Cydni Meredith Robertson, Ph.D., is an Assistant Professor at Indiana University Bloomington in Bloomington, Indiana, in the Eskenazi School of Art, Architecture, and Design, Fashion Merchandising program. Her research interests include a) women’s experiences in the global apparel supply chain and b) the preservation of culture, dress, and identity practices.

Fashion Griotte and Sankofa Approach to Costume Design

Fashion griotte Ruth E. Carter can simultaneously call forth both the past and the future, with timeless synergy, through the art of costume design. Traditional griottes/griots in West African, Senegalese, Wolof tradition express and preserve oral histories through song, poetry, and storytelling, as purposefully passed down from their ancestors. [1, 2] Carter has committed herself to authentically telling African diasporic narratives by employing creative design in clothing and accessories as her preferred medium of legacy communication. While Carter is renowned as a two-time Academy Award winner for her work in the Black Panther film franchise, Black Panther (2018) and Wakanda Forever (2022), her costuming debut in the Spike Lee joint School Daze (1988) began over 37 years of her fashioning Africentric films. From her work in motion pictures such as Malcolm X (1992), Amistad (1997), B.A.P.S. (1997), Selma (2015), Lee Daniels’ The Butler (2013), and Sinners (2025), it is evident that Carter leans on and learns from the aesthetics of the past to meaningfully connect with fashion and film consumers in the present.

In this review of Carter’s costume-in-film anthology, we explore her work through a Sankofa lens that borrows from the Akan, Ghanaian term meaning it is not taboo to go back and fetch that which is at risk of being left behind, or it is not forbidden to go into history to validate and reclaim the past, or to look to the past to inform the future. [3, 4, 5]

The Adinkra symbol of the Sankofa bird illustrates the figure as flying forward yet looking backward, symbolizing the connection of the past and the present of the African diaspora with hopes for a brighter future. [6] Much like the Sankofa bird, Carter has contributed towards her hopes of a brighter, and Blacker, future in both fashion and film for nearly four decades. In honor of the 15th anniversary of the MA Fashion Studies program at Parsons School of Design, this reflection celebrates the past 15 years of Carter’s work with abiding gratitude and ancestral reverence.

Ruth E. Carter in Academic Literature

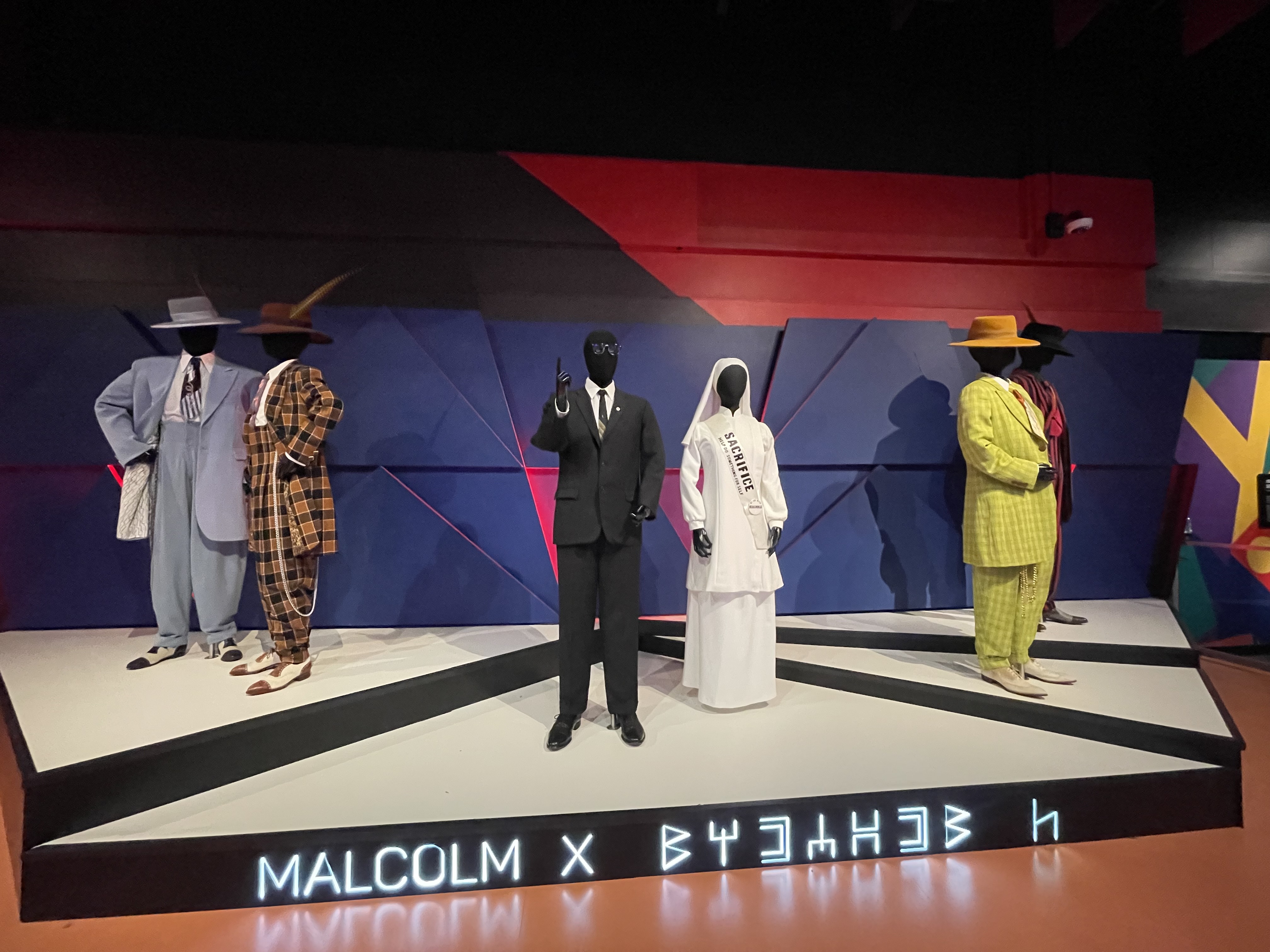

Recent fashion scholarship has examined Carter and her work by acknowledging the visual and narrative tools used to convey historical and political dress. In the film Malcolm X, Carter’s characters donned patterned, colorful, and intentionally oversized wool and silk Zoot suits which were deemed unpatriotic and culturally offensive in their time. These Zoot suits of the 1940s were also perceived negatively due to the excessive use of fabric required to construct the garments during wartime rationing and to general racialized aggression towards Mexican, Filipino, Italian, and Black American freedom of expression. [7, 8] Researchers have analyzed the complex significance of Black skin and heroic costuming from a postcolonial view as displayed in the Black Panther films. [9] Scholars have also admired the impact of historically accurate cultural dress on cinematic queens such as Wakanda’s Queen Ramonda and her array of Isicholo (see: Isicolo) South African Zulu married woman’s crowns, the majority of which were 3D-printed specifically for the film. [10] Carter’s work has also been cited in books that cater to both the academic and public audiences, including her own visual autobiography, museum exhibition reviews, doctoral dissertations, and an abundance of news articles. [11-15] The presence of Carter’s work within these vast yet connected outlets signifies the present-day relevance of her historic and futuristic art across timelines, disciplines, and audiences. To expand upon the historicism woven into Carter’s work, the following section illustrates how she intentionally places markers of time and space in the African diaspora into her costuming practices.

Top: Queen Mother Costume for the film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, designed by Ruth E. Carter. Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Top: Queen Mother Costume for the film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever, designed by Ruth E. Carter. Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum. Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025. Bottom: Costuming from the film Malcolm X, designed by Ruth E. Carter.

Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Afrohistoricism - Fashion in Film that Looks Backward

Within academic literature and mainstream media, the terms Afrocentrism and Africentrism have been widely adopted. [16, 17] However, the rarely applied portmanteau Afrohistoricism now has the opportunity to be defined through the perspective of visual art and preservation of African diasporic cultural dress and identity. [18] The thread consistently woven within Carter’s work is Afrohistoricism—positive, holistic, and forward-thinking visual messaging about Black life and culture. Since 2010, Carter has designed notable nostalgic films such as Sparkle (2012), set in the 1960s Motown Detroit era, Marshall (2017), set in progressive 1940s Connecticut, and Sinners (2025), set in post-World War I 1930s Mississippi.

In The Butler, Carter personifies disco culture and the Black-is-Beautiful movement of the 1970s, with characters Cecil (Forest Whittaker) and Gloria (Oprah Winfrey) sporting matching textured black-and-white jumpsuits, inspired by a 1973 Eleganza mail-order catalog in a Frederick’s of Hollywood advertisement. [19] This costuming holds the energy of cultural revolution and self-revelation, as expressed through fashion, music, dance, and loving partnership. [20]

Top: Ruth E. Carter’s webpage, Collection, The Butler

Top: Ruth E. Carter’s webpage, Collection, The ButlerBottom: Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum. Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Yet, Carter does not limit herself to clothe-it-all-joy. In the film Selma (2015), Carter designed five dresses made of silk, cotton, taffeta, organza, and silk velvet to dress the characters representing the four little girls who passed (Carol Denise McNair, Cynthia Dionne Wesley, Addie Mae Collins, and Carole Rosamond Robertson) and one survivor (Sarah Collins Rudolph) in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing on September 15, 1963. The tragic event ignited the poem “Birmingham Sunday” (September 15, 1963) by Langston Hughes, which quotes, “Four little girls, who went to Sunday School that day, and never came back home at all - but left instead, their blood upon the wall, with spattered flesh, and bloodied Sunday dresses…”. [21] The range in Carter’s art extends beyond costume design. Her work crosses realms that connect with the human experience, bringing past pain and future hope to life through dress. These future hopes are illustrated in the following section as Carter’s influence on Afrofuturism and the Black Fantastic shines in her more recent films.

Author’s Note: As I was taking in the heaviness and beauty of the five dresses in this image at the Indianapolis Children’s Museum, I heard the voice of a little girl walk by and say, “Ooh, pretty dresses!”. Those simple, yet powerful, words almost brought me to tears. While the little girl knew nothing of the significance behind these Sunday-best dresses, her innocence humanized the experience of Denise, Cynthia, Addie Mae, Carole, and Sarah. May all little girls be able to grow old and reflect on the ‘pretty dresses’ they once wore.

Top: Five little girls’ dresses for the film Selma, designed by Ruth E. Carter.

Photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.Bottom: Source - Medium, “Four Little Girls, 58 Years Later,” article by: Chloe Smith. Retrieved June 2025.

“The Adinkra symbol of the Sankofa bird illustrates the figure as flying forward yet looking backward, symbolizing the connection of the past and the present of the African diaspora with hopes for a brighter future.”

Afrofuturism and The Black Fantastic - Fashion in Film that Flies Forward

When the first Black Panther film was released into theaters, fans and scholars alike erupted with excitement and critique, guided by an Afrofuturistic framework. [22, 23] Authors such as Octavia Butler, lovingly positioned as “The Mother of Afrofuturism" in literature, have researched and applied Afrofuturistic themes in their renowned work for decades. [24, 25] An extension of Afrofuturism is the concept of the Black Fantastic which is described as “works of speculative fiction that draw from history and myth to conjure new visions of African diasporic culture and identity,” and has already become popular in fashion scholarship. [26, 27] One example of Afrofuturistic dress that maintained historical accuracy and cultural relevance was the red Himba style wig. This wig utilizes shea butter and red clay to form locs that are protected from debris and harsh sun, sealed at the ends with puffs made from wool or other animal fur. This character, an Elder woman in Wakanda, wears a full red skirt and floor-length shawl trimmed in the fictional alphabet of Wakanda, inspired by Nsibidi lettering in southeastern Nigeria and designed by Hannah Beachler, who introduces the futuristic element into these pieces, allowing for a modern perspective on a historical practice. At the 2025 Costume Society of America Conference, Carter stated in her virtual keynote address that “It wasn’t enough to just research the tribes and show them in their indigenous forms, we also needed to show how they honored their ancestry, but also wanted to use modern technology through their dress.” [28]

Himba Tribal Edler Costume for the film Black Panther, designed by Ruth E. Carter,

photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum.

Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Another dynamic example of Afrofuturism as expressed through dress in Black Panther were the Dora Milage warrior women costumes. The color red and detailing within their costumes were inspired by the Masai tribe in Kenya, while the warrior elements of their costumes were inspired by the Agojie, an all-women military regiment in the Dahomey Kingdom, dating back to the 17th century. Carter (2025) stated, “We wanted their armor to feel like jewelry. We wanted there to be a new way of training the eye to look at beauty under different standards.” [29] The stories told through these pieces are memorable, not just because they are aesthetically pleasing with attractive technologies and bold hues, but because they are memories made tangible in and of themselves.

A newly welcomed term, Afronowism, coined by Stephanie Dinkins, refers to “the unencumbered black mind [as] a wellspring of possibility.” [30] Much like the griottes of the past, Dinkins credits her grandmother as the primary source of inspiration behind the development of Afronowism, bringing ancestral wisdom into the modern, artfully lived experience.

Although films Carter worked on such as School Daze (1988), Do The Right Thing (1989), Crooklyn (1994), and B.A.P.S. (1997) are classics of the past, they were hyper-relevant and modern, reflecting the realness of the Afronow during the time of their production and release. This demonstrates that Carter has had her thimble on the pulse of African diasporic culture across dimensions. Most recently, in Ryan Coogler’s film Sinners (2025), Carter designed what will surely be honored as one of the most iconic displays of historic, present, and futuristic dress practices in the history of film. During the character Sammy’s (Miles Canton) song, “I Lied To You,” Carter channels her inner fashion griotte by inserting characters adorned in Zaouli-inspired dress from Cote d'Ivoire, Alvin Ailey signature red and flowy dancewear, as well as funk- and space-themed garb from the musicians of the late 1970s into the early 1980s. She incorporates 1990s women’s hip-hop–inspired streetwear and accessories, early 2000s Compton-inspired tall-tees, and more, making for a joyfully overwhelming experience, like a Black fashion history “Where’s Waldo?”.

Carter’s approach to costuming, dress, and identity aligns with Dinkins’ view of Afronowism as she asks, “how [can] we liberate our minds from the infinite loop of repression and oppositional thinking America imposes upon those of us forcibly enjoined to this nation?” [29] In the images below, there are hand-written ‘thank you notes’ to Ruth, showing appreciation for her influence and impact on the lives of their writers, emphasizing that her work maintains present admiration and continues to liberate generations past, present, and future. In the words of the characters Mister Señor Love Daddy in Do The Right Thing (Samuel Jackson) and Dap Dunlap in School Daze (Laurence Fishburne), I believe Carter has been asking the costume design industry for decades, not only to look back and fly forward but also to please, “WAKE UP!”

Afronowism - Present-Day Gratitude and Impact of Carter’s Fashion in Film

A newly welcomed term, Afronowism, coined by Stephanie Dinkins, refers to “the unencumbered black mind [as] a wellspring of possibility.” [30] Much like the griottes of the past, Dinkins credits her grandmother as the primary source of inspiration behind the development of Afronowism, bringing ancestral wisdom into the modern, artfully lived experience.

Although films Carter worked on such as School Daze (1988), Do The Right Thing (1989), Crooklyn (1994), and B.A.P.S. (1997) are classics of the past, they were hyper-relevant and modern, reflecting the realness of the Afronow during the time of their production and release. This demonstrates that Carter has had her thimble on the pulse of African diasporic culture across dimensions. Most recently, in Ryan Coogler’s film Sinners (2025), Carter designed what will surely be honored as one of the most iconic displays of historic, present, and futuristic dress practices in the history of film. During the character Sammy’s (Miles Canton) song, “I Lied To You,” Carter channels her inner fashion griotte by inserting characters adorned in Zaouli-inspired dress from Cote d'Ivoire, Alvin Ailey signature red and flowy dancewear, as well as funk- and space-themed garb from the musicians of the late 1970s into the early 1980s. She incorporates 1990s women’s hip-hop–inspired streetwear and accessories, early 2000s Compton-inspired tall-tees, and more, making for a joyfully overwhelming experience, like a Black fashion history “Where’s Waldo?”.

Carter’s approach to costuming, dress, and identity aligns with Dinkins’ view of Afronowism as she asks, “how [can] we liberate our minds from the infinite loop of repression and oppositional thinking America imposes upon those of us forcibly enjoined to this nation?” [29] In the images below, there are hand-written ‘thank you notes’ to Ruth, showing appreciation for her influence and impact on the lives of their writers, emphasizing that her work maintains present admiration and continues to liberate generations past, present, and future. In the words of the characters Mister Señor Love Daddy in Do The Right Thing (Samuel Jackson) and Dap Dunlap in School Daze (Laurence Fishburne), I believe Carter has been asking the costume design industry for decades, not only to look back and fly forward but also to please, “WAKE UP!”

Left: Gamma Ray Sketch for the film School Daze, designed by Ruth E. Carter, , photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum. Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Right: Tina’s Costume worn by actress Rosie Perez in the film Do The Right Thing, designed by Ruth E. Carter, photo by Cydni Meredith Robertson, Indianapolis Children’s Museum. Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Costume Design Exhibit. June 2025.

Researcher’s Reflection and Bio

I had three distinct pleasures to interact with Ruth E. Carter’s work in 2025 that led to the publication of this reflection essay and gratitude. In March 2025, I was invited to speak at the Indiana Comic and Pop Culture Convention on the topic “Ruth E. Carter - Afrofuturism in Fashion and Film: From School Daze to Wakanda.” It was at this event that I was able to gather a few personalized ‘thank you’ notes for Carter that affirmed the impact of her life’s work on the lives of those who wrote them. In June 2025, I had the privilege to hear Carter’s virtual keynote to the Costume Society of America’s Symposium at Loyola Marymount University. At this event, I gathered a few inspirational quotes that added color and life to this reflection. Lastly, in June 2025, I visited the Indianapolis Children’s Museum to explore the current exhibit on display, Ruth E. Carter: Afrofuturism in Costume Design, which features more than 60 pieces and illustrations of Carter originals from films such as Do The Right Thing (1989), Dolemite is My Name (2019), and Coming 2 America (2021). The photos in this reflection were taken from this exploratory museum visit.

Notes: Ruth E. Carter

[1] Thomas A. Hale, “Griottes: Female Voices from West Africa,” Research in African Literatures 25, no. 3 (1994): 71–91.

[2] Jayne Ifekwunigwe, Re-invoking the Griotte Tradition as a Feminist Textual Strategy, 2008.

[3] James Denbow, “Heart and Soul: Glimpses of Ideology and Cosmology in the Iconography of Tombstones from the Loango Coast of Central Africa,” Journal of American Folklore 112, no. 445 (1999): 404–423.

[4] Shaneé Yvette Murrain, “The Oxford Handbook of African American Theology,” Theological Librarianship 10, no. 1 (2017): 48.

[5] D. Appiah-Adjei, Sankofa as a Universal Theory for Dramatists (2016), ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/289534716.

[6] D. Goeller, “Fashion (Hi)stories: Poetics and Politics,” Clothing Cultures 10, no. 2 (2023): 149–161.

[7] Marta Torregrosa, Manuel Noguera, and Nélida Luque-Zequeira, “Costume Design in Film: Telling the Story and Creating Malcolm X’s Character in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X (1992),” Fashion, Style & Popular Culture, 2023.

[8] Indianapolis Children’s Museum, Malcolm X: Shaping the Image of a Leader (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Children’s Museum, 2025).

[9] L. Henry King, “Black Skin as Costume in Black Panther,” Film, Fashion & Consumption 10, no. 1 (2021): 265–276.

[10] Muhammad Salih Odeh, “Visual Identity in Costume Design of the Cinematic Queen’s Character,” International Journal of Design and Fashion Studies 4, no. 1 (2021): 228–244.

[11] Ruth E. Carter, The Art of Ruth E. Carter: Costuming Black History and the Afrofuture, from Do the Right Thing to Black Panther (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2023).

[12] S. G. Rubin, The Women Who Built Hollywood: 12 Trailblazers in Front of and Behind the Camera (New York: Astra Publishing House, 2023).

[13] B. Ishola, “Afrofuturism at the Museum of Pop Culture,” World Literature Today 97, no. 1 (2023): 8–10.

[14] J. Thompson, A Counterhistory of the Ratchet: Black Aesthetics in the New Millennium (n.p., 2024).

[15] CBS News, “Ruth E. Carter Makes History as First Black Woman to Win Two Academy Awards for Costume Design,” CBS News, March 13, 2023, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/oscars-2023-ruth-e-carter-black-woman-best-costume-design-black-panther-wakanda-forever/.

[16] Tessa Smith-Whicker and Jenna Brown, “Decolonizing Stylistic Awareness in Higher Education Contemporary Commercial Music Training: Exploring Performer–Practitioner Experiences through an Africentric Approach,” Journal of Popular Music Education 8, no. 2 (2024): 157–178.

[17] Damariyé L. Smith, Interrogating Identity in the Film Dear White People: An Examination of Afrocentrism and Eurocentrism (PhD diss., California State University, Sacramento, 2017).

[18] Mary Ellen Roach-Higgins and Joanne B. Eicher, “Dress and Identity,” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 10, no. 4 (1992): 1–8.

[19] Sandra Jackson and Angelique Macklin, “Nice & Rough: Unapologetically Black, Beautiful, and Bold,” WSQ: Women’s Studies Quarterly 43 (2015): 122–124.

[20] Clenora Hudson-Weems, Africana Womanism: Reclaiming Ourselves (Troy, MI: Bedford Publishers, 1993).

[21] Langston Hughes, Birmingham Sunday, September 15, 1963.

[22] Rumbidzai Chikafa-Chipiro, “The Future of the Past: Imagi(ni)ng Black Womanhood, Africana Womanism and Afrofuturism in Black Panther,” Image & Text 33 (2019): 1–20.

[23] “How Black Panther Marks a Major Milestone in Afrofuturism,” Time, April 12, 2018, https://time.com/5246675/black-panther-afrofuturism/.

[24] Octavia E. Butler, Kindred (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1979).

[25] Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower (New York: Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993).

[26] Ekow Eshun, In the Black Fantastic (London: Thames & Hudson, 2022).

[27] Janis Jefferies, “Razzle, Dazzle and the Black Fantastic,” TEXTILE 22, no. 1 (2024): 166–173.

[28] Ruth E. Carter, keynote address, Costume Society of America Conference, Loyola Marymount University (virtual), 2025.

[29] Stephanie Dinkins, “Afro-now-ism: The Unencumbered Black Mind Is a Wellspring of Possibility,” Berggruen Institute, November 13, 2020, https://www.noemamag.com/afro-now-ism/.

Additional Resources

Amistad. Directed by Steven Spielberg. Universal City, CA: DreamWorks Pictures, 1997. Film.

B.A.P.S. Directed by Robert Townsend. Burbank, CA: New Line Cinema, 1997. Film.

Black Panther. Directed by Ryan Coogler. Burbank, CA: Marvel Studios, 2018. Film.

Lee Daniels’ The Butler. Directed by Lee Daniels. Los Angeles: The Weinstein Company, 2013. Film.

Malcolm X. Directed by Spike Lee. Burbank, CA: Warner Bros., 1992. Film.

Marshall. Directed by Reginald Hudlin. Los Angeles: Open Road Films, 2017. Film.

School Daze. Directed by Spike Lee. New York: Columbia Pictures, 1988. Film.

Selma. Directed by Ava DuVernay. Hollywood, CA: Paramount Pictures, 2015. Film.

Sinners. Directed by Ryan Coogler. United States: Proximity Media; distributed by Warner Bros. Pictures, 2025. Film.

Sparkle. Directed by Salim Akil. Culver City, CA: Sony Pictures, 2012. Film.

Wakanda Forever. Directed by Ryan Coogler. Burbank, CA: Marvel Studios, 2022. Film.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics