candidate in the Department of Design, Aalto University, Espoo. Her research focuses on the everyday aesthetics and the use of dirt in luxury fashion commodities.

The 15th anniversary of Parsons’ Fashion Studies graduate program (MAFS) marks a significant moment in the institutionalization of fashion as an academic field. It is an opportunity to honor the vision and dedication of the founding scholars who established fashion as a legitimate field of study and to share some of the current concerns that continue to haunt and shape the field. The early writing on fashion was grounded in a variety of traditional academic disciplines that provided clear theoretical frameworks and methodologies, including sociology, anthropology, philosophy, art history, material culture, and cultural studies, among others. However, as fashion studies emerges as a field in its own right, the hybridity of research methods that was invaluable for the development of the innovative and critical approaches necessary to legitimize fashion as a subject of study also poses challenges to the academic rigor of the field.

At this moment, fashion studies faces existential questions: Does its strength in multi-methodological approaches undermine academic legitimacy? And does its ability to draw from many disciplines and fields raise fundamental questions about disciplinary identity? As graduates of the MAFS program who have pursued doctoral studies, we consider this anniversary a fitting moment to examine some of these questions and to join other scholars reflecting on the state of the field. [1] But unlike scholars who entered fashion studies from traditional academic disciplines, we write from the standpoint of the first generation of scholars trained specifically in fashion studies, equipped with its interdisciplinary toolkit but lacking the methodological depth of traditional disciplines. This article draws from our experiences to consider how the varied research practices of fashion studies contribute to its interdisciplinary identity and, by extension, to our own identities as fashion studies scholars.

We started our careers in the fashion industry, albeit on different continents, before discovering the growing field of fashion studies. Alla Eizenberg spent fifteen years as a practicing fashion designer, working in Italy, Israel, and France. In 2006 she founded Maison Rouge Homme, an upscale menswear brand, which she led as a creative director for seven years. During this time she was invited to teach fashion design, which sparked her interest in the academic study of fashion. Julie Gork worked for seven years as a fashion trend forecaster, gaining insight into the cultural phenomena of fashion. While she valued the creative and research aspects of the role, she also felt complicit in the consumption-driven imperatives of the industry. These industry backgrounds, which instigated our desire to critically examine the creative, social, cultural, and economic facets of fashion, illustrate just one of the ways in which people may arrive at the field.

We met as members of the sixth cohort of MAFS at Parsons in 2015, marking our entry into fashion studies, and to academia in a more general sense. The foundation we acquired under our distinguished faculty, including Hazel Clark, Heike Jenss, Francesca Granata, and Christina Moon, among others, provided comprehensive knowledge of fashion studies' theoretical landscape, making us confident in pursuing an academic path. However, our subsequent doctoral studies revealed a critical gap: while we possessed a solid understanding of fashion theory, we lacked the methodological depth that scholars from established disciplines often bring to their fashion research.

These methodological challenges became concrete during the development of our PhD methodologies, attempting to apply research methods without the disciplinary training traditionally associated with those approaches. Julie's qualitative research on the sensory experience of fashion and blindness raised questions about ethnographic competency. She wondered how to apply anthropological methods, like sensory ethnography, without formal anthropological training. As a result, she qualified the methodology as an ethnographic approach to qualitative research to acknowledge disciplinary traditions and definitions. Similarly, Alla encountered challenges when conducting research on designers’ incentives for referencing dirt in high-end fashion commodities. Lacking clear guidelines on qualitative interviews, and insufficient expertise with data analysis, she felt unprepared for the methodological rigor exercised by her peers educated in sociology. These encounters underline a broader challenge facing fashion studies programs, ultimately raising a question: how to prepare scholars who can engage critically with fashion while meeting the methodological standards expected in broader academic contexts.

At this moment, fashion studies faces existential questions: Does its strength in multi-methodological approaches undermine academic legitimacy? And does its ability to draw from many disciplines and fields raise fundamental questions about disciplinary identity? As graduates of the MAFS program who have pursued doctoral studies, we consider this anniversary a fitting moment to examine some of these questions and to join other scholars reflecting on the state of the field. [1] But unlike scholars who entered fashion studies from traditional academic disciplines, we write from the standpoint of the first generation of scholars trained specifically in fashion studies, equipped with its interdisciplinary toolkit but lacking the methodological depth of traditional disciplines. This article draws from our experiences to consider how the varied research practices of fashion studies contribute to its interdisciplinary identity and, by extension, to our own identities as fashion studies scholars.

Discovering Fashion Studies

We started our careers in the fashion industry, albeit on different continents, before discovering the growing field of fashion studies. Alla Eizenberg spent fifteen years as a practicing fashion designer, working in Italy, Israel, and France. In 2006 she founded Maison Rouge Homme, an upscale menswear brand, which she led as a creative director for seven years. During this time she was invited to teach fashion design, which sparked her interest in the academic study of fashion. Julie Gork worked for seven years as a fashion trend forecaster, gaining insight into the cultural phenomena of fashion. While she valued the creative and research aspects of the role, she also felt complicit in the consumption-driven imperatives of the industry. These industry backgrounds, which instigated our desire to critically examine the creative, social, cultural, and economic facets of fashion, illustrate just one of the ways in which people may arrive at the field.

We met as members of the sixth cohort of MAFS at Parsons in 2015, marking our entry into fashion studies, and to academia in a more general sense. The foundation we acquired under our distinguished faculty, including Hazel Clark, Heike Jenss, Francesca Granata, and Christina Moon, among others, provided comprehensive knowledge of fashion studies' theoretical landscape, making us confident in pursuing an academic path. However, our subsequent doctoral studies revealed a critical gap: while we possessed a solid understanding of fashion theory, we lacked the methodological depth that scholars from established disciplines often bring to their fashion research.

These methodological challenges became concrete during the development of our PhD methodologies, attempting to apply research methods without the disciplinary training traditionally associated with those approaches. Julie's qualitative research on the sensory experience of fashion and blindness raised questions about ethnographic competency. She wondered how to apply anthropological methods, like sensory ethnography, without formal anthropological training. As a result, she qualified the methodology as an ethnographic approach to qualitative research to acknowledge disciplinary traditions and definitions. Similarly, Alla encountered challenges when conducting research on designers’ incentives for referencing dirt in high-end fashion commodities. Lacking clear guidelines on qualitative interviews, and insufficient expertise with data analysis, she felt unprepared for the methodological rigor exercised by her peers educated in sociology. These encounters underline a broader challenge facing fashion studies programs, ultimately raising a question: how to prepare scholars who can engage critically with fashion while meeting the methodological standards expected in broader academic contexts.

Illustration by Fangchi Liu

Illustration by Fangchi LiuMethodology Matters

According to Steiner Kvale, the original Greek meaning of the word method is “a route that leads to the goal.” [2] This definition highlights the importance of mastering a method as a foundational skill for achieving a goal, which in our case is rigorous and sound scholarly work. In many academic contexts—such as group discussions, conference applications, and peer-reviewed publications—the chosen research method signals scholarly identity. Within fashion studies, methodological diversity enables innovation in research design. Yet, as Marco Pedroni warns, "despite its strengths, interdisciplinarity poses challenges for fashion studies" due to potential fragmentation resulting from diverse theoretical and methodological demands. [3] So while interdisciplinary training enables innovative approaches to address the complexity of fashion research, it also invites scrutiny regarding methodological competency and scholarly authority, challenges familiar to other emerging interdisciplinary fields.

Heike Jenss’ edited collection remains one of the most robust contributions to fashion research methods, featuring a wide range of theoretically sound and original studies. [4] However, a close examination reveals that contributors often draw upon disciplinary training in traditional fields, which lends credibility and depth to their analyses. This positioning reflects the value of interdisciplinary contributions made by scholars entering the field from elsewhere. For these scholars, it is a positionality that may create a feeling of being both "in" and "out" of fashion studies, as described by Ben Barry and Alison Matthews David. [5] Their experience of crossing academic boundaries contrasts sharply with our position as scholars who began our academic careers firmly "in" fashion studies. Where Barry and Matthews David describe the "privilege inherent in traversing academic boundaries," we encountered the challenge of defending our disciplinary legitimacy from within an interdisciplinary field that lacks clear methodological criteria.

Our own doctoral experiences revealed that identifying as "fashion studies scholars" carried less academic weight than identification with established disciplines, highlighting the field's ongoing struggle for institutional recognition. What makes matters worse is a certain popularity of fashion as a research subject. In our respective PhD paths, we encountered peers from cultural studies, art history, design, and textile science who, while working on fashion-related topics, possessed training in established research traditions rooted in their home disciplines. More significantly, we met scholars from philosophy, sociology, and history who were producing fashion research while remaining largely unaware of fashion studies' theoretical contributions. This pattern suggests that fashion as a research subject is being claimed by multiple disciplines without necessarily acknowledging fashion studies as a legitimate field of expertise. This distinction is crucial. Scholars who arrive at fashion studies with established disciplinary training bring investigative credibility, while those trained specifically in fashion studies must justify their scholarly competence. So, we wonder if the legacy of fashion as a denigrated subject persists. Does a lack of cohesive research practices reinforce perceptions of fashion studies as a young academic field or a "frivolous academic child"?

From the Periphery

Our experiences highlight both the possibilities and difficulties facing fashion studies as it continues to evolve as an academic field. We are confident that the answer lies neither in abandoning interdisciplinarity nor in the enforcement of a singular "fashion studies approach." For new fashion scholars, the density of interdisciplinary entanglements and possibilities of methods can be overwhelming, so we advocate for a stronger emphasis on methodological literacy within curricula. [6] This includes exposure to diverse research techniques and critical engagement with their appropriate application. Students should learn to assess their own methodological competencies and to recognize when collaboration is essential for constructing a rigorous and coherent research design. Collaborative frameworks can help address the challenges of interdisciplinary inquiry by pooling expertise across different research practices. Instead of placing the burden on individual scholars to master multiple methods independently, such frameworks promote shared methodological competence tailored to the complexities of fashion research.

Nearly a decade ago, Christopher Breward (2016) observed that the field of fashion studies thrived at the periphery with diverse approaches and methodologies to fuel its academic recognition. The questions we raise here reflect the growing pains of an academic field coming into its own. As fashion studies continues to mature, we must balance the vitality of its interdisciplinary foundations with the need for methodological clarity that commands academic respect. The future of the field lies in developing sophisticated, collaborative approaches that uphold both our intellectual heritage and our commitment to scholarly excellence.

Notes: What Makes a Fashion Scholar?

[1] Marco Pedroni, "The Evolution of a Discipline: A Transformative Chapter in Fashion Studies," International Journal of Fashion Studies 12, no. 1 (2025): 3-16; Ben Barry and Alison Matthews David, "A Fashion Studies Manifesto: Toward an (Inter)disciplinary Field," Fashion Studies, special issue "State of the Field," 2, no. 1 (2023): 1-23; Christopher Breward, "Foreword," in Fashion Studies: Research Methods, Sites and Practices, ed. Heike Jenss (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), xvii–xx; Heike Jenss, "Introduction. Locating Fashion Studies: Research Methods, Sites and Practices," in Fashion Studies: Research Methods, Sites and Practices, ed. Heike Jenss (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2016), 1-18; Francesca Granata, "Fashion Studies In-Between: A Methodological Case Study and an Inquiry into the State of Fashion Studies," Fashion Theory 16, no. 1 (2012): 67-82.

[2] Carol Warren, "Qualitative interviewing," in Qualitative interviewing, eds. J. F. Gubrium and J. A. Holstein (SAGE Publications, 2001), 83-102.

[3] Pedroni, “The Evolution of a Discipline”, 9.

[4] Heike Jenss, ed, Fashion Studies: Research Methods, Sites and Practices, (London; New York: Bloomsbury, 2016).

[5] Barry and Matthews David, "A Fashion Studies Manifesto”.

[6] Jenss, "Introduction. Locating Fashion Studies”, 11.

Image by Mike Thompson.

Image by Mike Thompson.

Sara Idacavage, Ph.D., is Assistant Professor of Fashion Media at Southern Methodist University. In addition to historical and cultural scholarship, her research focuses on transforming fashion education through sustainable thinking.

Lauren Downing Peters, Ph.D., is Associate Professor of Fashion Studies and Director of the Fashion Study Collection at Columbia College Chicago. Her research focuses on the history of plus-size fashion, the lived experience of fat sartorial embodiment, reconsidered histories of American fashion, and transformed and inclusive fashion pedagogies.

When we began the MA Fashion Studies program at Parsons, sustainability was not yet central to our academic work. Today, it has become the driving force behind our practice. Over the past fifteen years, the term “sustainable fashion” has become both increasingly visible and frustratingly vague. While its rise in public discourse has signaled a broader cultural awareness, it has also been diluted by notions of “green growth.” Even with years of experience in this space, we continue to ask ourselves whether our teaching is making a tangible impact—especially in an industry, and an educational system, still anchored in growth, speed, and overproduction.

As graduates of the MA Fashion Studies program at Parsons (Lauren in 2012 and Sara in 2014) and longtime FSJ editors (Lauren co-founding the journal in 2011 and Sara joining the editorial team the following year), we’ve been inspired by how much the publication and community have grown over the years. This special issue—and the forthcoming release of our co-edited book, Teaching Fashion Studies: Pedagogy, Perspectives, Practice (projected to be released in 2026)—offered us an opportunity to pause and reflect on how our thinking has shifted and our pedagogy has evolved. The following dialogue, composed across time zones via a series of long text messages exchanged between France, Spain, and the United States, captures an ongoing conversation between friends and colleagues about the challenges and joys of teaching sustainability. In sharing it, we hope to underscore the value of peer dialogue and critical self-reflection in a field that often privileges productivity over pause and individualism over community.

As graduates of the MA Fashion Studies program at Parsons (Lauren in 2012 and Sara in 2014) and longtime FSJ editors (Lauren co-founding the journal in 2011 and Sara joining the editorial team the following year), we’ve been inspired by how much the publication and community have grown over the years. This special issue—and the forthcoming release of our co-edited book, Teaching Fashion Studies: Pedagogy, Perspectives, Practice (projected to be released in 2026)—offered us an opportunity to pause and reflect on how our thinking has shifted and our pedagogy has evolved. The following dialogue, composed across time zones via a series of long text messages exchanged between France, Spain, and the United States, captures an ongoing conversation between friends and colleagues about the challenges and joys of teaching sustainability. In sharing it, we hope to underscore the value of peer dialogue and critical self-reflection in a field that often privileges productivity over pause and individualism over community.

Lauren

These days, we’re both deeply involved in fashion sustainability as educators, but was it something you were thinking about (or even aware of) when you started the MAFS?

These days, we’re both deeply involved in fashion sustainability as educators, but was it something you were thinking about (or even aware of) when you started the MAFS?

Sara

Not at all! When I first started at Parsons, I was still a bit of a fast fashion-addict who was just dazzled by the glamour of the industry and the allure of the museum world. I knew that I wanted to have some greater impact on the world of fashion, but I wasn’t yet aware of the extent of the issues that are present in the industry. How about you?

Not at all! When I first started at Parsons, I was still a bit of a fast fashion-addict who was just dazzled by the glamour of the industry and the allure of the museum world. I knew that I wanted to have some greater impact on the world of fashion, but I wasn’t yet aware of the extent of the issues that are present in the industry. How about you?

Lauren

No. Definitely not. I think I only became aware of fashion sustainability in the Fashion Cultures class during the second semester of the MAFS. Mary Ping of Slow and Steady Wins the Race was a guest speaker and I found her sort of “winking” approach to slow fashion to be both refreshing and brilliant. I didn’t really get serious about fashion sustainability—specifically, as a personal pursuit—until I was doing my PhD. What about you? What was your “aha” moment…your villain origin story?

No. Definitely not. I think I only became aware of fashion sustainability in the Fashion Cultures class during the second semester of the MAFS. Mary Ping of Slow and Steady Wins the Race was a guest speaker and I found her sort of “winking” approach to slow fashion to be both refreshing and brilliant. I didn’t really get serious about fashion sustainability—specifically, as a personal pursuit—until I was doing my PhD. What about you? What was your “aha” moment…your villain origin story?

Sara

I suppose my interest really came from working in museums and archives and pursuing fashion history academically. My thesis at Parsons was about the rise of American ready-to-wear, which made me want to learn more about how people obtained clothing before ready-made production.

The more I learned about the history of clothing consumption and became more attuned to the materiality of garments through archival research and a growing love of vintage, I began to question my own fashion choices and consumption habits. I wanted to understand how things got this way—not just accept the idea that “people want more stuff.” That ultimately led me to shift my teaching approaches and, eventually, pursue a PhD.

What made you get “serious” about it during your PhD? Had anything notable changed for you between then and when you first started the MAFS program?

I suppose my interest really came from working in museums and archives and pursuing fashion history academically. My thesis at Parsons was about the rise of American ready-to-wear, which made me want to learn more about how people obtained clothing before ready-made production.

The more I learned about the history of clothing consumption and became more attuned to the materiality of garments through archival research and a growing love of vintage, I began to question my own fashion choices and consumption habits. I wanted to understand how things got this way—not just accept the idea that “people want more stuff.” That ultimately led me to shift my teaching approaches and, eventually, pursue a PhD.

What made you get “serious” about it during your PhD? Had anything notable changed for you between then and when you first started the MAFS program?

Lauren

I think I got serious about sustainability because of the “Sweden” of all of it. To provide our readers (Hello!) with some context, I moved to Sweden to pursue my doctorate at the Centre for Fashion Studies at Stockholm University. There, I quickly learned that fashion sustainability is very intrinsic to Swedish style.

Everyone I met seemed to have small, tightly curated wardrobes filled with timeless, high-quality pieces, and many Swedish brands encouraged circularity by consigning gently used pieces alongside their new items.

I guess, to put it simply, my time in Stockholm introduced me to a new way to relate to and consume fashion. In my efforts to fit in, I just started to shop more like a Swede, and as such I became increasingly versed in sustainability issues.

I also learned a lot from you during that period as we were both working pretty intensely on FSJ together—both through your writing and our regular meetings. I’m pretty sure it was you who introduced me to Dana Thomas’ Fashionopolis and Britt Wray’s Generation Dread, so thank you, friend!

Can you talk a little about how you got serious about fashion sustainability during your PhD? And how did your research eventually come to (re)shape your pedagogy?

I think I got serious about sustainability because of the “Sweden” of all of it. To provide our readers (Hello!) with some context, I moved to Sweden to pursue my doctorate at the Centre for Fashion Studies at Stockholm University. There, I quickly learned that fashion sustainability is very intrinsic to Swedish style.

Everyone I met seemed to have small, tightly curated wardrobes filled with timeless, high-quality pieces, and many Swedish brands encouraged circularity by consigning gently used pieces alongside their new items.

I guess, to put it simply, my time in Stockholm introduced me to a new way to relate to and consume fashion. In my efforts to fit in, I just started to shop more like a Swede, and as such I became increasingly versed in sustainability issues.

I also learned a lot from you during that period as we were both working pretty intensely on FSJ together—both through your writing and our regular meetings. I’m pretty sure it was you who introduced me to Dana Thomas’ Fashionopolis and Britt Wray’s Generation Dread, so thank you, friend!

Can you talk a little about how you got serious about fashion sustainability during your PhD? And how did your research eventually come to (re)shape your pedagogy?

Sara

Pursuing a PhD only became a goal after I began rethinking how I was teaching fashion history and how it could be reframed through the lens of sustainability. By the end of 2019, I applied to a PhD program without a clear roadmap, since “fashion history with an emphasis on sustainability” wasn’t exactly a degree path—yet. A few months (and a global pandemic) later, I landed at the University of Georgia.

With no existing sustainable fashion courses at UGA, I got creative with electives and was particularly influenced by a class called “Sustainability and Education,” taken alongside K–12 science and social studies teachers. Ironically, stepping outside fashion helped me reimagine how to teach it.

Designing a sustainable fashion syllabus as part of my comprehensive exams led me to teaching UGA’s first course on the subject in 2023, and my dissertation—on mail-order catalogs as an early form of “fast fashion”—was basically a long experiment in teaching history through a sustainability lens. I’m now bringing that work to life in my new(ish) role at SMU, which feels deeply rewarding.

What was your experience like starting a sustainable fashion class at your school, and how has it changed over time?

Pursuing a PhD only became a goal after I began rethinking how I was teaching fashion history and how it could be reframed through the lens of sustainability. By the end of 2019, I applied to a PhD program without a clear roadmap, since “fashion history with an emphasis on sustainability” wasn’t exactly a degree path—yet. A few months (and a global pandemic) later, I landed at the University of Georgia.

With no existing sustainable fashion courses at UGA, I got creative with electives and was particularly influenced by a class called “Sustainability and Education,” taken alongside K–12 science and social studies teachers. Ironically, stepping outside fashion helped me reimagine how to teach it.

Designing a sustainable fashion syllabus as part of my comprehensive exams led me to teaching UGA’s first course on the subject in 2023, and my dissertation—on mail-order catalogs as an early form of “fast fashion”—was basically a long experiment in teaching history through a sustainability lens. I’m now bringing that work to life in my new(ish) role at SMU, which feels deeply rewarding.

What was your experience like starting a sustainable fashion class at your school, and how has it changed over time?

Lauren

I’d say overall it was very fulfilling, and perhaps one of the most meaningful things I’ve done since joining the faculty at Columbia College Chicago in 2018.

I developed the course in response to a call for new proposals for Columbia’s general education core. The idea was that this new suite of courses, taught by interdisciplinary faculty, would engage both the Columbia and wider Chicago communities.

In the short while that I’d lived in Chicago (this was in 2019), I had quickly come to appreciate just how robust the sustainable fashion community is there, from practitioners like Jaime Hayes of Production Mode to organizations like Chicago Fair Trade. I decided to develop a course that took students outside of the classroom to engage with this community.

Like you, I took my students to a recycling center (horrifying!) and to sustainable boutiques (inspiring!), and tasked them with developing fashion sustainability initiatives within our own campus community, like clothing swaps and mending circles.

We, of course, did a lot of this work together—co-designing our assignments and providing talk therapy to one another when the going got rough. I think it is notable that we were so intentional about doing this work in community with one another. Why was this so important to you?

I’d say overall it was very fulfilling, and perhaps one of the most meaningful things I’ve done since joining the faculty at Columbia College Chicago in 2018.

I developed the course in response to a call for new proposals for Columbia’s general education core. The idea was that this new suite of courses, taught by interdisciplinary faculty, would engage both the Columbia and wider Chicago communities.

In the short while that I’d lived in Chicago (this was in 2019), I had quickly come to appreciate just how robust the sustainable fashion community is there, from practitioners like Jaime Hayes of Production Mode to organizations like Chicago Fair Trade. I decided to develop a course that took students outside of the classroom to engage with this community.

Like you, I took my students to a recycling center (horrifying!) and to sustainable boutiques (inspiring!), and tasked them with developing fashion sustainability initiatives within our own campus community, like clothing swaps and mending circles.

We, of course, did a lot of this work together—co-designing our assignments and providing talk therapy to one another when the going got rough. I think it is notable that we were so intentional about doing this work in community with one another. Why was this so important to you?

Sara

First, I have to give credit where it’s due! Plenty of fashion educators were laying the groundwork for sustainability in fashion long before I even started teaching.

For example, there’s Kate Fletcher, who I know we both admire. She was publishing on sustainable fashion before I even really knew what the term meant. At Parsons, groundbreaking educators like my friend Timo Rissanen really shaped how I thought about this work. The list of people who did this work before us could go on and on…

That said, as we know, much of this “early” work was happening in elite art schools or in European institutions. It’s only (relatively) more recently that sustainability started embedding itself into larger and more traditional programs in the U.S.

Which brings me to your question about community. As we’ve written in FSJ before, academia is a precarious world in which I believe collaboration is entirely necessary. I never took a sustainability course in school, so I had a serious case of imposter syndrome when I first started teaching it. Plus, I was a recovering fast fashion addict with minimal sewing skills—who was I to talk?

And let’s not forget the mental health side of this work. We’ve both been in that “valley of despair,” wondering if any of it even matters in the grand scheme of things. But knowing that you and many of my other passionate friends and colleagues were out there, trying things, really kept me going. Sometimes it’s just enough just to say, “Yep, I feel kind of hopeless too,” and not feel alone in that.

Which brings us to our book! I know we’re both so excited about this project because it offers exactly what we once needed: examples from innovative educators from diverse fields that show how sustainability can be taught with creativity and care. Can you talk about how it came to life and what you hope it will spark in our growing community?

First, I have to give credit where it’s due! Plenty of fashion educators were laying the groundwork for sustainability in fashion long before I even started teaching.

For example, there’s Kate Fletcher, who I know we both admire. She was publishing on sustainable fashion before I even really knew what the term meant. At Parsons, groundbreaking educators like my friend Timo Rissanen really shaped how I thought about this work. The list of people who did this work before us could go on and on…

That said, as we know, much of this “early” work was happening in elite art schools or in European institutions. It’s only (relatively) more recently that sustainability started embedding itself into larger and more traditional programs in the U.S.

Which brings me to your question about community. As we’ve written in FSJ before, academia is a precarious world in which I believe collaboration is entirely necessary. I never took a sustainability course in school, so I had a serious case of imposter syndrome when I first started teaching it. Plus, I was a recovering fast fashion addict with minimal sewing skills—who was I to talk?

And let’s not forget the mental health side of this work. We’ve both been in that “valley of despair,” wondering if any of it even matters in the grand scheme of things. But knowing that you and many of my other passionate friends and colleagues were out there, trying things, really kept me going. Sometimes it’s just enough just to say, “Yep, I feel kind of hopeless too,” and not feel alone in that.

Which brings us to our book! I know we’re both so excited about this project because it offers exactly what we once needed: examples from innovative educators from diverse fields that show how sustainability can be taught with creativity and care. Can you talk about how it came to life and what you hope it will spark in our growing community?

Lauren

Like you, I felt a bit of imposter syndrome when I began teaching my sustainability course, and while there were so many wonderful resources (books, films, podcasts, etc.) to share with students, there wasn’t really anyone out there talking about how to mobilize these ideas in the classroom outside of design techniques. I wasn’t content to just review sustainability concepts; I wanted to give my students meaningful tools to “do” fashion sustainability in their own lives. I also wanted to create spaces for them to feel a little less alone and a little more empowered.

In our work, we discussed how helpful it would be to develop some kind of fashion sustainability network to share ideas with other educators. We first tested this idea at the “De-Fashioning Education” symposium at the University of the Arts, Berlin in 2023. I think this workshop really was the catalyst for us to develop the book proposal with Bloomsbury.

We put out a CFP and received over 100 submissions (wonderful, but overwhelming!) that we whittled down to 60 concise chapters. It’s only just barely underway, but I’m so proud of the global reach of the volume and the clever and critical ways our contributors approach the subject of fashion sustainability.

In terms of what I hope the book will spark in our community, most simply I just hope that it makes fashion sustainability attainable and actionable. If I’m thinking more ambitiously and expansively, I hope it will effect meaningful, systemic change in fashion education.

What about you? I’d also love to hear about how you’re doing right now. Is this project helping to pull you out of the valley of despair?

In our work, we discussed how helpful it would be to develop some kind of fashion sustainability network to share ideas with other educators. We first tested this idea at the “De-Fashioning Education” symposium at the University of the Arts, Berlin in 2023. I think this workshop really was the catalyst for us to develop the book proposal with Bloomsbury.

We put out a CFP and received over 100 submissions (wonderful, but overwhelming!) that we whittled down to 60 concise chapters. It’s only just barely underway, but I’m so proud of the global reach of the volume and the clever and critical ways our contributors approach the subject of fashion sustainability.

In terms of what I hope the book will spark in our community, most simply I just hope that it makes fashion sustainability attainable and actionable. If I’m thinking more ambitiously and expansively, I hope it will effect meaningful, systemic change in fashion education.

What about you? I’d also love to hear about how you’re doing right now. Is this project helping to pull you out of the valley of despair?

Sara

To be honest, I think I’ve already dipped in and out of the “valley of despair” a few times during this conversation—but that’s just how I am!

But there is some real value in reflecting with you. A decade ago, I knew very little about sustainability, and now I’ve shared what I’ve learned with hundreds of students. That’s got to count for something, right? Even getting one student to pause before adding something to their Shein cart feels like a small win.

Our book project has honestly helped me stay optimistic, in big part because it’s kept me connected to you and to others who actually want to share, collaborate, and connect on a personal level. Unfortunately, that can be a bit rare in academia, where things can feel siloed and competitive.

So to bring it full circle, what do you think has really shifted since our Parsons days? Or, if you could time travel, what advice would you give your past self?

To be honest, I think I’ve already dipped in and out of the “valley of despair” a few times during this conversation—but that’s just how I am!

But there is some real value in reflecting with you. A decade ago, I knew very little about sustainability, and now I’ve shared what I’ve learned with hundreds of students. That’s got to count for something, right? Even getting one student to pause before adding something to their Shein cart feels like a small win.

Our book project has honestly helped me stay optimistic, in big part because it’s kept me connected to you and to others who actually want to share, collaborate, and connect on a personal level. Unfortunately, that can be a bit rare in academia, where things can feel siloed and competitive.

So to bring it full circle, what do you think has really shifted since our Parsons days? Or, if you could time travel, what advice would you give your past self?

Lauren

I think the biggest shift for me is that I now have a very, very strong desire for my work (teaching and research) to be more grounded. There was a long period where I associated rigor and value with inaccessible theory and academic jargon, but like you I’ve increasingly come to appreciate the small wins—such as hearing that a student had a conversation with a family member about their Amazon.com dependency, or that they are now reading fabric composition labels before making a purchase. I can only hope that these small behavior changes and shifts in perspective will reverberate outward into their work as fashion professionals.

I realize I started this dialogue so it’s only appropriate that you end it! Any final, final words for our community?

I think the biggest shift for me is that I now have a very, very strong desire for my work (teaching and research) to be more grounded. There was a long period where I associated rigor and value with inaccessible theory and academic jargon, but like you I’ve increasingly come to appreciate the small wins—such as hearing that a student had a conversation with a family member about their Amazon.com dependency, or that they are now reading fabric composition labels before making a purchase. I can only hope that these small behavior changes and shifts in perspective will reverberate outward into their work as fashion professionals.

I realize I started this dialogue so it’s only appropriate that you end it! Any final, final words for our community?

Sara

I’m not sure my own words can fully capture what I want to express here, so I’ll just end with a quote from the Earth Logic Research Plan that continues to guide my work. In it, Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham write: “The area of work that matters most is the one which is actionable by you, in your context, today. Time is short. Every decision counts. It is incumbent upon all of us to take action within the conditions of our own lives, to find ways to bring a sense of urgency and responsibility into our daily decision-making processes.” [1]

I’m not sure my own words can fully capture what I want to express here, so I’ll just end with a quote from the Earth Logic Research Plan that continues to guide my work. In it, Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham write: “The area of work that matters most is the one which is actionable by you, in your context, today. Time is short. Every decision counts. It is incumbent upon all of us to take action within the conditions of our own lives, to find ways to bring a sense of urgency and responsibility into our daily decision-making processes.” [1]

Notes: Fashion Sustainability, Then and Now

[1] Kate Fletcher and Mathilda Tham, Earth Logic Action Research Plan (2019), 25.

Aude Fellay is a writer, researcher, and teacher. She coordinates and teaches theory courses in the MA program in Fashion, Jewellery, and Accessory Design at HEAD-Genève, where she is also engaged in practice-based research. Her writing explores contemporary fashion, image culture, and labor. Her work has been featured in publications such as Dune Journal, Issue Journal, and Revue Faire.

In her landmark book Fashion at The Edge, Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness, Caroline Evans gives weight to fashion design as a form of cultural analysis. [1] In a recent interview with Rosie Findlay about the publication, Evans acknowledges that the book’s method registers as a “sort of mimicry” or “perhaps an echo?” of fashion design’s own operations. [2] From my perspective, as a “theorist” [3] surrounded by practitioners, and in a perpetual struggle against the incessant infantilization of the practice, her writing conveys more than an echo of fashion design. Despite it being theory-heavy, it goes some way in narrowing the gap between theory and practice as institutional categories, by theoretically “testing” the methods of “creative” fashion design. [4] Put differently, it mobilizes fashion design methodologies, which it simultaneously helps to foreground, “assuming an equivalent between the historian and the designer.” [5] As such, the book—and her work more broadly—offers fashion design a form of legitimacy as a mode of inquiry and highlights its specificities in ways that do not reiterate false oppositions between the material and immaterial elements of fashion. What follows, then, is a very brief attempt to point out the significance of Evans’s work not simply as fashion history but as a resource for the further formalization of practice-based research in fashion at a moment when its stakes and formats are being outlined. I have set out to do this in the wake of having almost concluded a two-year long practice-based project at HEAD–Genève (HES-SO). Here—to borrow from the Virgil Abloh playbook—I am “postrationalizing” Evans’s contribution from the standpoint of that project and elaborating on the project itself to highlight ways we might “stay with the practice” as we transform it.

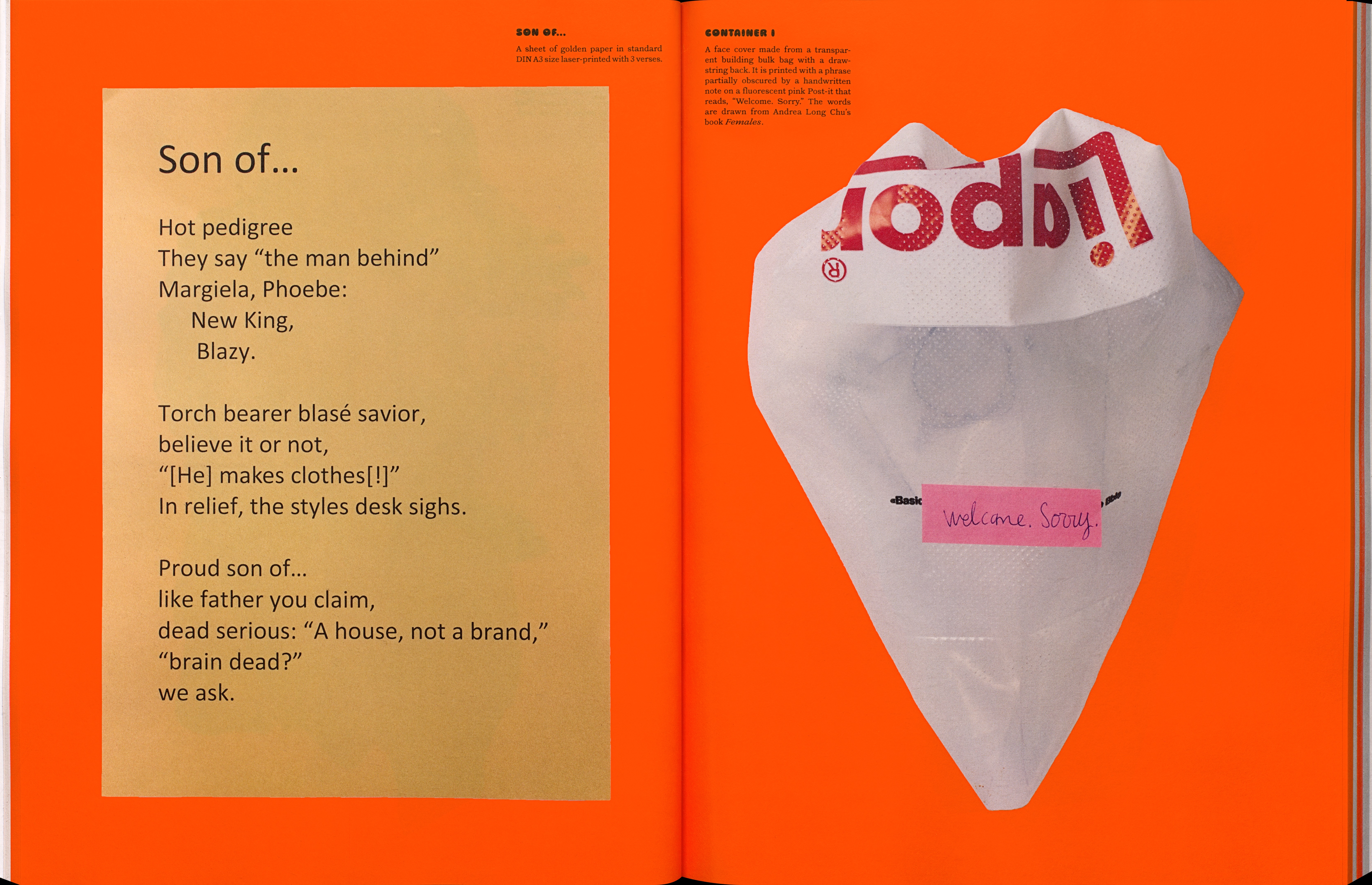

The first edition of Fashion at The Edge. A second edition was released in 2023.

The first edition of Fashion at The Edge. A second edition was released in 2023.The Wall

The hurdles fashion studies faced as it entered the academy have been well documented. [6] The obstacles facing fashion design as it follows the same path—some forty years after the fields of art, design, and architecture did—are even greater. [7] Firstly, practice-based research, regardless of the practice in question, still suffers from a lack of credibility. [8] Additionally, in the case of fashion, its academic field’s increased criticism of fashion design and the fashion industry more broadly have—and justly so—raised serious concerns about the practice itself. [9] This has resulted in both a permission to rethink how fashion is done and a steeper “wall of articulation” for fashion design as research. [9] In other words, the internal and external pressures of criticality and criticism have raised the bar “when it comes to proving [fashion design’s] activities and endeavors are worthwhile.” [10]

It is tempting, in this context, to salvage the practice of fashion design by repackaging it as art. As José Teunissen notes, fashion designers turned researchers have looked to “performances, installations, interventions, films and exhibitions…to replace the classic representations such as the catwalk, the fashion magazine and the fashion campaign,” valuing “the design process and the story above the artefact.” [11] Like Evans, I am uncomfortable with fashion’s strategic alignment with art, not least because, as she puts it, “fashion is plenty interesting enough.” [12] I do, however, understand its logic as a survival strategy for practitioners. In any case, clarifying the specificities of fashion’s practice, in its diverse contexts, is a worthwhile endeavor in light of both a growing interest in practice-based research and art’s more longstanding tradition of artistic research. To this end, I find myself going back to Evans’ work for ways of thinking about fashion design that attend to fashion as a design practice with its own methods, formats, constraints, and contexts.

Top: One of the “iconic” objects we chose as starting points was the Maison Martin Margiela veil. Shown here are examples of artifacts we developed in response. The piece on the left was produced by @knitgeekproject (Valentine Ebner), while the mask on the right was created through the upcycling of garments.

Bottom: The artifacts progressively departed from the original item as the research advanced.

Top: One of the “iconic” objects we chose as starting points was the Maison Martin Margiela veil. Shown here are examples of artifacts we developed in response. The piece on the left was produced by @knitgeekproject (Valentine Ebner), while the mask on the right was created through the upcycling of garments.

Bottom: The artifacts progressively departed from the original item as the research advanced. “I find myself going back to Evans’ work for ways of thinking about fashion design that attend to fashion as a design practice with its own methods, formats, constraints, and contexts.”

A “New” Form of Cultural Analysis

Evans’ Fashion at The Edge, first published in 2003, is “a case study of a method,” which she directs at the work of designers of the late 1990s. [13]Collecting concepts and historical motifs, she moves from present to past, and past to present, to make sense of the ubiquity of spectacle and death in the work of designers such as John Galliano or Alexander McQueen, zooming in on the historical citations that permeate their work. The book homes in on fashion’s material underbelly, contextualizing the anxiety and trauma designs evoked among the large-scale transformations underway at the time: a technological revolution, globalization, a century coming to its conclusion. Her method takes cues from her subject matter: she writes how the designers of which she speaks design. [14] She made this clear at the time, writing that “ragpicking, as well as describing designers’ methods, is also a useful tool for the cultural historian in thinking about fashion today.”[15] In contextualizing her methodological choices and the breadth of the issues addressed, she goes some way in lending fashion design’s “cultural poetics” epistemological weight. [16] She does the latter by way of household names, looking for equivalent methods in the writings of Walter Benjamin (among others). [17]

Like many fashion designers, Evans “thinks through images,” drawing on her own images to illuminate the work of designers—the Benjaminian ragpicker being one of them. She unearths concepts and brings them to bear on fashion to both decipher its meanings and describe its operations. Italo Calvino’s “thinking through images” is an example drawn from another, influential essay of hers, which I have found particularly useful. [18] It is both concrete—it hints at designers’ visual research—and analytically productive. The term can be applied to the fact that designers create garments with an understanding of their narrative or conceptual function within broader compositions—a look and/or a collection. The expression also points to the emblematic quality of the processes and outputs: as Evans argues, images are transformed into objects, and objects into images. In this sense, it points at the central role of “dreamworlds,” not as ad hoc contextualization but as the deliberate materialization of a viewpoint, one that arises from the interaction of a design identity and a specific topic or theme. In many ways, then, her work underscores the specificities of fashion design as it is practiced in our shared context, puts forward concepts through which to apprehend it, and implicitly legitimizes its operations as ways of knowing. [19]

The second “iconic” object was the Louis Vuitton Speedy bag tagged by Steven Sprouse in a collaboration initiated by Marc Jacobs. Shown here, an artifact created in response to the Speedy and the opening chapters of the Vuitton series.

The second “iconic” object was the Louis Vuitton Speedy bag tagged by Steven Sprouse in a collaboration initiated by Marc Jacobs. Shown here, an artifact created in response to the Speedy and the opening chapters of the Vuitton series.“[W]e decided to look critically at our own context (the western fashion and luxury industry), and its golden age (the late 1990s—Evans’ purview), through the viewpoint of some of its ‘iconic’ objects.“

How To?

Granted, the knowledge produced by fashion design in this context is dependent upon the labor of the critic or the cultural historian. It must be inferred from the images and material translations designers conjure. But there are ways for practitioners to uncover that knowledge and reveal the medium’s potential as a mode of inquiry, and there are dissemination formats to be found within fashion design’s own methods. [20] When designer Emilie Meldem and I set out to conduct a practice-based research project, we decided to look critically at our own context (the western fashion and luxury industry), and its golden age (the late 1990s—Evans’ purview), through the viewpoint of some of its “iconic” objects. [21] The icons were fitting emblems for the industry and a manageable starting point for a more wide-ranging, anti-capitalist, and feminist critique of the fashion industry’s extractive nature and normative thrust. These objects were not only “iconic”—or rather, heralded as such by the industry—but evoked central elements of a fashion design practice: a design identity (a “DNA,” if you will), and a know-how or savoir-faire, which raised questions about materials and production. In short, our choice of objects would help us build our own DNA and savoir-faire.

Our research book—a tool commonly used by designers to document their research and process—became both a format for sharing our output and an analytical tool, through which we articulated our critique and postrationalized our design experiments. In it, our engagement with the icons takes the very literal form of a “detective story” (a term that Evans uses, in fact, to characterize the type of cultural analysis shaped by Walter Benjamin’s concept of the trace and fashion design’s ragpicking [22]). The research material is presented as a series of clues to be deciphered through their captions and the objects they correspond to. These materials provide context for both the icons and the artifacts we created in response, which indexed specific aspects of the original icons or embodied our critique of them. While the initial artifacts closely resembled the icons, they became increasingly distinct through successive iterations—a shift shaped, in part, by the evolving framework of the research, as we moved from an initial, “paranoid” reading of the icons, which focused on the economic system and patriarchal order underwriting them, to attempts at yielding “reparative” tools and practices. [23]

The research material was post-rationalized into a series of visual chapters, with captions offering interpretive clues.

The research material was post-rationalized into a series of visual chapters, with captions offering interpretive clues.It was clear to us from the start that to stick with the practice, we would have to design the artifacts on the basis of a design identity, and think of a specific know-how, as well as consider production issues. Our close reading of the Margiela veil and of Maison Margiela’s broader appeal as expressing a desire for collective design structures informed the design identity: we gave up on devising an identity as a duo to test what designing as a collective would actually entail. [24] In short, we took seriously the desires lodged in the stories we tell ourselves about these objects, while exposing their falsities (Margiela operated, like most design studios, hierarchically). We assembled a research team and looked for tools to address asymmetries, and make power visible and accessible within the group. [25] So, while we remained committed to fashion as an existing set of practices, we were equally determined to reshape it, drawing on the counter-hegemonic critiques of the theorists, activists, cultural workers, and practitioners in our lives—many of whom embodied several of these roles. [26]

Artifacts that respond to the Louis Vuitton bag, highlighting its components: the body is made of PVC-coated canvas, while the only leather elements are its handles.

Artifacts that respond to the Louis Vuitton bag, highlighting its components: the body is made of PVC-coated canvas, while the only leather elements are its handles.We extrapolated methods from fashion understood as not simply made of design, narrowly conceived as the making of objects, but a whole host of practices that surround it and enable it. Storytelling, and fashion’s own hybrid language (in our context, Franglais), informed the publication’s structure and tone, for example. From the perspective of practice that is often ridiculed or deemed incapable of critical thought, it was essential that we developed our methods and dissemination formats from within the confines of the practice. In fact, staying with the practice meant devising two final stand-alone objects based on the many artifacts produced. [27] This acted as a productive constraint. It compelled us to confront both practical and theoretical questions, which would have escaped us otherwise: how aesthetic decisions are made when a collective is involved, or what desire and success might look like for us, at both the level of the objects and our own life choices, for instance. A focus on the process alone would have led to different outcomes, arguably more theoretical than applied.

The chapters move from examining the object itself to documenting and reflecting on our partial responses and provisional solutions to the questions it raised.

The chapters move from examining the object itself to documenting and reflecting on our partial responses and provisional solutions to the questions it raised.Fashion research can be both “artistic” and result in concrete changes to the practice itself, providing its specificities and applied dimension are accounted for. Theoretical frameworks can be put to work, and find themselves refined in the process, perhaps especially when theorists and designers collaborate and titles loosen in the process. This is one of the epistemological potentials of (critical) practice-led research at this moment in time: the possibility to act upon the critiques it articulates—to do better in real time. Fashion’s proximity to desire means it is also uniquely positioned to engage in and render desirable projects of making a good life. Perhaps this is what Evans gestured at in a 2020 interview with Susanna Strömquist, where she proposed fashion activism (re)acquainted itself with utopia. [28]

Storytelling played a crucial role in sorting, connecting, and organizing the research material. The research book—designed in collaboration with Sereina Rothenberger and David Schatz of Hammer—is scheduled for publication by Rollo Press in 2026.

Storytelling played a crucial role in sorting, connecting, and organizing the research material. The research book—designed in collaboration with Sereina Rothenberger and David Schatz of Hammer—is scheduled for publication by Rollo Press in 2026.Notes: Thinking Through Fashion (Practically)

[1] Caroline Evans, Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness (Yale University Press, 2003).

[2] Rosie Findlay, “Revisiting Fashion at the Edge: An Interview with Caroline Evans,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 11, no. 2 (2024): 319-327.

[3] I do not hold the proper credentials, in the context of my own institution, to claim the title. I am PhD-less and a part-time member of staff.

[4] The word is a coded and loaded term that refers to art and design schools of the Global North with associations to the upper echelons of the fashion industry and its capitals.

[5] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 13.

[6] Valerie Steele, “The F Word,” *Lingua Franca* 1, no. 4 (April 1991): 17–20.

[7] For an introduction to the rise of practice-based research in fashion, see Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton “The Politics of Fashion Knowledge between Practice and Theory,” in Fashion Knowledge: Theories, Methods, Practice and Politics, ed. Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton (Intellect Ltd., 2024), 1–11.

[8] Yves Citton, “Ce que la recherche-création fait aux thèses universitaires,” Issue, 15 octobre 2024, https://www.hesge.ch/head/issue/publications/ce-la-recherche-creation-fait-aux-theses-universitaires-yves-citton

[9] The term, borrowed by Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta and Tere Vadén, from Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s work on scientific knowledge and indigenous communities, describes an asymmetrical relationship, or the idea that “the values and phenomena self-evident in communities of the artists may not be self-evident in communities of scientists.” Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta, and Tere Vadén, Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public (Peter Lang, 2014). On fashion studies’ critical turn, see for example Natalya Lusty, “Fashion Futures and Critical Fashion Studies,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 35, no. 6 (2021): 813-823.

[10] Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta, and Tere Vadén, Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public, 67.

[11] José Teunissen, “The Transformative Power of Practice-Based Fashion Research,” in Fashion Knowledge: Theories, Methods, Practice and Politics, ed. Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton (Intellect Ltd., 2024), 25.

[12] Caroline Evans, interview by Susanna Strömquist, “Challenging the Orthodoxy of Fashion from Within,” Critical Fashion Project, 2020, .

[13] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 4.

[14] As Evans notes, designers who were “economically marginal” yet “symbolically central” to the fashion industry in the late ’90s.

[15] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 11.

[16] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 13.

[17] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 12.

[18] Caroline Evans, “Yesterday’s Emblems and Tomorrow’s Commodities: The Return of the Repressed in Fashion Imagery Today,” in Fashion Cultures Revisited, 2nd ed., ed. Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church Gibson (Routledge, 2013). The article was originally published in 2000, and appears to lay the groundwork for Fashion at The Edge.

[19] Evans’ institutional home is also an art and design school.

[20] Monica Titton has raised the issue of format in practice-based research, noting that “the format of the journal, book, or magazine (...) seems ideally suited for the representation of practice-based research.” See Monica Titton, “Theory as Practice,” in Fashion Knowledge: Theories, Methods, Practice and Politics, ed. Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton (Intellect Ltd., 2024), 27–35.

[21] If our home institution is located on the margins of fashion’s capital (Geneva!), Paris and its luxury brands remain the school’s gold standard.

[22] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 12.

[23] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Duke University Press, 2003), 123–151.

[24] This meant conceiving of ourselves first and foremost as a collective, one that happens to design.

[25] The members are artist and designer Camille Farrah Buhler, designer Peter Wiesmann, and writer and couturière Sabrina Clavo. Together, we form the collective Horizons Glaise.

[26] Among them, fashion designer and playwright Marvin M’Toumo, cultural worker and feminist activist Elise Magnenat, and design researcher Jonas Berthod.

[27] We are still in the processing of finalizing these, but they consist of a bag and a poster.

[28] Evans, interview by Strömquist, “Challenging the Orthodoxy of Fashion from Within.”

Cydni Meredith Robertson, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at Indiana University Bloomington in Bloomington, Indiana, in the Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture, and Design, Fashion Merchandising program. Her research interests include a) women’s experiences in the global apparel supply chain and b) the preservation of culture, dress, and identity practices.

Fashion Griotte and Sankofa Approach to Costume Design

Fashion griotte Ruth E. Carter can simultaneously call forth both the past and the future, with timeless synergy, through the art of costume design. Traditional griottes/griots in West African, Senegalese, Wolof tradition express and preserve oral histories through song, poetry, and storytelling, as purposefully passed down from their ancestors. [1, 2] Carter has committed herself to authentically telling African diasporic narratives by employing creative design in clothing and accessories as her preferred medium of legacy communication. While Carter is renowned as a two-time Academy Award winner for her work in the Black Panther film franchise, Black Panther (2018) and Wakanda Forever (2022), her costuming debut in the Spike Lee joint School Daze (1988) began over 37 years of her fashioning Africentric films. From her work in motion pictures such as Malcolm X (1992), Amistad (1997), B.A.P.S. (1997), Selma (2015), Lee Daniels’ The Butler (2013), and Sinners (2025), it is evident that Carter leans on and learns from the aesthetics of the past to meaningfully connect with fashion and film consumers in the present.

In this review of Carter’s costume-in-film anthology, we explore her work through a Sankofa lens that borrows from the Akan, Ghanaian term meaning it is not taboo to go back and fetch that which is at risk of being left behind, or it is not forbidden to go into history to validate and reclaim the past, or to look to the past to inform the future. [3, 4, 5]

The Adinkra symbol of the Sankofa bird illustrates the figure as flying forward yet looking backward, symbolizing the connection of the past and the present of the African diaspora with hopes for a brighter future. [6] Much like the Sankofa bird, Carter has contributed towards her hopes of a brighter, and Blacker, future in both fashion and film for nearly four decades. In honor of the 15th anniversary of the MA Fashion Studies program at Parsons School of Design, this reflection celebrates the past 15 years of Carter’s work with abiding gratitude and ancestral reverence.

Ruth E. Carter in Academic Literature

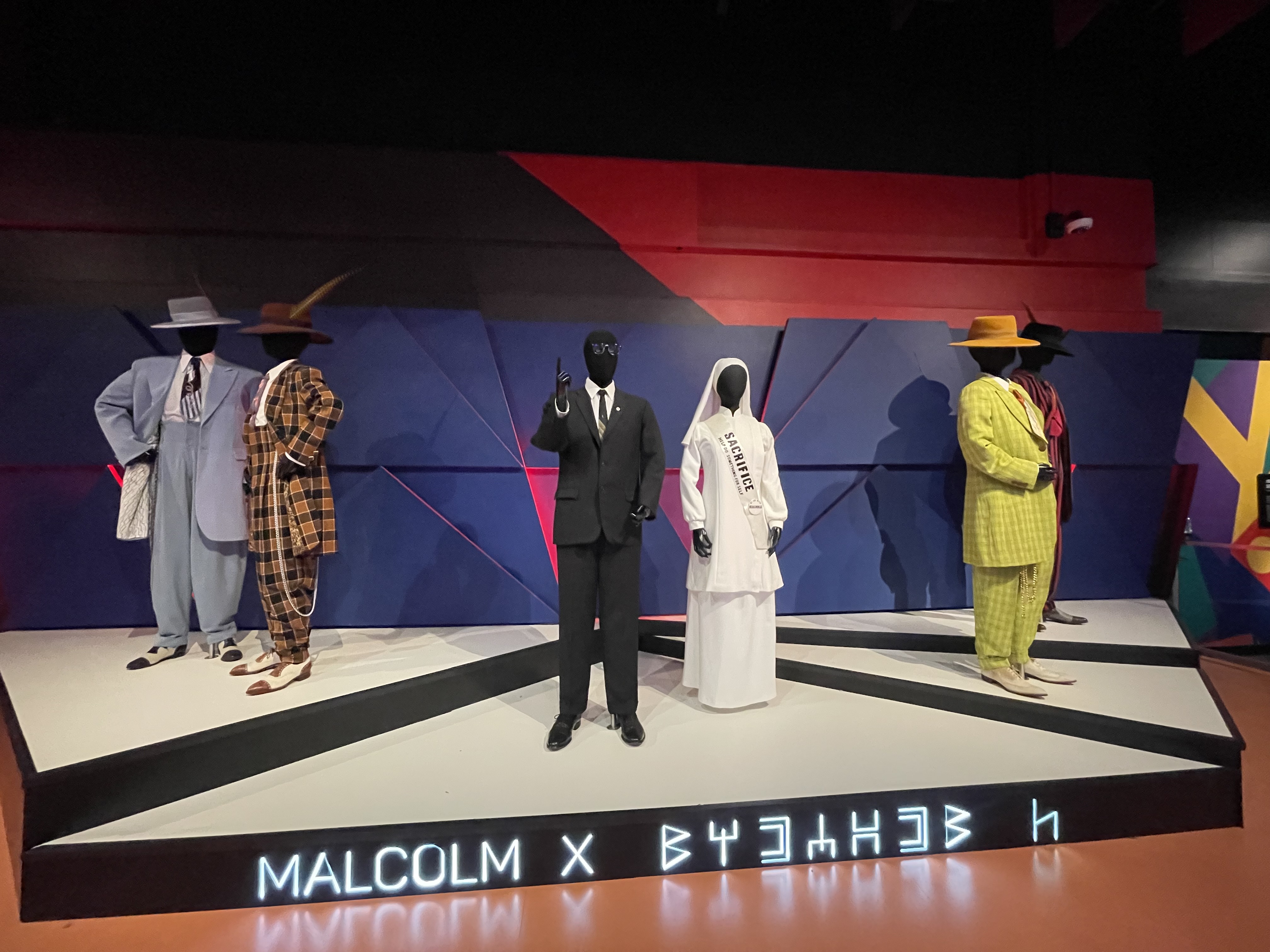

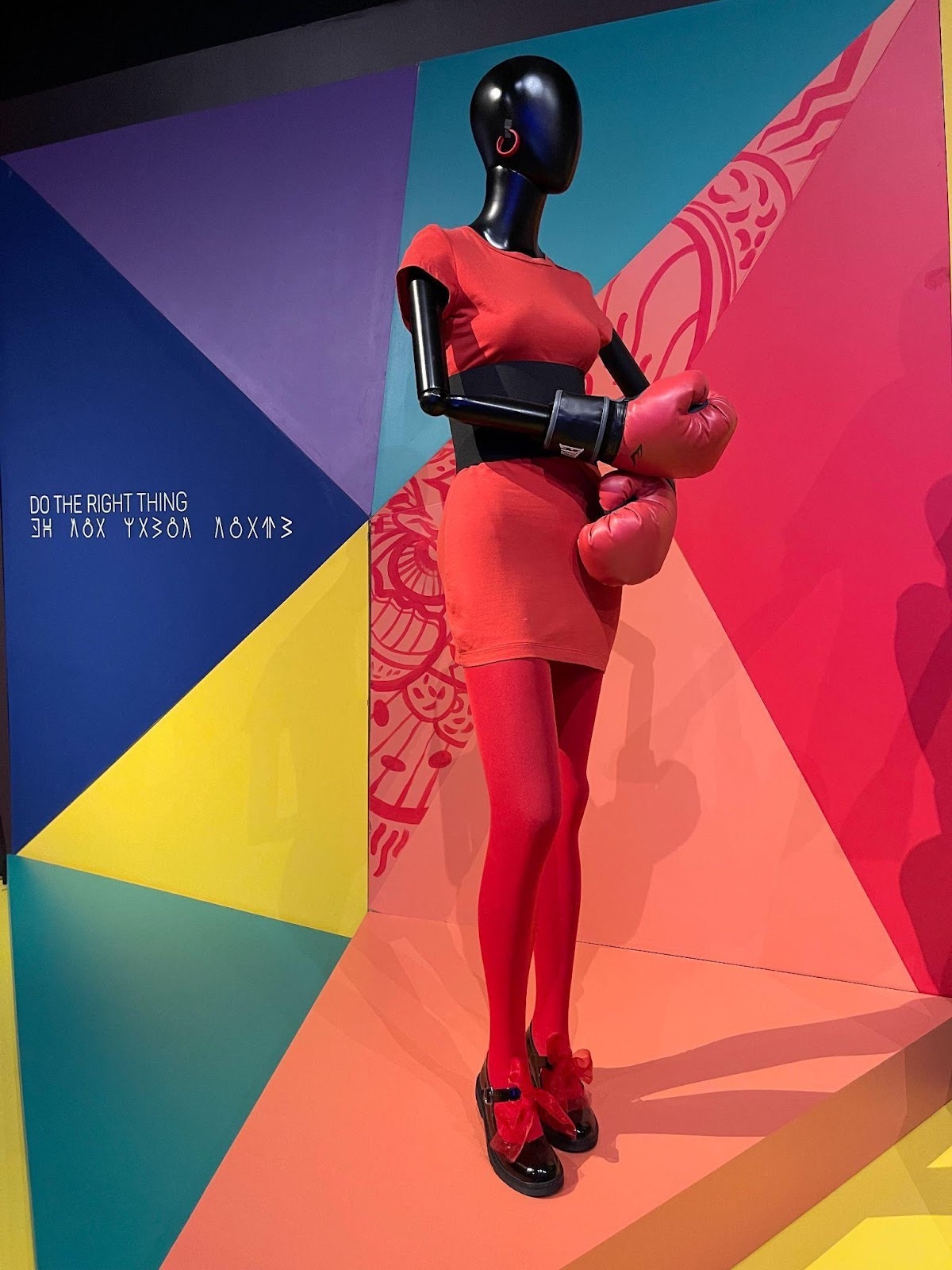

Recent fashion scholarship has examined Carter and her work by acknowledging the visual and narrative tools used to convey historical and political dress. In the film Malcolm X, Carter’s characters donned patterned, colorful, and intentionally oversized wool and silk Zoot suits which were deemed unpatriotic and culturally offensive in their time. These Zoot suits of the 1940s were also perceived negatively due to the excessive use of fabric required to construct the garments during wartime rationing and to general racialized aggression towards Mexican, Filipino, Italian, and Black American freedom of expression. [7, 8] Researchers have analyzed the complex significance of Black skin and heroic costuming from a postcolonial view as displayed in the Black Panther films. [9] Scholars have also admired the impact of historically accurate cultural dress on cinematic queens such as Wakanda’s Queen Ramonda and her array of Isicholo (see: Isicolo) South African Zulu married woman’s crowns, the majority of which were 3D-printed specifically for the film. [10] Carter’s work has also been cited in books that cater to both the academic and public audiences, including her own visual autobiography, museum exhibition reviews, doctoral dissertations, and an abundance of news articles. [11-15] The presence of Carter’s work within these vast yet connected outlets signifies the present-day relevance of her historic and futuristic art across timelines, disciplines, and audiences. To expand upon the historicism woven into Carter’s work, the following section illustrates how she intentionally places markers of time and space in the African diaspora into her costuming practices.

Top: Queen Mother Costume for the film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, designed by Ruth E. Carter. Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Top: Queen Mother Costume for the film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, designed by Ruth E. Carter. Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum. Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025. Bottom: Costuming from the film Malcolm X, designed by Ruth E. Carter.

Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Afrohistoricism - Fashion in Film that Looks Backward

Within academic literature and mainstream media, the terms Afrocentrism and Africentrism have been widely adopted. [16, 17] However, the rarely applied portmanteau Afrohistoricism now has the opportunity to be defined through the perspective of visual art and preservation of African diasporic cultural dress and identity. [18] The thread consistently woven within Carter’s work is Afrohistoricism—positive, holistic, and forward-thinking visual messaging about Black life and culture. Since 2010, Carter has designed notable nostalgic films such as Sparkle (2012), set in the 1960s Motown Detroit era, Marshall (2017), set in progressive 1940s Connecticut, and Sinners (2025), set in post-World War I 1930s Mississippi.

In The Butler, Carter personifies disco culture and the Black-is-Beautiful movement of the 1970s, with characters Cecil (Forest Whittaker) and Gloria (Oprah Winfrey) sporting matching textured black-and-white jumpsuits, inspired by a 1973 Eleganza mail-order catalog in a Frederick’s of Hollywood advertisement. [19] This costuming holds the energy of cultural revolution and self-revelation, as expressed through fashion, music, dance, and loving partnership. [20]

Top: Ruth E. Carter’s webpage, Collection, The Butler

Top: Ruth E. Carter’s webpage, Collection, The ButlerBottom: Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum. Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Yet, Carter does not limit herself to clothe-it-all-joy. In the film Selma (2015), Carter designed five dresses made of silk, cotton, taffeta, organza, and silk velvet to dress the characters representing the four little girls who passed (Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Dionne Wesley, Addie Mae Collins, and Carole Rosamond Robertson) and one survivor (Sarah Collins Rudolph) in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 15, 1963. The tragic event ignited the poem “Birmingham Sunday” (September 15, 1963) by Langston Hughes, which quotes, “Four little girls, who went to Sunday School that day, and never came back home at all - but left instead, their blood upon the wall, with spattered flesh, and bloodied Sunday dresses…”. [21] The range in Carter’s art extends beyond costume design. Her work crosses realms that connect with the human experience, bringing past pain and future hope to life through dress. These future hopes are illustrated in the following section as Carter’s influence on Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic shines in her more recent films.

Author’s Note: As I was taking in the heaviness and beauty of the five dresses in this image at the Indianapolis Children’s Museum, I heard the voice of a little girl walk by and say, “Ooh, pretty dresses!”. Those simple, yet powerful, words almost brought me to tears. While the little girl knew nothing of the significance behind these Sunday-best dresses, her innocence humanized the experience of Denise, Cynthia, Addie Mae, Carole, and Sarah. May all little girls be able to grow old and reflect on the ‘pretty dresses’ they once wore.

Top: Five little girls’ dresses for the film Selma, designed by Ruth E. Carter.

Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.Bottom: Source - Medium, “Four Little Girls, 58 Years Later,” article by: Chloe Smith. Retrieved June 2025.

“The Adinkra symbol of the Sankofa bird illustrates the figure as flying forward yet looking backward, symbolizing the connection of the past and the present of the African diaspora with hopes for a brighter future.”

Afrofuturism and The Black Fantastic - Fashion in Film that Flies Forward

When the first Black Panther film was released into theaters, fans and scholars alike erupted with excitement and critique, guided by an Afrofuturistic framework. [22, 23] Authors such as Octavia Butler, lovingly positioned as “The Mother of Afrofuturism" in literature, have researched and applied Afrofuturistic themes in their renowned work for decades. [24, 25] An extension of Afrofuturism is the concept of the Black Fantastic which is described as “works of speculative fiction that draw from history and myth to conjure new visions of African diasporic culture and identity,” and has already become popular in fashion scholarship. [26, 27] One example of Afrofuturistic dress that maintained historical accuracy and cultural relevance was the red Himba style wig. This wig utilizes shea butter and red clay to form locs that are protected from debris and harsh sun, sealed at the ends with puffs made from wool or other animal fur. This character, an Elder woman in Wakanda, wears a full red skirt and floor-length shawl trimmed in the fictional alphabet of Wakanda, inspired by Nsibidi lettering in southeastern Nigeria and designed by Hannah Beachler, who introduces the futuristic element into these pieces, allowing for a modern perspective on a historical practice. At the 2025 Costume Society of America Conference, Carter stated in her virtual keynote address that “It wasn’t enough to just research the tribes and show them in their indigenous forms, we also needed to show how they honored their ancestry, but also wanted to use modern technology through their dress.” [28]

Himba Tribal Edler Costume for the film Black Panther, designed by Ruth E. Carter,

photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Another dynamic example of Afrofuturism as expressed through dress in Black Panther were the Dora Milage warrior women costumes. The color red and detailing within their costumes were inspired by the Masai tribe in Kenya, while the warrior elements of their costumes were inspired by the Agojie, an all-women military regiment in the Dahomey Kingdom, dating back to the 17th century. Carter (2025) stated, “We wanted their armor to feel like jewelry. We wanted there to be a new way of training the eye to look at beauty under different standards.” [29] The stories told through these pieces are memorable, not just because they are aesthetically pleasing with attractive technologies and bold hues, but because they are memories made tangible in and of themselves.

A newly welcomed term, Afronowism, coined by Stephanie Dinkins, refers to “the unencumbered black mind [as] a wellspring of possibility.” [30] Much like the griottes of the past, Dinkins credits her grandmother as the primary source of inspiration behind the development of Afronowism, bringing ancestral wisdom into the modern, artfully lived experience.