Images courtesy of the authors.

Images courtesy of the authors.

Sara Chong Kwan is senior lecturer in Cultural and Historical Studies at London College of Fashion, University of the Arts London. Her teaching, research, and scholarly writing explores sensory and embodied dimensions of fashion, with a focus on everyday lived experience and sensory research methods. She is Sensory Design Reviews Editor for The Senses and Society Journal. Author photo by Antony Crolla https://antonycrolla.format.com/

Cian O’Donovan is Senior Research Fellow at the UCL Department of Science and Technology Studies. Cian researches the impacts of digital transformation on public infrastructures for housing and social care. He uses this work to question the relationship between innovation and democracy, asking questions like who benefits from innovation, who pays for innovation, and who decides?

Luke Stevens is the co-founder and designer of RANRA_Studio. The studio engages in multifaceted projects operating at a range of scales from textile development and product design to knowledge production and systems-level interventions. These projects act as a space for poetic yet pragmatic experimentation that challenges existing industry practices and continually questions how and why something is made.

Olivia Hegarty is Senior Lecturer in Creative Pattern Cutting at London College of Fashion, UAL. Olivia teaches on the MA Fashion Design Technology Womenswear course at LCF. She has experience teaching internationally and advising on curriculum design in higher education. Olivia’s decolonial research explores the idea and practice of ‘fit’ in fashion making and education, by centring bodily ways of knowing and situated knowledges.

A full PDF version of this visual essay is available here.

We propose here an alternative method for teaching ‘garment fit’ within fashion design education: The Critical Fitting. This workshop method has been developed through ongoing practice-based research. This project contributes to a growing body of work within fashion design pedagogy that critiques the “dominant assumptions of Eurocentric fashion epistemologies” embedded in the technical practices, skills, and tools currently taught to fashion design students. [1] Our own experience as educators (teaching design, patterncutting, fashion studies, and science and technology studies) informs the development of these workshops. To date, iterations of the workshop have been run at a number of global fashion and science and technology studies conferences, with London College of Fashion students and educators (as standalone workshops and embedded within the students’ design and technical units). We have also run the workshop in collaboration with other fashion schools. In line with many other fashion educators who are “building communities of resistance” through radical and speculative teaching methods, the creativity of the fashion school, or rather its educators and students, provides us with an opportunity to “destabilise the self-reinforcing power structures of the twenty-first century fashion industry.” [2]

Established methods of teaching ‘Fit’: power and erasure

At London College of Fashion, as is the case globally in fashion education settings, students learn established industry practices of design and making within their technical design units and briefs. These skills and techniques uphold industry ‘standards’ and enable them to apply for jobs in the sector on graduation. Established methods of flat patterncutting (based on western archetypal garments and blocks or slopers) are core learning outcomes alongside techniques of fitting that build fixed forms into garments through shaped seams and darts. The default convention is to teach how to fit standard body sizes or mannequins and adjust a design’s flat pattern accordingly, ready for size-grading on a production line.

In conventional fitting ‘crits,’ students learn how to fit without reflection on the values embedded in the process. In uncritically teaching these practices, assumptions around how a garment should be constructed and worn on the body, methods of fitting to the body, what makes a ‘good’ fit, and who decides what is a good fit are reproduced and embedded as universal, normative, and ideal.

These practices of fitting, in promoting established industrial and Eurocentric production techniques, exclude fitting practices that are intuitively learned. In replicating industrial practices in education, we risk erasure of tacit knowledge of fitting fabric to our bodies, as seen in pre-industrial garment types and non-western dressing practices such as the sari, lungi, or wrapper. Indeed, when students of those diverse global backgrounds are present in the classroom, their own lived experience is relegated through fitting practices that embed colonial relations by hierarchically valuing industrial tools over hands. In this way, enforcing standard practice and pedagogy in the classroom estranges students from their very own cultural and embodied sensory memories and knowledges. This contributes to what Seremetakis characterizes as a “disorienting penetration of metropolitan modernity.” [3] It flattens cultures and erases difference across all walks of life.

![]()

The Critical Fitting

One of the assumptions unpicked by the critical fitting is that fitting practices should aim towards a fixed fitted garment at all. While a conventional fitting takes place on a body, the model is passive while designer and technicians fit to their form. The wearer’s sensory needs and desires are devalued, alongside their own embodied and sensory skills in fitting garments to their body.

The critical fitting presents an un-doing of current teaching practices by re-configuring ‘fit’ as an open-ended process, explored through the active and collaborative ‘doing of fit’ combined with discursive reflection and storytelling. Rather than teaching fit as a set of skills for a fixed, standardized outcome, the workshop space is designed, following Freire, to facilitate a transformative and liberatory journey for participants, alongside collaborative knowledge production. [4] Participants are encouraged to explore their own and others’ embodied tacit memory and sensory skills of fitting garments to the body, to use their hands as well as tools, to question preconceived ideas of what makes a ‘good’ fit, and to pay attention to each other and the relationship between bodies and materials in the process.

In focusing on the sensory experience of the wearer, we predicate situated knowledges and pluriversal approaches to knowledge. [5, 6] This encourages us as educators to meet students in their own worlds of reference, aligning decolonial pedagogy that assumes the co-existence of many ‘worlds’ with critical pedagogy that centers the empowerment of students through critical reflection on the value of their lived experience. [7, 8] By placing value on the worlds that students bring with them into the classroom, we “shift the geography of reason.” [9]

Key Objectives for the Critical Fitting Workshop design

Established methods of teaching ‘Fit’: power and erasure

At London College of Fashion, as is the case globally in fashion education settings, students learn established industry practices of design and making within their technical design units and briefs. These skills and techniques uphold industry ‘standards’ and enable them to apply for jobs in the sector on graduation. Established methods of flat patterncutting (based on western archetypal garments and blocks or slopers) are core learning outcomes alongside techniques of fitting that build fixed forms into garments through shaped seams and darts. The default convention is to teach how to fit standard body sizes or mannequins and adjust a design’s flat pattern accordingly, ready for size-grading on a production line.

In conventional fitting ‘crits,’ students learn how to fit without reflection on the values embedded in the process. In uncritically teaching these practices, assumptions around how a garment should be constructed and worn on the body, methods of fitting to the body, what makes a ‘good’ fit, and who decides what is a good fit are reproduced and embedded as universal, normative, and ideal.

These practices of fitting, in promoting established industrial and Eurocentric production techniques, exclude fitting practices that are intuitively learned. In replicating industrial practices in education, we risk erasure of tacit knowledge of fitting fabric to our bodies, as seen in pre-industrial garment types and non-western dressing practices such as the sari, lungi, or wrapper. Indeed, when students of those diverse global backgrounds are present in the classroom, their own lived experience is relegated through fitting practices that embed colonial relations by hierarchically valuing industrial tools over hands. In this way, enforcing standard practice and pedagogy in the classroom estranges students from their very own cultural and embodied sensory memories and knowledges. This contributes to what Seremetakis characterizes as a “disorienting penetration of metropolitan modernity.” [3] It flattens cultures and erases difference across all walks of life.

The Critical Fitting

One of the assumptions unpicked by the critical fitting is that fitting practices should aim towards a fixed fitted garment at all. While a conventional fitting takes place on a body, the model is passive while designer and technicians fit to their form. The wearer’s sensory needs and desires are devalued, alongside their own embodied and sensory skills in fitting garments to their body.

The critical fitting presents an un-doing of current teaching practices by re-configuring ‘fit’ as an open-ended process, explored through the active and collaborative ‘doing of fit’ combined with discursive reflection and storytelling. Rather than teaching fit as a set of skills for a fixed, standardized outcome, the workshop space is designed, following Freire, to facilitate a transformative and liberatory journey for participants, alongside collaborative knowledge production. [4] Participants are encouraged to explore their own and others’ embodied tacit memory and sensory skills of fitting garments to the body, to use their hands as well as tools, to question preconceived ideas of what makes a ‘good’ fit, and to pay attention to each other and the relationship between bodies and materials in the process.

In focusing on the sensory experience of the wearer, we predicate situated knowledges and pluriversal approaches to knowledge. [5, 6] This encourages us as educators to meet students in their own worlds of reference, aligning decolonial pedagogy that assumes the co-existence of many ‘worlds’ with critical pedagogy that centers the empowerment of students through critical reflection on the value of their lived experience. [7, 8] By placing value on the worlds that students bring with them into the classroom, we “shift the geography of reason.” [9]

Key Objectives for the Critical Fitting Workshop design

- Critique existing design tools and techniques

-

Center the wearer in the fit process

- Explore lived experience and embodied sensory knowledge and skills of fitting

- Stimulate critical discussion of broader issues around colonial modernity, the fashion industry, fashion pedagogy, and the participants’ relationship to these contexts

“In replicating industrial practices in education, we risk erasure of tacit knowledge of fitting fabric to our bodies, as seen in pre-industrial garment types and non-western dressing practices such as the sari, lungi, or wrapper.”

Rationale for the Critical Fitting

Colonial practices of extraction, exclusion, assumption of superiority, and control of imaginaries are embedded in fashion education’s entanglement with fashion production systems. [10] Theoretical, cultural, and historical research within fashion studies is working hard to address Eurocentric hegemony and the global inequalities of the fashion system from a decolonial perspective, and this informs the teaching of critical inquiry to students. However, it is only very recently that fashion theorists, practitioners, and educators have begun to critique the exclusionary values embedded within technical design practices and curricula, and to explore radical alternatives to the normal “‘operating procedures’ of the fashion industry.” [11] In particular, the work of Tanveer Ahmed has been central in opening up the design practices, skills, tools, and equipment commonly taught at global fashion schools to decolonial critique and pluriversal re-imagining. [12]

There is an urgent need for fashion educators to work collaboratively with students to materially, as well as theoretically, challenge the “damaging political, social and environmental effects” of the industrial fashion system. [13] Today, students are encouraged within the curricula to be creative and critical thinkers, to disrupt established norms through their design work, and to consider the ethics of the fashion system. The next step concerns how we teach students design and making skills, i.e., the methods and tools that students are required to learn in order to ‘fit’ into industry, and how these also need to come under scrutiny. As Stevenson points out, this tension between radical and critical values and the unequal and destructive fashion system which fashion schools feed presents a specific challenge to us as fashion educators: “How do we drive institutional critique of the very system we are training our students to enter?” [14]

The critical fitting aims to encourage educators and students to reflect on this tension from their own positionalities and question who and what knowledges are excluded when fashion education is made to fit into the measuring and standardizing practices of industry. There is an uncomfortable tension in confronting established technologies, as it requires educators to reflect upon the value of their own skill set and professional expertise, the position of authority that this gives them in the classroom, and the ideologies they embed.

A society’s knowledge and skill set resides, as Juhani Pallasmaa articulates in The Thinking Hand, “directly in the senses and muscles, in the knowing hands and intelligent hands” of their members. [15] In the demonstrative teaching of garment fit, “Learning a skill is not primarily founded on verbal teaching but rather on the transference of the skill from the muscles of the teacher directly to the muscles of the apprentice through the act of sensory perception and bodily mimesis.” [15] The critical fitting, rather than demonstrating and fixing a ‘right’ way to do fit, encourages participants to pay close attention to the multiple embodied “realities of the task in question.” [16] Participants use their senses and ‘thinking hands’ to explore the constraints and resistances of established techniques, opening them up to a critical process of ‘undoing’ and ‘redoing’. The workshop space is configured as one of uncertainty but also trust, where playful explorations are “carried out with perceptive senses and a receptive empathetic heart.” [17] enabling those sticky and uncomfortable feelings to be confronted collaboratively and with care.

Workshop Guidelines

Settings: Room with floor space or moveable tables, option to move outside.

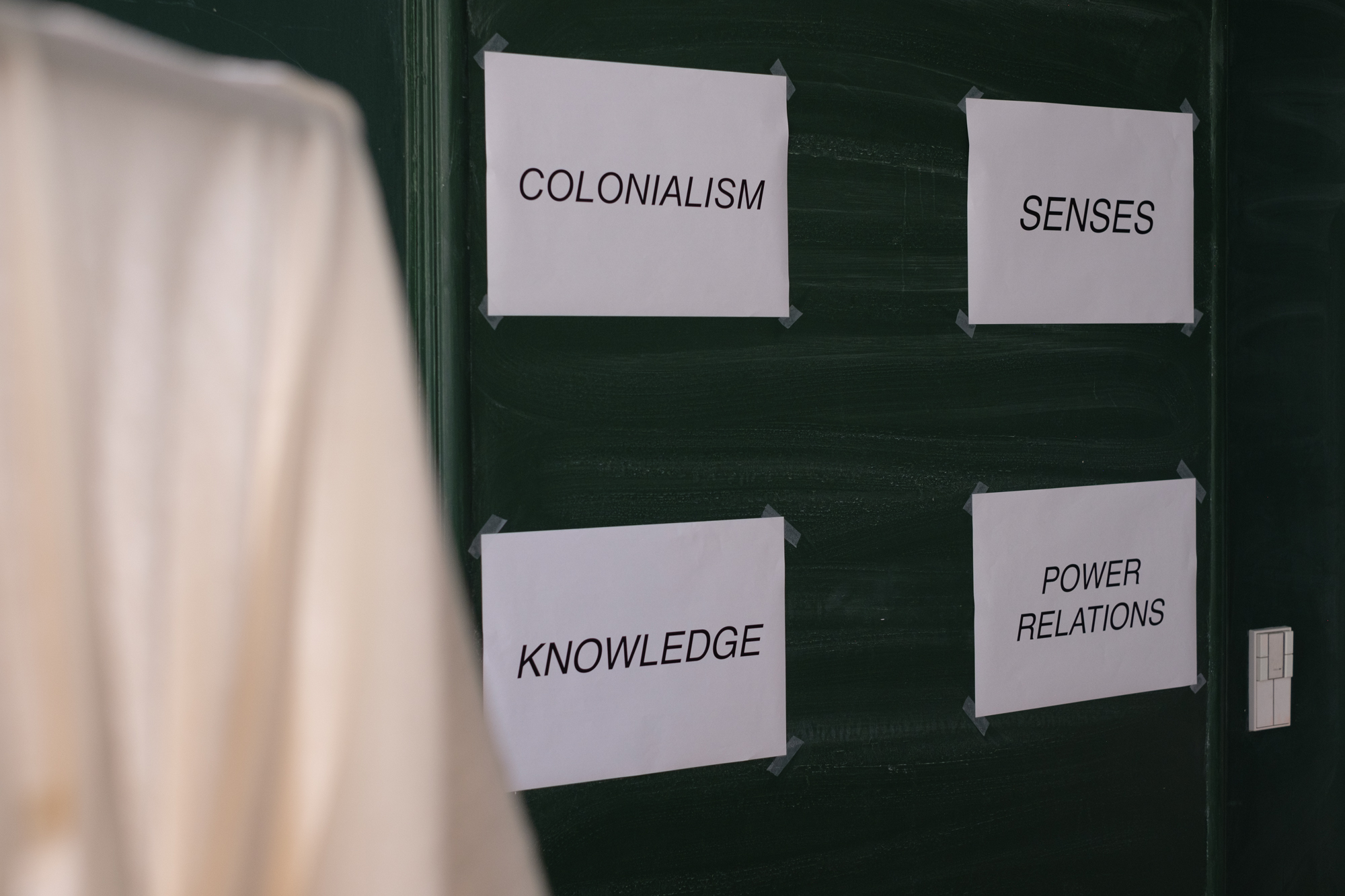

Participant groups: Participants are divided into 4 groups with at least 2 participants in each group. Each group is assigned one of the following ‘themes’: Senses, Colonialism, Knowledge, or Power Relations (Fig. 4). The themes broadly reflect core theoretical concerns of the project.

Facilitator: Ideally one facilitator per group

Resources for each group:

- A set of prompt cards related to their theme (Fig. 6). The prompts include a series of fitting and wearing ‘actions’ with follow up questions.

-

A pouch with a set of drawing and fitting tools: markers, tailor’s chalk, snips, safety pins, bulldog clips (Fig. 5).

-

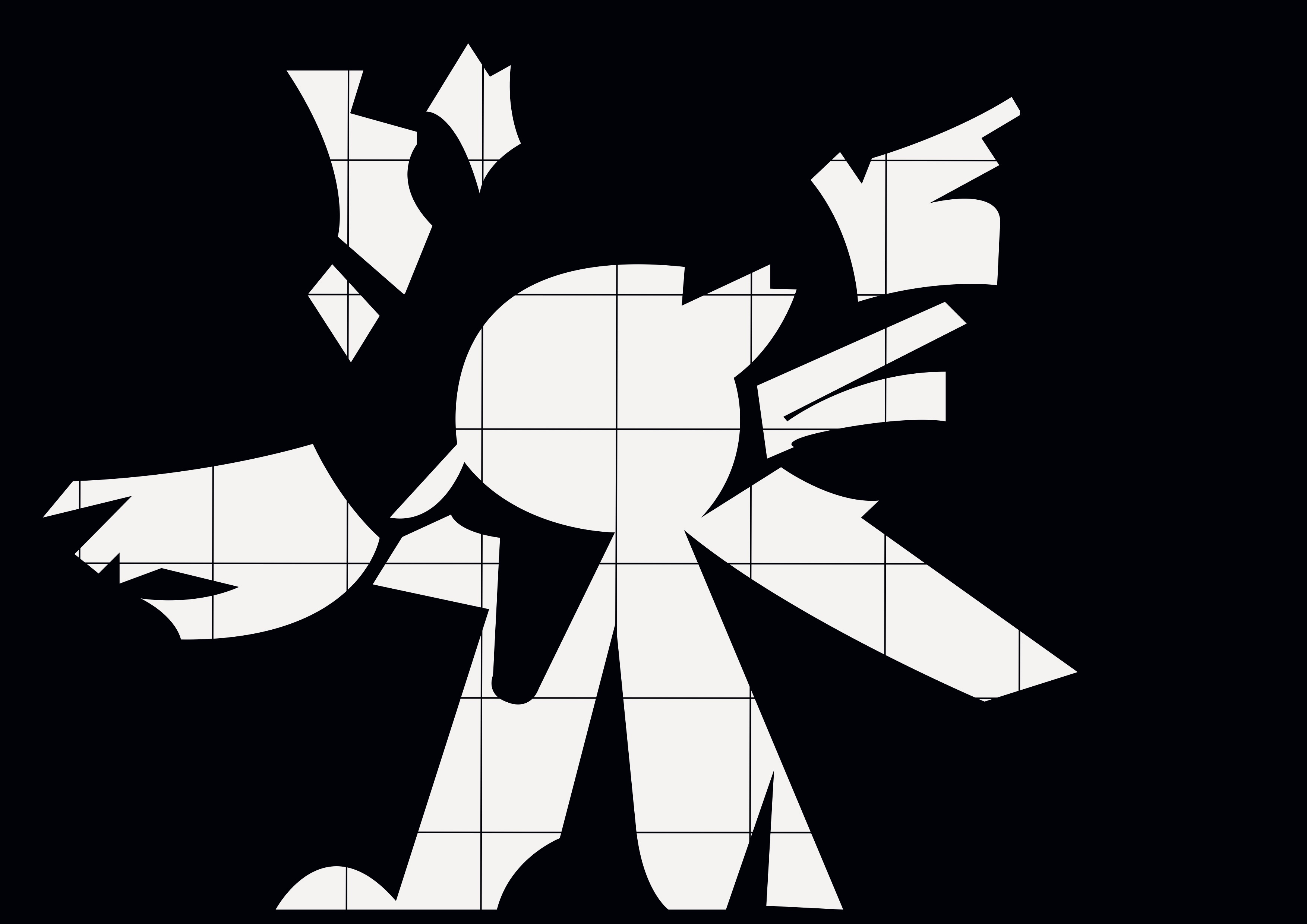

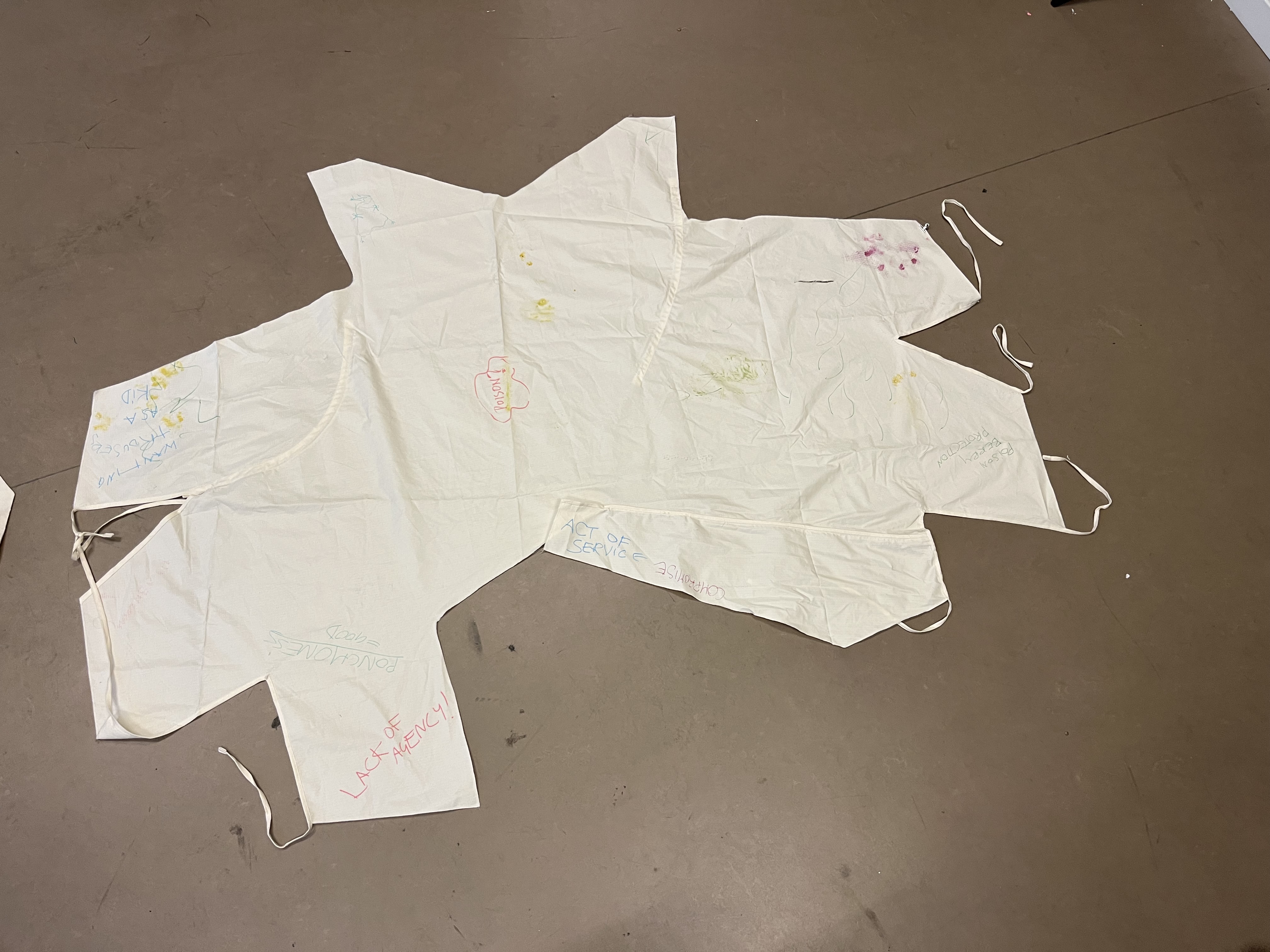

An abstract garment or toile. The garment can be made by students in a previous session - the output of an experimental pattern cutting activity for example, or provided by the facilitators. It is designed to be a non-definable garment, open-to-interpretation but with some suggestion of archetypal detail so that it can be read as a ‘garment.’ The main requirement is that it should have multiple possibilities for fitting rather than a fixed, predetermined wearing mode (Fig. 10 is an example of a garment made for one of the workshops).

Actions:

- The group responds to the prompt cards in any order they choose.

-

In response to the action on the card, each group fits the abstract garment to themselves or colleagues (over their clothing).

-

Each action is followed by reflection and discussion responding to the questions on the card.

-

The group records their discussion as mark-making directly on the abstract garment.

Final reflection and evaluation:

Participants and facilitators come together to share their marked-up garments, experience, and thoughts.

Call to Action

Through playful but conceptually powerful strategies, such as the critical fitting workshop, we can re-ignite sensory and embodied knowledge. These transformative pedagogies can build skills and capabilities in unpicking dominant narratives on the relations between fashion industry and education making space for students and educators to imagine - and hopefully go on to build - other modes of fashion practice. We hope that the critical fitting workshop guidelines outlined here will encourage other fashion educators to make critical interventions within their own teaching of ‘fit.’ We warmly invite requests for further guidance or assistance with this.

Notes: Fit But You Know It

[1] T. Ahmed. “What is education in fashion? Reflecting on the coloniality of design techniques in the fashion design educational process,” International Journal of Fashion Studies, 9, no. 2, p: 401, (2022).

[2] L. Gardner, and D. Mohajer va Pesaran (Eds). Radical Fashion Exercises: A Workbook of Modes and Methods (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2023).

[3] C.N. Seremetakis (Ed). The Senses Still: Perception and Memory as Material Culture in Modernity (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1996): 9.

[4] P. Freire. Teachers as Cultural Workers: Letters to Those Who Dare Teach, Expanded ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 2005).

[5] Donna Haraway. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 575–99, (1988). https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

[6] A. Escobar. Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds. (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018).

[7] P. Freire. Pedagogy of the Oppressed (M. Bergman Ramos, trans.) New York London New Delhi Sydney: Penguin Books, 2017.

[8] bell hooks. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. (New York London: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, 1994).

[9] W.D. Mignolo. “Epistemic disobedience, independent thought and decolonial freedom,” Theory, Culture & Society, 26(7–8), pp: 159–181, (2009). https://doi. org/10.1177/0263276409349275.

[10] S. Arora, and A. Stirling. “Colonial modernity and sustainability transitions: A conceptualisation in six dimensions,” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 48, p: 10073, (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eist.2023.100733.

[11] L. Gardner and D. Mohajer va Pesaran, Radical Fashion Exercises, p:13.

[12] T. Ahmed, “What is education in fashion?”, p. 402.

[13] Caroline Stevenson, “Radical pedagogies: Right here, right now!,” Fashion Theory, 26:4, 465-473 (2022): 466.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Juhani Pallasma. The Thinking Hand: Existential and Embodied Wisdom in Architecture. (Wiley, 2009): 15.

[16] Pallasma, The Thinking Hand, 113.

[17] Pallasma, The Thinking Hand, 147.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics