Photo by Yazan Aboushi. Model Samar Hussein Langhorne.

Photo by Yazan Aboushi. Model Samar Hussein Langhorne.

Joelle Firzli is multicultural fashion researcher. Her main area of interest is the intersection between fashion and cultural sustainability, exploring how the business and theory of fashion can help maintain and promote cultural identity, preservation and legacy, as well as social and climate justice. Joelle is also a fashion entrepreneur and the co-founder of Tribute Collective, a responsible multidisciplinary organization focused on elevating visibility for global ethical fashion and design, and on community building through programmings such as exhibits, workshops, and discussions about the global fashion industry.

This is a narrative about a young Arab woman named Amal and her relationship with the kaffiyeh, a cotton head and shoulder covering, woven with a black and white pattern, long synonymous with the Palestinian cause. Within this narrative, as I trace Amal’s lived experience of wearing her heirloom, I retrace in parallel the history of the kaffiyeh, first explaining its origin as a practical piece of clothing worn by Bedouins throughout the Arab world, then examining its shift from an everyday object to its inception into politics - beginning in 1930s with the first Arab Revolt, when the kaffiyeh was worn to conceal the identity of fighters, and culminating in the 1960s, when Former President of Palestine Yasser Arafat adopted it and turned it into an icon of resistance. Finally, through the eyes of Amal, I explore the adoption of the kaffiyeh in fashion when exported outside of the Arab world as a trendy accessory. The Entanglement Theory is utilized in this narrative as a tool to examine the intricacies and emotionally charged relationship between an Arab woman (Amal) and this piece of clothing. The goal is to open up a conversation about how a focus on the kaffiyeh as an object with its own agency could support its repositioning as a social unifier, a cultural symbol, and a fashion staple for the Arab people, without preconceptions or prejudices. The story is supported by a series of photographs taken by Yazan Aboushi, depicting a woman and her kaffiyeh as they navigate everyday life in a big city, where fashion becomes visible, purposeful, and embodied.

Amal loves clothes.

She nurtures a deep appreciation for their beauty, their smell, the emotions evoked by a piece of fabric. Her approach to dressing is contemplative and thoughtful, an interior and exterior practice deeply felt through her personal exploration of philosophies, feelings, and sensations. A practice deeply connected to her identity — a hyphenated one merging an Arab identity, which she inherited at birth, and the American identity she acquired as an adult. Most of all, Amal loves her kaffiyeh, the cotton head and shoulder covering woven with a black and white checkered-like pattern, worn predominantly by Arabs and associated with the Palestinian resistance movement. She feels a strong connection to its history and to the symbols it carries.

Amal was born in Palestine in the late 1980s. In her native village, the village of her ancestors, she experienced the joy of childhood, the smell of jasmine, the sounds of Umm Kulthum and Fairuz, the sight of old men drinking their kahwa (coffee) in the middle of a crowded street. Each Sunday, everyone would gather in the village square next to the stream to share a meal, dance, and laugh, while Amal and her friends played. The women in the village would join this Sunday revelry adorned in their most wonderful attire: skillfully stitched and embroidered thobes, the traditional handmade dress worn for centuries by Palestinian women. Each dress displayed distinctive motifs, colors, and styles: velvet or crepe fabrics, crochet details on the collar and sleeves, and red embroidery in the traditional Palestinian tatreez style. They wore large silver earrings and their arms were covered with bracelets and amulets.

Amal keeps a fond memory of her jeddo (grandfather). He was a charismatic man, despite his constant complaints on how things were better in the olden days. He had an imposing presence that garnered respect within the village. He used clothing to build stature, always adorned in a traditional black abaya - a long sleeved, full-length gown that trailed on the ground, with gold trimming on the front panels and around the cuffs. Common attire in her village, the kaffiyeh was omnipresent during Amal’s childhood and teenage years. Everyone around her wore it, from the fisherman on the sea to the villagers in the field, the za'ims (chiefs), and the townsmen. After folding it diagonally into a triangle, Amal’s jeddo preferred to lay his own delicately on his shoulder and occasionally over his head.

Amal’s family was not a wealthy one, but both her parents were educated. Her mother was a school teacher and her father a professor at the university in the town nearby. Besides speaking Arabic, she grew up learning English and reading Jane Austen. When she was ten years old, her father was offered an opportunity to move to the United States and teach at a leafy, reputable university in the Northeast. As the political situation in Palestine deteriorated after the outbreak of the first Intifada (1987-1991), Amal’s parents made the decision to leave their home country to secure a future for their family. They embarked on a new journey in the West, carrying with them a wealth of personal belongings, from objects to photos and clothing.

Amal loves clothes.

She nurtures a deep appreciation for their beauty, their smell, the emotions evoked by a piece of fabric. Her approach to dressing is contemplative and thoughtful, an interior and exterior practice deeply felt through her personal exploration of philosophies, feelings, and sensations. A practice deeply connected to her identity — a hyphenated one merging an Arab identity, which she inherited at birth, and the American identity she acquired as an adult. Most of all, Amal loves her kaffiyeh, the cotton head and shoulder covering woven with a black and white checkered-like pattern, worn predominantly by Arabs and associated with the Palestinian resistance movement. She feels a strong connection to its history and to the symbols it carries.

Amal was born in Palestine in the late 1980s. In her native village, the village of her ancestors, she experienced the joy of childhood, the smell of jasmine, the sounds of Umm Kulthum and Fairuz, the sight of old men drinking their kahwa (coffee) in the middle of a crowded street. Each Sunday, everyone would gather in the village square next to the stream to share a meal, dance, and laugh, while Amal and her friends played. The women in the village would join this Sunday revelry adorned in their most wonderful attire: skillfully stitched and embroidered thobes, the traditional handmade dress worn for centuries by Palestinian women. Each dress displayed distinctive motifs, colors, and styles: velvet or crepe fabrics, crochet details on the collar and sleeves, and red embroidery in the traditional Palestinian tatreez style. They wore large silver earrings and their arms were covered with bracelets and amulets.

Amal keeps a fond memory of her jeddo (grandfather). He was a charismatic man, despite his constant complaints on how things were better in the olden days. He had an imposing presence that garnered respect within the village. He used clothing to build stature, always adorned in a traditional black abaya - a long sleeved, full-length gown that trailed on the ground, with gold trimming on the front panels and around the cuffs. Common attire in her village, the kaffiyeh was omnipresent during Amal’s childhood and teenage years. Everyone around her wore it, from the fisherman on the sea to the villagers in the field, the za'ims (chiefs), and the townsmen. After folding it diagonally into a triangle, Amal’s jeddo preferred to lay his own delicately on his shoulder and occasionally over his head.

Amal’s family was not a wealthy one, but both her parents were educated. Her mother was a school teacher and her father a professor at the university in the town nearby. Besides speaking Arabic, she grew up learning English and reading Jane Austen. When she was ten years old, her father was offered an opportunity to move to the United States and teach at a leafy, reputable university in the Northeast. As the political situation in Palestine deteriorated after the outbreak of the first Intifada (1987-1991), Amal’s parents made the decision to leave their home country to secure a future for their family. They embarked on a new journey in the West, carrying with them a wealth of personal belongings, from objects to photos and clothing.

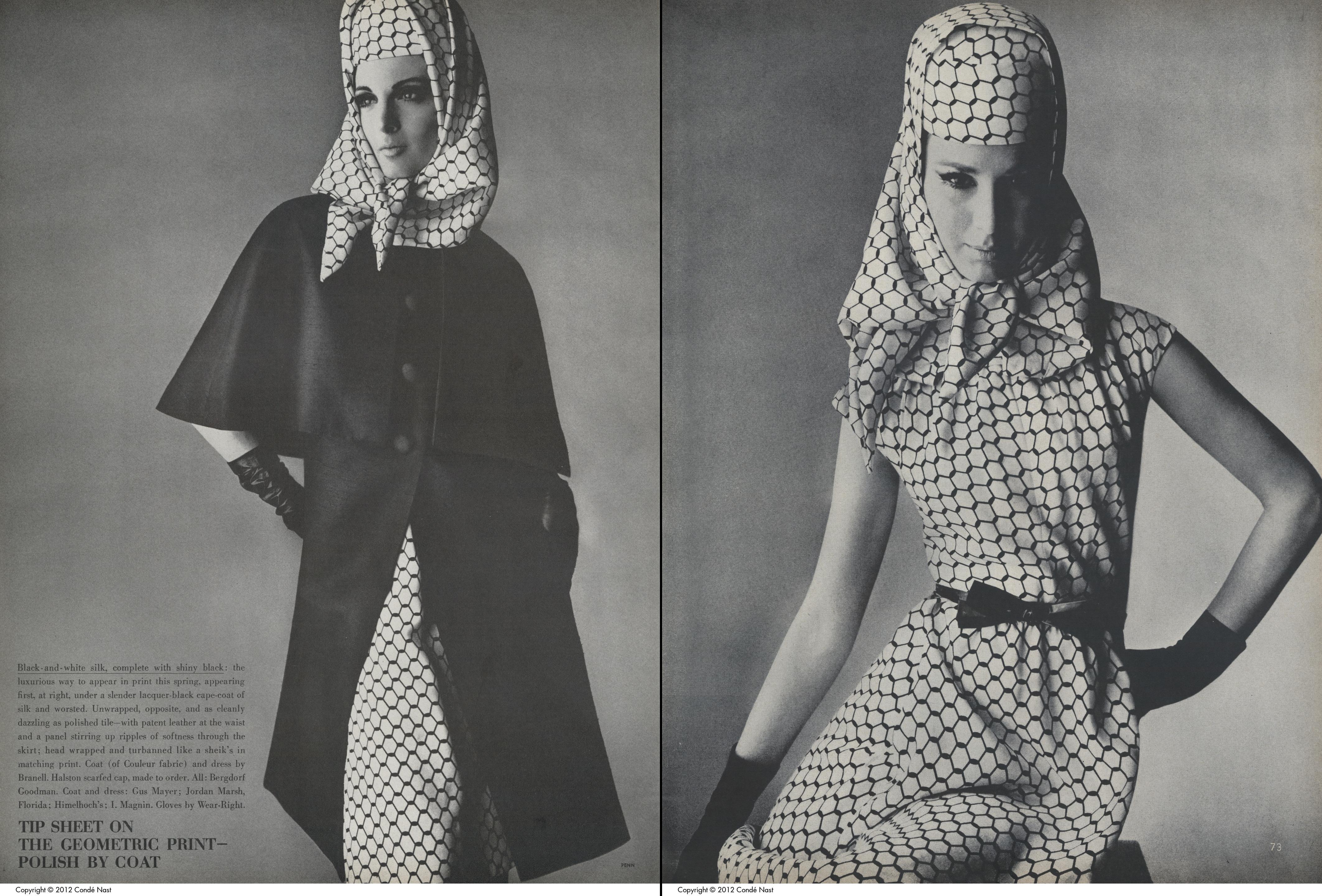

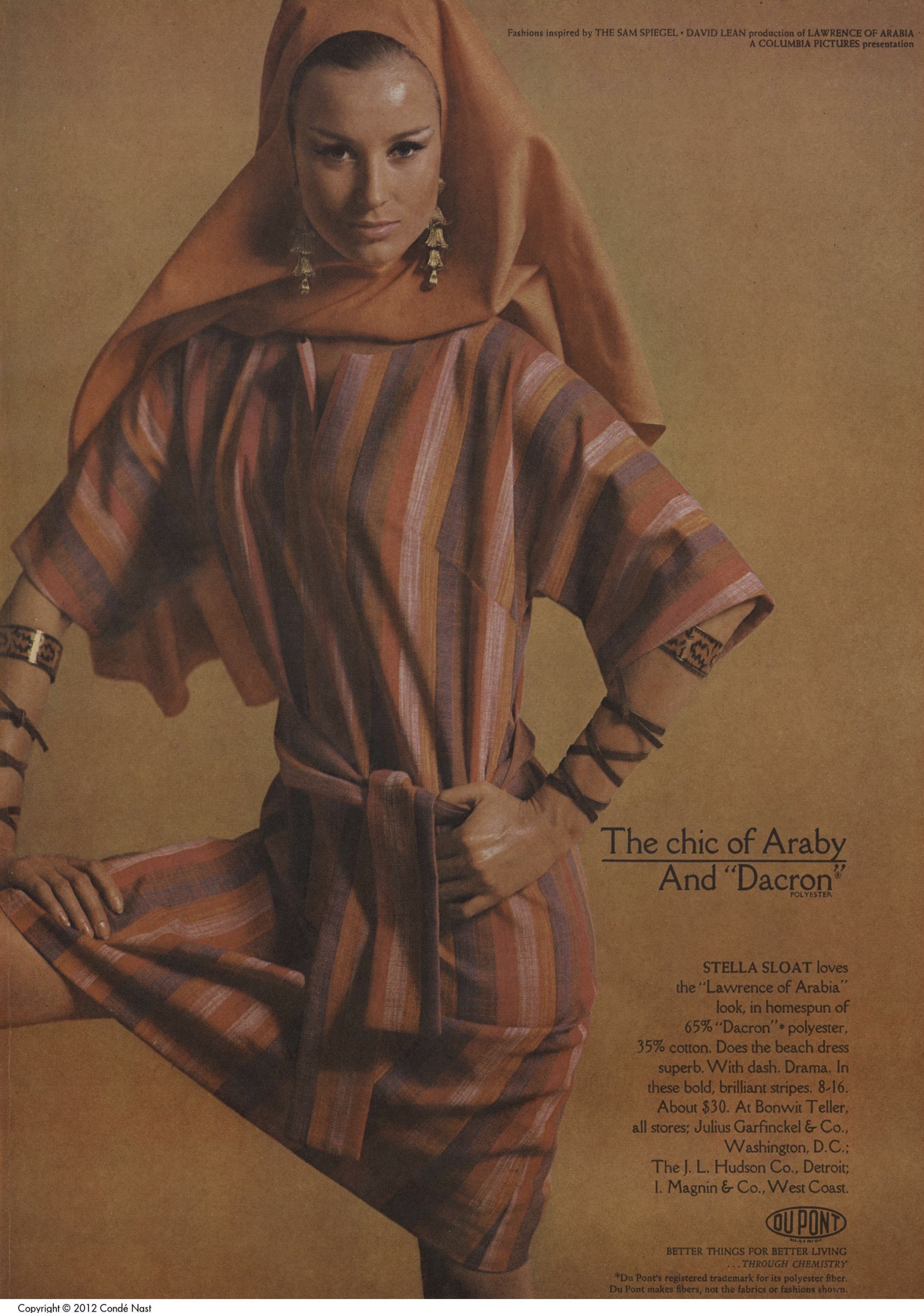

Editorial from US Vogue, February 1965. Courtesy of Condé Nast.

Editorial from US Vogue, February 1965. Courtesy of Condé Nast.“My identity is what prevents me from being identical to anybody else.” - Amin Maalouf, In the Name of Identity [1]

Seeking to preserve the memory of their origins, their new home was covered in relics and other remembrances of their life left behind. The most nostalgic of them was perhaps Amal’s mother. With her long black curly hair and almond eyes that she always blackened with kohl, she opted to cultivate her Arab identity through her sartorial choices. She was different. That difference, as she liked to say, was her super power. She was a sight in this new land, moving through the gray street-scape of a foreign town dressed in a colorful embroidered dress, adorned in all her silver jewelry, and with a black and white kaffiyeh around her neck. She carried herself with confidence.

She was proud of her identity, always reminding her daughter of how lucky she was to have two homes, two languages, two cultures — sentiments Amal learned to cultivate and protect over the years. It was a state of mind that shaped her entire life, and clothing provided her with a vehicle to express this cross-cultural identity.

When Amal was still a young girl, she and her family would fly back to Palestine to visit relatives. During that period, Amal would spend most of her time at her maternal grandparents’ house, a stone building with a red roof and green window shutters, tucked in the mountains and surrounded by olive trees. In the many years since she had lived there, nothing much had changed, the warm grape-scented air pouring in the house on a breezy afternoon, the smell of dried thyme in the morning, and the melody of the adhan, the muezzin’s call for prayer. Her jeddo in the backyard, donning his kaffiyeh while dutifully caring for his crops. She liked tending to the garden with him.

She would tell him about her achievements in school and describe her latest favorite movie. He would tell her about the origins of their family, his love for his little plot of land, and the rumiyahs, the hundreds-of-years-old twisted olive trees presiding over his property. He taught her about the poetry of identity and the complexities of otherness. “We can be many things together,” he used to say, “as long as you can respect them, control them, and live with them.” Every now and then, he would pause his stories to readjust his kaffiyeh and, as much as she liked to hear about family prowess and the best way to extract fresh olive oil, she was mostly curious to learn about the checkered piece of fabric that never left his shoulders.

One day, as they were sitting in the living room playing tawleh (backgammon), she asked: “What makes it so special?” And as he unwrapped his kaffiyeh to fix it, he shared “it is our symbol of pride.”

“It holds the key that unlocks the gate to time-travel, back to the cradle of civilization, in ancient Mesopotamia” he continued. Amal tucked herself in the corner of the couch, abandoning any attempts at playing.

Photo by Yazan Aboushi. Model Samar Hussein Langhorne.

Photo by Yazan Aboushi. Model Samar Hussein Langhorne.“The kaffiyeh spread through the region due to its practical and utilitarian design, becoming an essential piece of clothing for Bedouins.”

In Arabic, kaffiyeh (also referred to as shemagh, ghutra, or hattah) means “from the Iraqi city of al-Kufa”, about 100 miles south of Baghdad. Its original design can be traced back to Sumerian times (4100-1750 BCE), when high priests from Uruk wore their hair bound by a filet and created the fishnet-like pattern. [2] Even though it prospered during the rise of Islam (632 and c.700 CE), there is little religious significance placed on it as Christians, Muslims, Druze, and secular Arab men all wore it. The kaffiyeh spread through the region due to its practical and utilitarian design, becoming an essential piece of clothing for Bedouins who used to wrap it over their heads and cover their faces with its hems as a shield against the harsh sun and severe sandstorms of the desert. It was the common attire of the fellah (peasant), while the effendi, the educated middle-class men from the cities, wore the maroon tarbush, the traditional flat-topped hat. [3] The kaffiyeh can vary in color depending on the region. The red and white kaffiyeh is traditionally associated with Jordan; during the 1930s, British Officer John Bagot Glubb requested it be part of the uniform of the Desert Patrol — a Bedouin unit of the Arab Legion that he created in Transjordan.[4] The black-and-white kaffiyeh is most common in Palestine, where it is widely used as a protective head covering. In the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, the kaffiyeh is completely white and slightly thinner. During the 1936-1939 Arab Revolt, while Palestine was under British Mandate, the black and white kaffiyeh appeared as the ideal conduit of resistance. Creating a new united front of villagers and townspeople alike, Palestinians adopted the headscarf to cover their faces and conceal their identity, making it difficult for the British to distinguish rebels from civilians. [5] This moment marked an important turning point for the kaffiyeh, shifting from a simple utilitarian piece of clothing meant to protect men from harsh weather, to a garment representing the unity of people fighting to defend their land against the British occupier. It began to resemble its checkered design, the intersecting lines now representing a clash of social and political affairs.

After a predictable victory at tawleh, Amal’s jeddo stood up, walked towards one of the side tables, and picked up two framed photos. He explained that in the 1960s Yasser Arafat, then Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, endorsed the black-and-white kaffiyeh as a statement piece and symbol of a whole nation. Placed over his head, it took the form of an internationally recognized and powerful symbol, entrenched in Palestinian and Arab consciousness as well as politics. Handing Amal one of the pictures, he added, “Arafat never ceased to wear it, and was never seen or photographed without it.” He was famous for wrapping it in a very distinct manner, positioning it flat on the top of his head and fastening it with an agal, with the longer end of the fabric placed over his right shoulder arranged to represent the map of Palestine prior to the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. [6]

The other photograph was of Leila Khaled, a 1970s activist and member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Amal noticed how the woman proudly adorned her kaffiyeh in a headscarf style, crossing the gender line. This marked its rise in popularity among women as a symbol of unity.

“It carries the collective memory of generations of Arab men and women who wrapped their heads, way before me,” Amal’s jeddo resumed before pouring himself a cup of dark coffee that smelled of cardamom, “to wrap yourself in the kaffiyeh means to wrap yourself in tradition and geographies, in suffering but also in accomplishment.” he concluded, placing his hands on his legs to get up, ready for his nap.

Amal recalls this last statement vividly. An everyday object inseparable from Arab identity, wearing it meant to be connected to her history, and to continue to participate in its heritage. She wanted to perpetuate that tradition too. She knew one day she would own one.

After a predictable victory at tawleh, Amal’s jeddo stood up, walked towards one of the side tables, and picked up two framed photos. He explained that in the 1960s Yasser Arafat, then Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization, endorsed the black-and-white kaffiyeh as a statement piece and symbol of a whole nation. Placed over his head, it took the form of an internationally recognized and powerful symbol, entrenched in Palestinian and Arab consciousness as well as politics. Handing Amal one of the pictures, he added, “Arafat never ceased to wear it, and was never seen or photographed without it.” He was famous for wrapping it in a very distinct manner, positioning it flat on the top of his head and fastening it with an agal, with the longer end of the fabric placed over his right shoulder arranged to represent the map of Palestine prior to the creation of the state of Israel in 1948. [6]

The other photograph was of Leila Khaled, a 1970s activist and member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Amal noticed how the woman proudly adorned her kaffiyeh in a headscarf style, crossing the gender line. This marked its rise in popularity among women as a symbol of unity.

“It carries the collective memory of generations of Arab men and women who wrapped their heads, way before me,” Amal’s jeddo resumed before pouring himself a cup of dark coffee that smelled of cardamom, “to wrap yourself in the kaffiyeh means to wrap yourself in tradition and geographies, in suffering but also in accomplishment.” he concluded, placing his hands on his legs to get up, ready for his nap.

Amal recalls this last statement vividly. An everyday object inseparable from Arab identity, wearing it meant to be connected to her history, and to continue to participate in its heritage. She wanted to perpetuate that tradition too. She knew one day she would own one.

“On foreign bodies, the kaffiyeh is divorced from its Arab identity: it becomes an “exotic” object, labeled as a mere oriental fashion item and, most importantly, depleted of any cultural association.”

Dress acting as a catalyst in the struggle for social change, as a means of legitimating and contesting authority as well as producing values, is not a new concept. [7] Besides the kaffiyeh, we can identify at least two other great examples in history where dress has been central to resistance and domination. First, in 1918 with Mahatma Gandhi, who popularized the dress of Indian villagers by wearing a khadi (hand-spun and woven natural fibre cloth); then with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who in 1925, in an attempt to modernize the country, ordered Turkish men to wear Western-style hats instead of the traditional fez. [8] In both cases, as with the kaffiyeh, dress acted as a conduit for the creation of an identity, heightening messages of solidarity or resistance, inspiring feelings of nationhood and the belief that “we are all in this together.”

The following summer, her jeddo passed away. Amal, who had just turned 18, accompanied her mother to his funeral. They stayed in the same stone house surrounded by memorabilia, books, old photographs, and all the belongings of her dear grandfather. The sweet smell of cardamom still embraced the silenced and mourning house.

And there it was, on the table, crumpled but proud: his kaffiyeh. Along with the scarf was a handwritten note from her jeddo. It read: Ila Amal, ma’ kul houbi (To Amal, With all my Love).

She wrapped it around her shoulders to comfort her sadness. She felt his embrace, his warmth. He would remain close to her, she felt.

Upon their return to the United States, Amal was getting ready to start university. She had chosen to focus her studies on Middle Eastern history. She was determined to pursue a career as a historian, inspired by her grandfather’s stories and by a strong sense of duty towards her ancestors. In an attempt to mediate both her identities, she adopted a style of clothing at the crossroad between Eastern and Western wear. She enjoyed combining traditional dress such as kaftans with a touch of modernity, mixing and matching the garments she inherited from her mother with contemporary pieces found at the neighborhood store. As a young rebellious political science student trying to understand the geopolitics of her torn region, she was rarely seen around campus without her kaffiyeh. She wore it proudly wrapped around her neck, fully aware it was a visible marker of Arab cultural identity and conscious of its political association with the people of Palestine.

What Amal did not foresee was the series of political events that led to a dramatic shift in the narrative of the checkered garment. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the Shi’a resistance movement against Saddam Hussein in Iraq, in which militants were seen wearing the kaffiyeh, brought Arabs to public attention while also putting them at risk and in danger of discrimination. Politicized more than ever, the kaffiyeh was now associated with radical groups in Afghanistan as well as around the Arab world; wearing it was arguably seen in the West as a sign of support for extremism.

The following summer, her jeddo passed away. Amal, who had just turned 18, accompanied her mother to his funeral. They stayed in the same stone house surrounded by memorabilia, books, old photographs, and all the belongings of her dear grandfather. The sweet smell of cardamom still embraced the silenced and mourning house.

And there it was, on the table, crumpled but proud: his kaffiyeh. Along with the scarf was a handwritten note from her jeddo. It read: Ila Amal, ma’ kul houbi (To Amal, With all my Love).

She wrapped it around her shoulders to comfort her sadness. She felt his embrace, his warmth. He would remain close to her, she felt.

Upon their return to the United States, Amal was getting ready to start university. She had chosen to focus her studies on Middle Eastern history. She was determined to pursue a career as a historian, inspired by her grandfather’s stories and by a strong sense of duty towards her ancestors. In an attempt to mediate both her identities, she adopted a style of clothing at the crossroad between Eastern and Western wear. She enjoyed combining traditional dress such as kaftans with a touch of modernity, mixing and matching the garments she inherited from her mother with contemporary pieces found at the neighborhood store. As a young rebellious political science student trying to understand the geopolitics of her torn region, she was rarely seen around campus without her kaffiyeh. She wore it proudly wrapped around her neck, fully aware it was a visible marker of Arab cultural identity and conscious of its political association with the people of Palestine.

What Amal did not foresee was the series of political events that led to a dramatic shift in the narrative of the checkered garment. The terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the Shi’a resistance movement against Saddam Hussein in Iraq, in which militants were seen wearing the kaffiyeh, brought Arabs to public attention while also putting them at risk and in danger of discrimination. Politicized more than ever, the kaffiyeh was now associated with radical groups in Afghanistan as well as around the Arab world; wearing it was arguably seen in the West as a sign of support for extremism.

“The web of racism, cultural stereotypes, political imperialism, dehumanizing ideology holding in the Arab or the Muslim is very strong indeed, and it is this web which every Palestinian has come to feel as his uniquely punishing destiny.”

- Edward Said, Orientalism [9]

Concurrently, the headwear started drawing the attention of the fashion world. Amal began to spot it in the pages of fashion magazines. Designers such as Nicolas Ghesquière for Balenciaga (in 2007) and Riccardo Tisci for Givenchy (in 2010) incorporated the design and print in their collections. Amal saw it knotted around the necks of the fashion-savvy and on celebrities such as Mary-Kate Olsen and David Beckham. In these cases, it was in different color combinations, only rarely referencing the Palestinian black and white. [10] Entering the mainstream as a fashion accessory, the kaffiyeh trend gradually trickled down, leading to its mass production for retailers such as Urban Outfitters who marketed it, as an “anti-war woven scarf.” Considered a provocative fashion trend, protests prompted their cancellation from fashion collections, but the item could still be found online. [11] In May 2021, Louis Vuitton attempted to revive the trend by introducing a “Monogram Keffieh.” Once again, following backlash, the luxury French brand was forced to remove the product from production. [12]

Amal welcomed cultural exchange as a means of knowledge sharing; however, she was perplexed by the fact that many of the kaffiyeh adopters, although enamored with the object, seemed to know little about its history, depriving it of its original symbolic value and wearing it strictly for its aesthetic appeal.

In truth, the Western fascination with the kaffiyeh goes way back. An important moment in its polarization is the iconic photo of Thomas E. Lawrence, known as Lawrence of Arabia, portrayed wearing the headscarf while fighting alongside Arabs against the Ottomans during World War I and the Arab revolt of 1916-1918. [13] This image was later reproduced in the movie Lawrence of Arabia (1962), with Peter O’Toole depicted wearing a white kaffiyeh fastened by an agal made of thick golden wool coils. In the movie, O’Toole can be seen wrapping the end of the headscarf around his face and neck as a shield from the blazing desert sun, the same way Arab men did.

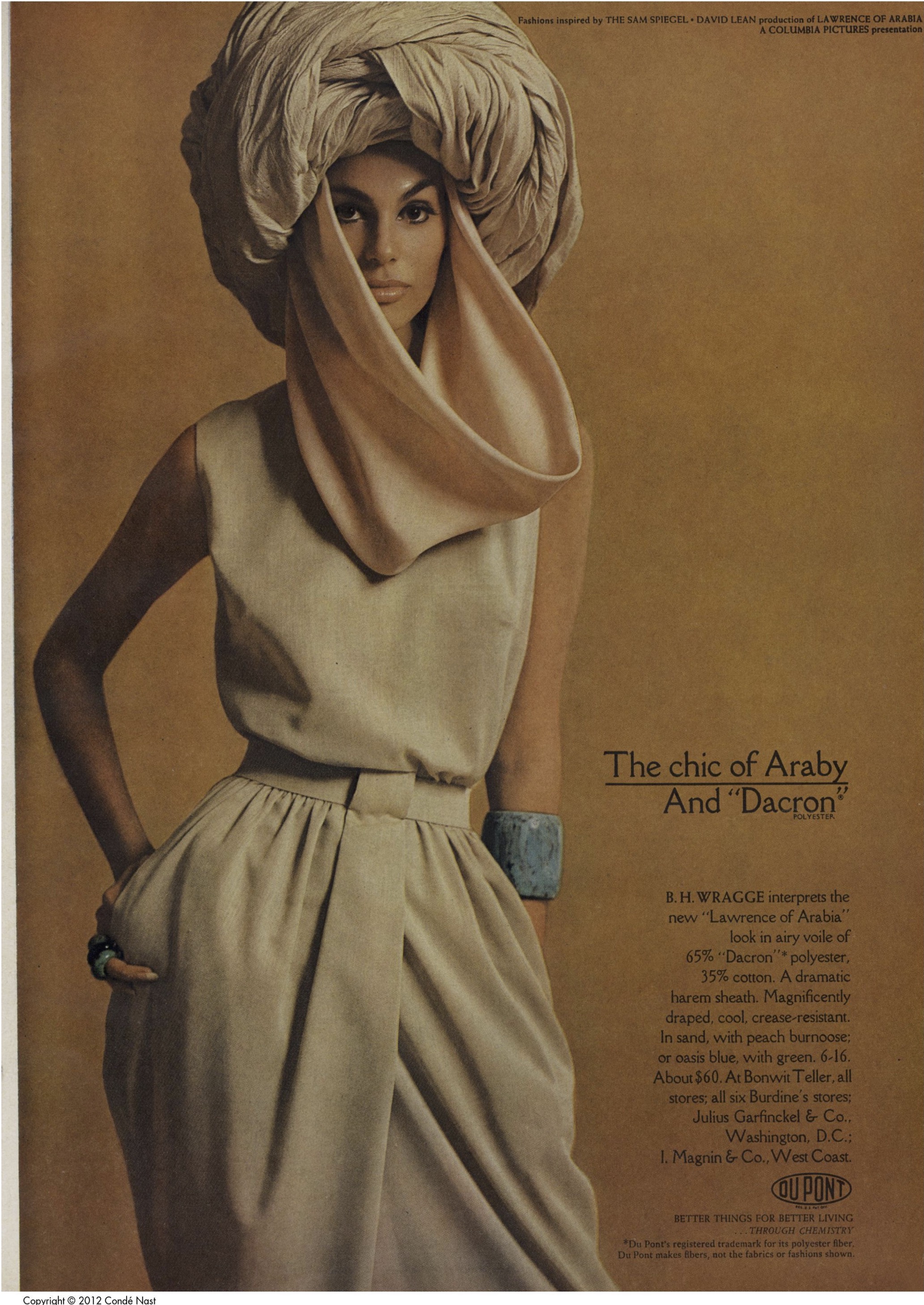

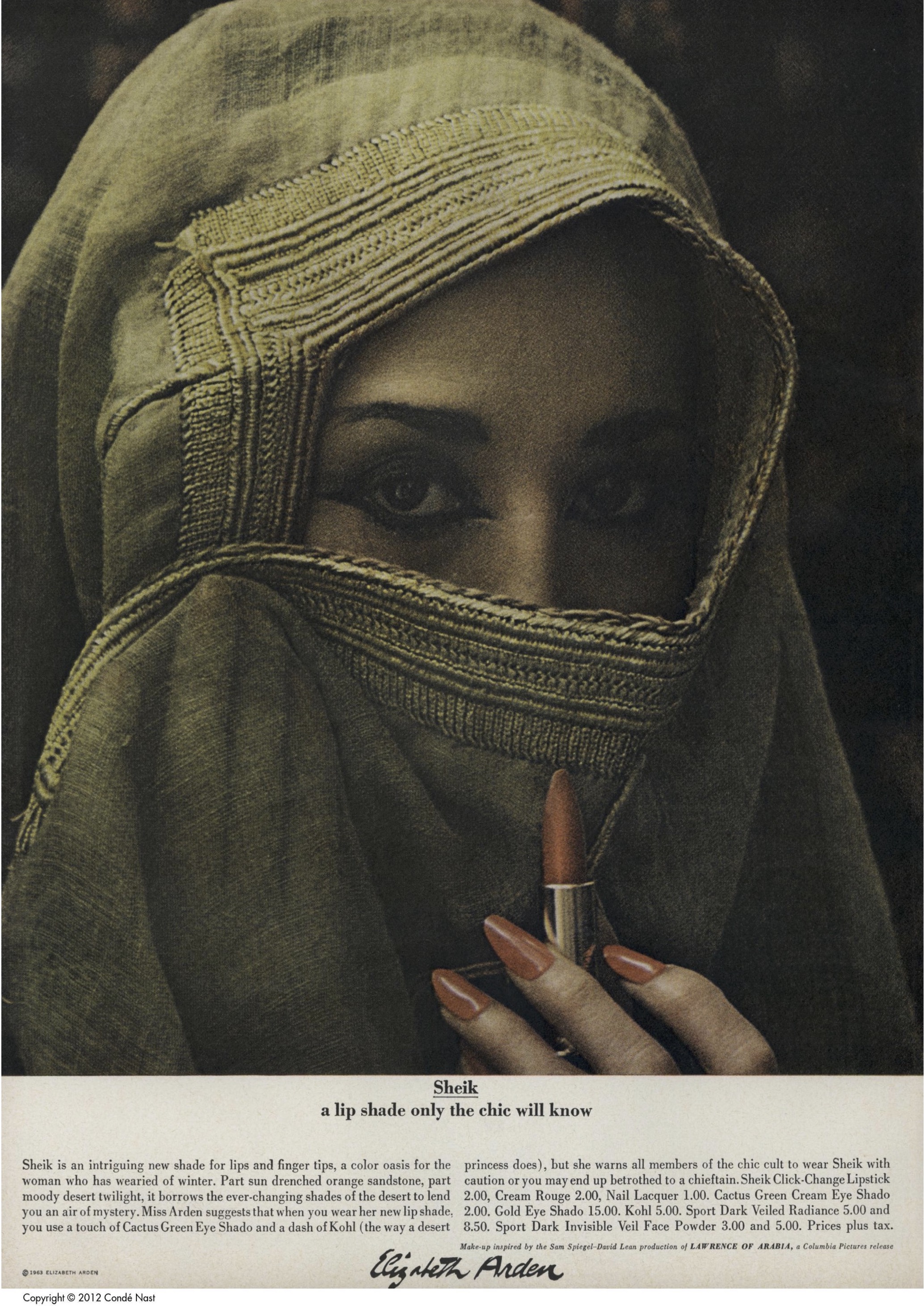

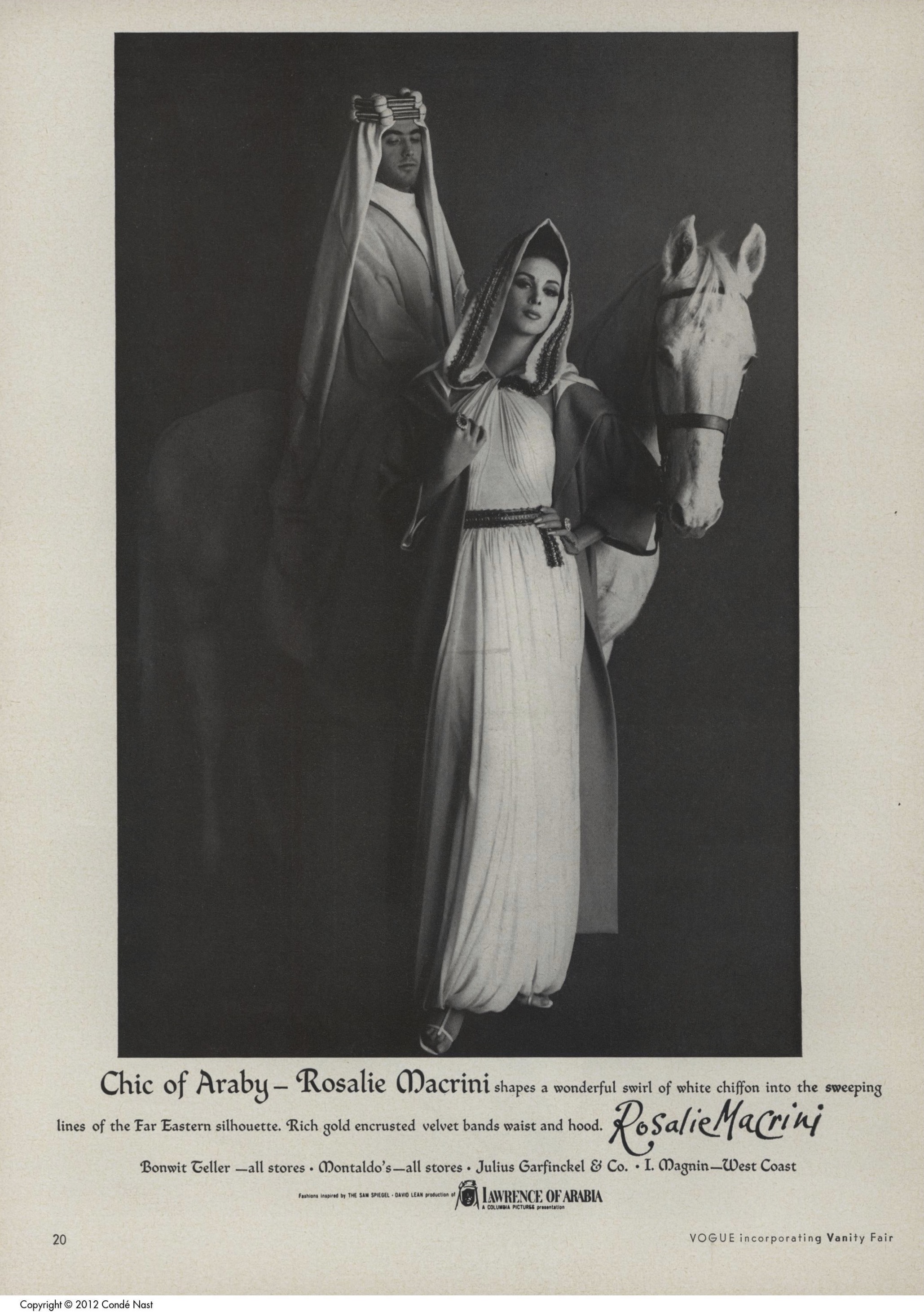

The kaffiyeh’s proliferation in the West was always supported by the fashion media. Following the success of Lawrence of Arabia, in January 1963, Vogue US introduced a new trend called “Desert Dazzle”, Elizabeth Arden released a series of “Sheik” beauty products, while American designers like Bernard H. Wragge and Stella Sloat designed collections inspired by the “Lawrence of Arabia Look.” [14] For the 1965 February issue of Vogue, a model “head wrapped and turbaned like a sheik” was photographed wearing a black and white outfit by Gus Mayer, the pattern clearly evoking that of the kaffiyeh. [15]

On foreign bodies, the kaffiyeh is divorced from its Arab identity: it becomes an “exotic” object, labeled as a mere oriental fashion item and, most importantly, depleted of any cultural association. Its commercialization and mediatization continues to produce new meanings in changing historical contexts, deeply affecting those who have been wearing it for generations.

In May 2008, Amal came across a news article: “Dunkin' Donuts Pulls Rachael Ray Ad After Complaints.” The celebrity chef was wearing a fashionably knotted kaffiyeh. Slamming the scarves as "Hate Couture," American conservative political commentator Michelle Malkin accused Ray of supporting extremists. She wrote: "the keffiyeh, for the clueless, is the traditional scarf of Arab men that has come to symbolize murderous Palestinian jihad […] a regular adornment of Muslim terrorists appearing in beheading and hostage-taking videos, the apparel has been mainstreamed by both ignorant (and not so ignorant) fashion designers, celebrities and left-wing icons.” [16]

To Amal, the use of such language to describe the kaffiyeh and the people wearing it seemed dehumanizing, disconnected from any history, limiting, and misleading. The headscarf was positioned in a category that separated it from its original historical, utilitarian, and cultural meaning, assuming now the form of an object of controversy and hatred. Its proliferation had encouraged its depreciation and diminished its significance with every wave of appropriation. The way the kaffiyeh was mediated stood in contrast to its history and to its complex symbolism. The depiction and public image of Arabs wearing the kaffiyeh in the Western media has overshadowed the enduring memory of farmers who have worn this iconic headwear for generations, a heritage, that seemed now, to be othered and forgotten.

Editorial from US Vogue, January 1963. Courtesy of Condé Nast.

Editorial from US Vogue, January 1963. Courtesy of Condé Nast.“My friend, I am not what I seem. Seeming is but a garment I wear - a care-woven garment that protects me from thy questionings and thee from my negligence.”

- Khalil Gibran, The Madman: His Parables and Poems [17]

Amal’s identity turned against her in a hostile manner when one of her classmates asked her to take off her kaffiyeh, arguing that the object was “offensive and too political.” “You can’t wear it here,” they told her, “it is causing distress to other students.” This comment incited a dormant sense of estrangement and grief, creating sentiments of mischaracterization. If clothes act as a social identifier, they represent our identities and they “are influenced by, and contribute to, the cultures and time in which we live '' [18]. Amal had initially wanted to distinguish herself by wearing the kaffiyeh, but she did not want that anymore. The way she was perceived had nothing to do with her initial intention; her own reality was ringed by prejudices and she struggled with the stereotypes, combatting the kaffiyeh’s association with hatred that led to being slandered or mischaracterized as offensive. As someone who lived in the US with the proud heritage of an Arab mother and grandfather, she felt torn between exclusion and inclusion, between love and hate. For her, the kaffiyeh had always been a silent communicator, sending intentional messages to others who spoke the same language. [19] Now it was lost in a cacophony of meanings and associations. A simple style choice suddenly symbolized discontent and ignited a long-simmering debate about the politics of clothing.

Quoting Ian Hodder, Amal was “entangled” in her kaffieyh. Hodder writes that humans use “material culture to symbolize, to exchange and to manipulate social relations.” [20], Amal relied on her kaffiyeh to construct and preserve her identity, standing in solidarity with a cause close to her heart and her family. Her kaffiyeh, in turn, was entangled in Amal’s story. The relationship of dependency often goes both ways, as things made by people grant them specific abilities when it comes to usage, care, and discard. “Things depend on humans all along the behavioral chains and throughout their used life;” [21] thus, they can also limit how humans operate.

Amal had inserted a certain degree of emotion into her kaffiyeh, de-objectifying it through personification and lived experiences. Witnessing the commodification of her family heirloom and its misinterpretation left her feeling as if she had failed to protect it. With cultural fracture, her kaffiyeh’s reality shifted. An intimate, subjective, innate relationship turned into a public, objectified, and vilified relationship. With a heavy heart, she made the decision to silence it, removing it from her wardrobe. Reluctantly, she packed her kaffiyeh away, not knowing if they would ever meet again.

The kaffiyeh, a man-made object, has undergone many changes in usage and meaning. Intentionally created as a functional object, it evolved, grew, and transformed according to the different meanings it was given. The tensions and easy slippage in its representation lie in its transposable meanings, from Arab identity to solidarity with Palestinian liberation, disdain for Arabs, political affiliations, extremism, and global trends. The kaffiyeh cannot escape politics.

Editorial from US Vogue, January 1963. Courtesy of Condé Nast.

Editorial from US Vogue, January 1963. Courtesy of Condé Nast.“Silence is the creation of space, a space that memory needs to use . . . an incubator [...] Silence demands the nature of night, even in full day, it demands shadows.”

- Etel Adnan, Shifting the Silence [22]

Fourteen years have passed since Amal buried her kaffiyeh. Since then, she has secured a position as a research fellow in a reputable institution, she is the proud owner of a one-bedroom apartment in the city, and the legal guardian of a mischievous brown cat.

On Saturday morning, she took the train north to spend the weekend at her parents’ house. As always, her mother cooked one of her favorite dishes as they caught up at the dining table, exchanging anecdotes and stories of the last few months. As always, they played a round of tawlet, and dug into old photo albums.

In the afternoon, while everyone was enjoying a nice nap outside, Amal was sifting through the chaos of old boxes stacked in the closet of her old bedroom, when one specific box labeled Stuff/Family piqued her curiosity. She could not really remember what was left in that box, so she grabbed it, placed it on her old desk, and tore the tape. And there it was, crumpled at the bottom: her forgiving kaffiyeh, in a nearly pristine state, carrying all the wright of her past. She freed it from its confinement, shook the dust off and draped it on her shoulders, bringing back a wealth of memories. Overtaken by emotions, she sat down on the chair next to her old desk and. while holding it, she felt a mix of mourning and nostalgia, renewed memories of her jeddo but also separation with his beloved garment.

Amal realized that the problem did not concern the kaffiyeh, or its wearer. The problem came from external factors such as preconceptions and mediated ideas. Critics were not focusing on the object itself but on the system of meanings imposed on it. When culturally and politically charged objects like the kaffiyeh penetrate mainstream society, their meaning moves quickly and can be transformed and sometimes completely altered or mutated like in a game of broken telephone (which in French is called téléphone arabe, Arab phone).

Amal checked her phone: 6:15 p.m. It was time to go. She placed the box back in the closet where it belonged. The kaffiyeh would come with her. She wrapped it around her neck, kissed her parents goodbye, and returned to the train station. Sitting on the train back to the city, and until she arrived home, she kept it around her neck. Their reunion was sufficient to remind her of their shared common past. She realized that the fondness she had for that scarf was not a pretense. It was actually a deep and honest appreciation, a respect, and that suddenly the past’s bitterness was distilled into gratitude.

“Symbols matter, especially for oppressed people.” - Khaled Beydoun [23]

When we regard clothes as somehow frozen in time and stagnant, we lose sight of them as fashioned and embodied. Clothes are not meant to be dormant but are supposed to transform over time. The kaffiyeh is precisely such an object — a potent design that merges and fuses meanings and symbols, opening a wide discourse on identity, politics, and culture. Its utility, convenience, and adaptability, combined with its simplicity, make it an extraordinary item. An antithesis to fashion, perhaps, it remains a cultural artifact with great political and aesthetic power.

The kaffiyeh is an entangled object. Whether wrapped around the neck or laid on the shoulders, it is first and foremost a quintessentially Arab garment, with Arab origins and an Arab history that cannot be erased, interwoven culturally and linguistically with Arab Identity and Palestinian solidarity. For Amal, the kaffiyeh is her culture. It is a door to her family’s past and to her grandfather's country. Her country. As an object with its own agency, it can be set free from its negative connotations, it can be repositioned as a social unifier, a tool for shaping ideals of social justice, a symbol of Palestinian nationalism, and a cultural and fashion staple of the Arab people without preconceptions or prejudices. It becomes a resource for change.

The next morning, Amal wraps her kaffiyeh around her neck in a nonchalant way, ready to walk the concrete stage of the city again. She wears it not only as a tribute to her heritage but as a reminder that she exists and that her culture and history are real. After all, Amal in Arabic means “hope.”

Notes: Untangled

[1] Amin Maalouf, In the name of Identity: Violence and the Need to Belong (New York, Penguins Book, 2000), 10.

[2] Milbry, Polk and Angela M.H. Schuster, The Looting of the Iraq Museum, Baghdad: The Lost Legacy of Ancient Mesopotamia, (New York: Abrams Books, 2005), 87.

[3] “Traditional Urban Men’s Dress of Saudi Arabia,” Saudi Arabesque, August 29, 2016, http://saudiarabesque.com/traditional-urban-men-s-dress-of-saudi-arabia/.

[4] Ezra Karmel, “The ‘Jordanian’ Keffiyah, Redressed,” 7iber, January 4, 2015, https://www.7iber.com/2015/01/the -jordanian-keffiyah-redressed/.

[5] Faegheh Shirazi‐Mahajan, “The politics of clothing in the middle east: The case of Hijab in post‐revolution Iran,” Critique, Journal of the Critical Studies in the Middle East 2:2 (1993): 57-58.

[6] Rashid Khalidi, The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine: A History of Settler Colonialism and Resistance, 1917-2017 (New York: Picador Metropolitan Books, Henry Holt and Company, 2020), 70.

[7] Hildi Hendrickoson, Clothing and Difference (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1996), 8.

[8] Mamoun Candy, “Political Science without Clothes: The Politics of Dress or Contesting the Spatiality of the State in Egypt,” Arab Studies Quarterly, Vol.20, No. 2 (Spring 1998): 91

[9] Edward Said, Orientalism, (New York: Random House, Inc., 1978), 27.

[10] Ted Swedenburg, “Bad Rap for a Neck Scarf?,” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 41(2) (2009): 184-185. doi:10.1017/S0020743809090576.

[11] The sale of the item was available on Urban Outfitter online catalog, described as a “houndstooth scarf.” It was manufactured in China. Today, there is only one kaffiyeh manufacturer in Palestine, the Herbawi factory, a family-run company located in Hebron.

[12] David K. Li, and Caroline Radnofsy, “Louis Vuitton slammed for selling keffiyeh-style scarf,” NBC News, June 4, 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/louis-vuitton-slammed-selling-keffiyeh-style-scarf-n1269629.

[13] Joseph Donica, “Head Coverings, Arab Identity, and New Materialism,” in All Things Arabia: Arabian Identity and Material Culture, eds. Ileana Baird and Hülya Yağcıoğlu (Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2021), 169.

[14] Vogue; New York Vol. 141, Iss. 2, (Jan 15, 1963): 19-23

[15] Vogue; New York Vol. 145, Iss. 4, (Feb 15, 1965): 72-73.

[16] Michelle Malkin, “Rachael Ray, Dunkin' Donuts and the Keffiyeh Kerfuffle,” Townhall, May 28, 2008, https://townhall.com/columnists/michellemalkin/2008/05/28/rachael_ray,_dunkin_donuts_and_the_keffiyeh_kerfuffle-n1083372.

[17] Khalil Gibran, The Madman: His Parables and Poems, (Mineala, New York: Dover Publications, Inc, 2002), 11.

[18] Susan Kaiser, The Social Psychology of Clothing, (New York: Fairchild Books, 1996), vii

[19] Evan Renfro, “Stitched Together, Torn Apart: The Keffiyeh as Cultural Guide,” International Journal of Cultural Studies 21, 6 (2018): 574.

[20] Ian Hodder, Entangled: An Archaeology of the Relationships between Human and Things, (West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 19.

[21] Hodder, Entangled, 64.

[22] Etel Adnan, Shifting the Silence.

[23] Khaled Beydoun https://khaledbeydoun.com.

Appendix: A Chronology of Palestinian History

- 1917: Britain conquers Palestine from the Ottomans.

- 1920: San Remo Allied Powers conference grants Palestine to Britain as a mandate.

- November 29, 1947: End of the British mandate. The United Nations propose a Partition Plan for Palestine recommending the creation of two states, one Jewish and one Arab.

- May 14, 1948: David Ben-Gurion, head of the Jewish Agency, proclaims the establishment of the State of Israel.

- May 15, 1948: Final withdrawal of British forces.

- May 16, 1948: The Arab-Israeli War begins.

- February and July 1949: A temporary frontier is fixed between Israel and its neighbors. In Israel, the war is remembered as the War of Independence. In the Arab world, it came to be known as Al Nakbah, the Catastrophe.

- 1959: Yasser Arafat forms Fatah fighting group.

- 1964: The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) is formed.

- June 1967: Six-Day War.

- 1969: Yasser Arafat takes over PLO leadership.

- 1970: Tension increases over the strength of the PLO in Jordan and leads to the Black September clashes with Jordanian forces, driving the PLO into exile in southern Lebanon.

- October 6 1973: Yom Kippur/Ramadan War: A coalition of Arab nations, led by Egypt and Syria, launches a surprise attack on Israel. Israel raids PLO bases in Lebanon.

- September 17, 1978: Camp David Peace Treaty. Israel pledges to expand Palestinian self-government in the West Bank and Gaza, and to return the Israeli-occupied Sinai Peninsula to Egypt.

- June 5, 1982: Israel invades Lebanon to expel the PLO leadership and its bases from Beirut. PLO leadership moves to Tunisia, where it remains until it moves to Gaza in 1994.

- December 1987: First Intifada uprising begins in Palestinian Territories. The Muslim Brotherhood in Gaza forms the Hamas movement.

- September 1993: Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat sign Oslo Declaration to plot Palestinian self-government and formally end the First Intifada.

- 2000-2001: Talks between Israeli Labour Prime Minister Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat break down over the timing and extent of a proposed Israeli withdrawal from the West Bank. Second Intifada begins in September 2000.

- November 2004: Yasser Arafat dies in hospital in France.

- January 2005: Mahmoud Abbas becomes head of the PLO.

- February 2005: Sharm El Sheikh Summit, end of the second Intifada.

- 2008 - 2012: A series of deadly operations are launched by Israelis and Palestinians leaving many casualties (military and civilians) on both sides.

- December 2017: U.S. President Donald Trump recognizes Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

- November 2019: U.S. no longer considers Israeli settlements on the West Bank to be illegal.

- May 2021: Israeli police raids al-Aqsa Mosque. Hamas fires rockets toward Tel Aviv for the first time in years, prompting Israel to retaliate with airstrikes. The fighting is the fiercest since at least 2014, with more than 200 killed in Gaza alone.

- October 2023: 50 years after the beginning of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, Hamas strikes a coordinated surprise offensive on Israel known as Operation Al-Aqsa Flood. The large-scale assault occurred in the early morning hours. Hamas militants breached the Gaza-Israel barrier, attacking, killing, and taking Israeli civilians hostages into the Gaza Strip. Israel formally declares war on Hamas one day later and puts the Gaza strip under siege, forcing hundreds of thousands of Palestinians out of their homes. The siege continues. As humanitarian conditions in Gaza worsen by the day, war rages on. The total number of casualties on both sides has reached more than 6000 people.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics