Doris Domoszlai-Lantner is a fashion historian and archivist, and a Professor of Fashion Studies at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She has published her work in academic journals such as Vestoj, the International Journal of Fashion Studies, and several pieces in Fashion Studies Journal, as well as commercial outlets such as Splice Today, Fast Company, and Glamour. Her study “Fashioning a Soviet Narrative: Jean Paul Gaultier’s Russian Constructivist Collection” was published in the book Engaging with Fashion: Perspectives on Communication, Education and Business (Brill Publishers, 2018). Her co-authored study in Vestoj, “Tamas Kiraly: Hungary’s King of Fashion,” is the only English-language history study available on the avant-garde Hungarian designer Tamas Kiraly. Doris is an editor of the forthcoming book, Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice, Implications (Bloomsbury, July 2024). You can learn more about Doris on her website, Instagram, and LinkedIn page.

Petra Egri, PhD, is a fashion theorist, head of the Department of Applied Arts at the University of Pécs. Her awarded book on radical fashion performance was published in 2023 in

Hungarian (Fashion Theory, Theatricality, Deconstruction: Contemporary Fashion

Performances). Egri has published her research in professional fashion journals (Vestoj, BIAS) and served as a co-editor of three books about theatrical performances. Her paper, of late socialist neo-avantgarde fashion performances, was published in Russian Fashion Theory in 2019. She has a book chapter (Balmain x Barbie: A Fashion NFT Case Study) published by Bloomsbury in the book Digital Fashion: Theory, Practice and Implications. In 2022, her co-curated fashion exhibition (SOCIAL_EAST) was presented in New York City.

Cartoonist Matt Groening’s 34-year strong television show, The Simpsons, is known to take inspiration from real world people and places. Homer and Marge are named after Groening’s parents, Homer and Margaret; the Simpsons fa

Malibu Stacy, a problematic lady

In this, the 95th episode of The Simpsons, “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” (season 5, episode 14), Lisa, the passionate feminist, environmentalist, second-grade daughter of Marge and Homer, can’t wait to get her hands on the new, highly coveted, talking Malibu Stacy doll, a stand-in for Barbie in the fictional universe of the show. Malibu Stacy’s shapely, hourglass body with its prominent bosom is clad in a dress that was highly fashionable in the early ‘90s: a pink knee-length dress with a layered peplum waist. Stacy’s feet are sharply arched in high heels, a notably strong phallic marker in Sigmund Freud's study of the fetish, and a favorite object of fetishists to this day. “Long before fashion emphasized high heels, fetishists did, and they have consistently advocated heels significantly higher than the fashionable norm,” notes preeminent fashion historian Valerie Steele. [1]

![]() Malibu Stacy. Screenshot from The Simpsons.

Malibu Stacy. Screenshot from The Simpsons.

As she roleplays with Stacy giving a speech at the United Nations, Lisa’s hope quickly turns to anger when the pink-dress-clad Stacy begins to talk, spouting phrases like, “let’s bake some cookies for the boys,” and “don’t ask me, I’m just a girl.” The episode’s writers, Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein [2] modeled this version of Malibu Stacy off of Teen Talk Barbie, which debuted in 1992. Mattel created a library of 270 phrases, and programmed each individual doll to randomly speak four of them; while the majority of the doll’s phrases were unremarkable, a small percentage (1.5% of the 350,000 produced), spoke phrases like “math class is tough,” which provoked the disdain and anger of consumers, educators, and activists alike. [3] The president of the American Association of University Women (AAUW), Sharon Schuster, deftly noted the far-reaching implications of such a phrase, stating that “preteen girls most likely to play with Teen Talk Barbie are at the highest risk for losing confidence in their math ability.” [4]

Malibu Stacy, a problematic lady

In this, the 95th episode of The Simpsons, “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy” (season 5, episode 14), Lisa, the passionate feminist, environmentalist, second-grade daughter of Marge and Homer, can’t wait to get her hands on the new, highly coveted, talking Malibu Stacy doll, a stand-in for Barbie in the fictional universe of the show. Malibu Stacy’s shapely, hourglass body with its prominent bosom is clad in a dress that was highly fashionable in the early ‘90s: a pink knee-length dress with a layered peplum waist. Stacy’s feet are sharply arched in high heels, a notably strong phallic marker in Sigmund Freud's study of the fetish, and a favorite object of fetishists to this day. “Long before fashion emphasized high heels, fetishists did, and they have consistently advocated heels significantly higher than the fashionable norm,” notes preeminent fashion historian Valerie Steele. [1]

Malibu Stacy. Screenshot from The Simpsons.

Malibu Stacy. Screenshot from The Simpsons.As she roleplays with Stacy giving a speech at the United Nations, Lisa’s hope quickly turns to anger when the pink-dress-clad Stacy begins to talk, spouting phrases like, “let’s bake some cookies for the boys,” and “don’t ask me, I’m just a girl.” The episode’s writers, Bill Oakley and Josh Weinstein [2] modeled this version of Malibu Stacy off of Teen Talk Barbie, which debuted in 1992. Mattel created a library of 270 phrases, and programmed each individual doll to randomly speak four of them; while the majority of the doll’s phrases were unremarkable, a small percentage (1.5% of the 350,000 produced), spoke phrases like “math class is tough,” which provoked the disdain and anger of consumers, educators, and activists alike. [3] The president of the American Association of University Women (AAUW), Sharon Schuster, deftly noted the far-reaching implications of such a phrase, stating that “preteen girls most likely to play with Teen Talk Barbie are at the highest risk for losing confidence in their math ability.” [4]

Teen Talk Barbie. Courtesy of Mattel.

Teen Talk Barbie. Courtesy of Mattel.“We are pleased that Barbie has finally been given a voice. But it’s a shame that Mattel didn’t give her a more confident one.”

By engaging in self-deprecating, patriarchy-serving behavior, the cartoon Malibu Stacy satirizes the physical Teen Talk Barbie, whose questionable phrases reinforced gendered stereotypes for the real consumers who played with them. In The Simpsons episode, however, all of Malibu Stacy’s phrases are problematic. Moreover, Malibu Stacy’s body and the phrases she speaks combine to reinforce the stereotype that women should not only do things that make them good girlfriends or housewives, but also be what gender studies scholar Judith Butler explains is the embodiment of male fantasies [5], with females being phallogocentrically represented [6] as a subordinate to the primary, masculine, center of power. For one, Malibu Stacy suggests that it is not enough to serve men—“let’s bake some cookies for the boys,” she says—but that a young woman must also conform to stereotypical representational schemes of the erotic female body embodied in male fantasies. Fashion theorist Barbara Vinken described this fantastical expectation as: “women are supposed to embody a norm that is simultaneously an ideal form, the schema of an ideal, standard-setting body. Fashion exhibits artificiality and inaccessibility precisely in this strived-for goal of embodying the ideal.” [7]

In addition, Malibu Stacy's speech also undercuts the push for women's participation in society, with phrases like "don't ask me, I’m just a girl." The word "just" is of paramount significance, as it undermines a modernist notion that the two sexes have an equal chance of starting a public discourse, giving credence to Butler’s and Derrida’s theory that the masculine is privileged. The “just” confirms the exclusive role given to the girl/woman as a secondary subject: beautiful and with nothing to add to a conversation. Effectively, Malibu Stacy suggests a binary opposition: while a woman is “just a girl,” a man is not “just a boy,” echoing Vinken’s argument that “the inauthenticity of women is the necessary condition of the authenticity of men.” [8]

In addition, Malibu Stacy's speech also undercuts the push for women's participation in society, with phrases like "don't ask me, I’m just a girl." The word "just" is of paramount significance, as it undermines a modernist notion that the two sexes have an equal chance of starting a public discourse, giving credence to Butler’s and Derrida’s theory that the masculine is privileged. The “just” confirms the exclusive role given to the girl/woman as a secondary subject: beautiful and with nothing to add to a conversation. Effectively, Malibu Stacy suggests a binary opposition: while a woman is “just a girl,” a man is not “just a boy,” echoing Vinken’s argument that “the inauthenticity of women is the necessary condition of the authenticity of men.” [8]

Screenshot from “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy,” The Simpsons.

Screenshot from “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy,” The Simpsons.Lisa Lionheart, what kind of feminist are you?

In 1985, Elizabeth Wilson connected the then-burgeoning field of fashion studies to feminist discourse in her pivotal book Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. In exploring the concept of ambivalence, Wilson admonishes scholars who have, in their attempts to reconcile feminist theory and fashion, created an “unresolved syllogism” and an “inappropriate feminist ambivalence” [9] that disregards fashion’s complex multitudes. Wilson also notes, however, that there is an ‘appropriate ambivalence’ created by the relationship between modernism and fashion that is of contradictory and irreconcilable desires, inscribed in the human psyche by that very ‘social construction’ that decrees such a long period of cultural development for the human ego. Fashion—performance art—acts as a vehicle for this ambivalence, the daring of fashion speaks dread as well as desire. [10]

According to Wilson, fashion is inherently contradictory; we are “drawn to it, yet repelled by a fear of what we might find hidden within.” [11] The same is true of Lisa: she longs for Stacy, with her flowy blonde hair and chic pink dress, but is disappointed by her voice and what she stands for. Although she is young, Lisa understands the act of Othering suggested by Derrida and Butler, and she finds her doll’s vocalizations to be outrageous. In 1992, AAUW President Schuster lamented in 1992 that “we are pleased that Barbie has finally been given a voice. But it's a shame that Mattel didn't give a more confident one.” [12] In an attempt to salvage the situation and her love for the doll, Lisa similarly laments: “come on, Stacy…I’ve waited my whole life to hear you speak. Don’t you have anything relevant to say?” Lisa’s despair is akin to what philosopher and psychoanalyst Julia Kristeva describes in her seminal essay, “Women’s Time,” when she notes that women “seem to feel that they are the casualties, that they have been left out of the socio-symbolic contract, of language as the fundamental social bond. They find no affect there, no more than they find the fluid and infinitesimal significations of their relationships with the nature of their bodies, that of the child, another woman or a man.”[13]

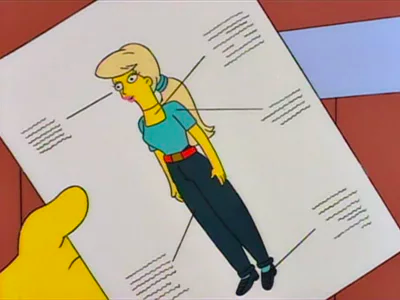

Kristeva ruminates about women facing the prospect of an “impossible identification,” in society, which leads to the Lacanian rejection of the Symbolic—the rejection of the paternal function. Lisa Simpson, who is unable to identify with Malibu Stacy, faces this kind of impossible identification. Malibu Stacy’s spouting of yet another awful phrase awakens an intense anger and desire to remedy not only the doll but the conditions which lead her to be created. Lisa channels those feelings to seek out Stacy Lovell, the creator and namesake of Malibu Stacy, whom she convinces to make a new talking doll that will instead share feminist thoughts and advice with her consumers. The doll, Lisa Lionheart, dutifully named after Lisa herself, is the visual and audial opposite of Malibu Stacy. She is quaintly dressed in a turquoise-colored shirt with a high neckline, with casual, cuffed jeans with a red belt, and socks poking through her flat, closed shoes, wearing her hair in a neatly combed, low ponytail. Unlike Malibu Stacy, she speaks what Lisa considers to be feminist phrases such as “if I choose to get married I’m keeping my own name,” and “trust in yourself and you can achieve anything!”

Plans for Lisa Lionheart doll. Screenshot from “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy,” The Simpsons.

“Malibu Stacy suggests a binary opposition: while a woman is ‘just a girl,’ a man is not ‘just a boy.’”

In “Women's Time,” Kristeva offers a deconstructive approach to understanding gender and gender differences, identifying three major phases—or waves, as it is most often referred—in the feminist struggle throughout history:

Kristeva aptly observes that the first phase of feminism, in which women strive for an equal footing in sociopolitical considerations (e.g., equal pay, voting rights, etc), “globalize[d] the problems of women of different milieux, ages, civilizations or simply of varying psychic structures, under the label ‘Universal Woman.’” [15] The second phase embraced varying identities and interpretations of femininity, and were “essentially interested in the specificity of female psychology and its symbolic realizations, these women seek to give a language to the intra- subjective and corporeal experiences left mute by culture in the past.” [16] The third phase, which Kristeva said was in the process of being formed at the time of her writing (1981), women move past the binary masculine and feminine identities, “arising, under the cover of a relative indifference toward the militance of the first and second generations, an attitude of retreat from sexism (male as well as female) and, gradually, from any kind of anthropomorphism.” [17]

Lisa, and by extension Lisa Lionheart, seems to belong to the third phase that Kristeva postulates is “a third generation, [which] does not exclude—quite to the contrary—the parallel existence three in the same historical time, or even that they be interwoven with the other.” [18] Like the first phase feminists, Lisa advocates for equal rights and representation in episode after episode. In "Mr. Lisa Goes to Washington” (Season 3, episode 2), Lisa wins a writing competition with her essay “The Roots of Democracy,” earning her a trip to the capitol, during which she becomes briefly disillusioned with the American government when she sees a male politician taking a bribe next to the Winifred Beecher Howe memorial. [19] However, she regains her admiration when the politician is removed from office. In other seasons, we see Lisa running for political office, and even becoming president herself ("Bart to the Future" [season 11, episode 17]), yet like second phase feminists, she stays true to her personal sartorial notions of femininity by wearing femme-presenting clothing. As a child she’s always in her orange dress and white pearl necklace, and as president, she wears that same necklace but with a purple pant suit, which some diehard Simpsons fans claim predicted the future purple outfit and pearl necklace that Vice President Kamala Harris wore to her inauguration in January over twenty years later. [20]

- when women claim an equal place in the symbolic order

- when women reject the male symbolic order on the grounds of their difference and exalt femininity

- when women reject the metaphysical juxtaposition of masculine and feminine [14]

Kristeva aptly observes that the first phase of feminism, in which women strive for an equal footing in sociopolitical considerations (e.g., equal pay, voting rights, etc), “globalize[d] the problems of women of different milieux, ages, civilizations or simply of varying psychic structures, under the label ‘Universal Woman.’” [15] The second phase embraced varying identities and interpretations of femininity, and were “essentially interested in the specificity of female psychology and its symbolic realizations, these women seek to give a language to the intra- subjective and corporeal experiences left mute by culture in the past.” [16] The third phase, which Kristeva said was in the process of being formed at the time of her writing (1981), women move past the binary masculine and feminine identities, “arising, under the cover of a relative indifference toward the militance of the first and second generations, an attitude of retreat from sexism (male as well as female) and, gradually, from any kind of anthropomorphism.” [17]

Lisa, and by extension Lisa Lionheart, seems to belong to the third phase that Kristeva postulates is “a third generation, [which] does not exclude—quite to the contrary—the parallel existence three in the same historical time, or even that they be interwoven with the other.” [18] Like the first phase feminists, Lisa advocates for equal rights and representation in episode after episode. In "Mr. Lisa Goes to Washington” (Season 3, episode 2), Lisa wins a writing competition with her essay “The Roots of Democracy,” earning her a trip to the capitol, during which she becomes briefly disillusioned with the American government when she sees a male politician taking a bribe next to the Winifred Beecher Howe memorial. [19] However, she regains her admiration when the politician is removed from office. In other seasons, we see Lisa running for political office, and even becoming president herself ("Bart to the Future" [season 11, episode 17]), yet like second phase feminists, she stays true to her personal sartorial notions of femininity by wearing femme-presenting clothing. As a child she’s always in her orange dress and white pearl necklace, and as president, she wears that same necklace but with a purple pant suit, which some diehard Simpsons fans claim predicted the future purple outfit and pearl necklace that Vice President Kamala Harris wore to her inauguration in January over twenty years later. [20]

Teen Barbies, talking. Photo by Brian Centrone.

Teen Barbies, talking. Photo by Brian Centrone.Lisa’s visual, sartorial, and audial overhaul of the idealized fashion doll takes her from an impossible identification to a possible one; she creates a doll with which she and other little girls can identify, admire and even imitate. Although the change in audio profile from Malibu Stacy’s to Lisa Lionheart’s was drastic, it was less radical than the actions of an anonymous group of performance artists called the Barbie Liberation Organization (BLO). In 1993, the BLO switched out the voiceboxes of hundreds of Teen Talk Barbies with those of G.I. Joe in an act of culture jamming that resulted in stereotypically “masculine” soundbites in the otherwise “girly” doll, and vice versa. The New York Times amusingly noted that “the result is a mutant colony of Barbies-on-steroids who roar things like ‘Attack!’ ‘Vengeance is mine!’ and ‘Eat lead, Cobra!’ The emasculated G. I. Joe's, meanwhile, twitter, ‘Will we ever have enough clothes?’ and ‘Let's plan our dream wedding!’” [21] The BLO’s action is briefly highlighted in The Simpsons when Lisa asks her schoolmates if they notice what is wrong with Malibu Stacy, and most of the girls initially fail to see the overarching problem, while only one of them notes that her doll, à la Spiderman, asks her: “my spidey-sense is tingling - anyone call for a web slinger?” According to Vinken, this is a pure act of fashion: “fashion is, at the risk of overstating the case, masquerade: transvestism, travesty,” [22] in which the travesty of the feminine is that it is masquerading as the masculine.

Teen Talk Barbie and G.I. Joe in the National Museum of American History:

Teen Talk Barbie and G.I. Joe in the National Museum of American History:https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1161262

In the end, fashion triumphs

After a television news report by the local anchorman Kent Brockman, Lisa eagerly awaits the impact of her advocacy as Lisa Lionheart hits the shelves of the toy store. However, after a campaign by the makers of Malibu Stacy to deflect attention from the new competitor takes shape, a “new edition” of Stacy is rolled out right in front of the group of girls clamoring to buy Lisa Lionheart. The new Malibu Stacy looks almost identical to the older model, with the exception of a wide-brimmed sun hat, which is apparently enough for the girls to choose her—effectively, the sexist, masculine-privileged values—over Lisa Lionheart, who symbolized a subversion of the oppositional binary.

Notes: Don’t Ask Me, I’m Just a Girl

[1] Valerie Steele, Fetish: Fashion, Sex and Power, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 99.

[2] “Lisa vs. Malibu Stacy,” IMDB, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0701159/.

[3] Sidney J. Kolpas, “Mathematical Treasure: Teen Talk Barbie,” Mathematical Association of America, June 2022, https://maa.org/press/periodicals/convergence/mathematical-treasure-teen-talk-barbie.

[4] Bob Greene, “Barbie! Say It Isn’t So,” Chicago Tribune, October 13th, 1992. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1992-10-18-9204040328-story.html.

[5] Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, (New York-London: Routledge, 1999), 39.

[6] Butler makes use of the term ‘phallogocentrism,’ which philosopher Jacques Derrida coined by combining the concepts of logocentrism and phallocentrism, in order to refer to the act of privileging the phallus (the masculine) as a symbol and source of power. Butler, Gender Trouble, 39.

[7] Barbara Vinken, “Transvesty–Travesty: Fashion and Gender,” Fashion Theory, vol. 3, iss. 1, (pp.33-50), Berg, 1999, 39.

[8] Barbara Vinken, “Transvesty–Travesty,” 39.

[9] Elizabeth Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, (New York: Virago Press, 1988), 245-6.

[10] Wilson, Adorned in Dreams, 246.

[11] Wilson, Adorned in Dreams, 247.

[12] “Company News: Critics Question Barbie’s Self-Esteem (Or Lack Thereof),” New York Times, October 2, 1992, https://www.nytimes.com/1992/10/02/business/company-news-critics-question-barbie-s-self-esteem-or-lack-thereof.html.

[13] Julia Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” translated by Alice Jardine and Harry Blake, Signs, Vol. 7, No. 1, Autumn, 1981, (pp. 13-35), The University of Chicago Press, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173503, 24.

[14] Kristeva, “Women’s Time.”

[15] Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” 19.

[16] Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” 19.

[17] Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” 34.

[18] Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” 34.

[19] While in D.C., Lisa tells Homer and Marge about the feminist “crusader” Winifred Beecher Howe, who lead the “Floormop Rebellion of 1910” and later appeared on the “highly unpopular seventy-five cent piece.” While this historical figure is made up, the character and her statue give us insight into the kind of role models Lisa has. “Winifred Beecher Howe Memorial,” Simpsons Wiki, https://simpsons.fandom.com/wiki/Winifred_Beecher_Howe_Memorial.

[20] Adam White, “Simpsons fans believe Lisa’s presidential outfit ‘predicted’ Kamala Harris’s inauguration ensemble,” Independent, January 21, 2021, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/tv/news/simpsons-predictions-kamala-harris-b1790490.html.

[21] David Firestone, “While Barbie Talks Tough, G. I. Joe Goes Shopping,” New York Times, December 31, 1993, sec. A, p. 12, https://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/31/us/while-barbie-talks-tough-g-i-joe-goes-shopping.html.

[22] Vinken, “Transvesty–Travesty: Fashion and Gender,” 34.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics