Dr. Julia Petrov is Curator of Daily Life and Leisure at the Royal Alberta Museum, and is adjunct academic staff at the University of Alberta. She researches and writes about dress history, gender, and museology. She is the author of Fashion, History, Museums: Inventing the Display of Dress (Bloomsbury, 2019).

Imagination, life is your creation

I was born in the dying years of the Soviet Union and grew up amidst legendary queues and increasing shortages of consumer goods. Although my parents were middle class, and we lived in the capital, Moscow, which to some degree protected us from the hardships faced by people outside of the country’s urban centers, our family means were limited. Apart from a few stuffed animals and some random pieces of toy furniture (a child-size wooden chair, a tiny piano, and a doll crib oddly out of scale to anything else), at playtime, I had to make do with a small number of odd dolls.

My prized possession, named Lilya after the distant relative in Minsk who gave her to me, was a large doll dressed in a folk-style costume of lace-trimmed blouse and floral skirt. Her left arm was loose in its socket, which eventually led to my mother throwing her away while I was out for the day at school. But her prismatic blue eyes, fringed with long eyelashes, would close when she lay down (an engineering mystery that fascinated me almost as much as my classic nevalyashka doll’s ability to stand up when knocked down), and I learned to braid by playing with her thick, blonde hair.

I also had a much smaller plastic doll with curly auburn hair. I do not remember her ever having had any clothes, so I learned to modestly cover her nakedness by tying a selection of colorful plastic bags over her front (I was yet too young to learn to sew). Later, when I was closer to school age, family friends in West Germany sent me three Erna Meyer figures (all Victorian children) as well as two soft-bodied dolls dressed in athletic clothing. One of these was blonde and had an uncanny resemblance to my real-life best friend, so she was duly named Masha; I gave my best friend the brunette matching doll in remembrance of me, even though she didn’t look like me. All of my dolls looked like young girls, with pouting baby faces and unsexed bodies.

Bottom: The author, accompanied by her mother, holding her doll Masha; Buddha visible behind. Moscow, 1990, days before emigrating.

All images courtesy of the author.

Luckily, for the purposes of playing out more grown-up themes, I also had a hand-me-down molded plastic military figure, probably modeled after the “good soldier Svejk,” a Czech literary and film character very popular in Russia during my parents’ generation. Naturally, he was paired off with the most beautiful doll of the lot: a small antique pincushion doll with a porcelain torso and arms but a lower body made of a cardboard dome covered with sky-blue satin, in imitation of a ruched crinoline skirt. This glamorous but unarticulated pair presided over my improvised dollhouses - forts made from cushions and cardboard.

I also enjoyed playing with the bronze Tibetan Buddha that sat incongruously on top of my parents’ antique writing desk; I would unfold the desk, climb on top of its worn green leather writing surface, and take off Buddha’s crown. The lotus flower he held was also removable; I delighted in putting its stem back into the perfect perforation in his palm.

My parents rarely took me along with them to social events, but once, when I was 6 or 7, we all attended a party held by family friends. The couple had a daughter who was a little older than me, and that might have been why I was also invited. The family was better off than us: they lived in a large apartment and had access to all kinds of exclusive aspects of the Western lifestyle that were largely out of reach even for my bourgeois-minded parents. Implicitly understanding our straitened financial circumstances, I had never even asked my parents to have a taste of the colorful juice from concentrate that swirled temptingly around the dispensers at delis we occasionally visited, so the fact that orange Fanta was served at this party was a signal comprehensible even to me of the impossibly high rank of social elite to which this family belonged. The Fanta tasted horrible - chemical sweetness attacked my tongue on a rush of carbon bubbles. But another forbidden Western luxury I spotted that day changed my life forever.

In pride of place, on a table in the center of the room, was a Barbie. Actually, given that she was a brunette, she might not have been Barbie herself - maybe she was a Midge, or maybe she was an Eastern-European imitation of a Barbie. She may have been imported after a trip abroad, or perhaps she was one of the few Western toys available at elite Moscow toy stores during perestroika [1]. Nevertheless, she was exotic and forbidden. Although her stiff limbs, tiny waist, and pointed toes were grotesque, she fascinated me - she threw into harsh relief the bulbous ugliness of my baby girl dolls. Her closest parallel in my own toy box was the boudoir doll, which was, technically, only half a doll! I wanted the Barbie, and yet, I knew that my parents would never be able to give me one of my own.

It had taken years, but this was the moment that my class consciousness was cemented; against the hopes of Party propagandists, however, it did not create in me a distaste for the inequalities of the West. Instead, that Barbie doll made me realize that I wanted to be part of the ruling elite - the hypocrisy of the socialist state be damned, I wanted the finest things in life, and to my 7-year-old mind, that meant owning a Barbie.

It would be wrong to assume that I was then filled with a counter-Revolutionary zeal. I did not wrestle that Barbie away from her owner, or steal it, to demonstrate my understanding of the inequality and exploitation of the capitalist West. In fact, I’m not sure I even played with her much that afternoon. I had internalized the passive dejection of knowing my inferior social status a long time ago. At home, I continued to play with my awkward, semi-clothed, ragtag band of deformed dolls. But Barbie had entered my life, and there was no going back.

I also enjoyed playing with the bronze Tibetan Buddha that sat incongruously on top of my parents’ antique writing desk; I would unfold the desk, climb on top of its worn green leather writing surface, and take off Buddha’s crown. The lotus flower he held was also removable; I delighted in putting its stem back into the perfect perforation in his palm.

Come on Barbie, let’s go party

My parents rarely took me along with them to social events, but once, when I was 6 or 7, we all attended a party held by family friends. The couple had a daughter who was a little older than me, and that might have been why I was also invited. The family was better off than us: they lived in a large apartment and had access to all kinds of exclusive aspects of the Western lifestyle that were largely out of reach even for my bourgeois-minded parents. Implicitly understanding our straitened financial circumstances, I had never even asked my parents to have a taste of the colorful juice from concentrate that swirled temptingly around the dispensers at delis we occasionally visited, so the fact that orange Fanta was served at this party was a signal comprehensible even to me of the impossibly high rank of social elite to which this family belonged. The Fanta tasted horrible - chemical sweetness attacked my tongue on a rush of carbon bubbles. But another forbidden Western luxury I spotted that day changed my life forever.

In pride of place, on a table in the center of the room, was a Barbie. Actually, given that she was a brunette, she might not have been Barbie herself - maybe she was a Midge, or maybe she was an Eastern-European imitation of a Barbie. She may have been imported after a trip abroad, or perhaps she was one of the few Western toys available at elite Moscow toy stores during perestroika [1]. Nevertheless, she was exotic and forbidden. Although her stiff limbs, tiny waist, and pointed toes were grotesque, she fascinated me - she threw into harsh relief the bulbous ugliness of my baby girl dolls. Her closest parallel in my own toy box was the boudoir doll, which was, technically, only half a doll! I wanted the Barbie, and yet, I knew that my parents would never be able to give me one of my own.

It had taken years, but this was the moment that my class consciousness was cemented; against the hopes of Party propagandists, however, it did not create in me a distaste for the inequalities of the West. Instead, that Barbie doll made me realize that I wanted to be part of the ruling elite - the hypocrisy of the socialist state be damned, I wanted the finest things in life, and to my 7-year-old mind, that meant owning a Barbie.

It would be wrong to assume that I was then filled with a counter-Revolutionary zeal. I did not wrestle that Barbie away from her owner, or steal it, to demonstrate my understanding of the inequality and exploitation of the capitalist West. In fact, I’m not sure I even played with her much that afternoon. I had internalized the passive dejection of knowing my inferior social status a long time ago. At home, I continued to play with my awkward, semi-clothed, ragtag band of deformed dolls. But Barbie had entered my life, and there was no going back.

Middle: The author next to a tea cozy doll (baba na chainik). Calgary, 1990.

Bottom: The author as Barbie princess. Lynn, c. 1993.

All images courtesy of the author.

“I have no concerns about Barbie’s influence on me. She enabled me to realize my ambitions and live as my authentic self.”

Life in plastic, it’s fantastic

The 1980s were a bleak decade to live in Russia. A series of increasingly old and decrepit Communist Party Chairmen had ensured the total stagnation of the economy, resulting in widespread shortages and rationing. Young people like my parents struggled to make ends meet even on a guaranteed income in a planned economy, and the increased transparency of Gorbachev’s glasnost made it even clearer that there was no hope for the next generation if the corrupt and hypocritical system was to continue. Terrified by the fallout from Chernobyl, but emboldened by the fall of the Berlin Wall, my parents were determined to escape. Drawing on family connections, they were able to obtain entry to Canada. We left the Soviet Union in September 1990, with 6 suitcases and $200 Canadian dollars - all that we were allowed to take with us to start a new life. I was eight years old. In the little backpack that I carried with me on the plane, I packed my own treasures, including my blonde West German athlete doll, and Erna Meyer figures [2].

For the first six months, we lived in the basement of the relative who had sponsored our immigration. The suitcases lay, permanently open, on the floor, my parents slept on a mattress on the floor in the spare room, and I slept on the taupe velvet sectional in the wood-paneled rec room. My parents found entry-level jobs, and I started school. Apart from the contents of my imported rucksack, I also played with the other denizen of that basement: a quilted tea cozy doll, dressed in a Russian folk ensemble.

These privations didn’t last long. As soon as my parents began getting paid at their new jobs (gas station attendant and nursing home assistant), they made my doll dreams come true. I soon received a pink cardboard box with a Barbie of my very own. Mattel had named her “My First Barbie,” and perhaps my parents took that moniker literally when they selected her at the store. She was dressed in an iridescent princess gown with a tiara. The colors and textures of her outfit fascinated me, and I was delighted when, a couple of years later, my grandmother found a similar dress at a jumble sale for me to wear as a costume.

One winter day, my parents hauled a huge box inside. They maneuvered it down the stairs and revealed the surprise: it was a Barbie dollhouse! Originally released in 1984, this four-room pink mansion (the Barbie Glamour Home) had a spiral staircase on one side, an imitation wicker swing on the other, and a rooftop patio. My father (an aerospace engineer) dutifully put it together for me, although we had trouble with the stickers that were meant to cover up the plastic beams that held it together, and some were forever upside down or wrinkled after our botched assembly. Even with its flaws, it was still a long way from the interiors in which I really lived. The dream of a better life, as painted by Barbie, was beginning to come true. A few items of furniture also followed, but I found them awkward and illogical, given that the dollhouse had images printed on its walls of the contents, and these didn’t correspond to the furnishings I now owned.

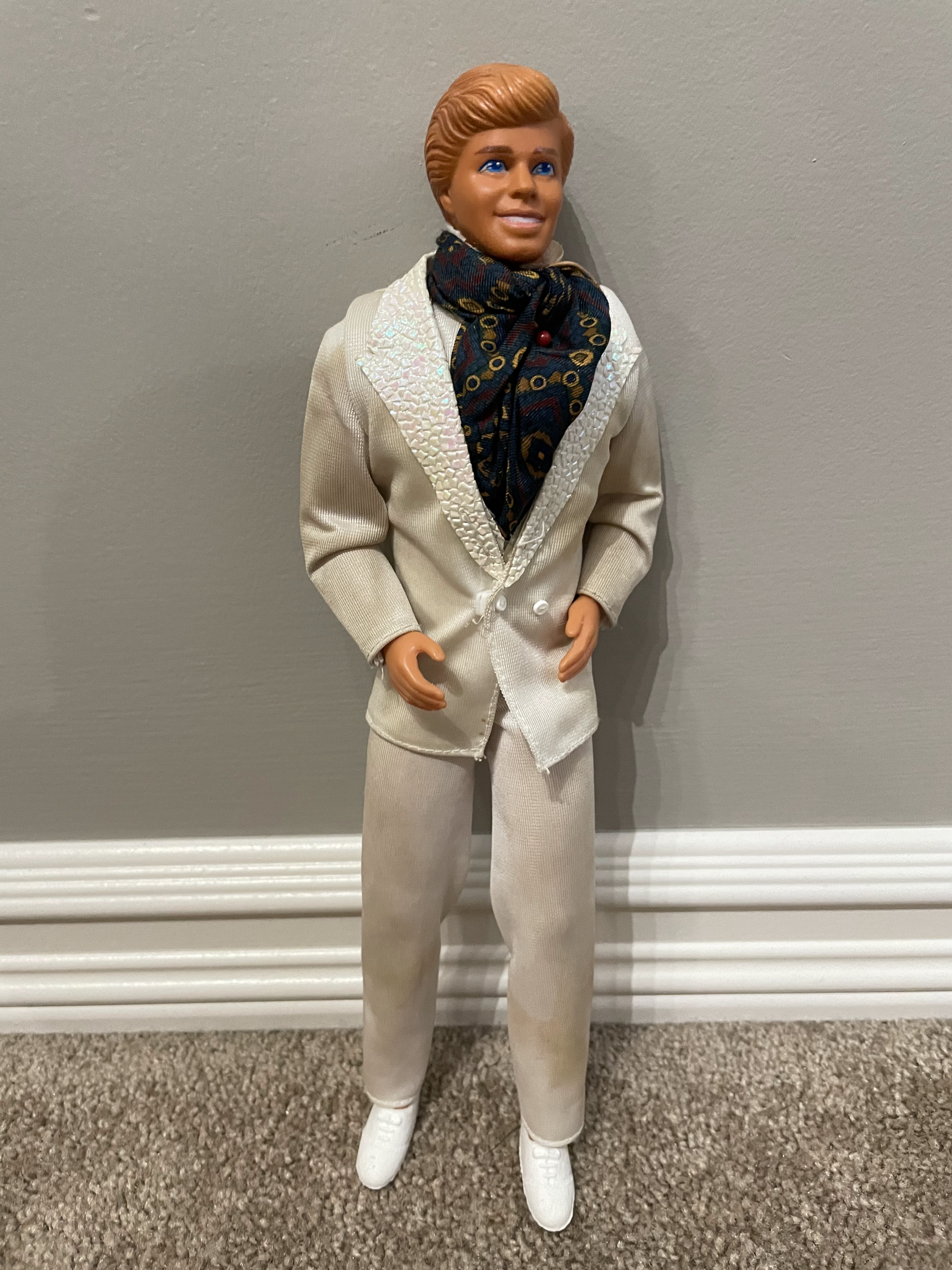

Not long afterwards, I received two more inhabitants for the mansion: a gift set of Dance Magic Barbie and Ken, dressed in iridescent white ballroom outfits. Ken’s hair changed color with the application of cold or hot water, and Barbie’s gown converted to a tutu; their fashion options seemed endless. Thereafter, family members always had gift ideas to fall back on at Christmastime and my birthday: my uncle scored a particular coup when he obtained the last “Totally Hair” Barbie in the city, in her Pucci-inspired mini-dress, after driving around all the city’s toy stores in a blizzard during the frigid winter of 1992.

Totally Hair Barbie, 1992.

Totally Hair Barbie, 1992.Image courtesy of Mattel.

At first, I was content to play with the dolls as they were presented. I even took a particular pride in keeping their outfits pristine and associated with their original wearers. However, as my collection grew, and was increasingly augmented by second-hand Barbies (and Barbie knock-offs), who wore scraps of clothing or nothing at all, even the packs of Barbie outfits available in stores no longer satisfied me.

You can brush my hair, undress me everywhere

In the summers, when school was out, my parents flew me to Boston, to stay with my grandparents and practice my Russian. My grandmother and her friends enjoyed Saturday morning “yard sailing,” (pun intended) where we would pile into the car, armed with the classified page of the paper and an address of a promising garage sale in a tony neighborhood. These experts knew, from pulling up to the curb, whether it was worth getting out; estate sales were vetoed on account of their inflated prices. In those days, the older residents of towns like Marblehead and Swamscott were selling vintage furnishings and household goods from the 1940s to the 1960s, and treasures could be had for just a few dollars. After the first sale, we would follow the homemade signs on the streets to others, sometimes going as far as Salem; if it hadn’t been a good day and it was still early enough, we would return home via the nearby flea market. My grandfather would then be entertained by a show-and-tell of our finds over lunch.

Naturally, I was always on the lookout for Barbies, but my grandmother had started to teach me needlecrafts, and I slowly began to also accumulate material to upgrade my Barbies’ standards of living. The first thing we made was some bedding (the bed itself being an upcycled polystyrene tray from some supermarket meat), but doilies, handkerchiefs, and small scraps of fabric proved useful for creating clothes. I eagerly snapped up vintage napkins, hem tape, lace, buttons, and headscarves at yard sales for a few cents each. Some of these notions are still in my stash to this day.

Another favorite destination in the summers was the Museum of Fine Arts. Knowing my love of dolls, my family pointed out a book in the gift shop: a Dover reprint of paper dolls originally published in the Boston Herald in the mid-1890s. Now that I had discovered crafting, I found paper dolls limiting to my imagination, but looking at the figures of the blonde and brunette models in their corsets and petticoats, I realized that their silhouettes and stiff posture were uncannily similar to my Barbies. In a sudden cognitive leap, I understood why I found the results of my sewing experiments making modern clothing for my dolls unsatisfying - their bodies were all wrong for contemporary styles. Another book purchase made that day was Joan Nunn’s Fashion in Costume, and her spidery line drawings of historic clothes were to become my guides to creating outfits for my Barbies which suited their corseted shapes.

And so, as a tween, without even knowing that’s what I was doing, I began to do research in dress history. I would carefully study a doll’s face and hair to determine the most suitable period for them, then consult my books for inspiration, and dig through my stash for appropriate materials. Partly because I came to Barbies so late, but mostly because I enjoyed the creative outlet and historical context, I continued to regularly sew costumes for my dolls well into my teens.

Middle: Unwrapping a French translation of James Laver’s Costume and Fashion: A Concise History (Thames and Hudson) from a relative in France. Lynn, December 1996.

Bottom: The author with her creations. Lynn, 1996 and 1999.

All images courtesy of the author.

I’m a Barbie girl, in a Barbie world

Being an introverted only child, I had no context for gauging whether my hobbies were normal. I continued with sewing because I liked it, and my passion and growing knowledge won over anyone who might have objected that I was too old to play with dolls. I was also fortunate enough to be surrounded by caring adults who nurtured my interests, including giving me reference books or sewing materials, and sharing opportunities to view historical costumes on display.

When I was 16, the local open-air living history museum hosted a fashion show, put on by the Vancouver-based curator and collector Ivan Sayers. My mother saw the ad in the paper, and bought us tickets. For two hours, models dressed in historical costumes from Sayers’s collection promenaded in the upstairs hall of an Edwardian prairie hotel, as he lectured about a century of fashion. I was stunned: here was a respectable middle-aged man who made a living doing what I was doing for dolls, but in real life?!?! Coming from a deeply conventional family of engineers, doctors, and academics, I had no idea that it was even possible to make a career out of fashion history that wasn’t designing costumes for stage and screen (the performing arts were looked on with great suspicion in my family). The seed was planted there and then - perhaps I could make Barbie play pay?

It took many more years for me to become comfortable with the idea of a career path in museums and academia, specializing in the history of dress. For me, play was incompatible with professionalism, and I had internalized what my fellow Canadian fashion curator Alexandra Palmer has noted as the negative stereotype of fashion curators as “style-obsessed ladies and gay men playing dress-up with large dolls” [3]. But looking back, it is undeniable that my years of costuming Barbie had been a form of apprenticeship.

Much has been written about Barbie, maligning her negative influence on young girls' understanding of their bodies and their prospects [4], but outside of the rigid parameters of a controlled psychological experiment, the reality of imaginative play is more complex [5]. While Soviet propagandists would certainly have disapproved of Barbie’s consumerist appeal, and my parents may have had doubts about the long-term feasibility of my choice of career, I have no concerns about the influence that Barbie had on me. She enabled me to realize my ambitions and live as my authentic self.

I made my last Barbie outfit when I was 27. I was working at a university in my dream job: lecturing on the history of fashion, and also curating a large teaching collection of clothing and textiles. My colleague and I were clearing out the workroom, and discovered a forlorn naked doll on a shelf. She might not have been a Barbie - perhaps she was a vintage Midge or one of Barbie’s other friends; she had strawberry blonde hair in tight curls to her shoulders, and I immediately envisioned her in an 1840s Romantic-era gown. I took her home and dug through my fabric stash until I found the perfect blue-and-white gingham to create a dress based on historic fashion plates. Appropriately attired, she was then returned to the bookshelf. My (former) colleague recently undertook another reorganization of the workroom, and gifted the doll to me in remembrance of our time working together. To me, the doll also represents the trajectory of my life: the choice my parents made to leave the deprivation of the Soviet Union for a better life in the West, which enabled me to follow my passion.

Top: Totally Hair Barbie was transformed into an 1860s lady, her hair contained in a snood.

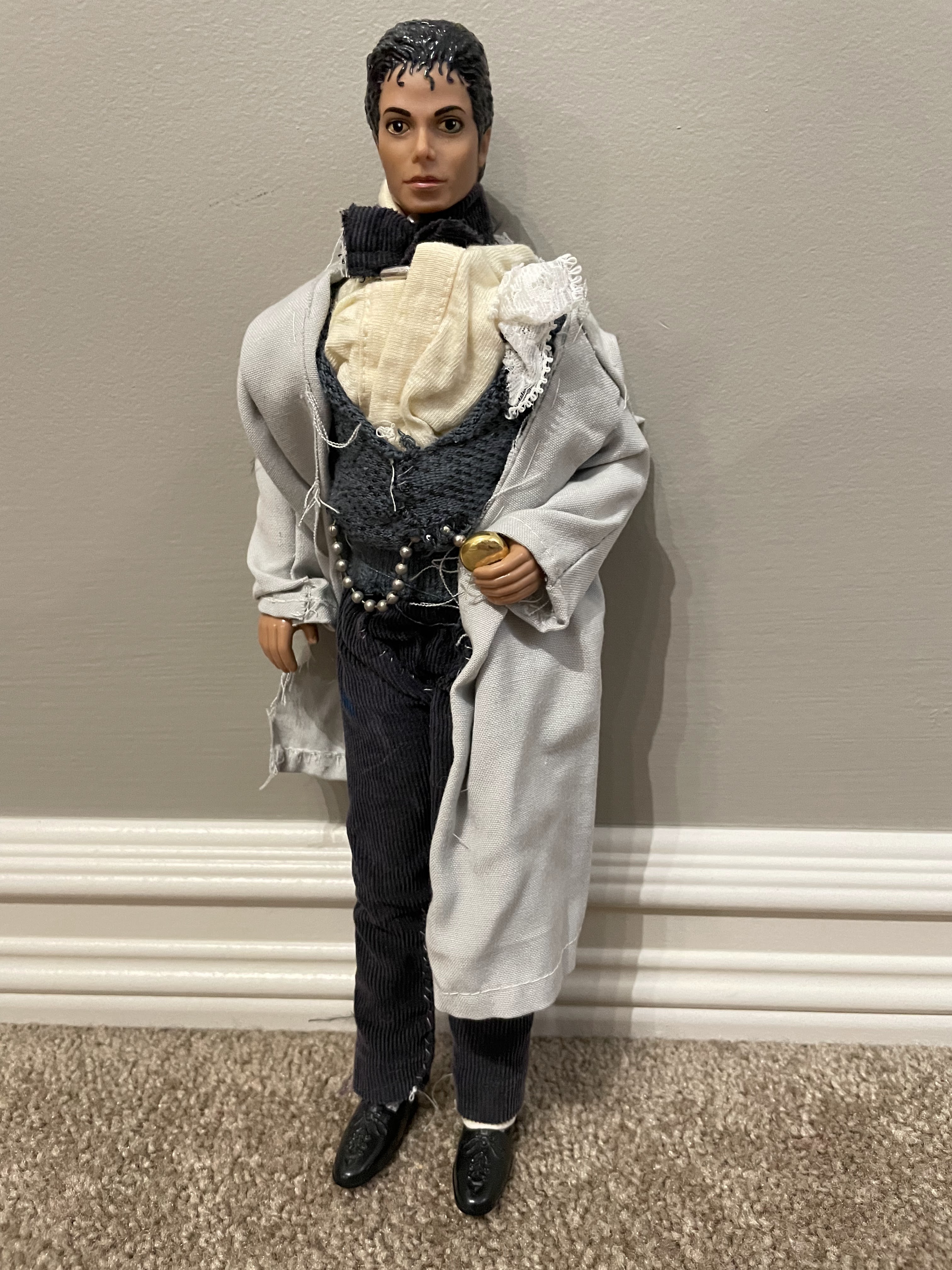

Top: Totally Hair Barbie was transformed into an 1860s lady, her hair contained in a snood. Second from top: This vintage Michael Jackson figure was purchased at the Lynn flea market in the mid-1990s, along with two New Kids on the Block figures. His original sparkly socks and shoes are visible under his trousers. My tailoring skills left a lot to be desired, and although the gender disparity among my collection bothered me, I didn’t often attempt sewing suits.

Second from bottom: Dance Magic Ken; his original suit has been accessorized with an Ascot.

Bottom: My last Barbie, 2009.

All images courtesy of the author.

Postscript

It is late 2023, a quarter century after my first encounter with Barbie. Due to the war with Ukraine, Western film companies do not distribute movies like Barbie (2023) in Russia; the country’s Culture Ministry insists that the blockbuster hit doesn’t meet the nation’s traditional moral values and wouldn’t allow licenses to screen it anyway. The Ministry of Education had earlier proposed a ban on Barbie and her friends for allegedly being sexually inappropriate, an idea recently echoed by firebrand politicians.

Meanwhile, as I was writing this essay, I received word that my book about the history of fashion exhibitions has been published in translation. The Russian-language cover features Venus de Milo dressed in a suit, wearing sunglasses, a nose ring, and large headphones, all in shades of pink. I didn’t have any input in the design, but I appreciate its subversive ideological undercurrent.

Plus ça change.

Notes: Pink is a Tint of Red

[1] See Duijn, 2019.

[2] I threw out or gave these away about ten years ago, but by kismet, another one found its way to me this year - it was a stowaway in a vintage 1:12 scale dollhouse that I purchased secondhand with the intention of restoring it.

[3] Palmer, 2008: 47-48.

[4] See: Kuther and McDonald 2004; Dittmar, Halliwell, and Ive, 2006; Sherman and Zurbriggen 2014; Nesbitt et al, 2019.

[5] See: Wright, 2003.

Additional References

Aqua. (1997). Barbie Girl [song]. Aquarium. Universal; MCA Records.

Dittmar, H., Halliwell, E., & Ive, S. (2006). Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5-to 8-year-old girls. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 283.

Dujin, M. (2019) Journeying to the Golden Spaces of Childhood: Nostalgic Longing in the Online Community The USSR Our Motherland Through the Visual Image of the Soviet Toy. In: Post-Soviet Nostalgia: Confronting the Empire’s Legacies, Edited by Otto Boele, Boris Noordenbos, and Ksenia Robbe, New York: Routledge, pp.21-37.

Gerwig, G. (2023). Barbie [film]. Warner Bros.

Kuther, T. L., & McDonald, E. (2004). Early Adolescents’ experiences with, and views on, Barbie. Adolescence, 39(153).

Nesbitt, A., Sabiston, C. M., deJonge, M., Solomon-Krakus, S., & Welsh, T. N. (2019). Barbie’s new look: Exploring cognitive body representation among female children and adolescents. PloS one, 14(6), e0218315.

Palmer, A. (2008) Untouchable: Creating Desire and Knowledge in Museum Costume and Textile Exhibitions, Fashion Theory, 12:1, 31-63.

Sherman, A. M., & Zurbriggen, E. L. (2014). “Boys can be anything”: Effect of Barbie play on girls’ career cognitions. Sex roles, 70, 195-208.

Wright, L. (2003). The wonder of Barbie: popular culture and the making of female identity. Essays in Philosophy, 4(1), 28-52.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics