Dear Barbie,

Below are some shorter reflections, reactions, and responses from writers in our community who saw your movie and had something to say.

The phrase “cultural reset” has been thrown around more than average—maybe more than necessary—over the last couple of years. Cultural resets are those distinct moments in popular culture when society’s focus or perspective on things are redirected to align with what’s “in” or “trending” at the moment. Our instantaneous connectivity through social media has provided a buzzword-obsessed generation the opportunity to be made aware of culture-resetting trends faster than ever before, letting these trends run rampant and die all within what feels like a millisecond. Even the queen Barb herself, Nicki Minaj, referred to the popular phrase as “overused social media jargon.”

Some may say that Greta Gerwig’s Barbie epitomized this concept of the cultural reset—extensive marketing, noteworthy celebrity cast, social media frenzy, a track list filled with bops.

But to what degree has the movie and its subsequent “cultural reset” quality soured the disapproving masses through overexposure, and can we trace this back to a very real resentment towards all things girlhood and womanhood? Are Barbie and other heavily marketed “cultural resets” the problem, or is the Barbie backlash just a fundamental attack on girlhood? ...

![]()

Following my Barbie movie experience, I vividly remember heading to a nearby outdoor lounge to have food and drinks with some relatives. I had enjoyed the movie and was proud of my fuschia pink outfit, but as my family and I were seated, I quickly realized that there was a clear divide in the room. There were the post-Barbie viewers like myself who were proudly donned in pink from head to toe, and the non-pink wearers who gawked at those of us sporting vibrant hues of pink as if we were a part of some sort of cult. At that moment I couldn’t help but feel judged or even a bit juvenile as I noticed their disapproving eyes, which eventually turned to eyerolls, which eventually turned into laughs, scanning the sea of pink. I felt deep shame and I couldn’t figure out why.

This moment has reeled in my mind for weeks. It even dug out of my subconscious a memory of a ten-year-old, pink-obsessed me, whose parents were about to travel abroad and asked her what clothes she would like them to purchase for her. There was one condition---nothing pink. I specifically remember my dad’s exact words: “We’re done buying pink stuff for you, choose another color.” I was not equipped with the vocabulary to express how ridiculous it was that a harmless color would be banned from my wardrobe, let alone how this revelation made me feel. Was this the mark of the end of my childhood? Why would anyone hate pink??

Color should be for all, without limitations or prejudice. Any qualification that a certain color “belongs” to one gender or another is arbitrary, historically contingent, and embedded in harmful gender hierarchies.

Below are some shorter reflections, reactions, and responses from writers in our community who saw your movie and had something to say.

Marketing, Cultural Resets, and Anti-Pink Bias

By Amelyah RoachThe phrase “cultural reset” has been thrown around more than average—maybe more than necessary—over the last couple of years. Cultural resets are those distinct moments in popular culture when society’s focus or perspective on things are redirected to align with what’s “in” or “trending” at the moment. Our instantaneous connectivity through social media has provided a buzzword-obsessed generation the opportunity to be made aware of culture-resetting trends faster than ever before, letting these trends run rampant and die all within what feels like a millisecond. Even the queen Barb herself, Nicki Minaj, referred to the popular phrase as “overused social media jargon.”

Some may say that Greta Gerwig’s Barbie epitomized this concept of the cultural reset—extensive marketing, noteworthy celebrity cast, social media frenzy, a track list filled with bops.

But to what degree has the movie and its subsequent “cultural reset” quality soured the disapproving masses through overexposure, and can we trace this back to a very real resentment towards all things girlhood and womanhood? Are Barbie and other heavily marketed “cultural resets” the problem, or is the Barbie backlash just a fundamental attack on girlhood? ...

Following my Barbie movie experience, I vividly remember heading to a nearby outdoor lounge to have food and drinks with some relatives. I had enjoyed the movie and was proud of my fuschia pink outfit, but as my family and I were seated, I quickly realized that there was a clear divide in the room. There were the post-Barbie viewers like myself who were proudly donned in pink from head to toe, and the non-pink wearers who gawked at those of us sporting vibrant hues of pink as if we were a part of some sort of cult. At that moment I couldn’t help but feel judged or even a bit juvenile as I noticed their disapproving eyes, which eventually turned to eyerolls, which eventually turned into laughs, scanning the sea of pink. I felt deep shame and I couldn’t figure out why.

This moment has reeled in my mind for weeks. It even dug out of my subconscious a memory of a ten-year-old, pink-obsessed me, whose parents were about to travel abroad and asked her what clothes she would like them to purchase for her. There was one condition---nothing pink. I specifically remember my dad’s exact words: “We’re done buying pink stuff for you, choose another color.” I was not equipped with the vocabulary to express how ridiculous it was that a harmless color would be banned from my wardrobe, let alone how this revelation made me feel. Was this the mark of the end of my childhood? Why would anyone hate pink??

Color should be for all, without limitations or prejudice. Any qualification that a certain color “belongs” to one gender or another is arbitrary, historically contingent, and embedded in harmful gender hierarchies.

“Would the inescapable marketing activations for the Barbie movie have been as annoying in a color other than pink? There’s no way to know.”

Ignoring and rejecting the color pink’s intrinsic ties to freedom, high spirits, fun, glamor, and grandeur is delusional (and not in a good way), or at least dishonest. Associated with femininity, and especially girlhood, I believe that the color pink skirts the line between delicate and fierce, and it can and should be enjoyed by people of all gender expressions.

As I observed the many gawkers and even received snide jokes from relatives about my pink getup, I had to wonder where this disapproval of the color pink came from. Was it linked to Barbie’s sensationalized marketing schemes that were unavoidable or was this hate just another unconscious stifling and erasure of anything traditionally associated with and enjoyed by young girls and women? With my thinking cap on, I took to Google, and my research showed me the extent to which this single color had been used historically to propagate different agendas across the socialization of children and the enshrining of gender roles in the home and the workplace.

I was fact-checked, and I learned that pink was not always deemed a feminine color. In fact, for hundreds of years the color was seen as akin to red, the color of strength, lust, and vibrancy, and was therefore geared more towards boys, whereas the color blue, assumed to be representative of all things delicate, pure, and light, was associated with girls. Obviously, things shifted later down the timeline and pink became associated with femininity, while blue became the color of masculinity. How did this shift happen? Good marketing.

![]() Image courtesy of the author.

Image courtesy of the author.

Marketing has become a cornerstone of our capitalist society, allowing corporations to sell basically anything to customers through a web of techniques used to persuade and pique interest. This art can be both subtle or pronounced, but when done well, its impact can be felt and seen in the fabric of our society for years. This was the case when gendered items became less optional and more compulsory.

“Pink is for girls, blue is for boys” they said, and it echoed so loudly that it applied to clothes, toys, stationary, accessories, and the list goes on. The idea was, “If we market that this is only for girls, and that is only for boys, chances are we can sell anything in this color to them.” And it worked. This “cultural reset” birthed a new norm, and so allowed for the evolution of various cultural associations to attach to each gendered color. Pink is girly, blue is sporty, pink is vibrant, blue is mellow, pink is too much, blue is just right….

Change is gradual, and we still live in a world where blue is synonymous with male, and pink is synonymous with female. Is this enough to explain why pink is still relegated to second-class status?

While pink is identified with all things “girly,” the color blue, though associated with baby boys, is relatively gender-neutral in most contexts and embraced as, *whispers* just a color. Although the promo run for the Barbie movie and the reaction it elicited both online and off did bring these questions and themes to my mind in a more significant way, I think most women, nonbinary people, and pink-enjoyers on the whole will admit that they have a complicated relationship with the color as it carries a depth of meaning. Sure, we can say that almost anything we wear or attach to ourselves will potentially create perceptions of us by society, but most aren’t as policed or politicized as pink.

We can assume, if we’re being generous to the haters, that the inescapable marketing activations for the Barbie movie were simply annoying. But would they have been deemed annoying if represented by any other color but pink? There’s no way to know.

The Barbie movie spoke to many themes, with one of the most prominent being the constant pressure put on women and the harsh judgements we face. To quote America Ferrera’s famed monologue from the movie, “And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don't even know.” Is a doll that much more different than an intangible color if the reactions and judgment are the same? Where does the real resentment lie?

![]()

Amelyah Roach is a native of Trinidad and Tobago whose passions often oscillate between a love of humanitarian work and a love of fashion. She completed a BA in International Business in Orléans, France and is currently pursuing an M.A. in Luxury, Fashion and Sales Management at the ISM International School of Management in Berlin, Germany. A self-proclaimed overachiever, she speaks three languages and has had professional experiences ranging from communications to supply chain analysis.

As I observed the many gawkers and even received snide jokes from relatives about my pink getup, I had to wonder where this disapproval of the color pink came from. Was it linked to Barbie’s sensationalized marketing schemes that were unavoidable or was this hate just another unconscious stifling and erasure of anything traditionally associated with and enjoyed by young girls and women? With my thinking cap on, I took to Google, and my research showed me the extent to which this single color had been used historically to propagate different agendas across the socialization of children and the enshrining of gender roles in the home and the workplace.

I was fact-checked, and I learned that pink was not always deemed a feminine color. In fact, for hundreds of years the color was seen as akin to red, the color of strength, lust, and vibrancy, and was therefore geared more towards boys, whereas the color blue, assumed to be representative of all things delicate, pure, and light, was associated with girls. Obviously, things shifted later down the timeline and pink became associated with femininity, while blue became the color of masculinity. How did this shift happen? Good marketing.

Image courtesy of the author.

Image courtesy of the author.Marketing has become a cornerstone of our capitalist society, allowing corporations to sell basically anything to customers through a web of techniques used to persuade and pique interest. This art can be both subtle or pronounced, but when done well, its impact can be felt and seen in the fabric of our society for years. This was the case when gendered items became less optional and more compulsory.

“Pink is for girls, blue is for boys” they said, and it echoed so loudly that it applied to clothes, toys, stationary, accessories, and the list goes on. The idea was, “If we market that this is only for girls, and that is only for boys, chances are we can sell anything in this color to them.” And it worked. This “cultural reset” birthed a new norm, and so allowed for the evolution of various cultural associations to attach to each gendered color. Pink is girly, blue is sporty, pink is vibrant, blue is mellow, pink is too much, blue is just right….

Change is gradual, and we still live in a world where blue is synonymous with male, and pink is synonymous with female. Is this enough to explain why pink is still relegated to second-class status?

While pink is identified with all things “girly,” the color blue, though associated with baby boys, is relatively gender-neutral in most contexts and embraced as, *whispers* just a color. Although the promo run for the Barbie movie and the reaction it elicited both online and off did bring these questions and themes to my mind in a more significant way, I think most women, nonbinary people, and pink-enjoyers on the whole will admit that they have a complicated relationship with the color as it carries a depth of meaning. Sure, we can say that almost anything we wear or attach to ourselves will potentially create perceptions of us by society, but most aren’t as policed or politicized as pink.

We can assume, if we’re being generous to the haters, that the inescapable marketing activations for the Barbie movie were simply annoying. But would they have been deemed annoying if represented by any other color but pink? There’s no way to know.

The Barbie movie spoke to many themes, with one of the most prominent being the constant pressure put on women and the harsh judgements we face. To quote America Ferrera’s famed monologue from the movie, “And if all of that is also true for a doll just representing women, then I don't even know.” Is a doll that much more different than an intangible color if the reactions and judgment are the same? Where does the real resentment lie?

Amelyah Roach is a native of Trinidad and Tobago whose passions often oscillate between a love of humanitarian work and a love of fashion. She completed a BA in International Business in Orléans, France and is currently pursuing an M.A. in Luxury, Fashion and Sales Management at the ISM International School of Management in Berlin, Germany. A self-proclaimed overachiever, she speaks three languages and has had professional experiences ranging from communications to supply chain analysis.

Why Barbie Might Be a Lesbian and Barbieland Is a Closet

By Sophie ZiserIf there is one thing missing from the Barbie movie, it is a lesbian storyline. Isn’t making your barbies scissor a canon event? The movie is peppered with pop cultural references, and you don’t have to be queer yourself to see the signs that maybe, just maybe, Barbie is a lesbian?! Below are four signs as to why Barbie might not be as interested in Ken as the Conservatives who hated the movie might hope:

1. The Birkenstocks

This might be the most obvious sign. Much like certain pieces of jewelry, for example thumb rings or just lots of jewelry, tank tops, and Calvin Klein boxers, Birkenstocks are lesbian coded. Even though Birkenstocks are worn by everyone today, they have a history of being THE lesbian clothing item.

2. Closer to Fine

The song 'Closer to Fine,’ which Barbie blasts in her car on the way to the real world, is a lesbian anthem. The Indigo Girls are a lesbian band, famous for their LGBTQ+ activism.

Through her car ride, Barbie escapes the heteronormative Barbieland and embraces her lesbian energy (We all know the feeling of singing in the car alone). Up until:

3. Her reaction when Ken appears in her car

Barbie seems quite shocked when Ken appears on her backseat. She was living in the moment and definitely not expecting him to show up. Despite the fact that anybody would have scared her at that moment, she makes it obvious that she does not want him to join her on her journey.

4. Every night is girls’ night

We all did that: Making your Barbies make out, while the Kens were laying just somewhere else, where they didn’t matter and disturb. I don’t think this needs any more explanation.

5. Weird Barbie is the mother lesbian

Weird Barbie hands Barbie her first pair of Birkenstocks. Her style is ‘crazy butch,’ and she definitely rejects the male gaze. She comprehends the system of Barbieland after being in the real world. The marginalization of queer people in society is shown through her exclusion in Barbieland, because she differs from the other Barbies.

Looking through this lens, one can suggest that Barbie world is Barbie's closet. With her opportunity to enter the real world, a lot of things change—not only her footwear, but also her attitude towards Ken and her whole life. He’s just Ken, but maybe he’s also a beard.

Sophie Ziser is studying Journalism, Cultural Studies and Cultural Anthropology of Textiles

at the Technical University in Dortmund, Germany. But her culture is pop culture. As a typical

confessional member of Gen Z, she writes texts about queer issues in pop culture and on the

internet.

Feelings and Reflections Upon Watching Barbie

By Francesca OsayandeWhen I watched the Barbie movie I felt like a Barbie myself. Growing up, the Barbies I owned were white Barbies but in the movie I saw Barbies that looked like me. I felt beautiful and smart, and for someone who has been through so much, it made me know that no matter what happens I am going to be someone too and I have to keep fighting for myself and people who look like me.

It made my childhood watching this movie, and I realized that as women and girls we must dare to be more, we must fight to be seen and heard, and at the end of the day our voices will matter. We must not give up the fight because we can do so much more in life even when it's hard and it makes no sense.

At the end of the day, women deserve better and we are hardworking and beautiful! And I know I will watch the Barbie movie many times over my lifetime and it will continue to remind me that I can be anything I dare to be.

Francesca Osayande is the founder of Bini Sisters, a company focused on creating inclusivity in the fashion space. She has an AAS in fashion design from Parsons School of Design and a B.A. in public relations and advertising with honors from The University of Tampa.

The Ken Movie

by Diana PortaIn Kendom, everything is perfect and blue. Every morning, Ken wakes up and greets his Ken friends who live around in Mojo Dojo Casa Houses without walls and without stairs. Ken showers every morning with imaginary water, pretends to eat the same waffle for breakfast, and (doesn't) pour from the same carton of milk. He drives along Kendom's main avenue, where we see President Ken, Dad Ken, and other Kens with different professions that every child aspires to become when they grow up. In Kendom, everything is perfect, superficial, and blue. There's no room for serious matters or problems.

One day, Ken wakes up not looking perfect. The water that doesn't come out of the shower is cold. The waffle jumps out of the toaster burnt, and the milk he pretends to drink is expired. Overwhelmed, he turns to Weird Ken, who explains that he has to go to the real world to understand the reason for his situation and to be able to become Stereotypical Ken again. So, he embarks on a long journey that includes stretches by plane, bicycle, camper, and yacht to reach the real world. During this journey, Ken has an outfit for every occasion, and he even discovers that he has a stowaway: Barbie.

In the real world, Ken realizes that nothing is as he thought: kids don't see him as a role model but rather as a toy that has affected their self-esteem by embodying the aesthetic norms of society. The world isn't ruled by men, as in Kendom, but rather women are in control. This is also a revelation for Barbie. For the first time in her life, she understands that she's more than just an accessory to Ken. She likes what she sees and wants to bring that newly discovered lifestyle back to Kendom. So, she leaves Ken behind and returns to Kendom, which she renames "Barbieland," and she teaches everyone this new ideology.

When Ken returns, everything has changed: Kendom is now Barbieland. Barbie has taken over his Mojo Dojo Casa House, and women rule the city. The Kens are subject to the will of the Barbies. They have abandoned their jobs and positions of power to be Barbie’s "long-term, long distance, low commitment, casual boyfriends.”

Distressed, he turns to Weird Ken to help him reverse the situation. Along with other discontinued Kens who are not subject to the matriarchal dynamics, they create a strategy to reconfigure the Kens and restore everything to normal. Their plan: infiltrate these Kens’ daily lives to reason with the other Kens. Gradually, not only is the ideal patriarchal system of Kendom restored, but Barbie believes she is still in control.

Living in this fantasy of having control, the Barbies sing, dance, and worship horses (because they don't really understand what the feminism they profess is about) in a scene that makes them appear ridiculous and naïve to the viewer. Everything Barbie built since taking power—her house, her look, and her protests in the form of musical numbers—is funny, exaggerated, and absurd.

The Kens go further in their fight to regain control and make the Barbies turn against each other. Seeing that her matriarchal world is falling apart, Barbie confesses to Ken that she doesn't really understand feminism and that she has done all of that because she wants to be someone on her own, but she's nobody without Ken.

Ken explains to Barbie that she can be Barbie without Ken, and in the restored patriarchal world of Kendom, some places and job positions are opened up for the Barbies, making it seem like Kendom's society is now more equitable... but is it really?

Having reversed the storyline, we can identify very different feelings from those evoked by the original one. What would your opinion be if the actual movie's story had been this? In the film, women dominate Barbieland, and machismo is the culture that governs the real world. After reading this reversed version of the story, does the original taste the same to you? Or are you confused? I am, too. Because what appears to be a feminist film draws a parallel to the history of women's struggle for their rights (represented by the recently adopted machismo by Ken) in a comedic, unserious, and even misunderstood way by the protagonists themselves, leaving the viewer to laugh at it.

Let's briefly recall how this was our history. Most societies have followed a patriarchal scheme in which gender has been divided into men and women, and along with this, roles have been assigned to each one in which men are dedicated to public life, economic affairs and politics, and are the decision makers shaping the community and the family, while women are responsible for the house, education, and the creation and provision of basic needs (which are considered, erroneously, to be less important than the tasks in the public sphere). One of the fundamental problems of this social dynamic is the lack of access to education for women, the null possibility of choosing a path other than that marked by their gender, and the denial of active participation in the society of which they form an essential part and that evolves while their role remains static in history. This is not a problem just for women. The omission of women from intellectual society implies an uneven cognitive evolution and created a significant delay in progress, like walking on one foot. This was realized, for example, by merchants who found that once women had "permission" to go shopping, the market (and with it, the economy) expanded like never before. The same thing happened in the fields of art, science, literature, etc. This inequality is a problem for men as well, who, as Ken sings (in the non-gender-reversed version of the movie), don't seem to have the right to show their feelings, nor can they consider taking up housework.

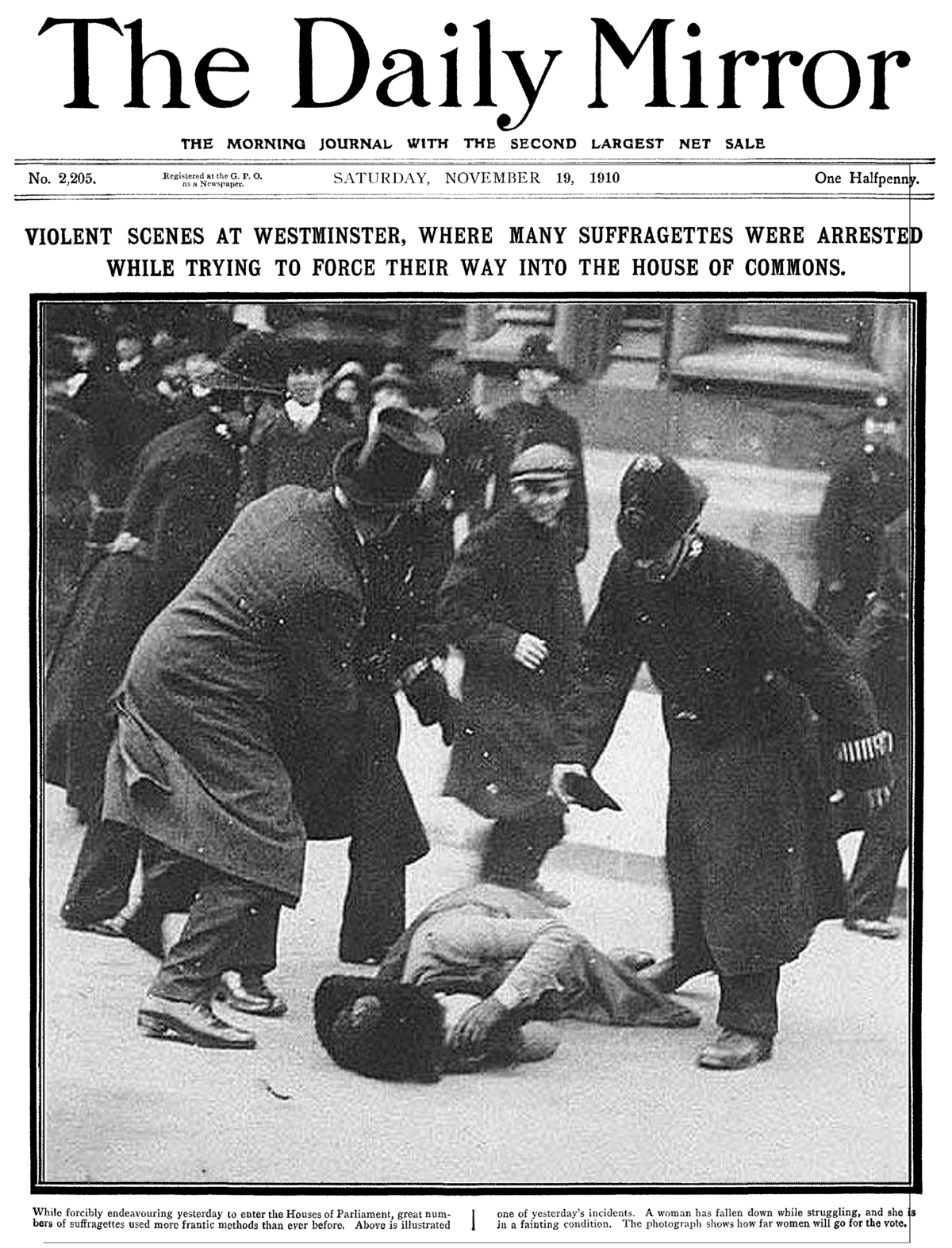

After many years and vain attempts to change the social position of women and peacefully request the same rights as men, at the beginning of the 20th century the Women's Social and Political Union, created by Emmeline Pankhurst, launched a campaign of bold and aggressive action. The bastions of male dominance came under attack: churches were torched, store windows smashed, politicians' homes bombed—in the same way that Ken raged at Barbie's dream house. But public sympathy faltered. The politicians and press considered the violence unfeminine and unrepresentative. The suffragettes began to be ridiculed. Posters appeared showing hapless husbands trying to cook and care for children who had been abandoned by their protesting mothers. There were numerous cartoons of women attacking the police with umbrellas or rolling pins. Among the merchandise were satirical toys, including a jack-in-the-box featuring a suffragette caricatured as a witch leaping free from a prison cell with a women's rights banner in her hand.

The suffragettes needed to find more effective and attractive means of protest in order to gain the respect and support of the people. They held rallies between 1907 and 1913, with women representing all walks of life: Artists, surgeons, scientists, store clerks, writers, waitresses, actresses, musicians, academics, and gymnasts (as many as Barbie models exist). The rallies functioned as showcases of women's capacity and as shows of female solidarity. Her aim was to counter the charge that the suffrage campaign was a mere diversion for the idle middle and upper classes, perpetrated by women with intellectual pretensions. In the Barbie movie, it is Ken who organizes these rallies, accompanied by a song, in the same way that these rallies had hymns like “The March of the Women” by composer Ethel Smith.

Seeing clearly the parallels between the Barbie movie and the history of feminism, we have to ask:

Is Barbie a feminist movie? The film imagines a world turned upside down, prompting the viewer to make fun of the patriarchy, but is it really funny? Let's imagine for a moment that our world was like this and that today we had to fight to tear down matriarchy in favor of a more equal society... would Barbie be a comedy? Would men find it funny if they enacted the fight they have waged for centuries for their rights… with toy horses? Many may object that our history is not like that, and that, if it were the contrary, it would not be the same, but in any case, is discrediting a movement the solution for a better society? For the restoration of order as we know it? Is matriarchy better than patriarchy? Is the power struggle the path to equality? And, in the event that history was reversed and we lived from now on in a matriarchal society... why would it be better? Is it better to walk with only the left foot instead of the right, but still with only one foot?... and what happens to the other genders that do not appear on either of the two sides?

Another question is: why does the film insinuate that in the world of women everything is perfect, pink, naïve, and unaware of reality? Why doesn't it look like the real world? The latter can be explained from the perspective that, in the end, it is the story of a doll and how we played with it, pretending that it ate, bathed, and moved with imaginary inputs. But is the movie just about the life of a doll? How much can we pretend that comedy isn’t being made of something serious? Is it the movie, not Barbie, that sets feminism back 50 years?

Diana Porta is a fashion designer and researcher in fashion studies. She sees fashion as a cultural asset through which social issues such as colonialism

and racism can be addressed. She hosts the podcast in Spanish “Historia y moda” that analyses society, economy, politics, and gender roles through fashion.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics