Anna Espinoza is a legal assistant from Phoenix, Arizona with experience in fashion law, complex litigation, medical malpractice defense and criminal defense. She graduated from Arizona State University in 2022 with dual degrees in Philosophy and Fashion and is an incoming first year law student at ASU’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

“While they may have regarded the right [in one’s personal appearance] as a trifle as long as it was honored, they clearly would not have so regarded it if it were infringed.”

- Justice Thurgood Marshall, Kelley v. Johnson

Dress has an undeniable relationship with politics, culture, values, and identity. Reports about state-imposed clothing bans, whose historical purpose has been to reserve luxurious modes of dress for the nobility, seem to have reached record numbers. This increase begs a close examination of the justification and impact of such bans. When scrutinized, do the bans make moral, logical, and practical sense? Is there not a fundamental, though not absolute, human right to wear what we choose? Shouldn’t the question of fashion be left to the people themselves?

As anthropologist Daniel Miller points out, a depth ontology exists in western academia. There is a prevalent belief that “being—what we truly are—is located deep inside ourselves...in direct opposition to the surface.” [1] Accordingly, someone who cares about what they wear is “shallow,” while a philosopher, or a saint, is “deep,” and thus superior. If we can’t recognize as legitimate or even imagine the deep and meaningful connection some people have to their clothing, it becomes difficult to understand that laws banning clothing are capable of doing real harm and difficult to question whether or not they are just.

The exhibition “The Right to Wear: A Cross-Cultural Exploration of Contemporary Clothing Bans,” first opened in March 2022 at Arizona State University. It includes a selection of banned clothing capturing the spirit of contemporary sartorial prohibitions. The number and the diversity of the bans demonstrates their ability to target different races, religions, genders, sexual orientations, ethnicities, and income brackets.

Our interest in being free to dress as we choose must be weighed against concerns about cultural erasure, security, modesty, ethics, the economy, and the environment. At times, those concerns will and should take precedence over our desire to determine our personal appearance. No doubt we will continue to disagree on the question of whether clothing bans are serving just causes. Nevertheless, each ban deserves a thorough examination in order to make that determination, and none should be relegated to the rank of triviality or consigned to history.

- Justice Thurgood Marshall, Kelley v. Johnson

Dress has an undeniable relationship with politics, culture, values, and identity. Reports about state-imposed clothing bans, whose historical purpose has been to reserve luxurious modes of dress for the nobility, seem to have reached record numbers. This increase begs a close examination of the justification and impact of such bans. When scrutinized, do the bans make moral, logical, and practical sense? Is there not a fundamental, though not absolute, human right to wear what we choose? Shouldn’t the question of fashion be left to the people themselves?

As anthropologist Daniel Miller points out, a depth ontology exists in western academia. There is a prevalent belief that “being—what we truly are—is located deep inside ourselves...in direct opposition to the surface.” [1] Accordingly, someone who cares about what they wear is “shallow,” while a philosopher, or a saint, is “deep,” and thus superior. If we can’t recognize as legitimate or even imagine the deep and meaningful connection some people have to their clothing, it becomes difficult to understand that laws banning clothing are capable of doing real harm and difficult to question whether or not they are just.

The exhibition “The Right to Wear: A Cross-Cultural Exploration of Contemporary Clothing Bans,” first opened in March 2022 at Arizona State University. It includes a selection of banned clothing capturing the spirit of contemporary sartorial prohibitions. The number and the diversity of the bans demonstrates their ability to target different races, religions, genders, sexual orientations, ethnicities, and income brackets.

Our interest in being free to dress as we choose must be weighed against concerns about cultural erasure, security, modesty, ethics, the economy, and the environment. At times, those concerns will and should take precedence over our desire to determine our personal appearance. No doubt we will continue to disagree on the question of whether clothing bans are serving just causes. Nevertheless, each ban deserves a thorough examination in order to make that determination, and none should be relegated to the rank of triviality or consigned to history.

Niqab: MyBatua (polyester georgette)

Abaya: MyBatua (polyester nida)

Hijab: Culture Hijab (polyester chiffon)

France became infamous for initiating federal bans in October of 2010 with the enactment of a law banning “the concealment of one’s face in public,” Law Number 2010-1192. Since then, bans on face coverings have come into effect in Cameroon, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Bulgaria, Italy, Tajikistan, Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Switzerland adopted a face covering ban in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, when masks were mandated to stop the spread of sickness.

In most of the countries that ban the veil, a very small minority of women wear them. But politicians played into Islamophobic stereotypes, claiming they had security concerns about veils and that pressure was being put on women to don them. Widespread dismissal of the significance of the veil and women’s autonomy resulted in the claim that secular states could not allow veils, which would prevent Muslim women from “participation in society.”

Abaya: MyBatua (polyester nida)

Hijab: Culture Hijab (polyester chiffon)

France became infamous for initiating federal bans in October of 2010 with the enactment of a law banning “the concealment of one’s face in public,” Law Number 2010-1192. Since then, bans on face coverings have come into effect in Cameroon, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville, Bulgaria, Italy, Tajikistan, Austria, Denmark, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. Switzerland adopted a face covering ban in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, when masks were mandated to stop the spread of sickness.

In most of the countries that ban the veil, a very small minority of women wear them. But politicians played into Islamophobic stereotypes, claiming they had security concerns about veils and that pressure was being put on women to don them. Widespread dismissal of the significance of the veil and women’s autonomy resulted in the claim that secular states could not allow veils, which would prevent Muslim women from “participation in society.”

Miniskirt: Forever 21 (polyester)

Miniskirt: Forever 21 (polyester)V-neck t-shirt: Bozzolo (cotton and spandex)

While short skirts had existed in many forms across the world, it was the diffusion of miniskirts in the late 1960s that arguably caused the most upset and eventually resulted in now-defunct bans in Namibia, Malawi, and Uganda. Swaziland’s Crimes Act of 1889, however, is still interpreted as a miniskirt ban. It threatens a “fine of 600 rand or imprisonment for 2 years” as a punishment for “enticing or soliciting immoral acts by words, signs…or in any other way whatsoever” and punishment for anyone who “knowingly aids or facilitates the commission of immoral acts; or is a person of notoriously immoral character and exhibits himself in indecent dress or manner at any door or window or within the view of any public street or place.”

Activists struggle against the dangerous belief that European miniskirts are a sexual invitation and that they cause high rates of assault and even a higher rate of HIV/AIDS infection. Implicit in the argument about the miniskirt ban is the question of the meaning of modesty and decency. Additionally, the popularization of the miniskirt was seen as an act of “enforced deculturization.”

Sundress: Anna Espinoza Spring 2022 (polyester taffeta)

Artificial flower crown: Anna Espinoza Spring 2022

Gender-bending dress is defined here as wearing clothing and adornments not typically associated with one’s assigned sex at birth. Ambiguity surrounding the questions of which garments are “male” or “female” has allowed for a loose interpretation of laws prohibiting gender-bending dress, which have been and still are weaponized against the LGBTQ community.

The laws of Oman, the U.A.E., and Negeri Sembilan in Malaysia ban “impersonating,” “posing as,” and “disguising oneself” as a woman. Abu Dhabi police have been known to make arrests for gender-bending dress on the charge of “violating public morals.” Prison sentences range from one month to two years and fines range from $280 to more than $4,000. In the U.S., the cities of Charleston, El Paso, and New Orleans have retained “masquerade laws” historically used to police gender-bending dress, which has been categorized as “disguise.” The use of masquerade laws to regulate gender-bending dress is an affirmation of the depth of ontology—the belief that who we really are is concealed, rather than revealed, by what we wear.

Fur coat: Made in Hong Kong (Finnish blue fox fur shell, acetate lining)

Mink stole

California was the first state to ban the sale of new animal fur products with Assembly Bill 44, which implements a statewide prohibition on manufacturing, selling, offering, displaying, trading, donating, or otherwise distributing any fur product in the state and includes exemptions for second-hand fur and leather sales as well as fur sales for “traditional tribal, cultural, or spiritual purposes” by members of Native American tribes. The penalty for violating the ban is a $500 fine for the first violation and $1,000 for repeated violations, with each fur product representing a separate violation.

Fur bans are said to be key to eliminating animal cruelty, reducing waste, and improving public health conditions. Mink, foxes, sables, rabbits, and other animals are raised in adjacent wire mesh cages and cared for via automated systems, then killed with electrocution and euthanasia. When it comes to environmental concerns, no fur—real or fake—is quick to biodegrade, and the tanning process that natural furs go through is toxic. Finally, fur farms increase the risks of spillover and spillback, or the cross-species transmission of disease, which results in novel disease variants.

Mink stole

California was the first state to ban the sale of new animal fur products with Assembly Bill 44, which implements a statewide prohibition on manufacturing, selling, offering, displaying, trading, donating, or otherwise distributing any fur product in the state and includes exemptions for second-hand fur and leather sales as well as fur sales for “traditional tribal, cultural, or spiritual purposes” by members of Native American tribes. The penalty for violating the ban is a $500 fine for the first violation and $1,000 for repeated violations, with each fur product representing a separate violation.

Fur bans are said to be key to eliminating animal cruelty, reducing waste, and improving public health conditions. Mink, foxes, sables, rabbits, and other animals are raised in adjacent wire mesh cages and cared for via automated systems, then killed with electrocution and euthanasia. When it comes to environmental concerns, no fur—real or fake—is quick to biodegrade, and the tanning process that natural furs go through is toxic. Finally, fur farms increase the risks of spillover and spillback, or the cross-species transmission of disease, which results in novel disease variants.

Used clothing bale: (various fibers, plastic packaging)

Used clothing bale: (various fibers, plastic packaging)Less than 20% of clothing donated to charity is actually repurposed there, and another 12% is recycled. The remainder of the 94 million tons of textile waste created each year is almost all shipped to the global south for a last chance at sale before going to a landfill, where it emits greenhouse gasses, chemicals, and dyes. Top exporters of used clothing believe they are alleviating poverty, reducing textile waste, and creating jobs. But saturating any market with used clothing strangles the domestic fashion industry and has a massive environmental impact. Nigeria, Haiti, Colombia, Paraguay, Bolivia, Venezuela, Peru, Mexico, Indonesia, and Saudi Arabia prohibit imports of used clothing.

Trade agreements offer preferential treatment on exports to the U.S.—namely, reduced tariffs and fewer quantity restrictions and the option to create free-trade zones on exports for countries who lower the barriers to U.S. exports of used clothing. In 2016, member states in the East African Community (EAC) indicated they would phase out used clothing imports. In response, the U.S. threatened to withdraw members of the EAC from the African Growth and Opportunity Act, a program supposedly designed to aid economic and political development, which would offer duty-free access to U.S. markets. Rwanda alone moved forward with the ban, and its AGOA benefits were subsequently withdrawn.

Crocodile pattern handbag: NihaoJewelry (pleather shell, polyester lining)

Crocodile pattern handbag: NihaoJewelry (pleather shell, polyester lining)Purchasing and carrying a counterfeit product in France could result in imprisonment of up to three years, and prosecutors can levy fines of up to $300,000. Penalties increase if the activity is part of a larger counterfeiting operation.

Does the strength of the anti-counterfeiting law tell us more about France’s concern for citizens, or more about its concern for the value of its luxury fashion industry? Does buying a fake piece really mean one deserves a real criminal record? American sensibilities, shaped by life under a legal system that has no intellectual property laws specifically meant for fashion, leave us more open to the idea of counterfeits. They can be a way to express a reverence for a designer or lifestyle that isn’t socially or financially attainable. Some counterfeits can trick expert authenticators, and are even made of the same materials as the real thing. This presents a sort of paradox for the concept of authenticity.

Hoodie: Hypland (cotton)

Boxer shorts: Hanes (cotton and polyester)

Jeans: Arizona Jeans (cotton and elastane)

The hoodie is banned in Georgia, Minnesota, and North Carolina, where it is forbidden to wear a mask, hood, or device by which any portion of the face is so hidden or covered as to conceal the identity of the wearer upon any public way or public property. “Sagging,” the practice of wearing one’s pants below the hips, revealing the underwear, is banned in Lynwood, Illinois, Union Point, Georgia, and Abbeyville, Louisiana.

These laws disproportionately affect young Black men and serve as justifications for stop-and-frisk policies. A Shreveport, Louisiana sagging ban led to the death of Anthony Childs, and the argument that a hoodie is threatening was invoked in the trial of George Zimmerman, Trayvon Martin’s killer. As Richard Ford Thompson writes, the result of this is that sagging and the hoodie have become “a statement of racial pride and defiance, solidarity with a community and an emblem of belonging”—and yet they are still policed.

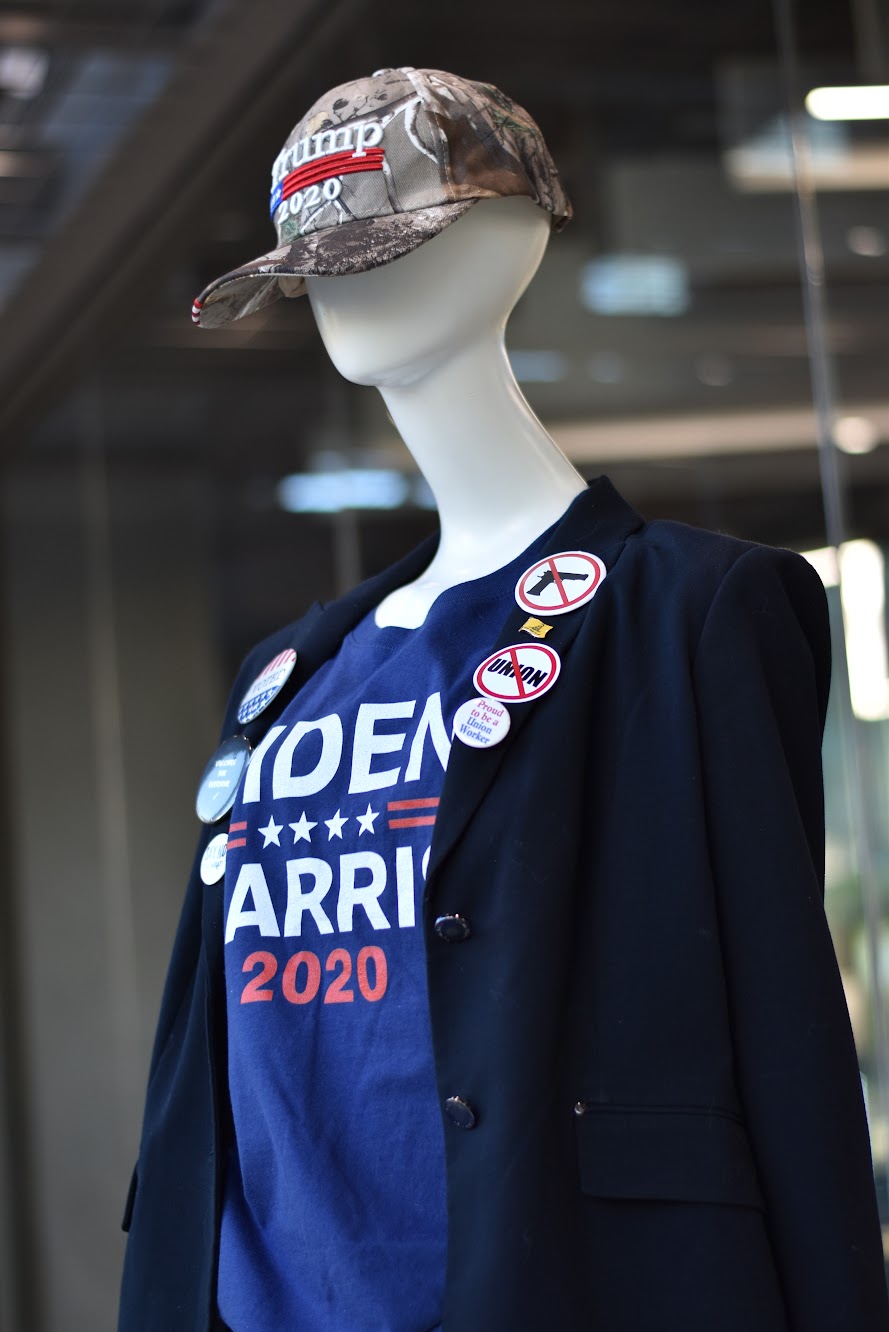

Baseball cap: Bestify Products (cotton and polyester)

Baseball cap: Bestify Products (cotton and polyester)T-shirt: Port and Company (100% cotton)

Assorted pins and stickers: Cafepress, Flagline, Presidential Election Historical Center, Redbubble

Blazer: Calvin Klein (polyester, rayon, spandex)

Pants: Talbots (rayon, cotton, spandex)

Some U.S. states and municipalities ban electioneering gear at the polls. Georgia bans “campaign gear,” while California and Texas prohibit the “badge, insignia, emblem, or other similar communicative device relating to a candidate, measure, or political party appearing on the ballot, or to the conduct of an election.” The states maintain that the purpose of the laws is to provide a peaceful and intimidation-free environment for voters.

A more vague ban on “political clothing” is being revised by the Minnesota State Legislature after it was struck down in 2010 by the U.S. Supreme Court.

T-shirt: Gildan (100% cotton, made in Bangladesh)

T-shirt: Gildan (100% cotton, made in Bangladesh)In Malaysia, the “Bersih 4” logo printed on a yellow shirt is banned. The logo is the emblem of a coalition of citizens fighting for what they call the “Clean 4”—clean elections, clean government, the right to dissent, and a better economy.

In 2015, 100,000 people took to the streets to protest the 1Malaysia Development Berhad embezzlement scandal, tens of thousands wearing the shirt. Malaysia's Security Minister used the Printing Presses and Publication Act to ban printed Bersih 4 materials, including the t-shirts, arguing they were “prejudicial to the public order…security…and national interest” and a “national security threat.” Shirt wearers were exposed to criminal liability.

The Shah Alam High Court sided with the Security Minister in a lawsuit brought by the Bersih 4 rally organizers.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics