by Lucia Cuba

Versión en castellano aquí

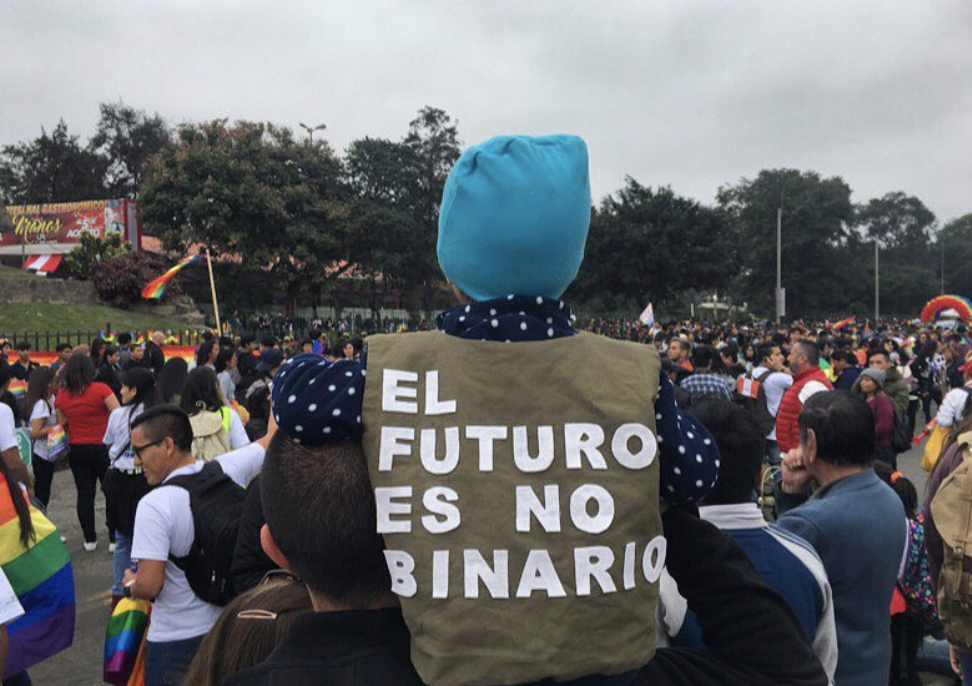

Figure 1. Lima, July 1, 2018. “The Future is non-Binary.” LBGT Pride March.

Figure 1. Lima, July 1, 2018. “The Future is non-Binary.” LBGT Pride March.

Lucia Cuba approaches fashion, textiles, and the exploration of wearable forms as performative and political devices. As a fashion designer and a scholar, Cuba is interested in issues of gender, biopolitics, and global fashion practices. She has developed projects related to health, activism, education, and the study of non-Western fashion systems. She currently works as an independent designer, as the Director of the MFA Fashion Design and Society, and Professor of Fashion Design and Social Justice, at The New School University. [luciacuba.com].

Can wearable objects spark critical conversations? Can textile resources (such as fabrics, sewing techniques, or clothing patterns) be appropriated by all, and not just those who are professionally involved with fashion design? Beyond public space, what other contexts can objects designed for protest occupy?

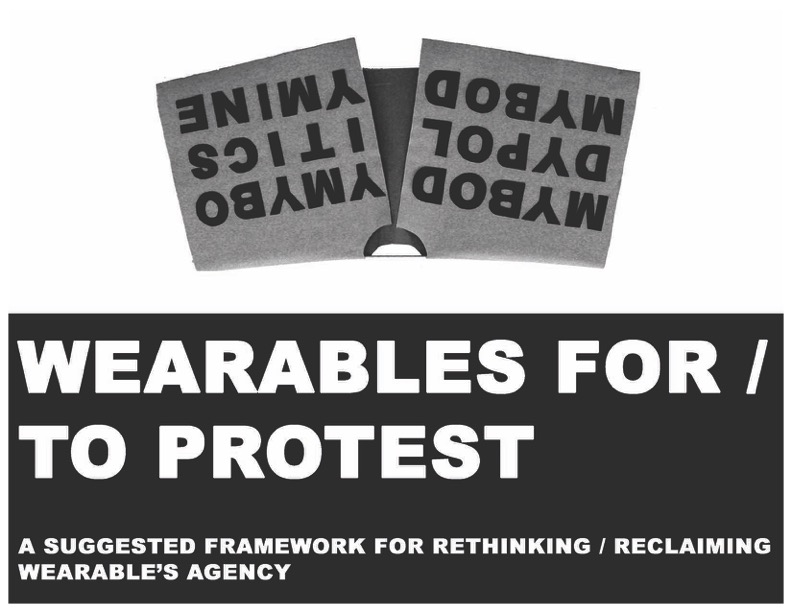

These were some of the questions that prompted the development of the project “Wearables for/to protest” (WFTP), an exercise of construction and representation of personal and social events transformed into functional and wearable objects. The project is activated through wearable textile creations, on the body of those who wear them, and through workshops where participants engage in multiple processes related to the construction of these objects, as well as conversations about social and personal issues.

Conceived as political devices, these wearable objects record acts of individual protest against ideas and institutions and in turn, serve as tools to generate a reaction from those who confront them.[1] This series proposes that political creation and mobilization can take place in daily life, through individual acts, and in dialogue with what one wants to transform or actively resist.

WFTP originated at the end of 2016, in the context of the presidential elections in the United States. That year, the potential election of Donald J. Trump sparked multiple conversations about sexual and reproductive rights and the right to abortion among United States citizens. This was a period marked by activism and popular protests that triggered conversations about social justice and citizen participation in defining a public agenda.

These were some of the questions that prompted the development of the project “Wearables for/to protest” (WFTP), an exercise of construction and representation of personal and social events transformed into functional and wearable objects. The project is activated through wearable textile creations, on the body of those who wear them, and through workshops where participants engage in multiple processes related to the construction of these objects, as well as conversations about social and personal issues.

Conceived as political devices, these wearable objects record acts of individual protest against ideas and institutions and in turn, serve as tools to generate a reaction from those who confront them.[1] This series proposes that political creation and mobilization can take place in daily life, through individual acts, and in dialogue with what one wants to transform or actively resist.

WFTP originated at the end of 2016, in the context of the presidential elections in the United States. That year, the potential election of Donald J. Trump sparked multiple conversations about sexual and reproductive rights and the right to abortion among United States citizens. This was a period marked by activism and popular protests that triggered conversations about social justice and citizen participation in defining a public agenda.

Figure 2. March 24, 2018. Archive documentation, heading to the “March for our Lives,” in New York City.

Figure 2. March 24, 2018. Archive documentation, heading to the “March for our Lives,” in New York City.During this time, the use of expressive resources that could be seen as forms for protest, such as paper or cardboard posters, began to appear not only in public spaces, but also in private spaces (houses, educational centers, and various institutions).[2] Expressive resources are, as Scribano mentions, textual objects that allow the definition, construction, and social distribution of the meaning of an action. In this context, the expressive resources went beyond the traditional forms of protest, and expanded new meanings and impacts of protesting. A good example is the “pussy hat,” a pink-knitted hat that was worn by most participants of the massive Women’s March that took place on January 21, 2017 — President Donald Trump's first full day in office — in which more than 500,000 people gathered to advocate for gender equality. The “pussy hat” became much more than a hat. For months to come, the hat would stand as a symbol of advocacy for women’s rights in the United States. It also became recognized as the result of an open-source system where participants would learn how to knit, sew and make a “pussy hat” by downloading patterns, participating in forums and learning from tutorials. The goal was for participants to make these hats to wear during the march or to send them to the organizers to distribute to those participating.

WFTP proposes a strategy for the generation of expressive resources, but with the intention of situating itself beyond an idea of fashion for protest, which Thurman defines as “a show of solidarity towards a social cause.”[3] From a critical perspective, WFTP conceives of the wearable resource as a political device that is activated not only in public space but also in private spaces (home, school, or workplace) and that acquires meaning and greater symbolic and personal value by being created by those who aim to use it.

The appropriation of creative processes (the actual creation and production of the object) that WFTP proposes through an activation workshop allows people to recognize their agency not only in the process of developing expressive resources but also in the understanding and definition of a social issue that they want to address, approaching this through the critical and physical making of the message that appears in the object. WFTP provides the opportunity for people to approach textiles as a critical medium and tool, without necessarily having advanced technical knowledge (textile appropriation resources and techniques such as sewing, weaving, embroidery, printing, etc.). [4]

First Activations

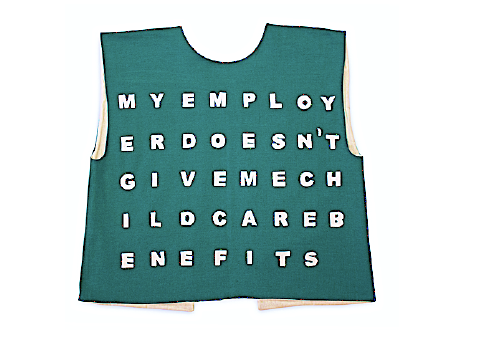

Between 2016 and 2018, two ways of approaching the project emerged. In the first approach, I developed wearables from my personal experience in relation to issues such as migration, motherhood, and work environment (See figures 3 and 4). This process took place during an artist residency at the Museum of Arts and Design, BRIC Arts Media Center, and the Center for Textile Arts in New York.

WFTP proposes a strategy for the generation of expressive resources, but with the intention of situating itself beyond an idea of fashion for protest, which Thurman defines as “a show of solidarity towards a social cause.”[3] From a critical perspective, WFTP conceives of the wearable resource as a political device that is activated not only in public space but also in private spaces (home, school, or workplace) and that acquires meaning and greater symbolic and personal value by being created by those who aim to use it.

The appropriation of creative processes (the actual creation and production of the object) that WFTP proposes through an activation workshop allows people to recognize their agency not only in the process of developing expressive resources but also in the understanding and definition of a social issue that they want to address, approaching this through the critical and physical making of the message that appears in the object. WFTP provides the opportunity for people to approach textiles as a critical medium and tool, without necessarily having advanced technical knowledge (textile appropriation resources and techniques such as sewing, weaving, embroidery, printing, etc.). [4]

First Activations

Between 2016 and 2018, two ways of approaching the project emerged. In the first approach, I developed wearables from my personal experience in relation to issues such as migration, motherhood, and work environment (See figures 3 and 4). This process took place during an artist residency at the Museum of Arts and Design, BRIC Arts Media Center, and the Center for Textile Arts in New York.

Figure 3. My employer doesn't give me childcare benefits, 2016. Open tunic in cotton, with letters in 100% wool felt.

Figure 4. I abortion, 2017. Open tunic. Textiles: neoprene, wool felt, cotton. Technique: sewing, stencil.

“Conceived as political devices, these wearable objects record acts of individual protest against ideas and institutions and in turn, serve as tools to generate a reaction from those who confront them.”

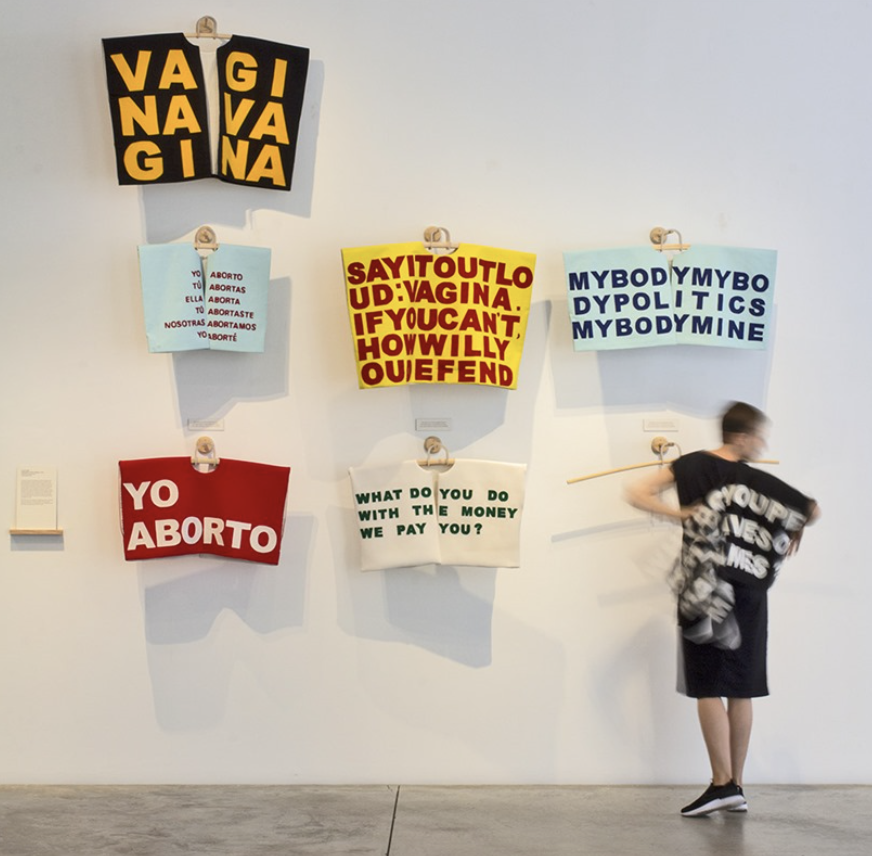

As a second approach, wearables were developed as part of workshops, where the facilitation of wearable-making processes allowed for participants to reflect upon personal and social issues they had experienced. These sessions took place at the Textile Arts Center and at Pioneer Works, two cultural spaces in New York. Later, in 2018 and 2019, two additional workshops were held as part of the Disobedient Fashion gathering organized by the Chilean collective Malvestidas (Poorly Dressed), in The Santiago Museum of Contemporary Art, and in the context of the exhibition “In the Historical Present” at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery - Sheila C. Johnson Design Center in New York.

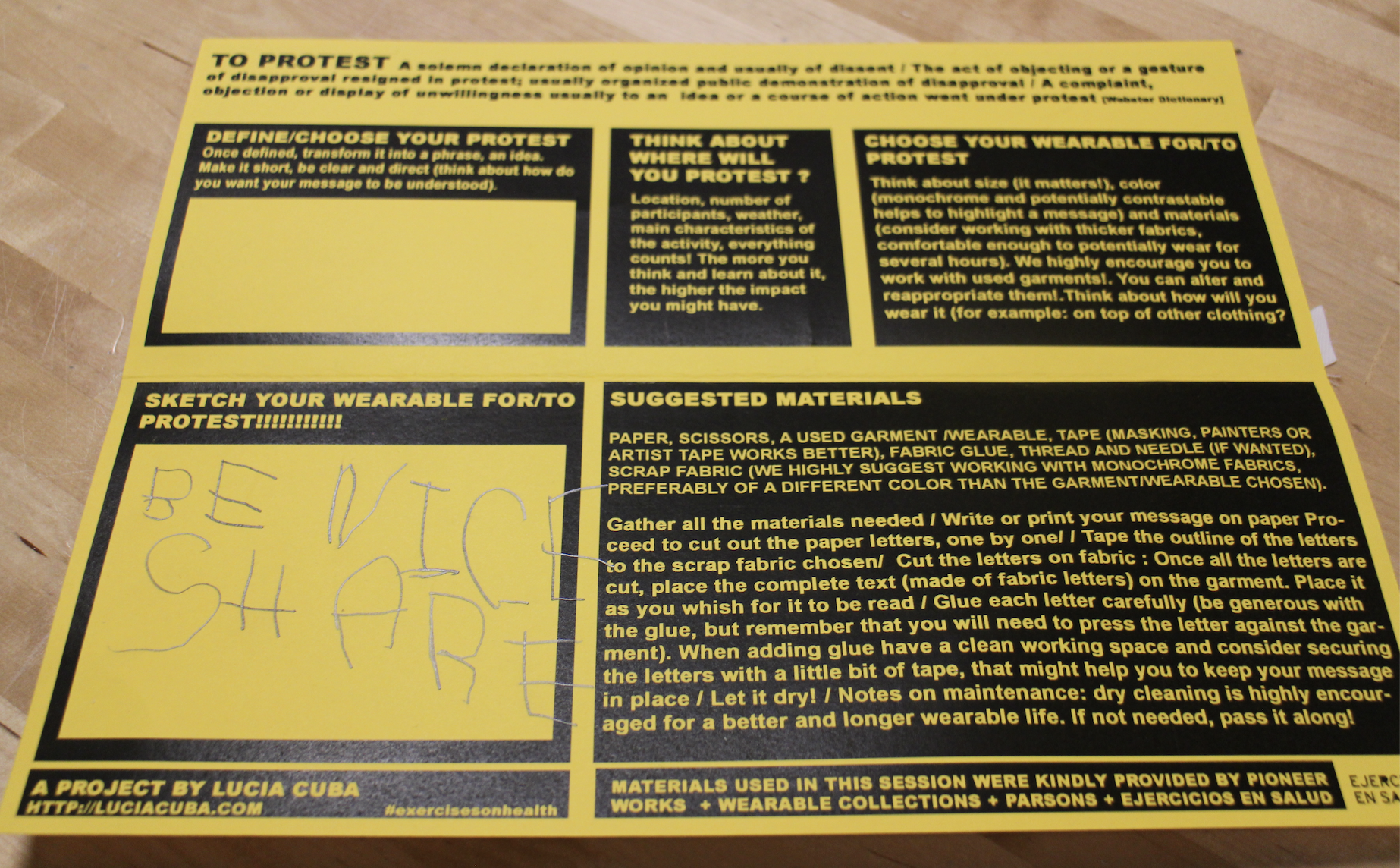

The session at Pioneer Works was open to a mixed-age audience, which allowed for a broader conversation. For example, figure 5 shows a wearable (a piece of clothing with cut-off sleeves) that reads “Puppy.” This was the result of a conversation about wearables as a means of conveying an opinion. The creator of the wearable, self-identified as a 6-year-old girl, mentioned that she wanted to adopt a dog but that this was a difficult conversation at home. Therefore, she decided to highlight the word Puppy on her garment to “make her parents think about it.” In this case, the expressive resource allows the participant to activate a personal conversation around a desire, a demand that requires a conversation with her family. On the other hand, figure 6 shows a printed guide to make a wearable for/to protest. The image shows a text written by a 7-year-old participant who chose the phrase “be nice share” to place on a wearable so that people could read it and, as mentioned by the participant, “be more friendly and supportive.”

The session at Pioneer Works was open to a mixed-age audience, which allowed for a broader conversation. For example, figure 5 shows a wearable (a piece of clothing with cut-off sleeves) that reads “Puppy.” This was the result of a conversation about wearables as a means of conveying an opinion. The creator of the wearable, self-identified as a 6-year-old girl, mentioned that she wanted to adopt a dog but that this was a difficult conversation at home. Therefore, she decided to highlight the word Puppy on her garment to “make her parents think about it.” In this case, the expressive resource allows the participant to activate a personal conversation around a desire, a demand that requires a conversation with her family. On the other hand, figure 6 shows a printed guide to make a wearable for/to protest. The image shows a text written by a 7-year-old participant who chose the phrase “be nice share” to place on a wearable so that people could read it and, as mentioned by the participant, “be more friendly and supportive.”

Figure 5 and 6. November 13, 2017. Archive documentation of the “Vestibles para/por la protesta” workshop as part of the “Fact Crafts / Family Sundays” series at the Pioneer Works cultural center in New York City.

Figure 7 and 8. The two images below belong to other wearables developed by workshop participants, both of which activate phrases linked to the “Me too” social movement, which consisted of multiple conversations and accusations about systemic sexual abuse of women. November 13, 2017. Archive documentation of the “Vestibles para/por la protesta” workshop as part of the “Fact Crafts/Family Sundays” series at the Pioneer Works cultural center in New York City.

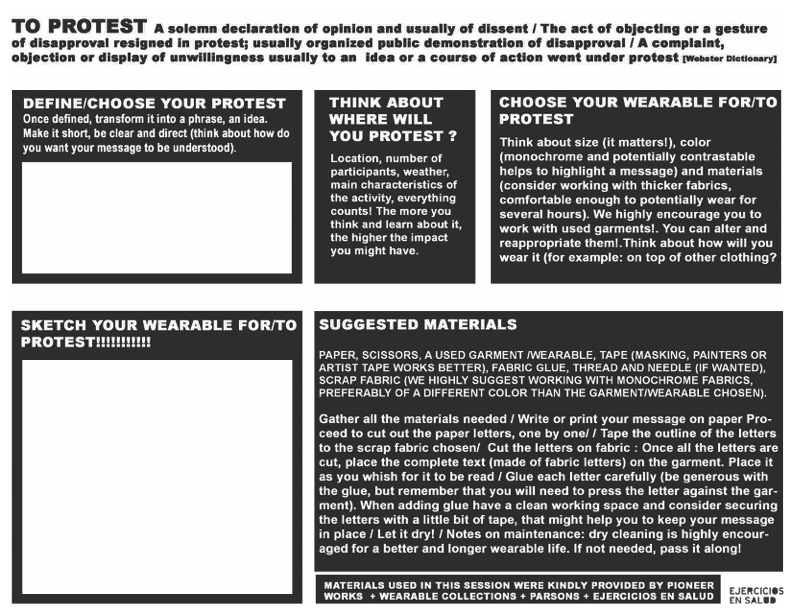

The printed guides were conceived as educational tools to facilitate the process of creating these expressive resources. Initially aimed at adults and readers, they are currently being rethought to target non-readers of various ages.

The aim of these educational resources is to teach basic stencil techniques (a technique for stamping figures), appliqué (applying cuts from one material to another), and typographic techniques (such as contrasting colors and sizes). In addition, key questions are included to guide reflection on the theme that is to be represented in the wearable. Workshop activations adapt to different contexts, including where the session is held, what infrastructure is in place, and what materials are available.

Figure 11. July - October 2019. WFTP installed as part of the exhibition “In the Historical Present” at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery-Sheila C. Johnson Design Center in New York. Wearables installed to be activated (dressed) by sample participants.

Figure 11. July - October 2019. WFTP installed as part of the exhibition “In the Historical Present” at the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Gallery-Sheila C. Johnson Design Center in New York. Wearables installed to be activated (dressed) by sample participants.

The different activations of WFTP allow the project to explore the role of wearable objects in public and private acts of protest, and the possibility of proposing alternative ways of expressing a critical position explicitly.

Beyond the identity garment (the one that signifies our role in a specific community), WFTP offers the possibility of considering the wearable resource as media, a means and as an agent. The pieces are intended to be made and appropriated by the users, worn and reworn, shared, and given away. They convey both self and social reflection. They prompt and question the possibilities of users to create wearable forms: to explore their power and to activate these with intention. By recognizing their agency, wearers and wearables can be part of a strategy that transforms the relationship between object, subject, and society.

Notes: Between the Public and Private

[1] Michel Foucault, quoted in Dittus, R. (2019). The Notion of “Device” in Giorgio Agamben. Advances in Applied Sociology, 9, 47-59. doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2019.91004

[2] Scribano in Cervio, Ana Lucía , & Guzmán Romero, Anvy (2017). Los recursos expresivos en la protesta social. El caso del “Acampe Villero” en Buenos Aires. Iberoforum. Revista de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Iberoamericana, XII(23),36-64.[Fecha de consulta 22 de Febrero de 2022]. ISSN: . Disponible en: redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=211053027002

[3] Thurman, Judith. (2021). What counts as protest fashion? .[Fecha de consulta 13 de Marzo del 2022] . Disponible en: newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-counts-as-protest-fashion

[4] In this text, textile is understood as that which can refer to a fabric, garment or technique linked to textile practices (weaving, embroidery, etc.).

Additional References

Gill, Alison & Mellick Lopes, Abby. (2011). On Wearing: A Critical Framework for Valuing Design's Already Made. Design and Culture. 3. 307-327.

Valle-Noronha, Julia. (2017). On the agency of clothes: surprise as a tool towards stronger engagements.

Marcha del Orgullo LGBTI en Lima, Peru. Mayor información aquí: wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcha_del_Orgullo_LGBT_de_Lima

Para mayor información sobre el movimiento Me Too en los Estados Unidos: metoomvmt.org/

Beyond the identity garment (the one that signifies our role in a specific community), WFTP offers the possibility of considering the wearable resource as media, a means and as an agent. The pieces are intended to be made and appropriated by the users, worn and reworn, shared, and given away. They convey both self and social reflection. They prompt and question the possibilities of users to create wearable forms: to explore their power and to activate these with intention. By recognizing their agency, wearers and wearables can be part of a strategy that transforms the relationship between object, subject, and society.

Notes: Between the Public and Private

[1] Michel Foucault, quoted in Dittus, R. (2019). The Notion of “Device” in Giorgio Agamben. Advances in Applied Sociology, 9, 47-59. doi.org/10.4236/aasoci.2019.91004

[2] Scribano in Cervio, Ana Lucía , & Guzmán Romero, Anvy (2017). Los recursos expresivos en la protesta social. El caso del “Acampe Villero” en Buenos Aires. Iberoforum. Revista de Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad Iberoamericana, XII(23),36-64.[Fecha de consulta 22 de Febrero de 2022]. ISSN: . Disponible en: redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=211053027002

[3] Thurman, Judith. (2021). What counts as protest fashion? .[Fecha de consulta 13 de Marzo del 2022] . Disponible en: newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/what-counts-as-protest-fashion

[4] In this text, textile is understood as that which can refer to a fabric, garment or technique linked to textile practices (weaving, embroidery, etc.).

Additional References

Gill, Alison & Mellick Lopes, Abby. (2011). On Wearing: A Critical Framework for Valuing Design's Already Made. Design and Culture. 3. 307-327.

Valle-Noronha, Julia. (2017). On the agency of clothes: surprise as a tool towards stronger engagements.

Marcha del Orgullo LGBTI en Lima, Peru. Mayor información aquí: wikipedia.org/wiki/Marcha_del_Orgullo_LGBT_de_Lima

Para mayor información sobre el movimiento Me Too en los Estados Unidos: metoomvmt.org/

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics