Nuno Nogueira holds a BA and an MA in Fashion Design from the Lisbon School of Architecture, University of Lisbon, and a PhD in Design from the same school. He teaches Draping, Pattern Design, and Fashion Project at the Lisbon School of Architecture. His research pivots around artistic approaches to body representation in pattern design through exploratory processes implicating sensory and performative interactions. Outside academia, he often collaborates as a costume designer for dance performances.

Ines Simoes holds a BA in Painting, an AAS in Patternmaking, an MSc and a PhD in Design. Her professional activity covers fine arts, fashion and costume design, 2D and 3D pattern design. She is an Associate Professor at Lisbon School of Architecture, University of Lisbon, and the coordinator of the BA Fashion Design. Her research and writing comprise the paradigms of the body’s representation in pattern design and new approaches to teaching-learning fashion design.

The title of this essay matches its structure: reflect imparts the students’ reactions throughout experiencing one nonlinear process; reflected presents three conceptions of reflection that ground the process; reflection conveys the implications of this type of process for both teachers and students.

Reflect

In 2024, we devised the RORSCHACH project as the final assignment for 3D Pattern Design, a requirement for seniors in the three-year B.A. Fashion Design program at the Lisbon School of Architecture. Following their three semesters of flat patternmaking, students met weekly over the course of a five-week period to collaborate on this project, with our guidance as their teachers.

The brief outlined the project's steps and included four dress patterns by French costume designer Geneviève Sevin-Doering, as well as four inkblot cards by Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach. Placed above each other, the four pairs display an obvious similarity: regardless of their distinctive purposes, both are symmetrical and intriguing (Fig. 1).

The project’s main goal was to challenge students with a design process that subverts the classical and linear processes they are used to, as it did not require taking a series of actions to achieve a particular predetermined end. Instead, its emphasis was on serendipity, ensuring that the process was engaging and open-ended.

We figured, what better way to start the process than by pouring or dripping ink onto sheets of paper, then folding them in half to create symmetrical patterns with the right and left sides making a reflection of each other? (Fig. 2)

Regardless of how effortless and playful this step was, some students thought, “It was all so messy,” and since the brief specified that the unplanned inkblots would serve as clues for identifying possible dress designs made from one-piece patterns, they panicked in anticipation. One student expressed,

“You could see that it was an assignment that required a lot of thought, especially thinking outside the box. We weren’t supposed to follow the linear rules we had learned in previous semesters. So I thought, if I approach it with a more positive mindset, it might work. I’ll just let the inkblots turn out however they will.”

Other students were enthralled by the opportunity to break the rules of flat patternmaking. Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that they were all unsure of “how they were going to work on it, how to start from ‘something’ that seemed to be ‘nothing.’”

Reflect

In 2024, we devised the RORSCHACH project as the final assignment for 3D Pattern Design, a requirement for seniors in the three-year B.A. Fashion Design program at the Lisbon School of Architecture. Following their three semesters of flat patternmaking, students met weekly over the course of a five-week period to collaborate on this project, with our guidance as their teachers.

The brief outlined the project's steps and included four dress patterns by French costume designer Geneviève Sevin-Doering, as well as four inkblot cards by Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Hermann Rorschach. Placed above each other, the four pairs display an obvious similarity: regardless of their distinctive purposes, both are symmetrical and intriguing (Fig. 1).

The project’s main goal was to challenge students with a design process that subverts the classical and linear processes they are used to, as it did not require taking a series of actions to achieve a particular predetermined end. Instead, its emphasis was on serendipity, ensuring that the process was engaging and open-ended.

We figured, what better way to start the process than by pouring or dripping ink onto sheets of paper, then folding them in half to create symmetrical patterns with the right and left sides making a reflection of each other? (Fig. 2)

Regardless of how effortless and playful this step was, some students thought, “It was all so messy,” and since the brief specified that the unplanned inkblots would serve as clues for identifying possible dress designs made from one-piece patterns, they panicked in anticipation. One student expressed,

“You could see that it was an assignment that required a lot of thought, especially thinking outside the box. We weren’t supposed to follow the linear rules we had learned in previous semesters. So I thought, if I approach it with a more positive mindset, it might work. I’ll just let the inkblots turn out however they will.”

Other students were enthralled by the opportunity to break the rules of flat patternmaking. Nevertheless, it’s fair to say that they were all unsure of “how they were going to work on it, how to start from ‘something’ that seemed to be ‘nothing.’”

Fig. 1 (top) GENEVIÈVE SEVIN-DOERING patterns, 1981-1994 (bottom) HERMANN RORSCHACH inkblots, 1921

Fig. 1 (top) GENEVIÈVE SEVIN-DOERING patterns, 1981-1994 (bottom) HERMANN RORSCHACH inkblots, 1921“The project’s main goal was to challenge students with a design process that subverts the classical and linear processes...”

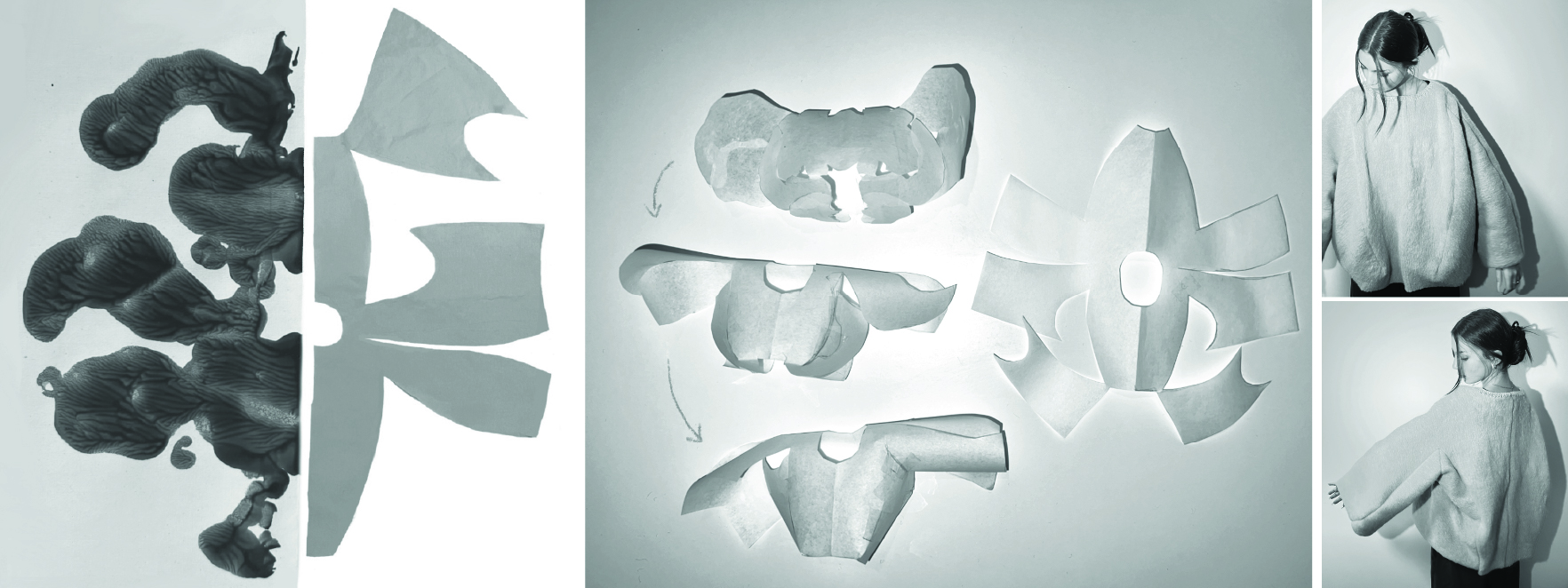

At that point, the process involved folding the traced blots in various ways to explore how they could be transformed into potential garments, tallying with another goal of the RORSCHACH project. Through the interplay of folds—folding, unfolding, refolding, with each fold acting and reacting on another—it became clear to the students that some parts of the traced blots resembled specific sections of a pattern. However, as one student pointed out, “what about the rest of the blot[s]?”

Fig. 2 Inkblots by third-year students

Fig. 2 Inkblots by third-year studentsBased on the students' tacit knowledge, it was evident that the process entailed simplifying the shapes of the traced blots, either by enlarging or discarding some areas, until the one-piece patterns seemed right; by drawing on their bodily perception, the students also considered how the body moves inside the garments throughout the editing process. (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3 From inkblot to pattern to sweatshirt (by Sofia Costa)

Naturally, not all students had the same reaction to this assignment: some loathed it, some loved it, and some endured it with indifference. Manifestly, not all outcomes were surprising, design-wise; however, by engaging students in a project that merges the actions of making-thinking-drawing as one, they were able to achieve unpredictable outcomes that otherwise wouldn't have been reached.

Regarding the pants one student designed during this process, she mentioned, “maybe I could have made it in flat patternmaking. But it never would be so over the top. Because I think I got the balance between its exaggerated silhouette and wearability.” (Fig. 4)

Regarding the pants one student designed during this process, she mentioned, “maybe I could have made it in flat patternmaking. But it never would be so over the top. Because I think I got the balance between its exaggerated silhouette and wearability.” (Fig. 4)

Fig. 4 From inkblot to pattern to pants with box pleat (by Sonia Ribeiro)

Fig. 4 From inkblot to pattern to pants with box pleat (by Sonia Ribeiro)Reflected

The theoretical and practical implications of the RORSCHACH project are grounded in three conceptions of reflection. The first and most obvious is the conception of the human body as a mirrored, spatial configuration relative to an imaginary vertical plane or axis. According to German mathematician and philosopher Hermann Weyl, the symmetry of left and right, i.e. bilateral symmetry, is a geometric concept that presupposes that two points share the same relation to a given plane, each standing on the opposite side of that plane, through reflection. Thus, reflection “is that mapping of space upon itself… that carries [an] arbitrary point into its mirror image.” [1]

Because bilateral symmetry is so prominent in the way we perceive the structure of the human body, it has several practical implications in the designing and construction of dress. In patternmaking and draping, for example, center front and center back are auxiliary lines used when cutting the fabric on fold, or even when classifying a garment as asymmetrical. Therefore, the first step of the RORSCHACH project, which entails the creation of unplanned but symmetrical inkblots, arises from the idea that, as long as bilateral symmetry is respected, any drawing is a possible dress pattern.

The second conception of reflection is elicited when students explore the potential of the inkblots through folding. The open-ended nature of the project required a thinking process that American philosopher and professor Donald Schön coined in 1983 known as reflection-in-action, “[an] intuitive performance [where] reflection tends to focus interactively on the outcomes of action… and the intuitive knowing implicit in the action.” [2] Schön admits that reflection-in-action presupposes the use of one’s tacit knowledge, a phrase introduced by Hungarian-British polymath Michael Polanyi in 1966. Polanyi’s idea that “we can know more than we can tell,” matching the second step of the RORSCHACH project, draws a parallel to the internalized knowledge of the body-dress relationship acquired by students throughout the B.A. program. [3]

The validity of the RORSCHACH project—and any design project using nonlinear processes—lies in its ability to encourage students to freely reflect [on] their intimate perspectives about designing garments. A third conception of reflection emerges when [some] students reconsider their preconceived beliefs about fashion and dress. According to American philosopher John Dewey, the process by which “[an] active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it, and the further conclusions to which it tends” is called reflective thought. [4] What Dewey suggests here is that any experience, particularly in a pedagogical context, should stimulate students to reflect on the connection between the basis of a conviction and its consequences.

Even though Dewey does not mention the potential of open, nonlinear processes to expand one’s view about a subject, he explicitly sustains that every reflective operation involves “a state of perplexity, hesitation, doubt; and an act of search […] directed toward bringing to light further facts which serve to corroborate or to nullify the suggested belief.” [5]

It would be dishonest to state that the RORSCHACH project alone caused students to deeply reflect on their identities as fashion designers-to-be. After all, it takes a village to raise a child, as the proverb goes. But as one student stated:

“Nowadays, the amount of advertising, communication, and things that are always influencing us is overwhelming. And in these types of processes, there is little outside that influences us.”

Reflection

The RORSCHACH project devised for 3D Pattern Design reflects our interest in nonlinear processes. We believe that different pedagogical approaches must be adopted, unlike the classical and linear processes employed from our former college professors that are still in use. [6] For some time now, we have been experimenting with alternative processes, merging the actions of ideation and materialization as one. The idea behind our pedagogical experimentations is to enable students to surpass internal and external preconceptions and to reflect their true selves in their work.

Admittedly, the RORSCHACH project was the product of a whim—how could we not be fascinated by the beauty of Rorschach’s inkblots and instantly associate them to Sevin-Doering’s one-piece patterns?

Initially, the project's variability and unpredictability posed challenges for all involved as students were unsure of where to begin the process without knowing the solution, and teachers were uncertain of how to provide useful suggestions.

Eventually, those uncertainties enabled suspending [some] hierarchies between everyone involved. With no definitive correct or incorrect answers, the students found themselves on equal ground with the teachers. And so, students began to rely on their ability to summon an internalized knowledge of the body-dress relationship, as well as their resilience in exploring various solutions.

Admittedly, the project demanded an agile and unassuming mindset from the teachers, as implementing open-ended projects based on nonlinear processes requires all involved to embrace the surprising outcomes, whether promising or undesirable. This, in turn, proved to boost the students' confidence in their reasoning skills.

Of course, a few students did resist this pedagogical approach, questioning its purpose. However, given the majority of the outcomes, we trust that serendipity is a key factor in designing, as it might bring about the reflected self.

Ultimately, projects like the RORSCHACH, which involve working side by side with students, allow us to reflect continuously on our role as teachers.

Notes: Reflect Reflected Reflection

[1] Hermann Weyl, Symmetry (Princeton University Press, 1952), 5, https://abel.math.harvard.edu/~knill/teaching/mathe320_2017/blog17/Hermann_Weyl_Symmetry.pdf

[2] Donald Schön, The Reflective Practitioner – How Professionals Think in Action (Routledge, 2016[1983]), 56.

[3] Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension (The Chicago University Press, 2009[1966]), 4.

[4] John Dewey, How We Think (D. C. Heath & Co. Publishers, 1910), 6, https://bef632.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/dewey-how-we-think.pdf

[5] Dewey, How We Think, 9.

[6] Steven Faerm, “Why Art and Design Higher Education Needs Advanced Pedagogy,” M/I/S/C Magazine (2013), https://miscmagazine.com/author/sfaerm/

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics