by Anita Puig and Giancarlo Pazzanese

Versión en español aquí

Anita Puig (she/her). Is a Chilean Architect, and PhD Candidate in Architecture at Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. Her research has focused on Architectural Theory with a special focus on Interior spaces, textiles and gender studies. She also has published and researched cultural and spatial connections between fashion, architecture and interiors from a design and theoretical perspective.

Giancarlo Pazzanese (he/him) is a Chilean-Italian fashion lecturer and designer based in Amsterdam. He obtained a Bachelor in Arts from The Universidad Católica de Chile and has a Master's in Education & Innovation from InHolland University. Currently, he is a Senior Lecturer in Fashion Business and Fashion Design at the Amsterdam Fashion Academy and recently launched his first digital-only fashion collection on DressX.

Introduction

This is a screenshot dialogue, the solidification of an ongoing conversation. A visual and theoretical sweep of borders, limits, and disobedience. The format, apparently naïve, freely allows for highlighting some issues that have impacted the two authors regarding these debates. It also allows one to evade academic restrictions, and to express ideas freely as visual forms, consumed and disseminated. In this way, it returns to the images from the digital, the theoretical content that is behind. Screenshot dialogue is a visual game articulated with words and screen captures recording disobediences that break invisible borders established as part of conventions and social norms intercut with creators who transgress political, public, private, gender, and fashion barriers.

Jumping Borders

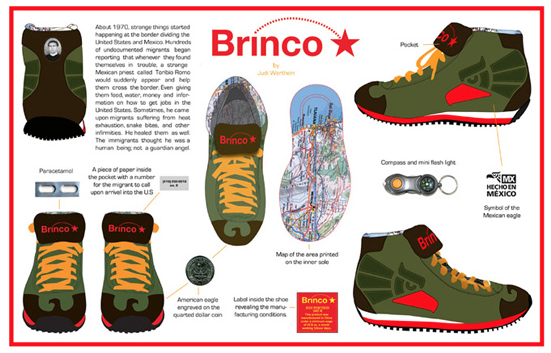

The Argentinean artist Judi Werthein made an art project where she used clothing to transgress political boundaries and demarcate borders in the production of the Brinco sneaker (2005). Her work highlights the ease of movement of consumer goods or fast fashion between different markets, in contrast to the strict rules of movement of people across borders. The sneaker was produced in China, and then given to immigrants to cross the border between Tijuana and San Diego. To facilitate the crossing, they were designed with a space to hide money, a compass and a map of the area. The garment visually represents the difficulties and dangers of migrants contrasted with a commercial product. These sneakers were also auctioned in contemporary art markets. Consumption, labor precariousness, migratory regulations, art speculation, and the search for new possibilities are questioned from an object that crosses frontiers, jumping borders of countries and markets. Why can a consumer object designed to facilitate the transit of bodies move freely, and not the people who use it, the migratory identities that give it meaning?

Judy Werthein, Brinco (2005). Footwear design features. Source: www.globalcorporacy.com

The Brinco sneakers is a good work to start thinking of fashion, borders and

disobedience. The idea of putting in tension the circulation of goods, people and

markets as art project is brilliant. I saw it at the ‘On Mobility’ group show in De Appel,

Amsterdam in 2006. [1] The money made from the sales was funneled back into supporting the ongoing

distribution of sneakers to undocumented migrants, and a donation from the sales was

made to the Casa del Migrante, a migrant support organization. [2]

The Brinco sneakers is a good work to start thinking of fashion, borders and

disobedience. The idea of putting in tension the circulation of goods, people and

markets as art project is brilliant. I saw it at the ‘On Mobility’ group show in De Appel,

Amsterdam in 2006. [1] The money made from the sales was funneled back into supporting the ongoing

distribution of sneakers to undocumented migrants, and a donation from the sales was

made to the Casa del Migrante, a migrant support organization. [2]

Rethinking Borders

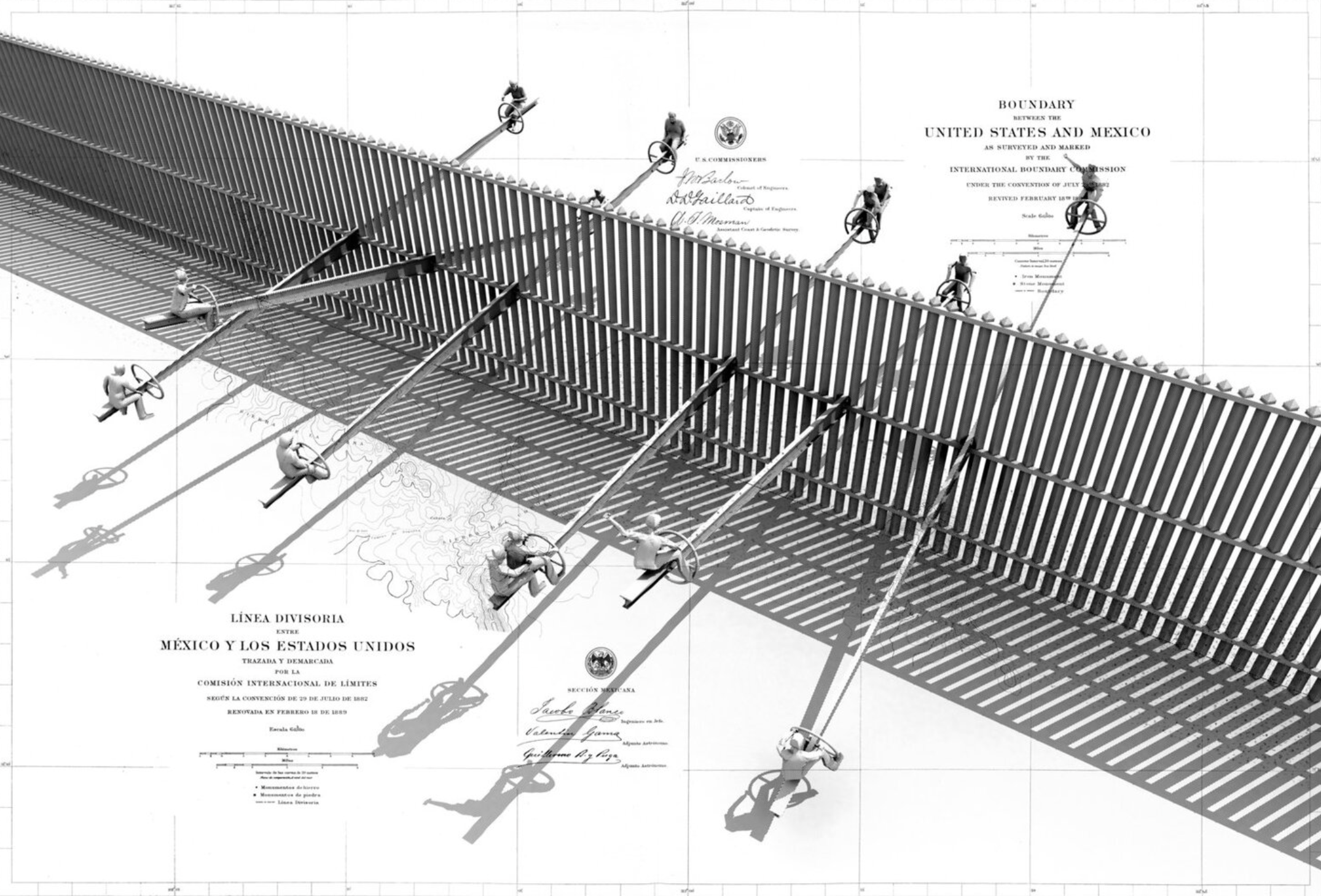

During the Trump administration, the wall as a border between the United States and Mexico was reaffirmed as policy. The extension of this barrier was erected as a questionable architectural competition in 2016. The impossibility of connecting the reality of migrants with a solid, divisive and forced structure raised questions about the intention of designing and awarding that space. The erected wall has also allowed the reflection of counterparts such as the Mexican architect Rael San Fratello. The Teeter-totter Wall located on the fence itself consisted of the design of seesaws in bright pink, proposing that the inhabitants give life to an inert space through the action of their weight and body — a temporary balance and union between the two sides. The action of use separates the political condition of the borders from the reality of the bodies that inhabit those places, demonstrating the role of design in the critique of power structures, giving back to the communities their right to a protected territory without political restrictions.

The controversy of the contest, broadcast by Archdaily, sparked the annoyance of many, and the platform repeatedly corrected the content. Although the organizer Third Mind Foundation claimed to be politically neutral, can you really be neutral in the face of these questionable actions? [3]

Borderline Bodies

The immense number of deaths at the borders as a result of forced migrations along with the increase of homeless people has mobilized designers to remedy the precariousness of these dispossessed groups. Bas Timmers designed his first Sheltersuit in 2016, a jacket that transforms into a waterproof sleeping bag made from recycled tents to mitigate the conditions of those sleeping on the streets. This garment continued to be replicated in her studio in the Netherlands, thanks to the work of Syrian volunteers, who in return received help in their integration process and assistance in finding housing. So also designer Angela Luna designed in 2016 unisex garments for refugees that feature reflective fabrics, harnesses for carrying children, floating collars and reversible lining to reflect light. Her most notorious garment is a jacket that transforms into a tent. In this way, Angela and Bas have found a way to transform the fashion production chain based on luxury and exclusion into social practice. The struggles become tangible, they enter into a non-profit productive system and criticism is communicated by making its clothing. Politics is confronted and the basic embodied elements appear — shelter and clothing as protection.

Professor Helen Storey has operated in reverse. Instead of recycling materials to produce garments, she designed the “Dress of Our Times” from a decommissioned tent belonging to the UN Refugee Agency. The dress has been exhibited as a tool to discuss the massive migration of people due to the effects of climate change. This project evolved into Zaatari Action when Helen visited the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan to create opportunities for reciprocal knowledge exchange and investigate alternative narratives coming from the refugee camps themselves as a designer in residence. Since 2016, Helen has implemented over 15 projects with women from Syria which aim to transform the asylum center into an empowered and autonomous community through education and management consulting. Helen remains vigilant in not imposing marketing techniques and maintaining the identity of the creators by producing design and quality objects. The long-term vision is to transform the asylum into a self-sustaining and autonomous community where the refugee changes his status from passive waiting on the margins of a society that invalidates him to activating his community with a new sense of agency. This is the difference between empowering refugees and taking over their status.

Bas Timmers. Sheltersuit (2016). Source: www.sheltersuit.com

Angela Luna. The Trench (2016). Source: www.adiff.com

Angela Luna. The Trench (2016). Source: www.adiff.comAngela Luna has developed a clothing line by upcycling discarded material and has

achieved with its sale the donation of thousands of jackets, as well as paying salaries to

more than 70 thousand Afghan refugees. [5]

Helen Storey. Dress For Our Time at UN Geneva. Source: www.dress4ourtime.org

Helen Storey. Dress For Our Time at UN Geneva. Source: www.dress4ourtime.orgHelen Storey’s work makes it possible to think about how to interact with refugees

collaboratively. It is necessary to identify the people involved, to value their work, their

context and the possibilities of mutual education and cooperation. [4]

Gender Borders

Janine Antoni’s work moves us from physical borders to gender borders. She explores the concept of identity through the body, its actions, and the context that codifies it. In Mom and Dad, she explores gender roles and the relationship between clothing, makeup, body and art with three anniversary photographs of Antoni’s parents in which they are made up and dressed to resemble each other. The artist questions the relationship between the feminine use of makeup and its use as a tool for art. Janine makes her own family portrait and disobeys the established conventions for father and mother figures. She deconstructs and reconstructs her parents in the other’s body. She provokes a fusion of their identities, and the dissolution of personal limits where both form the same parental entity. On the other hand, she reflects on the normalized expressions and appearances for each gender separately.

Janine Antoni. Mom and Dad (1994). Source: www.janineantoni.net

Janine Antoni. Mom and Dad (1994). Source: www.janineantoni.netVirtual Borders

The possibilities for expressing and exploring feminine, trans, queer and fluid identities are expanding where physical and virtual experiences collide. Artificial intelligence, metahumans and virtual twins are changing our perception of the limits of the body. Glitch Goddess, by artist Marjan Moghaddam, is an augmented reality series in which a virtual female avatar is constantly mutating between different bodies and states, changing age, size, texture and shape. This iterative work dismantles the idea that there is a singular way, based on historical conventions, of representing women. It raises the question of gender inclusion and diverse representation in the media universe and metaverse. We need to expand what gender inclusivity means in the era of digital transformation to avoid reinforcing gender stereotypes, such as the over-sexualization of female avatars in the gaming industry. Thus, it is imperative to consider the possibility of multiple gender expressions in physical and virtual life.

Marjan Moghaddam. Frame from Glitch Goddess. Source: www.instagram.com/marjan_moghaddam_artist

Marjan Moghaddam. Frame from Glitch Goddess. Source: www.instagram.com/marjan_moghaddam_artistThe Broad Border

This unfinished conversation drifts between the broad meanings of edges as limits, from which bodies and their representations seem to overflow. The object of clothing that moves through other limits dislocated by a utilitarian object; the wall blurred by the body and the territory measured from communities and not politics; the clothing and the protective function that does not recognize political borders but uses; virtual bodies that are redrawn by their temporary representation outside conventions are just some cases to start this extensive debate... always updating.

Notes: A Visual Script on Borders and Borderline Garments

[1] On Mobility. 2006. De Appel. Accessed 18 September 2022. deappel.nl/en/archive/entities/1193-judi-werthein

[2] CLOSEUP Judi Werthein, Brinco, inSite_05. Insite. Accessed 18 September 2022. insiteart.org/multimedia/closeup-judi-werthein-brinco-insite-05

[3] Call for Entries: Building the Border Wall? 04 Mar 2016. ArchDaily. Accessed 18 Sep 2022. archdaily.com/783550/call-for-entries-building-the-border-wall ISSN 0719-8884

[4] Zataari Action. London College of Fashion. Accessed 18 September 2022. sustainable-fashion.com/zaatari-action

[5] About. Adiff. Accessed 18 September 2022. adiff.com/pages/about

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics