Fiona Dieffenbacher is an Associate Professor of Fashion at Parsons School of Design. Author of Fashion Thinking: Creative Approaches to the Design Process (Bloomsbury, 2020), her research is located at the intersection of dress, embodiment, and spirituality, focusing on the 'space in between' theory and practice.

Fig 1: The Principles, Aims, and Approaches of Critical Pedagogy (Adapted from Seal and Smith 2021).

Fig 1: The Principles, Aims, and Approaches of Critical Pedagogy (Adapted from Seal and Smith 2021).“Education should empower individuals to question and transform the world around them” - Paulo Freire

This paper is grounded in Critical Pedagogy (CP) that embraces the belief that educators should encourage learners to examine power structures and patterns of inequality through an awakening of critical consciousness in pursuit of emancipation from oppression. Through the landmark text Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire became widely regarded as the founder of critical pedagogy. A central tenet of Freire’s critical pedagogy is "conscientizacao," or critical awareness that precedes action. Critical awareness begins when learners become aware of sociopolitical inequities and then take action to mitigate those contradictions. Freire was critical of the “banking” model of education, which views learners as empty, inferior, passive recipients of a teacher’s knowledge and argued that this approach discourages critical thinking and dehumanizes both the learner and the teacher. Alternatively, Freire advocated for a “problem-posing education" fueled by dialogue where:

- Learners are agentic – they have the power to control their own goals, actions, and destiny

- Learning takes place through problem solving

- Learning should be both theoretical and practical

- Teachers should not be the authoritative distributors of knowledge

- New possibilities emerge when students and teachers are co-learners

- Learning is an endless process of becoming.

In the context of fashion education, these conversations center around dismantling elitist, Western-dominant beauty standards and consumption-driven values in order to empower students to recognize and center other ways of knowing, as well as establish sustainable and ethical values and inclusive approaches to designing for all bodies, abilities, and communities.

Undoing Inbuilt Perceptions

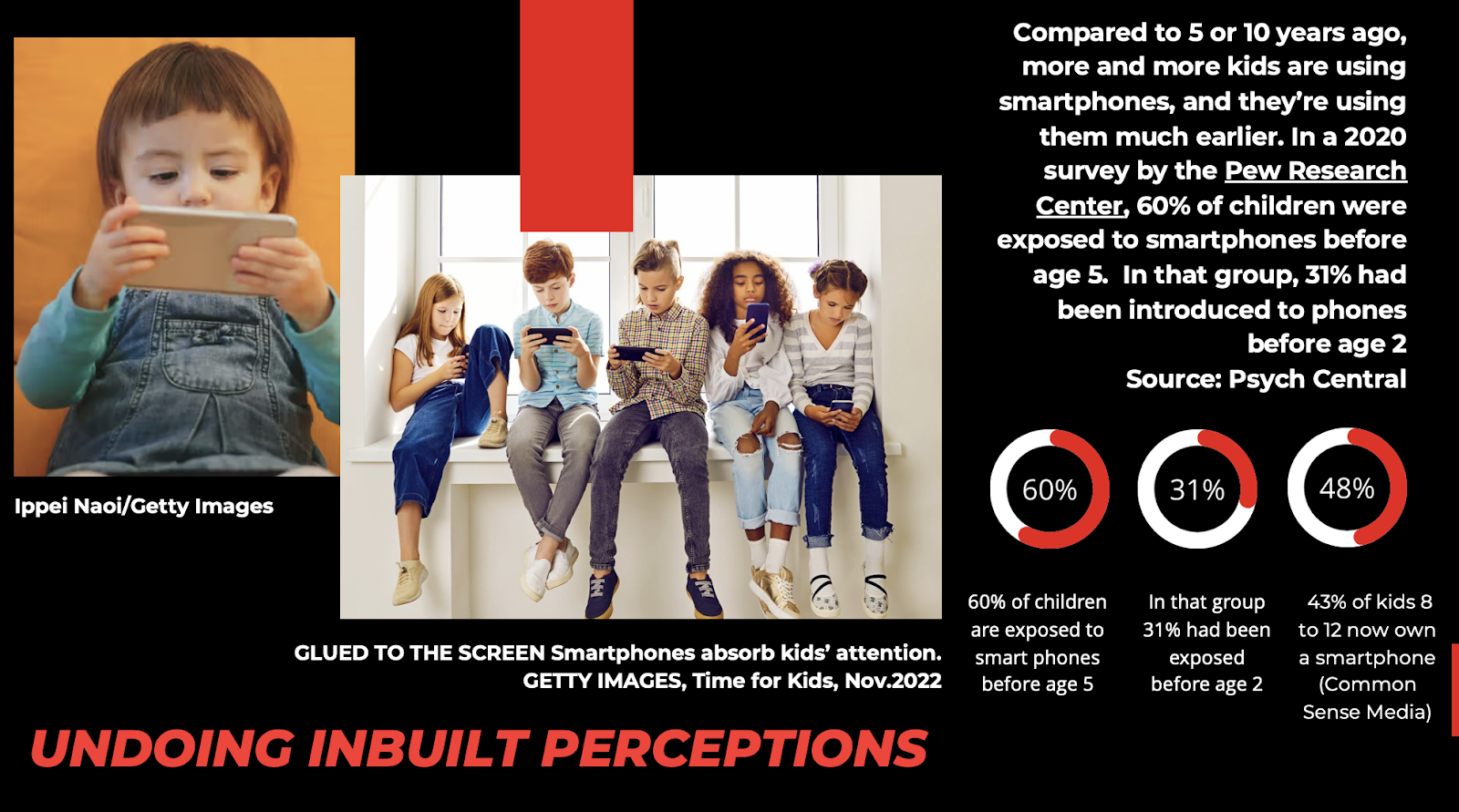

Within the classroom setting, when we engage in tough conversations with our students, it can often feel like a game of fashion bait and switch as the preconceptions and perceptions of fashion they arrived with are challenged. Students feel convicted, and in some instances ashamed, at recognizing their own biases for the first time. This work is made more difficult due to the sheer volume of media they have consumed by the time they arrive in a higher education setting.

According to a survey by Pew research in 2020, sixty percent of children are exposed to smartphones before the age of five (Figure 2). [1] In that group, 31% had been introduced to phones before age two and 48% of kids aged 8–12 own a smartphone. This means that by the time students enter our classrooms as freshmen they have been consuming media for a decade and half. If they are interested in fashion, they will likely have consumed images and formed preconceived notions of what fashion is and who it is and is not for. They will have watched every episode of “Project Runway,” “Next in Fashion,” and “Making the Cut,” formed the habit of feverishly checking Vogue Runway each season, reading the collection reviews and following their favorite designers on Instagram and TikTok.

This work of undoing is comprehensive and complex at the institutional level and is dependent upon the university’s willingness to interrogate its approach to recruitment, admission strategies, and selection processes and at the program level to review and revise its course material (Figure 3).

Key questions to consider as we undertake this work include:

![]() Fig 3: Diagram- Undoing Barriers to Entry.

Fig 3: Diagram- Undoing Barriers to Entry.

History, Legacy, and Brand Identity

Parsons’ reputation as a powerhouse for graduating top fashion design talent extends to over a century. Established in 1896 as Chase School and later renamed Parsons School of Design in 1941 after Frank Alvah Parsons, the school launched the first fashion design program in the U.S in 1904 (originally named costume design). Today Parsons is ranked #1 in the U.S and among the top 3 art and design schools worldwide. The sequence of selected images in Figure 4 below are taken from the historical timeline on the Parsons' website showing key milestones that represent a particular view of fashion at a particular time.

Key questions to consider as we undertake this work include:

- How / does maintaining the perception of the ‘brand’ play into decision-making?

- What are we protecting? What are we afraid to let go of?

- In what ways do our strategies for recruitment need to be revised in order to ensure more access to underrepresented communities?

- What has to change for this to become a reality?

- In terms of admissions, do portfolio requirements communicate that a diverse range of perspectives on fashion are welcome?

- Are the requirements representative of a range of practices?

- Is the makeup of committees diverse in order to ensure representation and equity in decision-making?

- Are all cultural perspectives and aesthetics celebrated within internal selection processes for scholarships, awards, shows, etc.?

- Do syllabi and course learning outcomes represent inclusive pedagogical approaches to fashion?

- Are all histories represented beyond a eurocentric model?

- What harmful stereotypes are we perpetuating?

Fig 3: Diagram- Undoing Barriers to Entry.

Fig 3: Diagram- Undoing Barriers to Entry.History, Legacy, and Brand Identity

Parsons’ reputation as a powerhouse for graduating top fashion design talent extends to over a century. Established in 1896 as Chase School and later renamed Parsons School of Design in 1941 after Frank Alvah Parsons, the school launched the first fashion design program in the U.S in 1904 (originally named costume design). Today Parsons is ranked #1 in the U.S and among the top 3 art and design schools worldwide. The sequence of selected images in Figure 4 below are taken from the historical timeline on the Parsons' website showing key milestones that represent a particular view of fashion at a particular time.

Fig 4: Parsons’ historical timeline showing key milestones between 1951–2008.

“When faculty give up our positions of power and engage students as active participants whose contributions are valued we create an environment where we learn from one another.”

The first image, from 1951, depicts the celebrated French couturier Christian Dior attending Parsons classes in Paris to critique fashion design projects and share his innovative construction techniques with students. Previously, Jeanne Lanvin, Elsa Schiaparelli, and Jean Patou served as guest critics, reinforcing the belief that Paris was the epicenter of fashion. By contrast, the next image, from 1979, of the iconic Fashion Avenue street sign signifies the establishment of the fashion campus in the heart of the garment district, underscoring its ties to the American fashion industry. The following image shows Marc Jacobs, who won the prestigious CFDA Perry Ellis award for emerging talent in 1984 and launched his career only three years after graduation and one year after launching his eponymous new line. A hallmark of the BFA Fashion Design program is graduates who launch their own labels and go on to become leaders in the fashion industry, and this is one of the many reasons why so many aspiring talents seek out a Parsons education today and why so many fashion brands want to hire them.

Back cover, The School of Fashion, 30 Parsons Designers by Simon Collins (Assouline, 2014).

In 2003, Designers Sophie Buhai and Lisa Mayock launched Vena Cava after graduation. Speaking of their experience studying in New York, they state, “This is the epicenter of fashion and culture. Going out in the city, seeing what people are wearing and what’s going on, that's what fashion is. That’s a big advantage of going to fashion school in New York, you just are exposed to all the newness around you.” (Figure 5) [2] These remarks represent a particular perception of fashion and New York at a time when Parsons’ approach to fashion design education was predicated on training students for careers on Seventh Avenue. As a result, brands came to expect a specific type of graduate who not only excelled in design, sketching, sewing, construction, and pattern-making, but who exemplified what came to be known as the “Parsons Aesthetic.” While these skill sets are undeniably essential, the perpetuation of a singular design identity is not.

Building on the legacy of notable alumna Claire McCardell, credited with creating American Sportswear, Parsons graduates captured what this meant for the twenty-first century. The fashion program, housed at 550 Seventh Avenue, was fully immersed in the then-vibrant life of the garment center that has since diminished with sampling and production moving overseas.

Building on the legacy of notable alumna Claire McCardell, credited with creating American Sportswear, Parsons graduates captured what this meant for the twenty-first century. The fashion program, housed at 550 Seventh Avenue, was fully immersed in the then-vibrant life of the garment center that has since diminished with sampling and production moving overseas.

An Evolution of Pedagogy

The final image shown in the timeline from 2008 in Figure 4 shows a diagram representing Parsons’ reorganization of its individual programs into five schools and the emergence of the School of Fashion. As part of this structural re-design, the school moved downtown to the new University Center on Fifth Avenue and 13th Street in 2013. This geographic relocation from the Garment Center was symbolic in several ways as it resituated the school within the university campus and offered students and faculty a more integrated experience working alongside peers across programs within Parsons and The New School.

Fig 6: Parsons Timeline showing key milestones between 2016- 2023.

Fig 6: Parsons Timeline showing key milestones between 2016- 2023.

The four images in Figure 6 represent an evolution in pedagogy at Parsons that began in 2010 with a reimagining of its undergraduate curriculum. During this time within the newly formed School of Fashion, definitions of what fashion is and who it is for were expanded. In 2016, Grace Jun introduced her inclusive fashion and tech initiative, Open Style Lab at Parsons, as an elective course where students co-designed garments with clients representing a range of abilities. In 2018, students across Parsons participated in an elective course where they redesigned the hospital gown in collaboration with health-wear company Care+Wear and support from AARP that encouraged students to make connections between fashion, health, and age. In 2019, the BFA Fashion Design program showcased the work of the graduating class in “The People’s Runway” on 13th Street offering a democratized, fully inclusive experience where every student showed one look on a model of their choice. These examples demonstrate the shift towards a more inclusive and expansive view of fashion and began laying the foundation for change. In 2021, Ben Barry was appointed dean of the School of Fashion and a vision working group was formed, made up of faculty, staff, and students who reviewed feedback solicited via a survey across key stakeholders (students, alumni, part-time and full-time faculty, staff, and key external partners). This work informed the vision and values for the School of Fashion that frames our approach to pedagogy and practice today. These were added to the landing page on the school’s website for visibility:

The opening statement on the landing page of the School of Fashion website underscores our commitment to inclusive pedagogy:

This offers critical context for the ongoing work of undoing and embedding inclusive pedagogical practices across our curriculum. The final image in the sequence in Figure 6 shows a fat model walking alongside a disabled model in a wheelchair on the runway at the MFA Fashion Design and Society graduate show held at the Brooklyn Museum in 2023.

As faculty committed to the deep work of undoing, we need to acknowledge that this work must first begin with us. Teaching is not a static practice—as the world changes, our approach to pedagogy must also evolve to meet the current challenges of our time. The responsibility for establishing an inclusive fashion pedagogy requires a commitment to authenticity that encourages us to own our mistakes and interrogate our biases along with a willingness to be vulnerable in the classroom as we seek to model the messiness of ‘undoing’ in our own lives. This deeply personal work of introspection is critical if we are to lead authentic conversations in the classroom. Moving away from traditional modes of delivery, referred to as the ‘banking model’ of education whereby faculty position themselves as experts disseminating knowledge to students as passive recipients, when faculty give up our positions of power and engage students as active participants whose contributions are valued we create an environment where we learn from one another. [3] Recognizing that our students come with discrete knowledge, the classroom becomes a space for an exchange of ideas where we experience deep personal change as we move through this process of transformation together.

Reflecting upon my evolution as a fashion educator over the past 20 years, I have had to contend with how my own biases show up within my pedagogy. This is ongoing work of undoing and unlearning that as educators we all need to be earnestly invested in. In 2013, my initial goal in writing my textbook Fashion Thinking: Creative Approaches to the Design Process was to enable students to recognize their own methodology and ways of thinking within the context of the design process. It sought to move away from formulaic approaches to teaching fashion design that perpetuate sameness across outcomes. By presenting a range of projects and perspectives from the field of fashion, Fashion Thinking pushes students to consider new ways of investigating their approach to and understanding of fashion design as a critical practice. Students are introduced to a number of examples that challenge them to think critically about their own work; to develop authentic research trajectories that will inform their design codes and language. They are discouraged from looking to existing fashion for inspiration and are instead encouraged to translate their own research via a process of deep investigation in order to drive innovation forward. As I revisited the text for the second edition my opening remarks in the introduction still held true:

![]() Fig 7: Fashion Thinking, Creative Approaches to the Design Process, Fiona Dieffenbacher (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Fig 7: Fashion Thinking, Creative Approaches to the Design Process, Fiona Dieffenbacher (Bloomsbury, 2020).

In 2020, I updated the second edition to emphasize examples of inclusive design practice such as Camilla Chiraboga's BFA thesis project entitled veº (from the Spanish word ‘to see’) that documents her process working with two blind brothers as well as her participation in the Care + Wear hospital gown design project. Interviews with educators, designers, and professionals in the field cover a range of critical topics including Sustainability and Zero-waste design (Timo Rissanen and Yeohlee Teng); Universal Design (Grace Jun / Open Style Lab); Fashion Journalism, Humanitarianism, and Body Positivity (Mickey Boardman, PAPER Magazine); Genderless Design + Socio-political Awareness (Siyung Qu and Haoran Li, Private Policy); and Design + Labor (Christina Moon). Sara Kozlowski, CFDA’s Vice President of Program Strategies / Education & Sustainability Initiatives highlights three projects from Parsons alum that promote social justice as a driving force for design: GENUSEE by Ali Rose Overbake, FFORA by Lucy Jones, and ADIFF by Angela Luna. My goal in highlighting these perspectives with each of the projects was to underscore the values that drive design, moving us away from viewing fashion design as a merely superficial practice solely based on aesthetics, but a critical discipline that can (and must) facilitate change.

Teaching Notes: Design Studio 1

The following project is an example of how critical pedagogy is applied within the classroom in a fashion design context.

Design Studio 1 is part of a suite of three courses including Creative Technical Studio 1 and Visual Communication Studio 1. Faculty share the same cohort across these sections and, with the goal of creating a common pedagogical framing for the course, we co-authored the following statement that was included in all syllabi:

WEEK 1: The overarching theme for the semester was “The Body,” and I framed the first project with the following key questions:

These questions are deliberately open-ended and require students to think through their answers from their own positions without imposing any external definitions or ideas.

Students were also given a pre-reading prior to the first class:

The objective of the project framing is to allow students to question societal norms and power structures within the fashion system; to critically engage with content (reading and video assignments), and to make connections between personal experiences and broader contexts. The aim is not only to impart knowledge but to foster critical thinking and application, whereby students are encouraged to use the knowledge they gain to challenge the status quo and make a positive impact in the fashion industry. This aspect of critical pedagogy focuses on empowerment and action, not just understanding. It encourages students to question—to become active and critical thinkers who do not merely accept knowledge as it is presented but rather question it and form their own ideas.

- Community: To create a safe and collaborative school culture, we celebrate the diverse identities, perspectives, experiences, and worldviews of our students, faculty, staff, and alumni.

- Decolonization: We challenge and reimagine hierarchies and colonial practices and standards and commit ourselves to ethical modes of learning and expression that foster just relationships with one another and with the planet.

- Belonging: We are at our best when we all can show up as ourselves, learning with empathy, respect, and humility; challenging our biases; and expanding our own awareness while reshaping the prevailing narratives of the fashion industry.

-

Equity: We intentionally broaden access and provide necessary support to groups historicallly and currently marginalized by fashion education and the industry in order to redistribute power and foster justice. One way we foster access is though the Parsons Disabled Fashion Student Program, a recruitment, scholarship, and mentorship initiative for Disabled Fashion Design students.

- Accountability: We value transparency and strive to learn from our mistakes. We are responsible for our actions, our words, and our impact in the classroom, the community, and the world.

The opening statement on the landing page of the School of Fashion website underscores our commitment to inclusive pedagogy:

“Parsons’ School of Fashion leads the industry into a future where access, inclusion, equity, and sustainability are the standard. We cultivate a fashion community within creative, thoughtful, caring, and multidisciplinary learning spaces to foster social, economic, and climate justice…Our students, faculty, and staff are committed to bringing about lasting change in the industry by supporting Indigenous resurgence; honoring the beauty of all bodies; and living in harmony with animals and the earth in ways that advance climate justice.”

This offers critical context for the ongoing work of undoing and embedding inclusive pedagogical practices across our curriculum. The final image in the sequence in Figure 6 shows a fat model walking alongside a disabled model in a wheelchair on the runway at the MFA Fashion Design and Society graduate show held at the Brooklyn Museum in 2023.

The Work Begins with Us!

As faculty committed to the deep work of undoing, we need to acknowledge that this work must first begin with us. Teaching is not a static practice—as the world changes, our approach to pedagogy must also evolve to meet the current challenges of our time. The responsibility for establishing an inclusive fashion pedagogy requires a commitment to authenticity that encourages us to own our mistakes and interrogate our biases along with a willingness to be vulnerable in the classroom as we seek to model the messiness of ‘undoing’ in our own lives. This deeply personal work of introspection is critical if we are to lead authentic conversations in the classroom. Moving away from traditional modes of delivery, referred to as the ‘banking model’ of education whereby faculty position themselves as experts disseminating knowledge to students as passive recipients, when faculty give up our positions of power and engage students as active participants whose contributions are valued we create an environment where we learn from one another. [3] Recognizing that our students come with discrete knowledge, the classroom becomes a space for an exchange of ideas where we experience deep personal change as we move through this process of transformation together.

Fashion Thinking

Reflecting upon my evolution as a fashion educator over the past 20 years, I have had to contend with how my own biases show up within my pedagogy. This is ongoing work of undoing and unlearning that as educators we all need to be earnestly invested in. In 2013, my initial goal in writing my textbook Fashion Thinking: Creative Approaches to the Design Process was to enable students to recognize their own methodology and ways of thinking within the context of the design process. It sought to move away from formulaic approaches to teaching fashion design that perpetuate sameness across outcomes. By presenting a range of projects and perspectives from the field of fashion, Fashion Thinking pushes students to consider new ways of investigating their approach to and understanding of fashion design as a critical practice. Students are introduced to a number of examples that challenge them to think critically about their own work; to develop authentic research trajectories that will inform their design codes and language. They are discouraged from looking to existing fashion for inspiration and are instead encouraged to translate their own research via a process of deep investigation in order to drive innovation forward. As I revisited the text for the second edition my opening remarks in the introduction still held true:

“Fashion has to reinvent itself beyond its own stereotype. To accomplish this we need to foster a generation of designers who think differently about the world they inhabit and employ universal design principles within their methodology and practice.” [4]

Fig 7: Fashion Thinking, Creative Approaches to the Design Process, Fiona Dieffenbacher (Bloomsbury, 2020).

Fig 7: Fashion Thinking, Creative Approaches to the Design Process, Fiona Dieffenbacher (Bloomsbury, 2020).In 2020, I updated the second edition to emphasize examples of inclusive design practice such as Camilla Chiraboga's BFA thesis project entitled veº (from the Spanish word ‘to see’) that documents her process working with two blind brothers as well as her participation in the Care + Wear hospital gown design project. Interviews with educators, designers, and professionals in the field cover a range of critical topics including Sustainability and Zero-waste design (Timo Rissanen and Yeohlee Teng); Universal Design (Grace Jun / Open Style Lab); Fashion Journalism, Humanitarianism, and Body Positivity (Mickey Boardman, PAPER Magazine); Genderless Design + Socio-political Awareness (Siyung Qu and Haoran Li, Private Policy); and Design + Labor (Christina Moon). Sara Kozlowski, CFDA’s Vice President of Program Strategies / Education & Sustainability Initiatives highlights three projects from Parsons alum that promote social justice as a driving force for design: GENUSEE by Ali Rose Overbake, FFORA by Lucy Jones, and ADIFF by Angela Luna. My goal in highlighting these perspectives with each of the projects was to underscore the values that drive design, moving us away from viewing fashion design as a merely superficial practice solely based on aesthetics, but a critical discipline that can (and must) facilitate change.

Teaching Notes: Design Studio 1

The following project is an example of how critical pedagogy is applied within the classroom in a fashion design context.

Shared Faculty Ethos

Design Studio 1 is part of a suite of three courses including Creative Technical Studio 1 and Visual Communication Studio 1. Faculty share the same cohort across these sections and, with the goal of creating a common pedagogical framing for the course, we co-authored the following statement that was included in all syllabi:

“With inclusivity as the driver for this project, we will bring our whole selves and lived experiences into this foundational community-building exploration of the body. Project 01 will center around the introspection and reflection of lived experiences of the body through deep research, experimentation and dialogue.”

WEEK 1: The overarching theme for the semester was “The Body,” and I framed the first project with the following key questions:

- What is fashion?

- Who is fashion for?

- What is fashion’s future?

These questions are deliberately open-ended and require students to think through their answers from their own positions without imposing any external definitions or ideas.

Students were also given a pre-reading prior to the first class:

- Steele, Valerie, “Fashion Future.” In: the end of fashion_ > Clothing And Dress In The Age Of Globalization, ///edited by Adam Geczy and Vicki Karaminas///, London, New York, Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2019

The objective of the project framing is to allow students to question societal norms and power structures within the fashion system; to critically engage with content (reading and video assignments), and to make connections between personal experiences and broader contexts. The aim is not only to impart knowledge but to foster critical thinking and application, whereby students are encouraged to use the knowledge they gain to challenge the status quo and make a positive impact in the fashion industry. This aspect of critical pedagogy focuses on empowerment and action, not just understanding. It encourages students to question—to become active and critical thinkers who do not merely accept knowledge as it is presented but rather question it and form their own ideas.

Fig 8: Design Studio 1: Project 01: The Body - Key questions.

Fig 8: Design Studio 1: Project 01: The Body - Key questions.PROJECT FRAMING (for students): Your perspective on fashion is informed by the intersection of various subject positions (the preferred term used by cultural theorist Susan Kaiser). By understanding these positions, you will begin to interrogate how these inform your fashion practice. You are encouraged to situate your work within the broader context of existing theories and to identify key areas or issues that you are passionate about and are uniquely equipped to address based on your strengths and positionality. As fashion designers, you are encouraged to develop an inclusive approach to considerations of the body. You will critique the existing fashion system and propose new methods that move away from default, ableist modes of design. Methods should result in design provocations that seek to redefine historical, stereotypical representations of beauty towards the establishment of more inclusive design practices and propositions.

Assigned readings:

Based on the Kaiser readings, the students were asked to create intersectional diagrams to facilitate understanding of the various positions they hold that might influence their perspectives as fashion designers.

TEACHING NOTE: The goal of the four questions below is to encourage students to consider internal and external perspectives and move them towards a set of actions and applications to their own work.

KEY CONTEXT : Questions to consider:

WEEK 2: (PRE) CONCEPTIONS OF BEAUTY

Assigned readings:

-

Kaiser, Susan B. “Fashion and Culture: Cultural Studies.” In Fashion Studies in: Fashion and Cultural Studies, pp: 1-27. London: Berg, 2012.

- Kaiser, Susan B. “Intersectional and Transnational Fashion Subjects.” In Fashion Studies in: Fashion and Cultural Studies, pp: 28-51 London: Berg, 2012.

Based on the Kaiser readings, the students were asked to create intersectional diagrams to facilitate understanding of the various positions they hold that might influence their perspectives as fashion designers.

TEACHING NOTE: The goal of the four questions below is to encourage students to consider internal and external perspectives and move them towards a set of actions and applications to their own work.

KEY CONTEXT : Questions to consider:

- Perspective [Personal/Individual] What does it mean to be “EMBODIED”?

- Perspective [Global/Collective] What are your thoughts on the representation of bodies in fashion?

- Action [Goal] What is your role in responding to or addressing the issues you have identified?

- Application [Design] - How will you apply knowledge from the readings, documentaries, and fashion theory to inform your own ways of working (methodologies) in new ways?

WEEK 2: (PRE) CONCEPTIONS OF BEAUTY

Fig 9: Project Framing week 2 (Pre) Conceptions of Beauty.

Fig 9: Project Framing week 2 (Pre) Conceptions of Beauty.KEY QUESTIONS:

FOR STUDENTS: Questions to consider when preparing your reading responses and contributions to class discussions:

- What is beauty?

- Who decides?

FOR STUDENTS: Questions to consider when preparing your reading responses and contributions to class discussions:

- Do you agree/disagree or relate with the perspectives being presented? Why or why not?

- What preconceptions or biases arise for you and how do you plan to address these?

- What role is design contributing (or not)? What changes would you propose?

Fig 10: Week 2 (Pre) Conceptions of Beauty - Assigned videos and readings.

Fig 10: Week 2 (Pre) Conceptions of Beauty - Assigned videos and readings.VIEW:

READ:

TEACHING NOTE: These readings and documentaries centered on Barbie given the launch of the movie in 2023. I utilized this to generate dialogue around the controversial history of the doll in the context of the stereotypical beauty and body standards it promoted as well as its evolution beyond these to more inclusive representations. *Readings and assignments are regularly updated in alignment with current topics.

WEEK 3: THE DISABLED BODY

VIEW: I Feel Sexy In My Disabled Body | Living Differently (Alex Darcy)

READ:

![]() Fig 11: Image of Mural Empathy Map: Alex Darcy.

Fig 11: Image of Mural Empathy Map: Alex Darcy.

TEACHING NOTES: CLASS EXERCISE: MURAL EMPATHY MAP: After viewing the video by disability advocate Alex Darcy (@Wheelchair_rapunzel), students were tasked to engage with her Instagram posts and document key statements via Post-it notes on a mural board under the following four headings : What does she say? How does she feel? What does she think? What does she do? The goal of this exercise was to move students away from assumptions and judgments about disabled folks, towards a posture of understanding and empathy. The outcome of the class discussion exposed internal biases and ableism and began to dismantle stereotypes, producing greater awareness and empathy.

WEEK 4: THE FAT BODY

VIEW:

READ:

Dismantling Fat Phobia

This famous quote by Karl Lagerfeld is just one example of fat phobia that is pervasive throughout the fashion industry. The image in Figure 12 from Italian designer Alessandro Dell'Acqua’s show at Paris Fashion Week in 2015 represents the all too familiar march of thin white models down the runway in the finale.

![]() Fig 12: Italian designer Alessandro Dell'Acqua,Paris Fashion Week, 2015 CHARLES PLATIAU/REUTERS.

Fig 12: Italian designer Alessandro Dell'Acqua,Paris Fashion Week, 2015 CHARLES PLATIAU/REUTERS.

- On Beauty

- Tiny Shoulders: Rethinking Barbie: (Official) A Hulu Original Documentary, 2018, in comparison to the Barbie © movie 2023.

READ:

- “Addressing the Body”, The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Modern Social Theory, Joanne Entwistle, 2nd Edition, (Cambridge, UK, 2015). Pp. 6-39.

- Reclaiming our Black Bodies: reflections on a portrait of Sarah (Saartjie) Baartman and the destruction of black bodies by the state” by Itumeleng Daniel Mothoagae

- A Cultural History of Barbie, Smithsonian Magazine, June 2023

- This Barbie Documentary On Hulu Will Make You View The Controversial Doll In A Totally New Way

- Barbie Just Got Even More Inclusive With Its Latest Fashionistas 2020 Collection

TEACHING NOTE: These readings and documentaries centered on Barbie given the launch of the movie in 2023. I utilized this to generate dialogue around the controversial history of the doll in the context of the stereotypical beauty and body standards it promoted as well as its evolution beyond these to more inclusive representations. *Readings and assignments are regularly updated in alignment with current topics.

WEEK 3: THE DISABLED BODY

VIEW: I Feel Sexy In My Disabled Body | Living Differently (Alex Darcy)

READ:

- The Unfinished Body: The medical and social re-shaping of disabled young bodies by Janice McLaughlin and Edmond Coleman-Fountain

- My Disabled Body is Not a ‘Burden’- Inaccessibility Is by Aryanna Faulkner

- Strategic Abilities: Negotiating the Disabled Body in Dance by Ann Cooper Albright

- Leading The Inclusion Revolution, These Women Are Bringing Beautiful But Functional Apparel To Millions Of Women With Disabilities by Jane Hanson, Forbes

Fig 11: Image of Mural Empathy Map: Alex Darcy.

Fig 11: Image of Mural Empathy Map: Alex Darcy.TEACHING NOTES: CLASS EXERCISE: MURAL EMPATHY MAP: After viewing the video by disability advocate Alex Darcy (@Wheelchair_rapunzel), students were tasked to engage with her Instagram posts and document key statements via Post-it notes on a mural board under the following four headings : What does she say? How does she feel? What does she think? What does she do? The goal of this exercise was to move students away from assumptions and judgments about disabled folks, towards a posture of understanding and empathy. The outcome of the class discussion exposed internal biases and ableism and began to dismantle stereotypes, producing greater awareness and empathy.

WEEK 4: THE FAT BODY

VIEW:

- The Fat Body (In)Visible, film by Margitte Kristjansson

READ:

- Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body, Susan Bordo, The Regents of the University of California, 2003.

- Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, Roxane Gay, New York, Harper Collins, 2017.

- Fat is Not the Problem, Fat Stigma Is by Linda Bacon and Amee Severson, Scientific American, Jul 8th 2019

- The Fashion Body | SHOWstudio (Selection)

Dismantling Fat Phobia

“These are fat mummies, sitting with their bags of crisps in front of the television saying that thin models are ugly. Fashion is about dreams and illusions and no-one wants to see round women.”

This famous quote by Karl Lagerfeld is just one example of fat phobia that is pervasive throughout the fashion industry. The image in Figure 12 from Italian designer Alessandro Dell'Acqua’s show at Paris Fashion Week in 2015 represents the all too familiar march of thin white models down the runway in the finale.

Fig 12: Italian designer Alessandro Dell'Acqua,Paris Fashion Week, 2015 CHARLES PLATIAU/REUTERS.

Fig 12: Italian designer Alessandro Dell'Acqua,Paris Fashion Week, 2015 CHARLES PLATIAU/REUTERS. Fig 13: A selection of images promoting a wider representation of beauty & bodies in media.

Fig 13: A selection of images promoting a wider representation of beauty & bodies in media.

By contrast, the images in Figure 13 showcase a shift towards more diverse and inclusive representations of beauty and bodies in fashion media.

If fashion schools fail to address the issues and continue to send uncritical graduates out into the industry, then we are responsible for perpetuating problematic beauty standards and harmful stereotypes, upholding unsustainable methods of making and creating and continuing a design narrative that excludes bodies that society and the fashion industry deem undesirable. It is incumbent on fashion educators to begin the dialogue exposing students to existing issues within the fashion system early on their educational journey and challenging them to reconsider who they are designing for and why in order to instill a greater sense of responsibility. Encouraging students to disrupt narrow-minded perceptions of fashion, shifting their mindsets towards building more inclusive practices, will contribute to a more inclusive and less harmful fashion industry. Graduates will move out into the fashion industry as the next generation of designers to challenge the status quo and effect the real change we so desperately want to see. Together, we must commit to this hard but essential work of undoing fashion, simply because there is too much at stake!

Notes: Undoing Preconceived Ideas

[1] Auxier Brooke, Monica Anderson, Andrew Perrin, and Erica Turner. “Children’s Engagement with Digital Devices, Screen Time,” Pew Research Center, (2020). https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/childrens-engagement-with-digital-devices-screen-time/

[2] Simon Collins and Magg Silja. The School of Fashion : 30 Parsons Designers (New York: Assouline 2014).

[3] Paulo Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: The Seabury Press, 1970).

[4] Fiona Dieffenbacher. Fashion Thinking (London: Bloomsbury, 2020).

Additional Resources

Abby Gardner. “Review of ‘Barbie Just Got Even More Inclusive with Its Latest Fashionistas 2020 Collection.’” Glamour (January 28, 2020). https://www.glamour.com/story/barbie-fashionistas-2020-vitiligo-hair-loss-dolls

A Smith and M Seal. “The contested terrain of critical pedagogy and teaching informal education in higher education.” Education Sciences, 11(9) 2021:476. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090476

Emily Tankin. “Review of A Cultural History of Barbie,” The Smithsonian (June 2023) https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/cultural-history-barbie-180982115/

Olivia Truffaut-Wong, n.d. “Review of ‘Hulu’s New Barbie Doc Will Make You View the Controversial Doll in a Totally New Way.’” Bustle (April, 2018). https://www.bustle.com/p/this-barbie-documentary-on-hulu-will-make-you-view-the-controversial-doll-in-a-totally-new-way-8901276

What’s at Stake?

If fashion schools fail to address the issues and continue to send uncritical graduates out into the industry, then we are responsible for perpetuating problematic beauty standards and harmful stereotypes, upholding unsustainable methods of making and creating and continuing a design narrative that excludes bodies that society and the fashion industry deem undesirable. It is incumbent on fashion educators to begin the dialogue exposing students to existing issues within the fashion system early on their educational journey and challenging them to reconsider who they are designing for and why in order to instill a greater sense of responsibility. Encouraging students to disrupt narrow-minded perceptions of fashion, shifting their mindsets towards building more inclusive practices, will contribute to a more inclusive and less harmful fashion industry. Graduates will move out into the fashion industry as the next generation of designers to challenge the status quo and effect the real change we so desperately want to see. Together, we must commit to this hard but essential work of undoing fashion, simply because there is too much at stake!

Notes: Undoing Preconceived Ideas

[1] Auxier Brooke, Monica Anderson, Andrew Perrin, and Erica Turner. “Children’s Engagement with Digital Devices, Screen Time,” Pew Research Center, (2020). https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/07/28/childrens-engagement-with-digital-devices-screen-time/

[2] Simon Collins and Magg Silja. The School of Fashion : 30 Parsons Designers (New York: Assouline 2014).

[3] Paulo Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (New York: The Seabury Press, 1970).

[4] Fiona Dieffenbacher. Fashion Thinking (London: Bloomsbury, 2020).

Additional Resources

Abby Gardner. “Review of ‘Barbie Just Got Even More Inclusive with Its Latest Fashionistas 2020 Collection.’” Glamour (January 28, 2020). https://www.glamour.com/story/barbie-fashionistas-2020-vitiligo-hair-loss-dolls

A Smith and M Seal. “The contested terrain of critical pedagogy and teaching informal education in higher education.” Education Sciences, 11(9) 2021:476. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11090476

Emily Tankin. “Review of A Cultural History of Barbie,” The Smithsonian (June 2023) https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/cultural-history-barbie-180982115/

Olivia Truffaut-Wong, n.d. “Review of ‘Hulu’s New Barbie Doc Will Make You View the Controversial Doll in a Totally New Way.’” Bustle (April, 2018). https://www.bustle.com/p/this-barbie-documentary-on-hulu-will-make-you-view-the-controversial-doll-in-a-totally-new-way-8901276

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Fig 2: Undoing Inbuilt Perceptions, children’s engagement with smartphones.

Fig 2: Undoing Inbuilt Perceptions, children’s engagement with smartphones. Fig 5: Sketches by Vena Cava, The School of Fashion by Simon Collins, 2014, pages 144-145.

Fig 5: Sketches by Vena Cava, The School of Fashion by Simon Collins, 2014, pages 144-145.