First Promotional shoot credit (@watermarkbyshuja)

First Promotional shoot credit (@watermarkbyshuja)Muhammad Umer Rehman considers himself a maker, dedicating his career to teaching while recognizing the need for discourse surrounding fashion in the Subcontinent. His research focuses on innovation in design through zero waste and sustainability, alongside a commitment to preserving traditional practices. His work intersects fashion history and materiality, aiming to connect historical crafts with contemporary needs.

Fast fashion has drastically changed how clothing is produced and consumed. Driven by consumer demand and globalization, garments are now produced in shorter cycles, often at the cost of labor rights and environmental health. The consequences include massive amounts of waste, unethical labor practices, and a disconnect between consumers and the making of clothing. Sustainable fashion seeks to reverse these trends by focusing on ethics, longevity, and environmental stewardship.

In Pakistan, a country with a deep-rooted history of textile and handloom traditions, fast fashion poses a threat to indigenous crafts. Simultaneously, these crafts present a significant opportunity to advance slower, more meaningful modes of fashion production, positioning them as alternatives to dominant industrial systems. U&I by Umerimrana is one such initiative that integrates traditional weaving, ethical sourcing, and contemporary design into a slow fashion model. This paper presents U&I as a case study to illustrate how such an approach can serve as a bridge between cultural heritage and sustainable innovation.

The fashion and textiles industry is widely regarded as one of the most unsustainable sectors today. Numerous scholars and institutions have outlined the environmental and cultural repercussions of fast fashion. The industry generates severe environmental impacts throughout the product lifecycle and is frequently associated with labor exploitation across global supply chains. [1] Simultaneously, the prevalence of fast fashion, defined by high-volume, low-cost, and standardized garments, fosters unsustainable consumption. Because these items lack lasting emotional or symbolic value, they are quickly discarded, generating higher levels of waste. [2]

Dasra’s report stresses the overwhelming impact that the rise of mass-produced clothing has had on traditional craft sectors. It notes that the widespread availability of cheap, factory-made garments has severely undermined the livelihoods of millions of artisans, pointing out that the mass consumption of inexpensive, trend-driven garments has significantly diminished the perceived value of handcrafted items. As fast fashion prioritizes constant novelty and low production costs, the cultural and material worth of artisanal work is increasingly overlooked. [3]

This shift in consumer perception has not only eroded appreciation for the time, skill, and heritage embedded in handcrafted goods, but has also jeopardized the survival of small-scale craftspeople whose livelihoods depend on sustained demand for their unique, labor-intensive creations. These artisans find themselves increasingly marginalized in a global economy that prioritizes speed, volume, and low cost over craftsmanship and sustainability. As the demand for fast fashion continues to rise, the space for handmade, regionally distinctive textile work continues to shrink, threatening not only economic survival but also the preservation of intangible cultural heritage.

Slow fashion, as defined by Štefko and Steffek, is not merely a response to the environmental and ethical crises posed by fast fashion—it is a holistic design and manufacturing philosophy that prioritizes sustainability, ethical labor practices, and the use of durable, high-quality materials. [4]

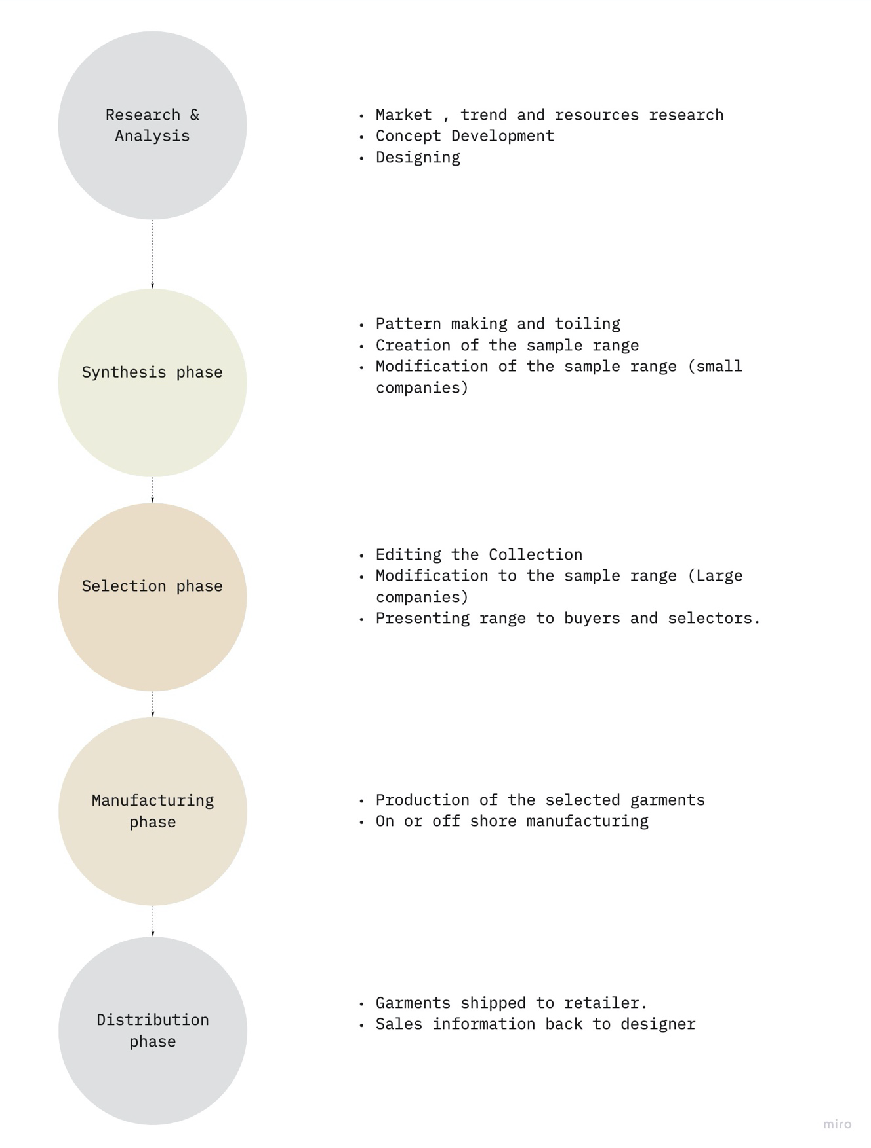

Rather than chasing seasonal trends or mass-market appeal, slow fashion encourages thoughtful consumption, transparency in the supply chain, and a deep respect for the people and processes behind each garment. It advocates for a shift from quantity to quality, where clothing is made to last and valued as an investment rather than a disposable commodity. For a more holistic approach towards quality over quantity, Gwilt introduces a five-phase model of sustainable fashion design that challenges the conventional segmentation of the fashion development process, advocating instead for a more integrated approach. [5] Adding to Gwilt’s proposal of a sustainable model, Rissanen examines the traditional model and suggests a disconnect between design and production as a key issue contributing to material waste and inefficiency. Their work highlights the need for closer collaboration across all stages of fashion creation. [6]

According to McQuillan, in traditional garment construction, approximately 15% of fabric is typically discarded during the cutting process. [7] This loss, often overlooked in mainstream fashion production, underscores the inefficiencies built into conventional design methods and points to the need for more sustainable, waste-reducing approaches such as zero-waste pattern cutting. Sinha adds that smaller fashion enterprises have the potential to foster more holistic engagement from designers, enabling them to participate in multiple stages of the production process. [8] Taking that into account, expanded involvement positions designers as pivotal agents of change, capable of embedding sustainability and ethical considerations into the very foundation of fashion practices.

These frameworks shape the analysis of U&I’s work and its challenge to conventional norms. The five-phase model of sustainable fashion design shows the traditional, segmented method of design and production, which often results in inefficiencies and material waste—highlighting the limitations of conventional fashion design—and advocates for a more sustainable, integrated approach. U&I counters this by adopting more sustainable strategies, such as minimum-waste pattern cutting, and by embedding the designer throughout the entire process from initial concept to the final stages of production. This approach, as advocated by Sinha, Štefko and Steffek, and Rissanen, is promoted as a more sustainable alternative to conventional fashion systems, emphasizing holistic design involvement, ethical practices, and waste reduction throughout the entire production process.

This study uses a qualitative case study methodology, focusing on U&I by Umerimrana. Data were collected through interviews with the founder-designer, process documentation, and observation of production practices. The research is contextualized through theoretical models of sustainable fashion and critiques of conventional design structures. Gwilt’s five-phase design model offers key insight into analyzing how U&I deviates from a traditional production process to consciously keep the designer involved from the first step till the last phase of production. [9]

Initiative Overview

U&I by Umerimrana operates as a small but impactful effective fashion initiative that promotes sustainability through collaboration with weavers, the use of surplus materials, and waste-conscious garment design. Rather than labeling itself as a completely sustainable brand, U&I identifies as a work-in-progress that strives towards minimal waste and ethical production. The initiative primarily focuses on women’s clothing, utilizing a process rooted in material constraints and creative adaptability.

In Pakistan, a country with a deep-rooted history of textile and handloom traditions, fast fashion poses a threat to indigenous crafts. Simultaneously, these crafts present a significant opportunity to advance slower, more meaningful modes of fashion production, positioning them as alternatives to dominant industrial systems. U&I by Umerimrana is one such initiative that integrates traditional weaving, ethical sourcing, and contemporary design into a slow fashion model. This paper presents U&I as a case study to illustrate how such an approach can serve as a bridge between cultural heritage and sustainable innovation.

Literature Review

The fashion and textiles industry is widely regarded as one of the most unsustainable sectors today. Numerous scholars and institutions have outlined the environmental and cultural repercussions of fast fashion. The industry generates severe environmental impacts throughout the product lifecycle and is frequently associated with labor exploitation across global supply chains. [1] Simultaneously, the prevalence of fast fashion, defined by high-volume, low-cost, and standardized garments, fosters unsustainable consumption. Because these items lack lasting emotional or symbolic value, they are quickly discarded, generating higher levels of waste. [2]

Dasra’s report stresses the overwhelming impact that the rise of mass-produced clothing has had on traditional craft sectors. It notes that the widespread availability of cheap, factory-made garments has severely undermined the livelihoods of millions of artisans, pointing out that the mass consumption of inexpensive, trend-driven garments has significantly diminished the perceived value of handcrafted items. As fast fashion prioritizes constant novelty and low production costs, the cultural and material worth of artisanal work is increasingly overlooked. [3]

This shift in consumer perception has not only eroded appreciation for the time, skill, and heritage embedded in handcrafted goods, but has also jeopardized the survival of small-scale craftspeople whose livelihoods depend on sustained demand for their unique, labor-intensive creations. These artisans find themselves increasingly marginalized in a global economy that prioritizes speed, volume, and low cost over craftsmanship and sustainability. As the demand for fast fashion continues to rise, the space for handmade, regionally distinctive textile work continues to shrink, threatening not only economic survival but also the preservation of intangible cultural heritage.

Slow fashion, as defined by Štefko and Steffek, is not merely a response to the environmental and ethical crises posed by fast fashion—it is a holistic design and manufacturing philosophy that prioritizes sustainability, ethical labor practices, and the use of durable, high-quality materials. [4]

Rather than chasing seasonal trends or mass-market appeal, slow fashion encourages thoughtful consumption, transparency in the supply chain, and a deep respect for the people and processes behind each garment. It advocates for a shift from quantity to quality, where clothing is made to last and valued as an investment rather than a disposable commodity. For a more holistic approach towards quality over quantity, Gwilt introduces a five-phase model of sustainable fashion design that challenges the conventional segmentation of the fashion development process, advocating instead for a more integrated approach. [5] Adding to Gwilt’s proposal of a sustainable model, Rissanen examines the traditional model and suggests a disconnect between design and production as a key issue contributing to material waste and inefficiency. Their work highlights the need for closer collaboration across all stages of fashion creation. [6]

According to McQuillan, in traditional garment construction, approximately 15% of fabric is typically discarded during the cutting process. [7] This loss, often overlooked in mainstream fashion production, underscores the inefficiencies built into conventional design methods and points to the need for more sustainable, waste-reducing approaches such as zero-waste pattern cutting. Sinha adds that smaller fashion enterprises have the potential to foster more holistic engagement from designers, enabling them to participate in multiple stages of the production process. [8] Taking that into account, expanded involvement positions designers as pivotal agents of change, capable of embedding sustainability and ethical considerations into the very foundation of fashion practices.

These frameworks shape the analysis of U&I’s work and its challenge to conventional norms. The five-phase model of sustainable fashion design shows the traditional, segmented method of design and production, which often results in inefficiencies and material waste—highlighting the limitations of conventional fashion design—and advocates for a more sustainable, integrated approach. U&I counters this by adopting more sustainable strategies, such as minimum-waste pattern cutting, and by embedding the designer throughout the entire process from initial concept to the final stages of production. This approach, as advocated by Sinha, Štefko and Steffek, and Rissanen, is promoted as a more sustainable alternative to conventional fashion systems, emphasizing holistic design involvement, ethical practices, and waste reduction throughout the entire production process.

Methodology

This study uses a qualitative case study methodology, focusing on U&I by Umerimrana. Data were collected through interviews with the founder-designer, process documentation, and observation of production practices. The research is contextualized through theoretical models of sustainable fashion and critiques of conventional design structures. Gwilt’s five-phase design model offers key insight into analyzing how U&I deviates from a traditional production process to consciously keep the designer involved from the first step till the last phase of production. [9]

U&I by Umerimrana: A Case Study

Initiative Overview

U&I by Umerimrana operates as a small but impactful effective fashion initiative that promotes sustainability through collaboration with weavers, the use of surplus materials, and waste-conscious garment design. Rather than labeling itself as a completely sustainable brand, U&I identifies as a work-in-progress that strives towards minimal waste and ethical production. The initiative primarily focuses on women’s clothing, utilizing a process rooted in material constraints and creative adaptability.

Concept and mood board.

Concept and mood board.“Rather than chasing seasonal trends or mass-market appeal, slow fashion encourages thoughtful consumption, transparency in the supply chain, and a deep respect for the people and processes behind each garment.”

Integrated Design Process

U&I deviates from mainstream fashion practices by ensuring that the designer remains involved from the earliest stages of development through to the final execution. This continuous engagement contrasts with Gwilt’s five-phase model of sustainable fashion design, which suggests that designers are traditionally limited to the initial research and analysis phase, remaining largely disconnected from production. In U&I’s process, the first phase begins with the selection of yarn—often determined by the availability of surplus from the local textile industry—which in turn sets the parameters for design. This inverse design approach, grounded in material availability, not only fosters creative problem solving, but also minimizes the need for new resource consumption. Furthermore, the designer’s close collaboration with artisans helps to revive traditional skills that are increasingly endangered due to industrialization and mass production.

Supporting Gwilt’s model is Rissanen’s critique of the traditional fashion production system as inefficient and unsustainable. [10] U&I challenges this conventional model by embedding the designer in every phase of the process—from thread selection to garment finishing—ensuring continuous involvement and greater accountability in both creative and production decisions.

Five Phases of Design and Production (Gwilt, 2011:40).

Five Phases of Design and Production (Gwilt, 2011:40). Leftover yarn procured from the local textile industry

Leftover yarn procured from the local textile industrySourcing and Weaving

U&I’s reverse approach, grounded in material sourcing, reduces dependence on new resources and promotes creative design solutions. It repurposes surplus materials that would otherwise go to waste, while still maintaining high-quality standards particularly in terms of colorfastness and yarn durability. However, the unpredictable availability of surplus yarn colors and types challenges designers to adapt creatively. Rather than having the option of selecting yarns based on preferred thread count or color palette, designers must develop weaves based on what is accessible, often allowing material constraints to drive design innovation.

These creative limitations in textile design lead to the development of unique fabric patterns and foster innovation. For example, the image below illustrates the initial phase of the weaving process, where yarn spools are arranged on a spool rack according to the repeat size of the design. The threads used in this design range from a 60/1 (sixty single) to an 80/2 (eighty double) thread count. In the context of apparel fabric, a higher thread count results in finer fabric, while a lower thread count produces thicker fabric suitable for home and upholstery.

Understanding the thread count spectrum and its availability from the industry allows designers to arrange the threads in a manner that creates varied textures and contrasts within the fabric. This results in unique design qualities, where the thinness or thickness of the fabric varies within the same piece, adding visual and tactile interest.

Handloom weavers are also integral to the process. They work closely with the designer to produce fabrics in varied surface patterns such as stripes, checks, and jacquards. The fabrics are customized to fit garment specifications like breathability and drape, suited to Pakistan’s climate and consumer preferences.

However, handloom weaving presents a challenge when working with higher thread counts, such as 60/1 to 100/1 and above. During the weaving process, finer threads tend to break more easily, causing disruptions in the weaving process. To mitigate this issue, only threads with a count of 60/2 to 100/2 and above are typically used for the warp, while single-ply threads are reserved for the weft. This combination allows for smoother weaving with minimal thread breakage, ensuring the handloom operates efficiently and produces a consistent, high-quality fabric.

Top: Making of the warp credit (@watermarkbyshuja)

Top: Making of the warp credit (@watermarkbyshuja)Second: Knotting of new warp on jacquard loom credit (@watermarkbyshuja)

Middle: Jacquard loom History (Thames and Hudson) from a relative in France. Lynn, December 1996.

Second from bottom: Prototype and fabric selection process

Bottom: Prototype and fabric selection process

Garment Design and Waste Minimization

Buzzwords in today’s fashion industry—recycle, repurpose, reuse, zero waste—have long been embedded in the everyday practices of South Asian households. This culture of frugality and respect extends beyond clothing to cooking, carpentry, and all things handmade. The handmade is valued not only for its craftsmanship, but also for the time and care it represents. Omura Shige (1918-1999) was a distinguished essayist known for her deep appreciation of daily life and the cherished customs of Kyoto. She eloquently said, “Objects have life, so we must treasure them until their life is over. Her works reflect not only a profound connection to her heritage but also a compassionate perspective on the importance of preserving culture and simplicity in a rapidly modernizing world, something that resonates with the design philosophy and practice at U&I.

At U&I, garment inspiration is drawn from classic South Asian silhouettes, including the kurta, shalwar, and angarkha. These garments, rooted in centuries-old traditions, were, and in many cases still are, constructed using basic geometric shapes such as rectangles, squares, circles, and triangles. This method not only ensured simplicity and clarity in construction but also inherently minimized waste. Every cut-out or leftover piece had a purpose, often being reused to finish or embellish the garment. Remarkably, once the garment had served its intended purpose, it could be unstitched and reassembled, returning to its original yardage. This practice of reusing materials is a testament to circularity, predating modern sustainability efforts by centuries. As highlighted in Indian Costumes in the Collection of The Calico Museum of Textiles, the use of geometric patterns in South Asian garment construction has long emphasized both functionality and sustainability, with many garments designed to maximize fabric use and minimize waste. [11] Additionally, Sinha discusses how these traditional practices align with modern circular fashion principles, showcasing their inherent sustainability long before contemporary design frameworks were developed. [12] Instead of following transient fashion trends, the U&I design process listens to the fabric, the hands that weave it, and the environment from which it comes. There is an intentionality in every stitch—a dialogue between material, maker, and user.

U&I embraces a mindset of appreciation and intentionality by creating garments that are timeless in silhouette and comfortable in form. This approach not only ensures simplicity and clarity in making but also inherently minimizes waste.Their motivation stems from a deep sensibility toward traditional forms, reinterpreted through contemporary lenses and construction techniques to suit modern consumers. The process is grounded in smart design: cuts are planned to maximize fabric usage and minimize waste. Every garment considers width, shrinkage, and layout efficiency before any pattern is finalized. Prototypes and mock-ups are made to test construction feasibility, and off-cuts are repurposed as finishings, trims, or accessories—extending the life and value of every inch of fabric. As McQuillan notes, reducing cutting waste is critical to sustainable fashion practice. [13] U&I’s approach turns this principle into reality.

In doing so, they create not only garments but also systems of care, respect, and continuity, where clothing is more than style; it is stewardship.

In doing so, they create not only garments but also systems of care, respect, and continuity, where clothing is more than style; it is stewardship.

Analysis

U&I’s model challenges the linear, profit-driven fashion supply chain. Its integration of designer, weaver, and waste management reflects a holistic approach that is often missing in larger operations. The designer’s close collaboration with artisans revives skills that are in decline due to industrialization.

The brand also reclaims agency over fashion consumption by encouraging customers to consider the story and process behind each garment. In doing so, it fosters a deeper connection between wearer and maker—an essential pillar of the slow fashion philosophy.

Top: Ammad Hassan Ansari, 3rd generation weaver Credits @watermarkbyshuja

Top: Ammad Hassan Ansari, 3rd generation weaver Credits @watermarkbyshujaMiddle: Muhammad Saleem Ansari, master weaver Credits @watermarkbyshuja

Bottom: Fahad Hassan Ansari, 3rd Generation weaver Credits @watermarkbyshuja

Moreover, U&I demonstrates that sustainable fashion can emerge organically from existing systems. By redirecting surplus material and working within constraints, the brand reduces environmental impact while retaining cultural specificity. Its example presents a scalable yet localized model that other designers and entrepreneurs could replicate. Sinha emphasizes that small enterprises enable designers to have a more holistic view of the production process, allowing for a stronger integration of sustainable practices from design to manufacturing. [14] This approach, which blends traditional craftsmanship with circular design principles, enables U&I to minimize waste and extend the longevity of their products, aligning with sustainability practices that predate current mainstream efforts in the fashion industry. Active involvement in design and making supports human wellbeing, a philosophy that resonates with the design process at U&I and supports their mission. Said simply, in the words of Csikszentmihalyi, happiness arises from creation and discovery. [15] It is this creative practice of problem-solving and finding ways to achieve one's goal that leads toward sustainable thinking and makes all the hurdles worthwhile.

Top: First fashion showcase at Pantene Hum Showcase of the final garments. Credit: Humshowcase media

Top: First fashion showcase at Pantene Hum Showcase of the final garments. Credit: Humshowcase mediaBottom: First fashion showcase at Pantene Hum Showcase of the final garments. Credit: Humshowcase media

Conclusion

U&I by Umerimrana represents an effective model of slow fashion, deeply rooted in cultural heritage, sustainability, and community engagement. By emphasizing reuse, ethical collaboration, and conscious design, it offers a convincing alternative to the wastefulness of fast fashion. The initiative revitalizes traditional crafts within a contemporary context, demonstrating that sustainability does not require abandoning culture; it can, in fact, emerge from it.

This research highlights the critical role of designers in fostering a craft-centric, responsible fashion movement in Pakistan. As Sinha argues, deeper designer involvement across the supply chain is essential for creating ethical and sustainable systems, particularly in contexts where traditional craft knowledge is at risk. By advocating for waste reduction and accountability in the fashion industry, this work calls for a renewed appreciation of indigenous weaving traditions and echoes Dasra's findings on the need to support artisan livelihoods through sustainable development.

Furthermore, U&I’s design approach aligns with zero-waste methodologies outlined by McQuillan and Rissanen, which challenge conventional fashion paradigms and promote innovative pattern-cutting and material-use strategies. This integration of sustainability into the design process supports Gwilt’s assertion that responsible fashion must begin at the earliest stages of creation.

Ultimately, this case study emphasizes the need to rethink the fashion design process entirely, encouraging designers to reconnect not only with materials but also with the communities and cultural narratives behind them. Craft can serve as both an economic and ecological solution, bridging tradition and innovation in the service of a more sustainable future.

Notes: Sustainable by Design

[1] Eunsuk Hur and Katharine J. Beverley, “The Role of Craft in a Co-Design System for Sustainable Fashion,” in Making Futures: The Crafts as Change Maker in Sustainably Aware Cultures, Proceedings of the Conference, Dartington Hall, Devon, September 15–16, 2011 (Plymouth: Plymouth College of Art, 2013).

[2] Kate Fletcher, Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys (London: Earthscan, 2008), cited in Eunsuk Hur and Katharine J. Beverley, “The Role of Craft in a Co-Design System for Sustainable Fashion,” in Making Futures: The Crafts as Change Maker in Sustainably Aware Cultures, Proceedings of the Conference, Dartington Hall, Devon, September 15–16, 2011 (Plymouth: Plymouth College of Art, 2013).

[3] Dasra: catalyst for social change and The Edmond De Rothschild Foundations, “Crafting a Livelihood: Building Sustainability for Indian Artisans,” January 2013, accessed August 25, 2025, https://www.dasra.org/pdf/resources/Crafting a Livelihood - Building Sustainability for Indian Artisans.pdf.

[4] Róbert Štefko and Vladimira Steffek, “Key Issues in Slow Fashion: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives,” Sustainability 10, no. 7 (July 2, 2018), https://doi.org/10.3390/su10072270.

[5] Alison Gwilt, A Practical Guide to Sustainable Fashion (London: Fairchild Books, 2011).

[6] Timo Rissanen, “Waste and the Re-fashioning of Fashion,” in Sustainability and Social Change in Fashion, ed. Leslie Davis Burns and Jeanne Carver (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 199–215.

[7] Holly McQuillan, “Zero-Waste Design Practice: Strategies and Risk Taking for Apparel Design,” Fashion Practice 3, no. 1 (2011): 29–62.

[8] Pammi Sinha, “Creativity in Fashion,” Journal of Textile and Apparel, Technology and Management 2, no. 4 (2002): 1–16, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/237334691_Creativity_in_fashion.

[9] Gwilt, A Practical Guide to Sustainable Fashion.

[10] Timo Rissanen, “Fashion Design for Living,” in Sustainable Fashion: What’s Next? A Conversation about Issues, Practices, and Possibilities, ed. Janet Hethorn and Connie Ulasewicz, 2nd ed. (New York: Fairchild Books, 2015), 119–138.

[11] B.N. Goswamy and Kalyan Krishna, Indian Costumes in the Collection of the Calico Museum of Textiles (Ahmedabad, India: Calico Museum of Textiles, 2002).

[12] Sinha, “Creativity in Fashion.”

[13] McQuillan, “Zero-Waste Design Practice: Strategies and Risk Taking for Apparel Design.”

[14] Sinha, “Creativity in Fashion.”

[15] Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (New York: HarperCollins, 1996), cited in Eunsuk Hur and Katharine J. Beverley, “The Role of Craft in a Co-Design System for Sustainable Fashion,” in Making Futures: Craft and the (Re)Turn of the Maker in the Post Global Sustainable Future, ed. Malcolm Ferris (Plymouth: Plymouth College of Art, 2013).

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics