Tetyana Solovey is an experienced editor, journalist, communications professional and educator working on the nexus of fashion & design, curatorship and sustainability advocacy. Worked as an editor-in-Chief at Buro. independent online media (2020-2022) and Fashion features & Jewelry and Sustainability Editor at Vogue Ukraine (2012-2020). Chevening Alumni 2022. Since 2023 a PhD student at the School of Social Sciences at the University of Manchester.

The war in Ukraine began on the second day of Milan Women’s Fashion Week, Autumn-Winter 2022. Fashion week is highly focused on bodies: models, agents, and guests not only demonstrate the latest fashions but also create an atmosphere of genuine excitement and embodied amusement, as expressed in their poses, their gestures, their hugs and kisses. This time, the fashion media landscape became political and violent: a disturbing mix of images featuring both fashionable and wounded bodies.

When the war started in my country, I observed it through the fashion media framework. I spent seven years at Vogue Ukraine in the position of Fashion Features & Jewellery and Sustainability Editor. During the last five years, I advocated for sustainability in fashion, being truly convinced that it could be a platform to catalyze change by setting an example. I expected to see a reaction in the industry to such an ethically and ecologically challenging event as a war. As a Goldsmiths, University of London student, I was analyzing how the development of new forms of media influenced the principles of warfare.

Walter Benjamin described the effectiveness of the aestheticization of politics, referencing the mobilizing of masses following Nazi ideology, which happened alongside the development of moving images technology – the cinema. In particular, he described how the cinema’s power to transform everything into spectacle was used to dominate the masses. [1] Jean Baudrillard went even further, virtually questioning the reality of the Gulf War. He argued that the broadcasting of the Gulf War on TV radically changed its essential meaning (the opposition between friend and enemy, and the end goal of conquest or domination), making it possible for him to argue the simulated nature of the war in “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place.” [2] It is clear that – at least in its early days – the war in Ukraine, framed in the media as “the most online war ever,” did not take place exclusively on the battlefield. It was fought, communicated, and generally experienced under the giant influence of social media, where the affective power of war was spreading in a viral flow of contagious images and messages.

My master's dissertation was devoted to observing critically what I was already following. I studied the luxury industry's reaction to the war in Ukraine through the lens of affect theory. My findings led to the conclusion that the tension that emerged in social media plays a major role not only in spreading awareness about the war but in changing luxury and fashion brands' public responses to it. Moreover, the collective call for businesses to act morally and take the right side has shaped brands' and corporations’ responses.

In my research, I examined the narratives produced by brands as their responses to the war within the broader media landscape. Data were gathered from five corporate and 12 brand social media accounts, which were selected from a larger scoop of 10 corporate and 87 brand accounts in the luxury and mass market and examined with a textual-analysis approach. The data were gathered during Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks. This time frame was selected because the radical shift in communications in business took place within 12 days, from 24 February through 8 March.

What follows is an edited version of my favorite part of the dissertation.

The fashion and luxury industry remained mostly silent in communicating its position on the war in Ukraine for almost a week. On 2-3 March, the biggest luxury sector players, French conglomerates LVMH and Kering as well as independent companies such as Chanel and Prada, almost simultaneously released public statements regarding their concerns about the war in Ukraine, pledging to donate to humanitarian missions on the ground. This aligned with their temporary suspension of business operations with Russia, caused by DHL and FedEx's decision to stop shipments to that area. The loudest voice in the industry belonged to Demna Gvasalia, Balenciaga’s Georgia-born creative director. The most awaited show on the Paris schedule, on 6 March, started with the words of Ukrainian poet Oleksander Oles: “Live long, Ukraine, live for your beauty! For strength, truth, and liberty!” The poem was read by Demna himself. T-shirts in the color of the Ukrainian flag were distributed as exclusive merch to guests; despite having been arranged well before the beginning of the war, the entire show setting became purposely reminiscent of refugees walking in stormy winter weather; invitations to Russian industry players were canceled. There wasn't any doubt what the brand stood for, and this position was skillfully delivered with maximum media effect through a network of friendly, highly visible media accounts before and after the show.

Still, customers' expectations for the industry to manifest a strong moral position were not met, probably because most luxury brands limited their communications to publishing messages of support and reporting the amount of their donations on their websites, without repeating this messaging on social media, making it less visible to customers and followers who don't check corporate news sections. Interestingly, nobody was surprised that such an expectation was there in the first place.

The war in Ukraine was a clear signal of change in neoliberal society, where key market players had their agency. The imperative to act ethically exists for corporations as well as customers. Businesses are expected to act responsibly towards people and wildlife and to contribute to solving social problems, much like government and non-governmental organizations (should) do. Customers strive to demonstrate commitment to ethical values in their consumer behavior; moreover, they place themselves in charge of monitoring brands' commitment to ethical values, constantly challenging them by asking #WhoMadeMyClothes or demanding that they react to ongoing social crises by supporting #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, or #StandWithUkraine.

Sociologist Avram Arvidsson named this development in society “ethical capitalism” [3] and claimed that its development is enhanced by communication technologies. According to Arvidsson, the value of business is related to ethics. He interprets the latter in the Aristotelian sense as a state of social “virtuous coexistence.” [3] He claims that the “ethical surplus” [3] determines the success of brands and describes it as a two-sided process of brand management. It is related both to the ability to develop affective attachments with customers, which motivate and inspire them to participate in brand value creation, and to the ability to attune to common contributions to society, to “support a common sense of purpose and direction that operates independently of command or monetary rewards” [3]. Importantly, ethical surplus becomes an obvious measure of public affection for the brand.

Predictably, fashion mirrored this market tendency towards “moralization” [4] and “responsibilization.” [5] For more than five years, the industry has claimed to put values at the core of its business; people and the planet are constantly in its operational focus and communications. Companies such as Pangaia, and designers such as Gabriela Hearst, owe their success almost exclusively to their passionate commitment to sustainable development. The war, which affects human life as severely as global warming, was expected to be a matter of great concern for luxury brands, too.

In their statements regarding the war in Ukraine, luxury brands developed a discourse with moral agency, taking responsibility for solving social issues alongside government and non-governmental organizations. Relying on governments’ diplomatic efforts, they merged their own efforts with the most well-known charities and NGOs, such as the UN Refugee Agency or UNICEF, illustrating how businesses are expected to be accountable for participating in social life. Even more, it shows how brands demonstrate their ability to attune to media flow around an event created by their demanding followers. The use of the word “war” in statements is a good example.

The need to describe precisely the events in Ukraine was behind some tension on social media in the first days of the war. One of the most frequent accusations on social media was leveled at those who used an indirect description, such as “crisis” or “tragedy,” which effectively deflected blame from Russia as a country-aggressor; the call for peace and against war was perceived as a camouflaged message to the aggressor to surrender.

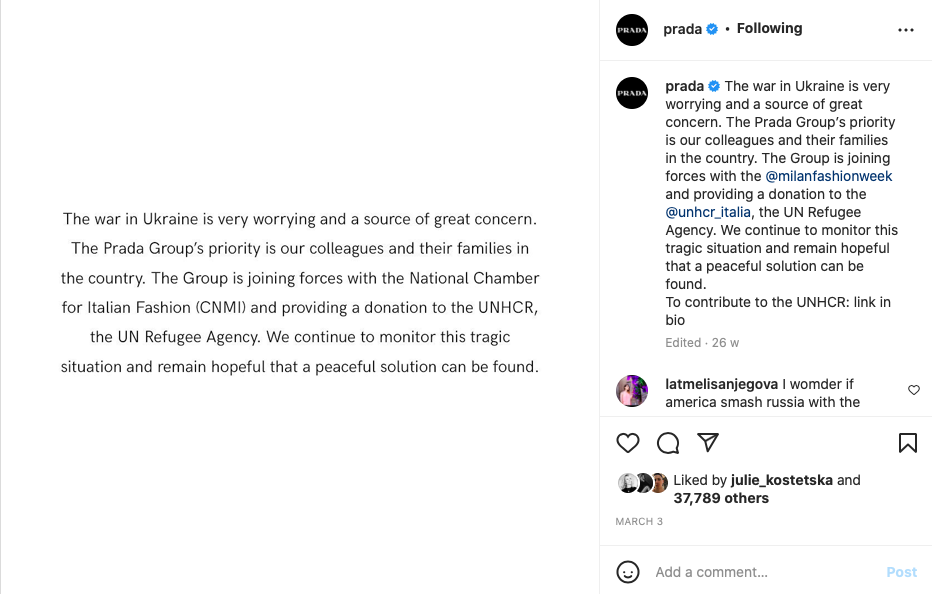

Prada exemplifies the tendency of luxury reactions. A screenshot of a deleted Instagram post shows that they used “crisis” in their initial statement, while the statement now on the brand's account has the word “war.” In a week, brands gradually moved from using descriptive words such as “crisis,” “conflict,” “situation,” or “events” to using the more direct “war” in their statements. This change in wording underlined their intention to avoid media tension, or at least to deflect possible accusations. Luxury brands were not afraid to use ”war” in statements as long as it was the right wording to respond to social calls.

When the war started in my country, I observed it through the fashion media framework. I spent seven years at Vogue Ukraine in the position of Fashion Features & Jewellery and Sustainability Editor. During the last five years, I advocated for sustainability in fashion, being truly convinced that it could be a platform to catalyze change by setting an example. I expected to see a reaction in the industry to such an ethically and ecologically challenging event as a war. As a Goldsmiths, University of London student, I was analyzing how the development of new forms of media influenced the principles of warfare.

Walter Benjamin described the effectiveness of the aestheticization of politics, referencing the mobilizing of masses following Nazi ideology, which happened alongside the development of moving images technology – the cinema. In particular, he described how the cinema’s power to transform everything into spectacle was used to dominate the masses. [1] Jean Baudrillard went even further, virtually questioning the reality of the Gulf War. He argued that the broadcasting of the Gulf War on TV radically changed its essential meaning (the opposition between friend and enemy, and the end goal of conquest or domination), making it possible for him to argue the simulated nature of the war in “The Gulf War Did Not Take Place.” [2] It is clear that – at least in its early days – the war in Ukraine, framed in the media as “the most online war ever,” did not take place exclusively on the battlefield. It was fought, communicated, and generally experienced under the giant influence of social media, where the affective power of war was spreading in a viral flow of contagious images and messages.

My master's dissertation was devoted to observing critically what I was already following. I studied the luxury industry's reaction to the war in Ukraine through the lens of affect theory. My findings led to the conclusion that the tension that emerged in social media plays a major role not only in spreading awareness about the war but in changing luxury and fashion brands' public responses to it. Moreover, the collective call for businesses to act morally and take the right side has shaped brands' and corporations’ responses.

In my research, I examined the narratives produced by brands as their responses to the war within the broader media landscape. Data were gathered from five corporate and 12 brand social media accounts, which were selected from a larger scoop of 10 corporate and 87 brand accounts in the luxury and mass market and examined with a textual-analysis approach. The data were gathered during Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks. This time frame was selected because the radical shift in communications in business took place within 12 days, from 24 February through 8 March.

What follows is an edited version of my favorite part of the dissertation.

The war during Fashion Week

The fashion and luxury industry remained mostly silent in communicating its position on the war in Ukraine for almost a week. On 2-3 March, the biggest luxury sector players, French conglomerates LVMH and Kering as well as independent companies such as Chanel and Prada, almost simultaneously released public statements regarding their concerns about the war in Ukraine, pledging to donate to humanitarian missions on the ground. This aligned with their temporary suspension of business operations with Russia, caused by DHL and FedEx's decision to stop shipments to that area. The loudest voice in the industry belonged to Demna Gvasalia, Balenciaga’s Georgia-born creative director. The most awaited show on the Paris schedule, on 6 March, started with the words of Ukrainian poet Oleksander Oles: “Live long, Ukraine, live for your beauty! For strength, truth, and liberty!” The poem was read by Demna himself. T-shirts in the color of the Ukrainian flag were distributed as exclusive merch to guests; despite having been arranged well before the beginning of the war, the entire show setting became purposely reminiscent of refugees walking in stormy winter weather; invitations to Russian industry players were canceled. There wasn't any doubt what the brand stood for, and this position was skillfully delivered with maximum media effect through a network of friendly, highly visible media accounts before and after the show.

Still, customers' expectations for the industry to manifest a strong moral position were not met, probably because most luxury brands limited their communications to publishing messages of support and reporting the amount of their donations on their websites, without repeating this messaging on social media, making it less visible to customers and followers who don't check corporate news sections. Interestingly, nobody was surprised that such an expectation was there in the first place.

Moral imperative

The war in Ukraine was a clear signal of change in neoliberal society, where key market players had their agency. The imperative to act ethically exists for corporations as well as customers. Businesses are expected to act responsibly towards people and wildlife and to contribute to solving social problems, much like government and non-governmental organizations (should) do. Customers strive to demonstrate commitment to ethical values in their consumer behavior; moreover, they place themselves in charge of monitoring brands' commitment to ethical values, constantly challenging them by asking #WhoMadeMyClothes or demanding that they react to ongoing social crises by supporting #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, or #StandWithUkraine.

Sociologist Avram Arvidsson named this development in society “ethical capitalism” [3] and claimed that its development is enhanced by communication technologies. According to Arvidsson, the value of business is related to ethics. He interprets the latter in the Aristotelian sense as a state of social “virtuous coexistence.” [3] He claims that the “ethical surplus” [3] determines the success of brands and describes it as a two-sided process of brand management. It is related both to the ability to develop affective attachments with customers, which motivate and inspire them to participate in brand value creation, and to the ability to attune to common contributions to society, to “support a common sense of purpose and direction that operates independently of command or monetary rewards” [3]. Importantly, ethical surplus becomes an obvious measure of public affection for the brand.

Predictably, fashion mirrored this market tendency towards “moralization” [4] and “responsibilization.” [5] For more than five years, the industry has claimed to put values at the core of its business; people and the planet are constantly in its operational focus and communications. Companies such as Pangaia, and designers such as Gabriela Hearst, owe their success almost exclusively to their passionate commitment to sustainable development. The war, which affects human life as severely as global warming, was expected to be a matter of great concern for luxury brands, too.

Call the war a “war”

In their statements regarding the war in Ukraine, luxury brands developed a discourse with moral agency, taking responsibility for solving social issues alongside government and non-governmental organizations. Relying on governments’ diplomatic efforts, they merged their own efforts with the most well-known charities and NGOs, such as the UN Refugee Agency or UNICEF, illustrating how businesses are expected to be accountable for participating in social life. Even more, it shows how brands demonstrate their ability to attune to media flow around an event created by their demanding followers. The use of the word “war” in statements is a good example.

The need to describe precisely the events in Ukraine was behind some tension on social media in the first days of the war. One of the most frequent accusations on social media was leveled at those who used an indirect description, such as “crisis” or “tragedy,” which effectively deflected blame from Russia as a country-aggressor; the call for peace and against war was perceived as a camouflaged message to the aggressor to surrender.

Prada exemplifies the tendency of luxury reactions. A screenshot of a deleted Instagram post shows that they used “crisis” in their initial statement, while the statement now on the brand's account has the word “war.” In a week, brands gradually moved from using descriptive words such as “crisis,” “conflict,” “situation,” or “events” to using the more direct “war” in their statements. This change in wording underlined their intention to avoid media tension, or at least to deflect possible accusations. Luxury brands were not afraid to use ”war” in statements as long as it was the right wording to respond to social calls.

Some narratives were created even before the industry began to act as a result of industry insiders and fashion media passionately campaigning to support Ukraine and seeking to find the right narratives to make the war a common concern. Thanks to their efforts, a network of affective attachments toward Ukraine was established. Even more, they made this war fashionable – something worth spending energy, time, and money on.

On 1 March, two days before brand statements began to be released, 1 Granary, a multi-disciplinary media platform centered around the work of young and independent talents in fashion, released an open letter titled “Fashion Unites Against War.” [6] Its key message summarized the efforts of those who demanded the industry not be silent. So far, it has been signed by 3,000 industry insiders and has been widely reposted and covered in the media. It was one of the loudest calls to the industry, shaping the moral narrative for the brands and urging them to be a platform for the community in order to consolidate efforts, and to take full accountability for being ethically responsive. All of this was widely and creatively repeated in brand statements.

The same day, Vogue Ukraine published an open letter to the industry demanding an embargo on fashion and luxury goods exported to Russia [7]; it was soon joined by Vogue editions from neighboring countries, and the letter was massively reposted by users. While the desired reaction for big corporations and brands to stop trading with Russia had yet to come, the narrative about the possible economic measures within the luxury business had already been established.

Affect, which refers to the human capacity to manifest and simultaneously produce emotions, has several interpretations, and applies well to an analysis of viral communication such as that which shaped the social media discourse around the response to war in Ukraine. The interest in affect in academic literature began in the 1990s, when the affect theory became the focus of attention of scholars from various disciplines, such as sociology, cultural and media studies, neuroscience, and psychoanalysis. Therefore, the meaning of the notion of affect depends on the field of study and might be described as sensations, atmospheres, intensities, and rhythms that lie above or below conscious awareness. I use the scholarly concept of affect, which interprets it as non-intentional and non-dependent on emotion, relying on the works of Brian Massumi (2002) and Tony D. Sampson (2012). They suggest perceiving affect as a primarily prediscursive and non-individualistic phenomenon, a purely social one, which explains how the discourse is shaped. For Sampson, the virality of certain messages, images, and symbols relies on people’s capacity to think “in the same mental images (real and imagined)” [8]. He argues that “collective contamination” spreads in the digital environment due to people’s ability to share and absorb those images and due to people’s vulnerability towards them. According to Massumi, images are experienced by receivers below the borders of consciousness, which results in affection; furthermore, affection starts to work within narratives and is shaped in discourse, where it gains meaning within the existing culture and language [9].

The affect theory might be used to illustrate how the mediatisation of the war radically influences its perception when war influences the relationship between humans and technologies. I have encountered numerous articles analyzing how affective tension in the speeches of right-wing politicians shaped a mediatic atmosphere of threat. The latter, charged with fear and suspicion, made it possible to enact more radical external policies that had previously been impossible to justify; as summarized by Massumi, “the invasion was right because in the past there was a future threat” [10]. It is equally true in the case of the preemptive invasion of Iraq by the US in 2003 (an atmosphere of fear regarding a potential breach of national security, which was already present in memories of September 11) or in Russia’s military offensive in Ukraine in 2014/2022 (as prevention from so-called Ukrainian neo-Nazis or genocide of the Russian-speaking population of eastern Ukraine, promoted by Russian propaganda).

The analysis of the most striking images of the war – wounded and killed bodies – show how affect functions depending on human-digital bounds created in the process of consuming social media. The capacity of living human bodies to feel and experience the vulnerability of wounded or killed ones results in establishing symbols of solidarity with a strong, unifying power [11] [12]. It is impossible not to be touched or moved by these images, so they function as an affective mechanism of public conscription into the war, making other opinions on the matter irrelevant. The incorporation of viewers into the war occurred even more effectively with images of children’s bodies, or toys covered in blood, like the images that appeared on 8 April after the missile attack at the Kramatorsk train station killed 57 civilians. Moreover, the images shift focus from the facts regarding the war to what this war looks like. They prove that #RussiaIsaTerroristState, and that the Russian military targets civilians and shows no mercy even to children.

Due to the traumatic and emotionally involved capacities of images, collective contamination in social media rises dramatically. The affect plays its part by creating atmospheres that cause businesses to respond. Crucially, it makes them respond in a specific way. Brands prioritize their humanitarian efforts and emphasize the help provided to those severely impacted by war, such as refugees, or women and children. Moreover, in their statements, luxury brands present themself more like a social platform than a commercial structure. They draw attention to the expertise of the organizations to which they donate and suggest that their followers join forces and contribute to institutions chosen by them. In this way, they become affiliated with the values and image of organizations such as the UN Refugee Agency or UNICEF.

The scale of this conscription might be interpreted differently. One might question, for instance, the objectivity of my research, as I was not adhering to the neutral position of the researcher; quite the opposite, as a Ukrainian, I am deeply affected by these images. Nevertheless, analysis of the media context at the beginning of the war signaled that the narratives in the fashion industry, such as the focus on helping people impacted by war, were established due to the circulation of the images of wounded and killed bodies.

The wounded body received yet another presentation during Fashion Week, which came from the side of consumer culture. It was shown within the context of “before-and-after’ images” – the term suggested by sociologist Mike Featherstone – which in its primal purpose emphasizes the results of efforts to transform the look of the body, whether those efforts are stylistic, aerobic, surgical, etc. [13]. This logic of “before-and-after’ images” is affectively charged with the idea of the constant maintenance of the body, which in neoliberal society is seen as proof of constant improvement of the quality of life.

The mechanism of presenting transformed bodies proved its selling capacity within consumer culture. During the war, bodies were shown before and after Russian missile strikes. In the earliest examples, the transformed bodies were damaged, wounded, stitched, and compared to normal ones – i.e., from before the war. Affective tools from consumer culture were used widely to represent the realities of the war using visual language with which the recipient of the fashion week content was already familiar. The affective capacities of the images similarly intensify the presence of war during Fashion Week.

On 1 March, two days before brand statements began to be released, 1 Granary, a multi-disciplinary media platform centered around the work of young and independent talents in fashion, released an open letter titled “Fashion Unites Against War.” [6] Its key message summarized the efforts of those who demanded the industry not be silent. So far, it has been signed by 3,000 industry insiders and has been widely reposted and covered in the media. It was one of the loudest calls to the industry, shaping the moral narrative for the brands and urging them to be a platform for the community in order to consolidate efforts, and to take full accountability for being ethically responsive. All of this was widely and creatively repeated in brand statements.

The same day, Vogue Ukraine published an open letter to the industry demanding an embargo on fashion and luxury goods exported to Russia [7]; it was soon joined by Vogue editions from neighboring countries, and the letter was massively reposted by users. While the desired reaction for big corporations and brands to stop trading with Russia had yet to come, the narrative about the possible economic measures within the luxury business had already been established.

Affect and war in Ukraine

Affect, which refers to the human capacity to manifest and simultaneously produce emotions, has several interpretations, and applies well to an analysis of viral communication such as that which shaped the social media discourse around the response to war in Ukraine. The interest in affect in academic literature began in the 1990s, when the affect theory became the focus of attention of scholars from various disciplines, such as sociology, cultural and media studies, neuroscience, and psychoanalysis. Therefore, the meaning of the notion of affect depends on the field of study and might be described as sensations, atmospheres, intensities, and rhythms that lie above or below conscious awareness. I use the scholarly concept of affect, which interprets it as non-intentional and non-dependent on emotion, relying on the works of Brian Massumi (2002) and Tony D. Sampson (2012). They suggest perceiving affect as a primarily prediscursive and non-individualistic phenomenon, a purely social one, which explains how the discourse is shaped. For Sampson, the virality of certain messages, images, and symbols relies on people’s capacity to think “in the same mental images (real and imagined)” [8]. He argues that “collective contamination” spreads in the digital environment due to people’s ability to share and absorb those images and due to people’s vulnerability towards them. According to Massumi, images are experienced by receivers below the borders of consciousness, which results in affection; furthermore, affection starts to work within narratives and is shaped in discourse, where it gains meaning within the existing culture and language [9].

The affect theory might be used to illustrate how the mediatisation of the war radically influences its perception when war influences the relationship between humans and technologies. I have encountered numerous articles analyzing how affective tension in the speeches of right-wing politicians shaped a mediatic atmosphere of threat. The latter, charged with fear and suspicion, made it possible to enact more radical external policies that had previously been impossible to justify; as summarized by Massumi, “the invasion was right because in the past there was a future threat” [10]. It is equally true in the case of the preemptive invasion of Iraq by the US in 2003 (an atmosphere of fear regarding a potential breach of national security, which was already present in memories of September 11) or in Russia’s military offensive in Ukraine in 2014/2022 (as prevention from so-called Ukrainian neo-Nazis or genocide of the Russian-speaking population of eastern Ukraine, promoted by Russian propaganda).

Affected and affective bodies

The analysis of the most striking images of the war – wounded and killed bodies – show how affect functions depending on human-digital bounds created in the process of consuming social media. The capacity of living human bodies to feel and experience the vulnerability of wounded or killed ones results in establishing symbols of solidarity with a strong, unifying power [11] [12]. It is impossible not to be touched or moved by these images, so they function as an affective mechanism of public conscription into the war, making other opinions on the matter irrelevant. The incorporation of viewers into the war occurred even more effectively with images of children’s bodies, or toys covered in blood, like the images that appeared on 8 April after the missile attack at the Kramatorsk train station killed 57 civilians. Moreover, the images shift focus from the facts regarding the war to what this war looks like. They prove that #RussiaIsaTerroristState, and that the Russian military targets civilians and shows no mercy even to children.

Due to the traumatic and emotionally involved capacities of images, collective contamination in social media rises dramatically. The affect plays its part by creating atmospheres that cause businesses to respond. Crucially, it makes them respond in a specific way. Brands prioritize their humanitarian efforts and emphasize the help provided to those severely impacted by war, such as refugees, or women and children. Moreover, in their statements, luxury brands present themself more like a social platform than a commercial structure. They draw attention to the expertise of the organizations to which they donate and suggest that their followers join forces and contribute to institutions chosen by them. In this way, they become affiliated with the values and image of organizations such as the UN Refugee Agency or UNICEF.

The scale of this conscription might be interpreted differently. One might question, for instance, the objectivity of my research, as I was not adhering to the neutral position of the researcher; quite the opposite, as a Ukrainian, I am deeply affected by these images. Nevertheless, analysis of the media context at the beginning of the war signaled that the narratives in the fashion industry, such as the focus on helping people impacted by war, were established due to the circulation of the images of wounded and killed bodies.

The wounded body received yet another presentation during Fashion Week, which came from the side of consumer culture. It was shown within the context of “before-and-after’ images” – the term suggested by sociologist Mike Featherstone – which in its primal purpose emphasizes the results of efforts to transform the look of the body, whether those efforts are stylistic, aerobic, surgical, etc. [13]. This logic of “before-and-after’ images” is affectively charged with the idea of the constant maintenance of the body, which in neoliberal society is seen as proof of constant improvement of the quality of life.

The mechanism of presenting transformed bodies proved its selling capacity within consumer culture. During the war, bodies were shown before and after Russian missile strikes. In the earliest examples, the transformed bodies were damaged, wounded, stitched, and compared to normal ones – i.e., from before the war. Affective tools from consumer culture were used widely to represent the realities of the war using visual language with which the recipient of the fashion week content was already familiar. The affective capacities of the images similarly intensify the presence of war during Fashion Week.

“In their statements regarding the war in Ukraine, luxury brands developed a discourse with moral agency, taking responsibility for solving social issues alongside government and non-governmental organizations.”

Importantly, another tendency emerged. [Above] is an Instagram post from The Times magazine’s account [14]. It is the story of Olena Kurylo, whose apartment block in Kharkiv was hit by a Russian missile at the beginning of the invasion. Her face and eyes were damaged by broken glass. Her image was one of the first to appear in the media and became a viral symbol of the war. This collage in The Times magazine with her “before-and-after’ images,” dated 4 June, shows the positive development of the story. She had facial surgery in Poland to save her sight, and she has continued working as a teacher.

While writing my research during the seventh month of the full-scale war, the examples of “before-and-after’ images” shifted to representing bodies as reshaped and prosthetic, healed and transformed with the help of surgery or prosthesis. The symbolic meaning of the images changed: it circled back to its affirmative connotation. In the context of war, they were perceived as a sign of the strength of Ukrainians and their capacity to overcome difficulties.

The general tendency noticed in brands' communications on Instagram was to be quiet in their PR communications while still being proactive. Big corporations such as LVMH, Kering, and OTB released statements and doubled them on their social media accounts, while the brands in their portfolios did not provide any statements, with certain exceptions such as Balenciaga or Louis Vuitton. Luxury giant Richemont did not release any statement in its accounts, but the comments of its official representatives on the organization’s philanthropic activity circulated in newspapers. Several brands published press releases on their affiliated platforms communicating social impact initiatives, such as Gucci Equilibrium and Cartier Philanthropy, clearly separating their business from their efforts to contribute to society. It points to the main pattern: the less a company deals with selling luxury goods directly to customers through its social media channels, the less neutral they are.

The war in Ukraine was not an easy topic to navigate in public communications, which brands tried to avoid as much as possible even while doing good. Moreover, while making clear whom they supported, brands did not show whom they stood against, mostly preferring not to name the aggressor. By picturing that they stand for humanity in general, brands prefer to reduce their political involvement, focusing on how much was done for Ukraine through humanitarian efforts without clarifying political preferences. Thus, the narrative shaped by the brands was depoliticized; the war was represented as a humanitarian crisis that they greatly contributed to resolving.

Nevertheless, the affective sticky and “glue-like” [15] narratives and symbols appearing in the media changed the context constantly and thus made it contagiously political. To examine how this functions, I will look at textual relationships between posts and comments. The latter functions as a destabilizing force, where intensities around certain symbols and narratives were clustered.

The letter Z, a sign worn by Russian troops participating in the invasion of Ukraine and painted on vehicles, became the symbol of the Russian invasion, an association that was quickly proven in massive numbers of images and collages that appeared on social media. The letter Z was pictured as a Nazi armband swastika. It was actively used in collages with killed bodies as a campaign targeted at brands that had not left the Russian market – for instance, #boycottnestle. By repeating these images, a new meaning was established and became dominant; now, the Z was tightly related to the narrative of Russian propaganda rather than any neutral pre-war context.

While writing my research during the seventh month of the full-scale war, the examples of “before-and-after’ images” shifted to representing bodies as reshaped and prosthetic, healed and transformed with the help of surgery or prosthesis. The symbolic meaning of the images changed: it circled back to its affirmative connotation. In the context of war, they were perceived as a sign of the strength of Ukrainians and their capacity to overcome difficulties.

Peace in yellow and blue

The general tendency noticed in brands' communications on Instagram was to be quiet in their PR communications while still being proactive. Big corporations such as LVMH, Kering, and OTB released statements and doubled them on their social media accounts, while the brands in their portfolios did not provide any statements, with certain exceptions such as Balenciaga or Louis Vuitton. Luxury giant Richemont did not release any statement in its accounts, but the comments of its official representatives on the organization’s philanthropic activity circulated in newspapers. Several brands published press releases on their affiliated platforms communicating social impact initiatives, such as Gucci Equilibrium and Cartier Philanthropy, clearly separating their business from their efforts to contribute to society. It points to the main pattern: the less a company deals with selling luxury goods directly to customers through its social media channels, the less neutral they are.

The war in Ukraine was not an easy topic to navigate in public communications, which brands tried to avoid as much as possible even while doing good. Moreover, while making clear whom they supported, brands did not show whom they stood against, mostly preferring not to name the aggressor. By picturing that they stand for humanity in general, brands prefer to reduce their political involvement, focusing on how much was done for Ukraine through humanitarian efforts without clarifying political preferences. Thus, the narrative shaped by the brands was depoliticized; the war was represented as a humanitarian crisis that they greatly contributed to resolving.

Nevertheless, the affective sticky and “glue-like” [15] narratives and symbols appearing in the media changed the context constantly and thus made it contagiously political. To examine how this functions, I will look at textual relationships between posts and comments. The latter functions as a destabilizing force, where intensities around certain symbols and narratives were clustered.

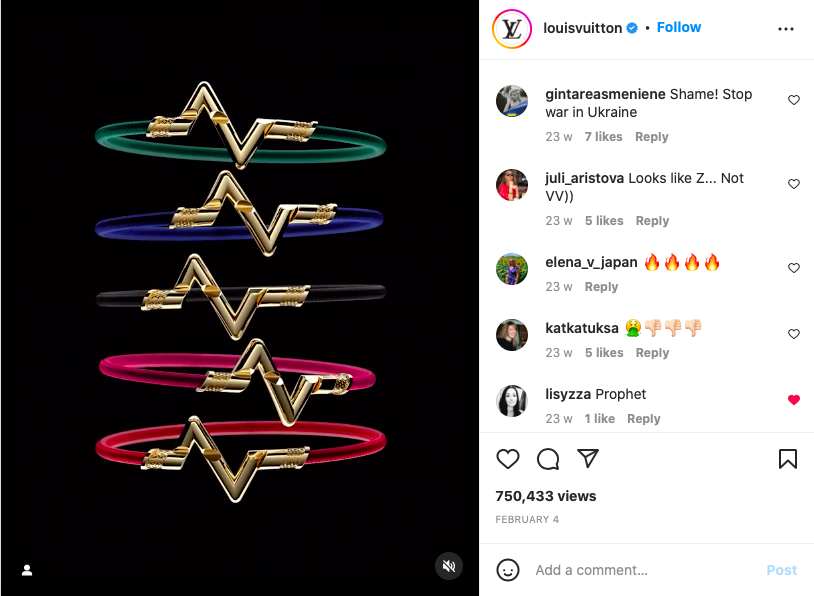

The letter Z, a sign worn by Russian troops participating in the invasion of Ukraine and painted on vehicles, became the symbol of the Russian invasion, an association that was quickly proven in massive numbers of images and collages that appeared on social media. The letter Z was pictured as a Nazi armband swastika. It was actively used in collages with killed bodies as a campaign targeted at brands that had not left the Russian market – for instance, #boycottnestle. By repeating these images, a new meaning was established and became dominant; now, the Z was tightly related to the narrative of Russian propaganda rather than any neutral pre-war context.

Louis Vuitton Instagram

Louis Vuitton InstagramThe affective intensity of the symbol Z proved itself in the case of Louis Vuitton. On 4 February the brand presented a new version of a bracelet for their unisex LV Volt collection, which was originally launched in 2020. The signature design of the collection is centered around the LV monogram rotated at 90 degrees, thus somewhat resembling a Z. The collection was developed well before the full-scale invasion, its extension was released 20 days beforehand, and it was not designed as a message to Z supporters. Nevertheless, after 24 February it was seen as Z-related. A massive number of comments appeared on LV Volt Instagram posts with emojis of Russian flags, and #RussiaIsaTerroristState with Ukrainian ones. Neither the date nor the brand description of the design were capable of stopping people from perceiving it within the new context, which quickly became contagious and spread on social media. The brand was accused of supporting the Russian invasion. As we can see from the screenshot, it was a case for a conspiracy, too. For instance, the user @lisyzza commented “Prophet,” which presumably related to the brand predicting the Z-army invasion. Surprisingly, it was not completely irrational: the mistaken accusation toward the brand was at least noticed.

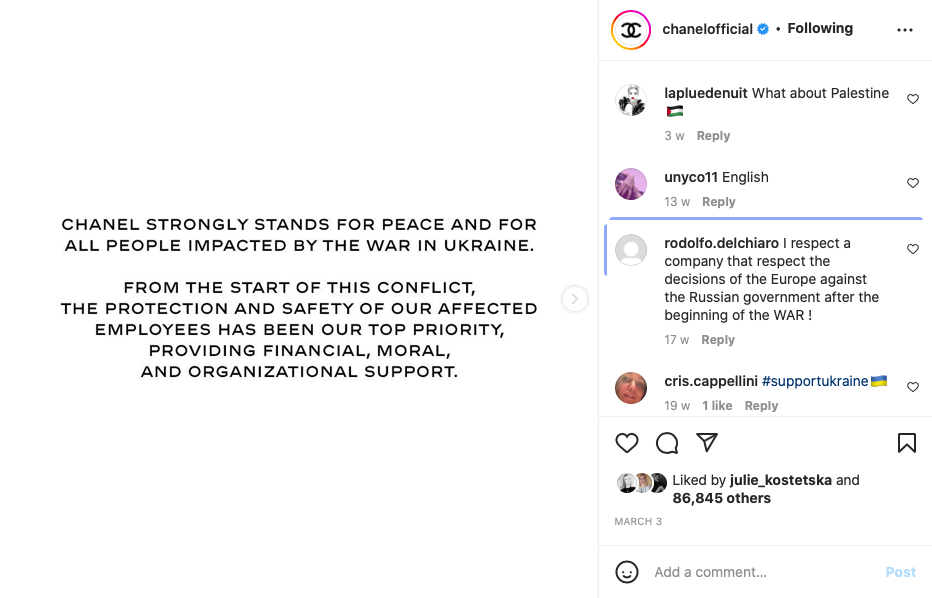

Chanel Instagram

Chanel Instagram“Brands prioritize their humanitarian efforts and emphasize the help provided to those severely impacted by war, such as refugees, or women and children.”

Political comments on Instagram influence the perception of a brand's statements and open up the possibility that brands can do it wrong or could do it better. Alongside the numerous messages of gratitude for their support, a significant number of affective comments followed general media narratives regarding the war in Ukraine. The most-repeated comments were the so-called “whataboutisms” such as “What about Palestine?” aimed at deflecting attention from Ukraine, accusing the West of aggressive actions towards other countries, and pointing out the potential threat posed by Ukrainian neo-Nazis. The nature of this narrative is not necessarily logical, and is rather shocking and disturbing, while the comments in brand accounts sometimes turn out to be a space for political battlefields between humans and bot accounts. Regardless, such contagious messages increase the level of collective contamination and influence the perception of the narrative constructed from the brand's side.

In such a contagious environment, any action is subject to intense scrutiny and liable to produce enormous affect on social media. It was intensified due to the reproduction, repetition, and circulation of viral content. Despite the brand's resistance, they were perceived and (de)valuated within the highly politicized media context.

Collective affection on social media has influenced fashion brands' communications during the war in Ukraine. Accountability and moral agency, manifested with a focus on corporate humanitarian efforts, are tightly related to the images of victims of the war, whose presence on social media changed the affective atmosphere of the Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks. The visibility of events such as Fashion Week led to increased cultural noise around the war on social media, and the political neutrality of the brands was greatly influenced by the highly politicized media landscape. All this occurred because of the changing nature of relationships between humans and technologies, which resulted in the way content is experienced bodily and transmitted in a digital environment.

In such a contagious environment, any action is subject to intense scrutiny and liable to produce enormous affect on social media. It was intensified due to the reproduction, repetition, and circulation of viral content. Despite the brand's resistance, they were perceived and (de)valuated within the highly politicized media context.

Conclusion

Collective affection on social media has influenced fashion brands' communications during the war in Ukraine. Accountability and moral agency, manifested with a focus on corporate humanitarian efforts, are tightly related to the images of victims of the war, whose presence on social media changed the affective atmosphere of the Milan and Paris Fashion Weeks. The visibility of events such as Fashion Week led to increased cultural noise around the war on social media, and the political neutrality of the brands was greatly influenced by the highly politicized media landscape. All this occurred because of the changing nature of relationships between humans and technologies, which resulted in the way content is experienced bodily and transmitted in a digital environment.

Notes: War in Fashion

[1] Berman, Russell A. “The Aestheticization of Politics: Walter Benjamin on Fascism and the Avant-garde”, Modern Culture and Critical Theory : Art, Politics, and the Legacy of the Frankfurt School. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989.

[2] Dan Oberg, (2014). “Introduction: Baudrillard and War.” International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, 11(2)

[3] Adam Arvidsson, "Ethics and Value in Customer Co-production." Marketing Theory 11, no. 3 (2011): 261-78, 289.

[4] Steve Marotta, "Windows into the Ethically Made: Affect, Value, and the 'Pricing Paradox' in the Maker Movement." Journal of Cultural Economy 15, no. 3 (2022): 344-57.

[5] Ronen Shamir, "The Age of Responsibilization: On Market-Embedded Morality." Economy and Society 37, no. 1 (2008): 1-19.

[6] 1 Granary “Fashion has power” Instagram post, 1 March 2022.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CakSA0iMMWs/?igshid=YmMyMTA2M2Y%3D (Accessed: 5 September 2022).

[7] Vogue UA. “Vogue Ukraine urges to lay embargo on fashion and luxury goods export to Russia” Instagram post. 1 March 2022. https://www.instagram.com/p/CakG2POMLS0/?utm_source=ig_embed&ig_rid=3f3a77b0-98b7-4d3d-a985-941da6eda7d6 (Accessed: 5 September 2022).

[8] Tony D. Sampson, Virality Contagion Theory in the Age of Networks. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012)

[9] Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual Movement, Affect, Sensation. Post-Contemporary Interventions. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2002)

[10] Brian Massumi, "The Future Birth of the Affective Fact." In The Affect Theory Reader, 52-70. New York: Duke University Press, 2020, 53.

[11] Leila Dawney, "Affective War: Wounded Bodies as Political Technologies." Body & Society 25, no. 3 (2019): 49-72.

[12] Katrin Döveling, Anu A. Harju, and Denise Sommer. "From Mediatized Emotion to Digital Affect Cultures: New Technologies and Global Flows of Emotion." Social Media Society 4, no. 1 (2018): 205630511774314.

[13] Mike Featherstone, "Body, Image and Affect in Consumer Culture." Body & Society 16, no. 1 (2010): 193-221.

[14] The Times. “Ukrainian who symbolised outbreak of war regains her sight” Instagram photo, 4 July 2022.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CfmJTUFOK1L/?igshid=MDJmNzVkMjY%3D (Accessed: 5 September 2022).

[15] Britta Timm Knudsen, and Carsten Stage. Affective Methodologies: Developing Cultural Research Strategies for the Study of Affect. (Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015)

Additional Resources

Sarah Banet-Weiser, Authentic TM the Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. Critical Cultural Communication. (New York: New York University Press, 2012).

Thomas J. Billard, and Rachel E. Moran. "Networked Political Brands: Consumption, Community and Political Expression in Contemporary Brand Culture." Media, Culture & Society 42, no. 4 (2020): 588-604.

Mike Hirsch, "Clough, Patricia Ticineto, and Jean Halley, Eds. The Affective Turn: Theorizing the Social." International Social Science Review 84, no. 1-2 (2009): 89.

Melissa Gregg, Gregory J. Seigworth, Sara Ahmed, Brian Massumi, Elspeth Probyn, and Lauren Berlant. The Affect Theory Reader. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010)

Akane Kanai, and Rosalind Gill. "Woke? Affect, Neoliberalism, Marginalised Identities and Consumer Culture." New Formations 102, no. 102 (2021): 10-27.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics