Aude Fellay is a writer, researcher, and teacher. She coordinates and teaches theory courses in the MA program in Fashion, Jewellery, and Accessory Design at HEAD-Genève, where she is also engaged in practice-based research. Her writing explores contemporary fashion, image culture, and labor. Her work has been featured in publications such as Dune Journal, Issue Journal, and Revue Faire.

In her landmark book Fashion at The Edge, Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness, Caroline Evans gives weight to fashion design as a form of cultural analysis. [1] In a recent interview with Rosie Findlay about the publication, Evans acknowledges that the book’s method registers as a “sort of mimicry” or “perhaps an echo?” of fashion design’s own operations. [2] From my perspective, as a “theorist” [3] surrounded by practitioners, and in a perpetual struggle against the incessant infantilization of the practice, her writing conveys more than an echo of fashion design. Despite it being theory-heavy, it goes some way in narrowing the gap between theory and practice as institutional categories, by theoretically “testing” the methods of “creative” fashion design. [4] Put differently, it mobilizes fashion design methodologies, which it simultaneously helps to foreground, “assuming an equivalent between the historian and the designer.” [5] As such, the book—and her work more broadly—offers fashion design a form of legitimacy as a mode of inquiry and highlights its specificities in ways that do not reiterate false oppositions between the material and immaterial elements of fashion. What follows, then, is a very brief attempt to point out the significance of Evans’s work not simply as fashion history but as a resource for the further formalization of practice-based research in fashion at a moment when its stakes and formats are being outlined. I have set out to do this in the wake of having almost concluded a two-year long practice-based project at HEAD–Genève (HES-SO). Here—to borrow from the Virgil Abloh playbook—I am “postrationalizing” Evans’s contribution from the standpoint of that project and elaborating on the project itself to highlight ways we might “stay with the practice” as we transform it.

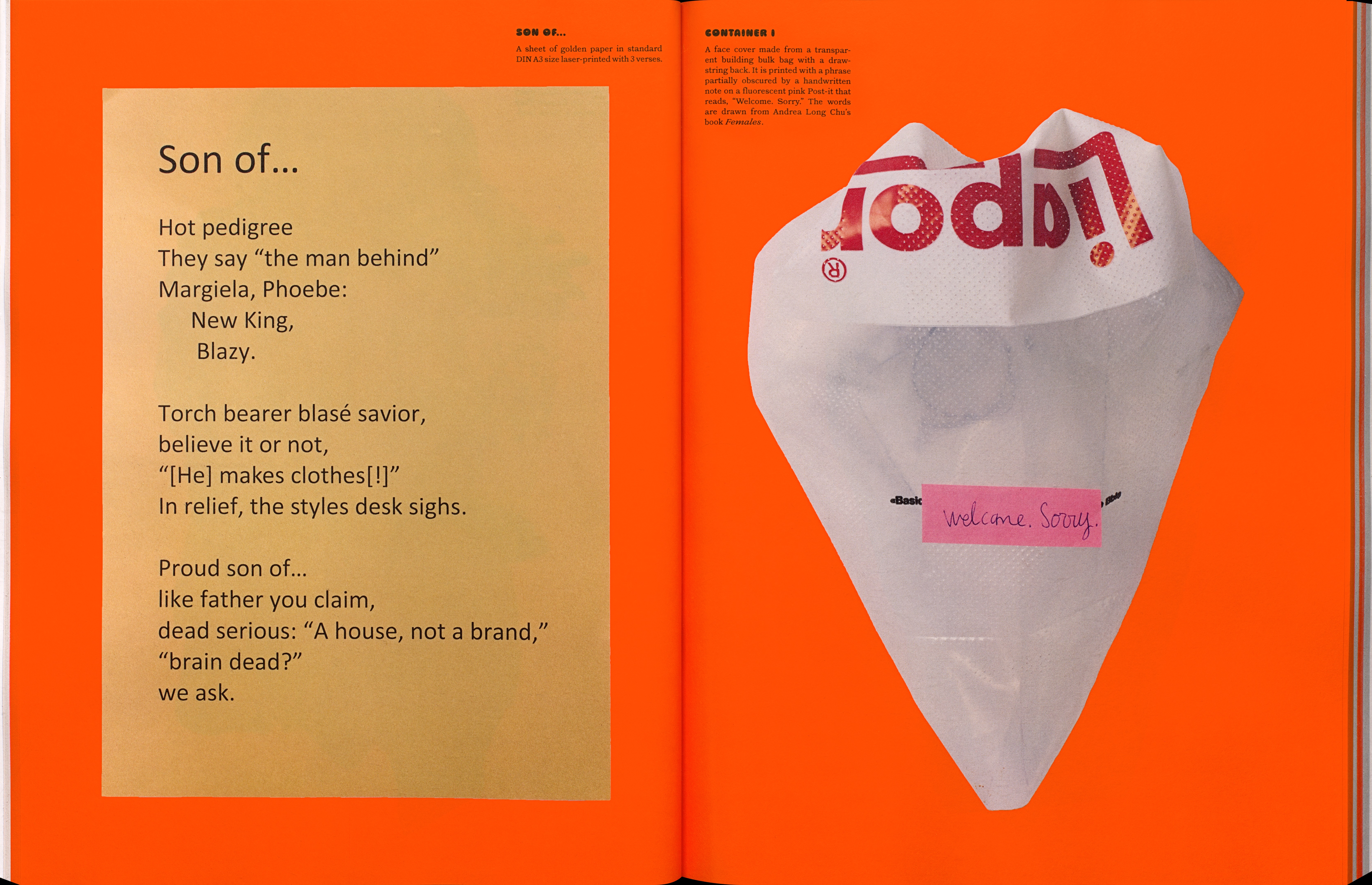

The first edition of Fashion at The Edge. A second edition was released in 2023.

The first edition of Fashion at The Edge. A second edition was released in 2023.The Wall

The hurdles fashion studies faced as it entered the academy have been well documented. [6] The obstacles facing fashion design as it follows the same path—some forty years after the fields of art, design, and architecture did—are even greater. [7] Firstly, practice-based research, regardless of the practice in question, still suffers from a lack of credibility. [8] Additionally, in the case of fashion, its academic field’s increased criticism of fashion design and the fashion industry more broadly have—and justly so—raised serious concerns about the practice itself. [9] This has resulted in both a permission to rethink how fashion is done and a steeper “wall of articulation” for fashion design as research. [9] In other words, the internal and external pressures of criticality and criticism have raised the bar “when it comes to proving [fashion design’s] activities and endeavors are worthwhile.” [10]

It is tempting, in this context, to salvage the practice of fashion design by repackaging it as art. As José Teunissen notes, fashion designers turned researchers have looked to “performances, installations, interventions, films and exhibitions…to replace the classic representations such as the catwalk, the fashion magazine and the fashion campaign,” valuing “the design process and the story above the artefact.” [11] Like Evans, I am uncomfortable with fashion’s strategic alignment with art, not least because, as she puts it, “fashion is plenty interesting enough.” [12] I do, however, understand its logic as a survival strategy for practitioners. In any case, clarifying the specificities of fashion’s practice, in its diverse contexts, is a worthwhile endeavor in light of both a growing interest in practice-based research and art’s more longstanding tradition of artistic research. To this end, I find myself going back to Evans’ work for ways of thinking about fashion design that attend to fashion as a design practice with its own methods, formats, constraints, and contexts.

Top: One of the “iconic” objects we chose as starting points was the Maison Martin Margiela veil. Shown here are examples of artifacts we developed in response. The piece on the left was produced by @knitgeekproject (Valentine Ebner), while the mask on the right was created through the upcycling of garments.

Bottom: The artifacts progressively departed from the original item as the research advanced.

Top: One of the “iconic” objects we chose as starting points was the Maison Martin Margiela veil. Shown here are examples of artifacts we developed in response. The piece on the left was produced by @knitgeekproject (Valentine Ebner), while the mask on the right was created through the upcycling of garments.

Bottom: The artifacts progressively departed from the original item as the research advanced. “I find myself going back to Evans’ work for ways of thinking about fashion design that attend to fashion as a design practice with its own methods, formats, constraints, and contexts.”

A “New” Form of Cultural Analysis

Evans’ Fashion at The Edge, first published in 2003, is “a case study of a method,” which she directs at the work of designers of the late 1990s. [13]Collecting concepts and historical motifs, she moves from present to past, and past to present, to make sense of the ubiquity of spectacle and death in the work of designers such as John Galliano or Alexander McQueen, zooming in on the historical citations that permeate their work. The book homes in on fashion’s material underbelly, contextualizing the anxiety and trauma designs evoked among the large-scale transformations underway at the time: a technological revolution, globalization, a century coming to its conclusion. Her method takes cues from her subject matter: she writes how the designers of which she speaks design. [14] She made this clear at the time, writing that “ragpicking, as well as describing designers’ methods, is also a useful tool for the cultural historian in thinking about fashion today.”[15] In contextualizing her methodological choices and the breadth of the issues addressed, she goes some way in lending fashion design’s “cultural poetics” epistemological weight. [16] She does the latter by way of household names, looking for equivalent methods in the writings of Walter Benjamin (among others). [17]

Like many fashion designers, Evans “thinks through images,” drawing on her own images to illuminate the work of designers—the Benjaminian ragpicker being one of them. She unearths concepts and brings them to bear on fashion to both decipher its meanings and describe its operations. Italo Calvino’s “thinking through images” is an example drawn from another, influential essay of hers, which I have found particularly useful. [18] It is both concrete—it hints at designers’ visual research—and analytically productive. The term can be applied to the fact that designers create garments with an understanding of their narrative or conceptual function within broader compositions—a look and/or a collection. The expression also points to the emblematic quality of the processes and outputs: as Evans argues, images are transformed into objects, and objects into images. In this sense, it points at the central role of “dreamworlds,” not as ad hoc contextualization but as the deliberate materialization of a viewpoint, one that arises from the interaction of a design identity and a specific topic or theme. In many ways, then, her work underscores the specificities of fashion design as it is practiced in our shared context, puts forward concepts through which to apprehend it, and implicitly legitimizes its operations as ways of knowing. [19]

The second “iconic” object was the Louis Vuitton Speedy bag tagged by Steven Sprouse in a collaboration initiated by Marc Jacobs. Shown here, an artifact created in response to the Speedy and the opening chapters of the Vuitton series.

The second “iconic” object was the Louis Vuitton Speedy bag tagged by Steven Sprouse in a collaboration initiated by Marc Jacobs. Shown here, an artifact created in response to the Speedy and the opening chapters of the Vuitton series.“[W]e decided to look critically at our own context (the western fashion and luxury industry), and its golden age (the late 1990s—Evans’ purview), through the viewpoint of some of its ‘iconic’ objects.“

How To?

Granted, the knowledge produced by fashion design in this context is dependent upon the labor of the critic or the cultural historian. It must be inferred from the images and material translations designers conjure. But there are ways for practitioners to uncover that knowledge and reveal the medium’s potential as a mode of inquiry, and there are dissemination formats to be found within fashion design’s own methods. [20] When designer Emilie Meldem and I set out to conduct a practice-based research project, we decided to look critically at our own context (the western fashion and luxury industry), and its golden age (the late 1990s—Evans’ purview), through the viewpoint of some of its “iconic” objects. [21] The icons were fitting emblems for the industry and a manageable starting point for a more wide-ranging, anti-capitalist, and feminist critique of the fashion industry’s extractive nature and normative thrust. These objects were not only “iconic”—or rather, heralded as such by the industry—but evoked central elements of a fashion design practice: a design identity (a “DNA,” if you will), and a know-how or savoir-faire, which raised questions about materials and production. In short, our choice of objects would help us build our own DNA and savoir-faire.

Our research book—a tool commonly used by designers to document their research and process—became both a format for sharing our output and an analytical tool, through which we articulated our critique and postrationalized our design experiments. In it, our engagement with the icons takes the very literal form of a “detective story” (a term that Evans uses, in fact, to characterize the type of cultural analysis shaped by Walter Benjamin’s concept of the trace and fashion design’s ragpicking [22]). The research material is presented as a series of clues to be deciphered through their captions and the objects they correspond to. These materials provide context for both the icons and the artifacts we created in response, which indexed specific aspects of the original icons or embodied our critique of them. While the initial artifacts closely resembled the icons, they became increasingly distinct through successive iterations—a shift shaped, in part, by the evolving framework of the research, as we moved from an initial, “paranoid” reading of the icons, which focused on the economic system and patriarchal order underwriting them, to attempts at yielding “reparative” tools and practices. [23]

The research material was post-rationalized into a series of visual chapters, with captions offering interpretive clues.

The research material was post-rationalized into a series of visual chapters, with captions offering interpretive clues.It was clear to us from the start that to stick with the practice, we would have to design the artifacts on the basis of a design identity, and think of a specific know-how, as well as consider production issues. Our close reading of the Margiela veil and of Maison Margiela’s broader appeal as expressing a desire for collective design structures informed the design identity: we gave up on devising an identity as a duo to test what designing as a collective would actually entail. [24] In short, we took seriously the desires lodged in the stories we tell ourselves about these objects, while exposing their falsities (Margiela operated, like most design studios, hierarchically). We assembled a research team and looked for tools to address asymmetries, and make power visible and accessible within the group. [25] So, while we remained committed to fashion as an existing set of practices, we were equally determined to reshape it, drawing on the counter-hegemonic critiques of the theorists, activists, cultural workers, and practitioners in our lives—many of whom embodied several of these roles. [26]

Artifacts that respond to the Louis Vuitton bag, highlighting its components: the body is made of PVC-coated canvas, while the only leather elements are its handles.

Artifacts that respond to the Louis Vuitton bag, highlighting its components: the body is made of PVC-coated canvas, while the only leather elements are its handles.We extrapolated methods from fashion understood as not simply made of design, narrowly conceived as the making of objects, but a whole host of practices that surround it and enable it. Storytelling, and fashion’s own hybrid language (in our context, Franglais), informed the publication’s structure and tone, for example. From the perspective of practice that is often ridiculed or deemed incapable of critical thought, it was essential that we developed our methods and dissemination formats from within the confines of the practice. In fact, staying with the practice meant devising two final stand-alone objects based on the many artifacts produced. [27] This acted as a productive constraint. It compelled us to confront both practical and theoretical questions, which would have escaped us otherwise: how aesthetic decisions are made when a collective is involved, or what desire and success might look like for us, at both the level of the objects and our own life choices, for instance. A focus on the process alone would have led to different outcomes, arguably more theoretical than applied.

The chapters move from examining the object itself to documenting and reflecting on our partial responses and provisional solutions to the questions it raised.

The chapters move from examining the object itself to documenting and reflecting on our partial responses and provisional solutions to the questions it raised.Fashion research can be both “artistic” and result in concrete changes to the practice itself, providing its specificities and applied dimension are accounted for. Theoretical frameworks can be put to work, and find themselves refined in the process, perhaps especially when theorists and designers collaborate and titles loosen in the process. This is one of the epistemological potentials of (critical) practice-led research at this moment in time: the possibility to act upon the critiques it articulates—to do better in real time. Fashion’s proximity to desire means it is also uniquely positioned to engage in and render desirable projects of making a good life. Perhaps this is what Evans gestured at in a 2020 interview with Susanna Strömquist, where she proposed fashion activism (re)acquainted itself with utopia. [28]

Storytelling played a crucial role in sorting, connecting, and organizing the research material. The research book—designed in collaboration with Sereina Rothenberger and David Schatz of Hammer—is scheduled for publication by Rollo Press in 2026.

Storytelling played a crucial role in sorting, connecting, and organizing the research material. The research book—designed in collaboration with Sereina Rothenberger and David Schatz of Hammer—is scheduled for publication by Rollo Press in 2026.Notes: Thinking Through Fashion (Practically)

[1] Caroline Evans, Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity, and Deathliness (Yale University Press, 2003).

[2] Rosie Findlay, “Revisiting Fashion at the Edge: An Interview with Caroline Evans,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 11, no. 2 (2024): 319-327.

[3] I do not hold the proper credentials, in the context of my own institution, to claim the title. I am PhD-less and a part-time member of staff.

[4] The word is a coded and loaded term that refers to art and design schools of the Global North with associations to the upper echelons of the fashion industry and its capitals.

[5] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 13.

[6] Valerie Steele, “The F Word,” *Lingua Franca* 1, no. 4 (April 1991): 17–20.

[7] For an introduction to the rise of practice-based research in fashion, see Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton “The Politics of Fashion Knowledge between Practice and Theory,” in Fashion Knowledge: Theories, Methods, Practice and Politics, ed. Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton (Intellect Ltd., 2024), 1–11.

[8] Yves Citton, “Ce que la recherche-création fait aux thèses universitaires,” Issue, 15 octobre 2024, https://www.hesge.ch/head/issue/publications/ce-la-recherche-creation-fait-aux-theses-universitaires-yves-citton

[9] The term, borrowed by Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta and Tere Vadén, from Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s work on scientific knowledge and indigenous communities, describes an asymmetrical relationship, or the idea that “the values and phenomena self-evident in communities of the artists may not be self-evident in communities of scientists.” Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta, and Tere Vadén, Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public (Peter Lang, 2014). On fashion studies’ critical turn, see for example Natalya Lusty, “Fashion Futures and Critical Fashion Studies,” Continuum: Journal of Media & Cultural Studies 35, no. 6 (2021): 813-823.

[10] Mika Hannula, Juha Suoranta, and Tere Vadén, Artistic Research Methodology: Narrative, Power and the Public, 67.

[11] José Teunissen, “The Transformative Power of Practice-Based Fashion Research,” in Fashion Knowledge: Theories, Methods, Practice and Politics, ed. Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton (Intellect Ltd., 2024), 25.

[12] Caroline Evans, interview by Susanna Strömquist, “Challenging the Orthodoxy of Fashion from Within,” Critical Fashion Project, 2020, .

[13] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 4.

[14] As Evans notes, designers who were “economically marginal” yet “symbolically central” to the fashion industry in the late ’90s.

[15] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 11.

[16] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 13.

[17] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 12.

[18] Caroline Evans, “Yesterday’s Emblems and Tomorrow’s Commodities: The Return of the Repressed in Fashion Imagery Today,” in Fashion Cultures Revisited, 2nd ed., ed. Stella Bruzzi and Pamela Church Gibson (Routledge, 2013). The article was originally published in 2000, and appears to lay the groundwork for Fashion at The Edge.

[19] Evans’ institutional home is also an art and design school.

[20] Monica Titton has raised the issue of format in practice-based research, noting that “the format of the journal, book, or magazine (...) seems ideally suited for the representation of practice-based research.” See Monica Titton, “Theory as Practice,” in Fashion Knowledge: Theories, Methods, Practice and Politics, ed. Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton (Intellect Ltd., 2024), 27–35.

[21] If our home institution is located on the margins of fashion’s capital (Geneva!), Paris and its luxury brands remain the school’s gold standard.

[22] Evans, Fashion at The Edge, 12.

[23] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading, or, You’re So Paranoid, You Probably Think This Essay Is About You,” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Duke University Press, 2003), 123–151.

[24] This meant conceiving of ourselves first and foremost as a collective, one that happens to design.

[25] The members are artist and designer Camille Farrah Buhler, designer Peter Wiesmann, and writer and couturière Sabrina Clavo. Together, we form the collective Horizons Glaise.

[26] Among them, fashion designer and playwright Marvin M’Toumo, cultural worker and feminist activist Elise Magnenat, and design researcher Jonas Berthod.

[27] We are still in the processing of finalizing these, but they consist of a bag and a poster.

[28] Evans, interview by Strömquist, “Challenging the Orthodoxy of Fashion from Within.”

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics