Vittorio Linfante is an art director, textile designer, and docent in fashion design, branding, and communication at the Politecnico di Milano, Università di Bologna and NABA. He curated the Il Nuovo Vocabolario della Moda Italiana exhibition at the Triennale di Milano 2015. He authorises articles and books on the ties between fashion, art, and communication, such as Catwalks, Le sfilate di moda dalle Pandora al digitale (2022), and he has co-authored Italian Textile Design. From Art Deco to the Contemporary (2023) with Massimo Zanella.

“Fashion is politics. Fashion is desire.”; “Choosing a dress means expressing an opinion.” These are among the statements included in the creative manifesto of Maria Grazia Chiuri, creative director of Dior, — statements that, season after season, the Italian designer also materializes through her fashion shows. Quotes from Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Linda Nochlin, Robin Morgan, and Yael Bartana (“We all should be feminists!” “When women strike, the world stops”, “What if Women Ruled the World?”, “Sisterhood Is Global”, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”) have guided Chiuri’s creative process at Dior since she became creative director in 2017. In her creative vision, catwalks become performative spaces to stage not only products but also her political views. Additionally, thanks to new technologies, fashion shows have become an essential channel for conveying a specific thought or opinion, or for stimulating debate.

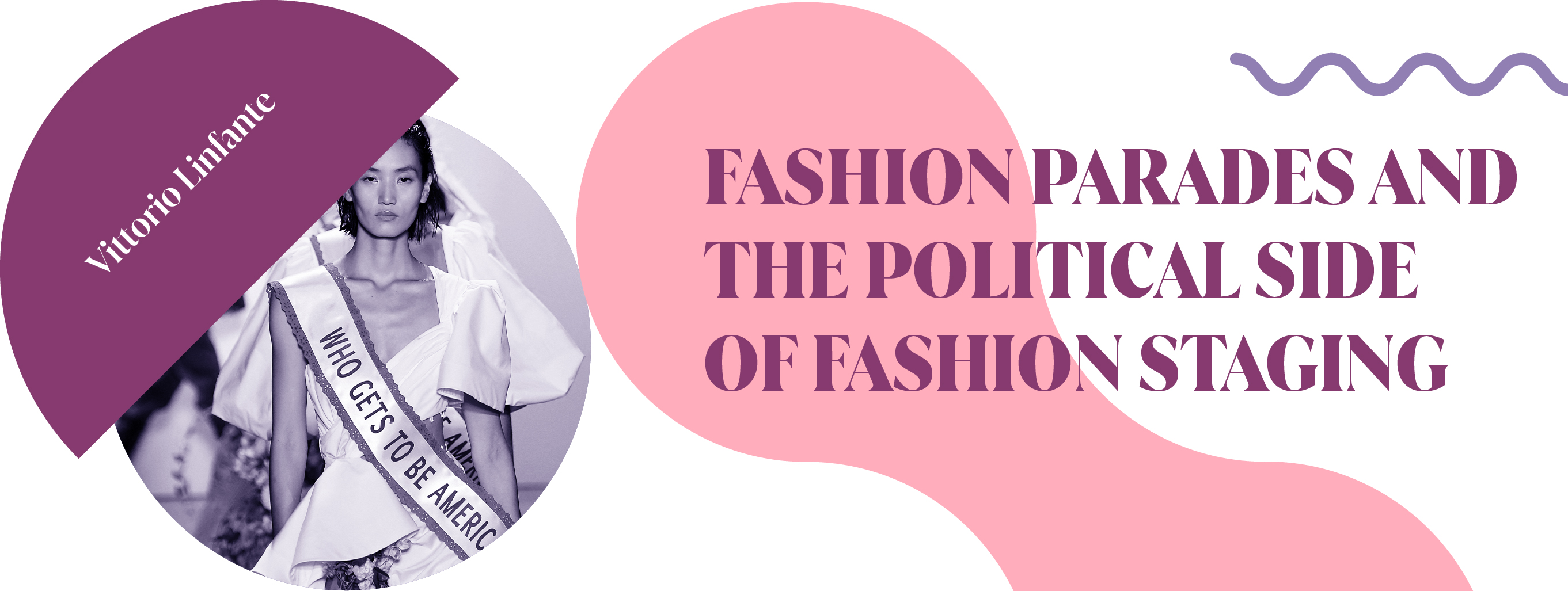

Historically, fashion shows played a political role capable of defining different forms of staging the passage of time. The history of fashion is paved with such examples, from the rupture with the past done by Walter Albini, Caumont, Ken Scott, Krizia, Missoni, and Trell, when they left Florence in 1971 to open a new fashion path in Milan, to Moschino who, in 1990 stated (clearly and through a theatrical staging) “Stop the Fashion System;”. More recently, Serpica Naro’s fashion show in 2005, Katharine Hamnett's position against the war in Iraq in 2003, and Vivienne Westwood who, in 2008, drew attention to the situation at Guantanamo Bay. And again, Sid Bryan and Cozette McCreery (designer of Sibling), who took stands against Brexit, the many expressions of support to the Ukrainian people staged during the February and March 2022 fashion shows, the desire to revolutionize, or even destroy, the fashion system expressed by Demna Gvasalia through his fashion shows for Vetements, the breaking of gender and beauty stereotypes by means of street casting (a tool increasingly used by various brands), and the works of LRS (Pic. 01) and Prabal Gurung (Pic. 02), who uses clothes as surfaces to share political statements while clothes themselves become a form of protest.

This article aims to investigate, from a historical perspective, the current political role of fashion shows as performative acts, created to present new products and trends as well as to stimulate debate. These performances, also thanks to social media, can convey the different messages that fashion is increasingly trying to promote, both through its products and through its catwalk shows. In this sense, fashion shows are a tool both for presenting new seasonal products and for conveying political and social messages.

Historically, fashion shows played a political role capable of defining different forms of staging the passage of time. The history of fashion is paved with such examples, from the rupture with the past done by Walter Albini, Caumont, Ken Scott, Krizia, Missoni, and Trell, when they left Florence in 1971 to open a new fashion path in Milan, to Moschino who, in 1990 stated (clearly and through a theatrical staging) “Stop the Fashion System;”. More recently, Serpica Naro’s fashion show in 2005, Katharine Hamnett's position against the war in Iraq in 2003, and Vivienne Westwood who, in 2008, drew attention to the situation at Guantanamo Bay. And again, Sid Bryan and Cozette McCreery (designer of Sibling), who took stands against Brexit, the many expressions of support to the Ukrainian people staged during the February and March 2022 fashion shows, the desire to revolutionize, or even destroy, the fashion system expressed by Demna Gvasalia through his fashion shows for Vetements, the breaking of gender and beauty stereotypes by means of street casting (a tool increasingly used by various brands), and the works of LRS (Pic. 01) and Prabal Gurung (Pic. 02), who uses clothes as surfaces to share political statements while clothes themselves become a form of protest.

This article aims to investigate, from a historical perspective, the current political role of fashion shows as performative acts, created to present new products and trends as well as to stimulate debate. These performances, also thanks to social media, can convey the different messages that fashion is increasingly trying to promote, both through its products and through its catwalk shows. In this sense, fashion shows are a tool both for presenting new seasonal products and for conveying political and social messages.

Motto printed on underwear during the LRS New York presentation on Februar 10, 2017 in New York. Photo © Jason Kempin/2017 Getty Images

Motto printed on underwear during the LRS New York presentation on Februar 10, 2017 in New York. Photo © Jason Kempin/2017 Getty ImagesThe language of fashion, as defined by Barthes, [1] can multiply the value of the artifacts it produces, the associated narratives, and their staging which incorporates different elements: aesthetic, semantic, expressive, communicative, emotional and political content. [2]

Following Harold H. Saunders, who assumes that “politics is about relationships, [3] let us start from the assumption that fashion, as an instrument of interpersonal communication, is political. We can thereby consider fashion, and its staging through fashion shows, as having a political relevance as it affects the relationships between people. In this context, clothing, fashion, and staging all imply an intersubjective social world in which one presents oneself and is seen by others. [4] Fashion and fashion staging increasingly represent a complex design field that transcends the production of merely wearable products. It consolidates itself as a design field capable of generating hybrid goods that, by their very nature, have an interpersonal, social and increasingly political communicative function. [5] [6]

Fashion is understood here as a complex system of objects and meanings, increasing its value depending on who makes, uses, and wears the clothes — an essential concept that sometimes defines and sometimes adapts to the changes of taste and style, and is both social and political. Not only art and politics, but also fashion can be understood, following Rancière’s thought, as a form of knowledge capable of constructing “fiction,” that is, material rearrangements of signs and images between what is seen and what is said, between what is done and what could be done.” [7]

Fashion is, by its nature, an interpreter and mirror of social changes that, as Eleonora Fiorani states, unites and stitches together what would apparently seem irreconcilable: tradition and modernity, past and future, localism and globalization, social inadequacy and consumerism. [8] Fashion, in this sense, can indicate “how people in different eras have perceived their position in social structures and negotiated status boundaries.” [9] As Andrew Bolton states: “fashion functions as a mirror to our times, so it is inherently political. It’s been used to express patriotic, nationalistic and propagandistic tendencies, and complex issues related to class, race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality.” [10]

Following Harold H. Saunders, who assumes that “politics is about relationships, [3] let us start from the assumption that fashion, as an instrument of interpersonal communication, is political. We can thereby consider fashion, and its staging through fashion shows, as having a political relevance as it affects the relationships between people. In this context, clothing, fashion, and staging all imply an intersubjective social world in which one presents oneself and is seen by others. [4] Fashion and fashion staging increasingly represent a complex design field that transcends the production of merely wearable products. It consolidates itself as a design field capable of generating hybrid goods that, by their very nature, have an interpersonal, social and increasingly political communicative function. [5] [6]

Fashion is understood here as a complex system of objects and meanings, increasing its value depending on who makes, uses, and wears the clothes — an essential concept that sometimes defines and sometimes adapts to the changes of taste and style, and is both social and political. Not only art and politics, but also fashion can be understood, following Rancière’s thought, as a form of knowledge capable of constructing “fiction,” that is, material rearrangements of signs and images between what is seen and what is said, between what is done and what could be done.” [7]

Fashion is, by its nature, an interpreter and mirror of social changes that, as Eleonora Fiorani states, unites and stitches together what would apparently seem irreconcilable: tradition and modernity, past and future, localism and globalization, social inadequacy and consumerism. [8] Fashion, in this sense, can indicate “how people in different eras have perceived their position in social structures and negotiated status boundaries.” [9] As Andrew Bolton states: “fashion functions as a mirror to our times, so it is inherently political. It’s been used to express patriotic, nationalistic and propagandistic tendencies, and complex issues related to class, race, ethnicity, gender and sexuality.” [10]

Nepalese-born fashion designer Prabal Gurung, reflecting on the glowing debat over immigration into the United States during the final runway show of his spring/summer 2020 collection, presented models of different origins with a sash similar to those used to crown Miss America with the motto "Who should be an American?"

Photo © Mike Coppola/Getty Images for NYFW: The Shows/2019 Getty Images

“If a thought needs words, fashion needs bodies. Fashion as a language dresses the body with meanings, becoming an expression of personal and social identity; therefore, to wear is to communicate.”

Fashion, as a communicative interface concerning primarily the human body, as a production system, and as an economic and political agent, increasingly contributes to defining new forms of staging that not only speak of clothes and bodies, but also of our present thus creating the narrative behind a collection, i.e., the fashion show, interpretable as a form of manifesto and political statement.

The pervasiveness of digital media since the early 2000s has redefined the fashion show, its rituals, and its dynamics, opening up more and more to the general public and transforming it from a presentation for the few to an event, from a show limited in space and time to a true palimpsest that not only shows products but also expands into artistic, performative, musical, and cinematic forms.

In this context, fashion shows represent one of the fundamental tópoi of the fashion system: the first showcase, the most important way to present and stage the collections, the ideas, and the style of a brand, effectively and immediately communicating the product and its entire design path.

Fashion shows, for which the dichotomy between packaging and product is disintegrating, thus become the focus of what Orvar Löfgren calls today’s catwalk economy, that is the need to communicate an increasingly appealing image blending innovation and creativity: a commercial artistic performance, where tickets are free but almost everything on the stage is for sale,[13] designed to succeed in engaging an ever-growing audience (in situ and online) and thus establish a visual, but above all emotional, relationship between designers/brands/models acting on the catwalk and the audience. [11] [12][13]

Alongside the creation of a multifaceted abacus of staging possibilities, over the years, there has been an increasingly rapid expansion of the geographical boundaries within which the current fashion system and design circles have moved, increasingly involving digital technologies and media. The voyeuristic nature of fashion shows, amplified by fruition through social media, has contributed to their consolidation as practical communication tools. Perpetuating modes that have been established for more than a century, the catwalk still represents an eagerly awaited moment, during which the novelty of products is associated with the constant research of forms of representation, spaces, and sharing. It is precisely this solid communicative value, as well as the increasing pervasiveness of messages through digital channels, that have meant that fashion communication is not only limited to sharing new aesthetics and new forms of dress, but also real political messages and decisive stances.

As a catalyst of transformations and changes, in its continuous mutations, fashion has evolved from an elite to a mass commercial phenomenon, from a production system to a communication system, increasingly in the service of spontaneous political actions. [14] Thanks to the explosion of social media, fashion shows now represent an independent and trans-disciplinary design field, in which architecture, set design, dramaturgy, performing arts, communication, and new technologies are intertwined.

The entire fashion system can be said to be enclosed between the extremes of a structure that on the one hand contemplates the artistic/creative dimension reserved to insiders and, on the other, addresses the expressive/communicative one to the public. In the fashion system, the artist’s creative impulse is expressed through the use of the multiple languages of contemporary communication, from photography to advertising, from design to fashion imagery and fashion shows, from theater and opera to cinema, radio, and television. The line between fashion culture and fashion marketing is fragile. [15]

The product presented during a fashion show, the choice of a stage, space, or city, and the definition of a precise communication strategy, all become ways for fashion to share not only a creative and productive process but, increasingly, to explicitly communicate clear political statements.

The pervasiveness of digital media since the early 2000s has redefined the fashion show, its rituals, and its dynamics, opening up more and more to the general public and transforming it from a presentation for the few to an event, from a show limited in space and time to a true palimpsest that not only shows products but also expands into artistic, performative, musical, and cinematic forms.

In this context, fashion shows represent one of the fundamental tópoi of the fashion system: the first showcase, the most important way to present and stage the collections, the ideas, and the style of a brand, effectively and immediately communicating the product and its entire design path.

Fashion shows, for which the dichotomy between packaging and product is disintegrating, thus become the focus of what Orvar Löfgren calls today’s catwalk economy, that is the need to communicate an increasingly appealing image blending innovation and creativity: a commercial artistic performance, where tickets are free but almost everything on the stage is for sale,[13] designed to succeed in engaging an ever-growing audience (in situ and online) and thus establish a visual, but above all emotional, relationship between designers/brands/models acting on the catwalk and the audience. [11] [12][13]

Alongside the creation of a multifaceted abacus of staging possibilities, over the years, there has been an increasingly rapid expansion of the geographical boundaries within which the current fashion system and design circles have moved, increasingly involving digital technologies and media. The voyeuristic nature of fashion shows, amplified by fruition through social media, has contributed to their consolidation as practical communication tools. Perpetuating modes that have been established for more than a century, the catwalk still represents an eagerly awaited moment, during which the novelty of products is associated with the constant research of forms of representation, spaces, and sharing. It is precisely this solid communicative value, as well as the increasing pervasiveness of messages through digital channels, that have meant that fashion communication is not only limited to sharing new aesthetics and new forms of dress, but also real political messages and decisive stances.

As a catalyst of transformations and changes, in its continuous mutations, fashion has evolved from an elite to a mass commercial phenomenon, from a production system to a communication system, increasingly in the service of spontaneous political actions. [14] Thanks to the explosion of social media, fashion shows now represent an independent and trans-disciplinary design field, in which architecture, set design, dramaturgy, performing arts, communication, and new technologies are intertwined.

The entire fashion system can be said to be enclosed between the extremes of a structure that on the one hand contemplates the artistic/creative dimension reserved to insiders and, on the other, addresses the expressive/communicative one to the public. In the fashion system, the artist’s creative impulse is expressed through the use of the multiple languages of contemporary communication, from photography to advertising, from design to fashion imagery and fashion shows, from theater and opera to cinema, radio, and television. The line between fashion culture and fashion marketing is fragile. [15]

The product presented during a fashion show, the choice of a stage, space, or city, and the definition of a precise communication strategy, all become ways for fashion to share not only a creative and productive process but, increasingly, to explicitly communicate clear political statements.

The runway finale during the Dior Cruise 2021 fashion show on July 22, 2020, in Lecce. The show was the first one after the Covid-19 lockdown.

Photo © Vittorio Zunino Celotto/2020 Getty Images

The product and its staging as a communicative system of political discourse

Although the product is no longer the sole protagonist of the fashion show, it is still the main protagonist of any form of fashion staging. The collection represents the purpose, and the fashion show is like a film premiere — the moment in which the product is presented and, above all, judged from a market perspective.

Curiosity regarding new forms of clothing makes the fashion show, season after season, the moment in which the centrality of the product is reaffirmed, renewing the anticipation that precedes the event which becomes even more significant when a new brand is presented, when innovations are introduced in terms of proportions and silhouettes (as in the historical cases of Pierre Cardin, Paco Rabanne, or Mary Quant), when new markets and new economic relationships are opened (as in the case of Giorgini’s First Italian High Fashion Show), when there are changes in the design and in the formal language of a brand - recently expressed by the increasingly frequent changes in creative direction, for instance the arrival and departure of Phoebe Philo at the creative direction of Celine, the alternations of Tom Ford and Hedi Slimane at the helm of several historical brands, or the arrival of Maria Grazia Chiuri, the first woman at the helm of Dior. Regarding the latter, it is precisely on the occasion of her debut at the helm of the Parisian maison that the Italian designer used the catwalk as a space to express not only her creative approach but also her idea of fashion and her political thinking.

“We Should All Be Feminists,” the speech given in 2012 at TEDxEuston by Nigerian-born writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, became a fashionable slogan in 2017, printed on the T-shirts presented by Chiuri in her first collection for Dior. The decision to use this phrase to mark her debut at the French fashion house was a real programmatic manifesto, meant to reiterate the need to define a specifically feminine vision of fashion design [16] and the necessity of understanding how to interpret the present as a “happy feminist.” [17]

The stage and the location as political choices

Fashion has always needed bodies to dress, and physical (and now also virtual) spaces to display the clothed bodies.

The space of the runway show now transcends the boundary of staging or the mere selection of a location, becoming an increasingly complex artifact, designed to engage with the IRL audience and to be best conveyed, through various digital channels, to a virtual one. Catwalks are increasingly becoming an all-encompassing experience, not limited to the most superficial decoration.[18]

Runway locations become relevant in defining the narrative of a collection but, at the same time, they are transformed by the way fashion uses them.[19] For fashion shows, public spaces have often been temporarily closed, and private spaces have been opened up; places inaccessible to most have been made accessible, while set design has taken the form of authentic architecture. Indeed, fashion show set design is a free-standing creative form, a new facet of the architectural project: the space of the fashion show can be seen as a microcosm capable of making the most of new products and new trends, but it can also be read as a field of experimentation, capable of offering a perspective (albeit in an ephemeral form) on society, culture, and art. And so the static form of architecture, in apparent contradiction with the mutability of fashion, “deals with dressing the body in the same way fashion does,”[20] and the choice of a place or city becomes not only a narrative choice but also a political one.

When, in 1971, some young fashion designers — among them Walter Albini, Missoni, Krizia, and Ken Scott — left Florence to show at the Circolo del Giardino in Milan, they expressed a political choice:“Against the rigid formula of the catwalks of Florence, to seek in Milan more fluid modes of expression and at the same time a more coordinated presentation of the models. These are years full of changes for Italian fashion, which is preparing to become an international phenomenon. Getting out of the Florentine formula, which was somewhat strict and organized according to a precise number of garments to be paraded in front of the audience, to start a new, more spectacular way that would become typical Milanese, also meant changing the very spirit of the fashion show. Not only do more models appear on the catwalk, but the vision of the designer is proposed.” [21]

1971 marked the beginning of an era that would see Milan as capable of catalyzing the best entrepreneurial and creative realities of Italy and beyond. Milan was chosen because it was “an industrial city, not particularly attached to its past, lacking ties to the rituals of high fashion and, on the contrary, extremely sensitive to the younger boutique. In the 1960s, the Lombard capital had been the city of the boom, of the avant-garde in the artistic field, of design and, at the end of the decade, of protest. Choosing the Lombard capital meant focusing on another Italy, one that did not live by the myth of past glories but sought an active space in modernity.”[22]

Later, fashion shows in the Red Square by Laura Biagiotti in 1995, on the Great Wall of China by Fendi in 2007, and in Havana by Chanel in 2016, have become not only scenographic choices but also choices dictated by strong political intentions.. [23]

More recently, during the Covid-19 pandemic, the act of not stopping the fashion system and opening the scenic space of the catwalk to virtual sharing, have also been political gestures. During the lockdowns, social media changed the structure of fashion shows, pushing them to redefine themselves by taking different forms — sometimes extremely technological and immaterial, sometimes, by contrast, recovering already established physical modes. On September 26, 2020, at the beginning of the first pandemic wave, Giorgio Armani decided to give a sign of resistance and resilience by confirming the fashion show but holding it behind closed doors. Thus, the Milanese designer organized a runway show without an audience in attendance, a show shared not only via social media channels and the web, but also broadcasted live through the Italian television channel La7. This was a sign of resistance and openness in a period of closures. The unique event achieved a 3% share with 685,000 viewers in the Italian territory alone; sharing this event via television broadcast with a wide audience previously excluded from this form of communication was regarded, in a period of restrictions and social distancing, as a political stance.

In pandemic times, some brands felt the need to be physically present in order to give a positive sign of resistance, resilience, and of support to the entire supply chain. The first and most persistent promoters of the need to resist the hardships imposed by the pandemic were Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pietro Beccari (at the head of Dior), who chose not to give up the live fashion show in the presence of an audience as in their view it would have meant surrendering the topical moment of fashion culture. In an interview with Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera, Beccari said: “For us, fashion is also emotion, and nothing is more emotional than a fashion show. The second reason we decided to resume the project is that we want to give a signal of hope to the whole world and indicate a reason for rebirth.” [24] Such signal manifested itself with the brand’s 2021 cruise collection fashion show, which was showcased outdoors (in Lecce’s cathedral square) and with guests in attendance.

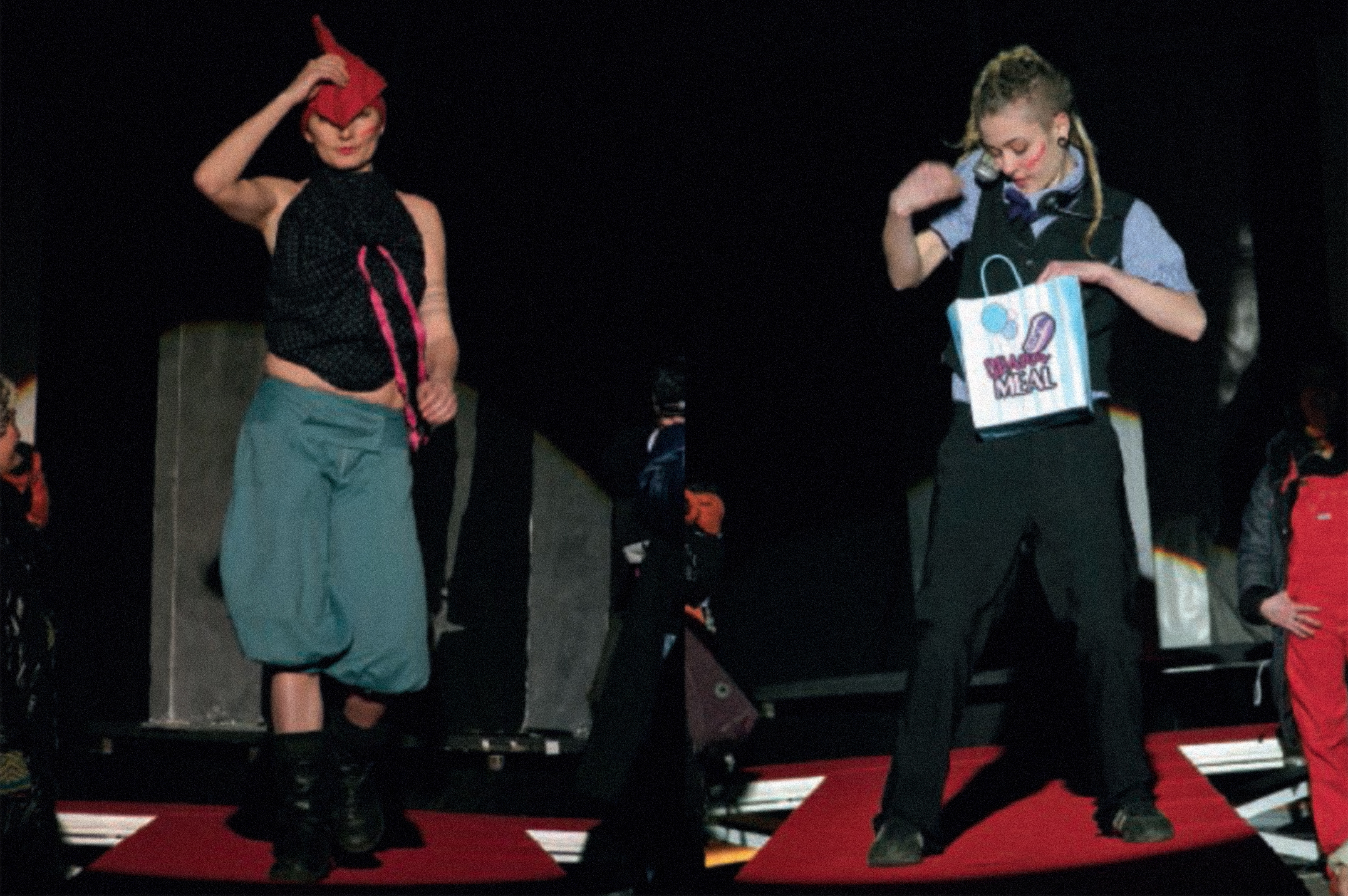

Left: A model at the Serpica Naro fashion show in February 2005. The outfit was called "Italian husbands prefer blond Romanians," the outfit was created considering the theme of work-related rather than marriage-related residence permits.

Left: A model at the Serpica Naro fashion show in February 2005. The outfit was called "Italian husbands prefer blond Romanians," the outfit was created considering the theme of work-related rather than marriage-related residence permits.Right: A model at the Serpica Naro fashion show in February 2005. The outfit was called "Call Donald Mac Center." The model ironized on the theme of a "happy call donald partner" to describe precarious young people's life hovering between the plates of a McDonald's restaurant and the phones of a call centre.

Photo © Marco Garofalo/Courtesy Serpica Naro

Politics in the form of stage and performance action

If a thought needs words, fashion needs bodies. Fashion as a language dresses the body with meanings, becoming an expression of personal and social identity; therefore, to wear is to communicate. [25][26] The body that walks the runway, its physical appearance, and the interaction created with those who witness the event, all become an integral part of fashion’s artistic design discourse. In fashion shows, the garment often transcends its physicality and becomes the subject of performance. Thus, actions designed to establish a direct and multisensory dialogue are defined, going beyond their commercial nature and becoming more of an art form capable of presenting a product, and posing a set of questions on how fashion can relate to people and society in general.[27][28]

Increasingly, fashion and the performing arts are merging. The catwalk hosts different forms of expression; events are designed to “catch the eye and appeal to the senses,” [29] and the product comes to life in the form of a performance, though it is not always clear whether the idea of the collection or its staging came first. For example, Viktor and Rolf's fashion shows, such as Russian Doll in autumn/winter 1999, Zen Garden in autumn/winter 2013, and Wearable Art in autumn/winter 2015, were true performative acts during which the designers assembled and deconstructed the clothes on the catwalk, creating a continuous flow between creative act, performative act, and product. Over the years, the fashion world has witnessed specifically theatrical stagings, from choreographies to acting — carefully planned campaigns amplified the events, communicating political and social messages through performative intent. Statements like those of Moschino in the 1990s, were not only printed or embroidered on clothes, but they also took shape on the catwalk during the theatrical runways that the Milanese designer used to stage. For example, the fall/winter 1990–1991 show titled Stop the Fashion System, was a theatrical performance with a political meaning, using irony and satire as tools to amplify the message of the collection. It was not just a fashion show but a proper dance performance, during which models and dancers moved together on the catwalk staging the struggle of ordinary people against Fashion (personified by an austere black-clad witch) in order to free the creative spirit and the liberty to dress how one wants. The dance ended with a final display of Italian flags (one of the brand’s iconic symbols) used to enshrine freedom from fashion constraints. With this action, Moschino created a communicative short-circuit, mocking the fashion system and all its social events (including fashion shows), though fitting perfectly within the system itself, albeit with its signature ironic and irreverent vision.

A non-show,[30] a proper performance, in full Moschino style, a hybrid of theatrical costumes with outsized elements, a reference to the iconography of jesters and the circus, and products taken from the street that define Kaos even more. “Moschino also advises reading the characters of dress circulating in our streets and, it remains implied, less textbook fashion images. The interpretations of the garments one encounters around the cities of Italy remain, after all, the most inspiring and familiar signs of our time. [The fashion show and collection are the staging and in the product of Franco Moschino’s request]: ‘Please leave me alone to make clothes! It’s the only thing I want!”[31]

The irreverent spirit of Moschino was then echoed over time by various realities of the fashion system, in particular by alternative groups such as the Milanese collective Serpica Naro (Fig. 04) (an anagram of San Precario, a joke in Italian to refer to the Patron Saint of 'precarious' workers). Serpica Naro was born as a provocation, as a non-existent brand created by a collective of creative activists, to raise awareness on the problem of unstable jobs and the on the issue of underpaid labor. In order to do this, the collective staged a runway show event in February 2005 during Milan Fashion Week, and "presented eight allegorical models aimed at illustrating the humiliations of precarious labor, followed by the presentation of outfits from European and Italian independent brands that did not recognise themselves as a part of the fashion world and its flattery"[32]. The entire fashion show was conceived as a protest and political stance.

More and more fashion, especially in its form of staging through fashion shows (whether in physical or digital form), is capable, as Gaugele asserts, of shaping a new arena of aesthetic politics in which designers and labels seem to compete as activists by demonstrating and claiming through their actions, taking clear stances, whether related to climate change or to labor exploitation, in support of humanitarian causes or for a social affirmation. [33]. As the age of digital communication has now opened the doors of fashion weeks to a broader audience, fashion shows have now become a new form of political manifestation which, beneath the glamorous surface, are capable of defining real manifestos and political declarations [34].

Notes: Fashion Parade

[1] Roland Barthes, Il senso della moda. Forme e significati dell’abbigliamento, trans. Gianfranco Marrone (Torino: Einaudi, 2006).

[2] Marco Ricchetti, Enrico Cietta, (eds.), Il valore della moda. Industria e servizi in un settore guidato dall’innovazione (Milano: Bruno Mondadori, 2006).

[3] Harold H. Saunders, Politics Is About Relationship: A Blueprint for the Citizens’ Century (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005).

[4] Joshua I. Miller, “Fashion and Democratic Relationships”, in Polity, vol. 37, n. 1, 2005, pp. 3–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3877060. Accessed 25 October 2022.

[5] Giannino Malossi (ed.), Il motore della moda. Spettacolo, identità, design, economia: come l’industria produce ricchezza attraverso la moda (New Yorlk: The Monacelli Press,1998).

[6] Georg Simmel, La Moda (Roma: Mimesis, 2015).

[7] Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London: Continuum, 2004), 39.

[8] Eleonora Fiorani, Moda, corpo, immaginario. Il divenire moda del mondo fra tradizione e innovazione (Milano: POLI.design, 2006), 17.

[9] Diane Crane, Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender, and Identity in Clothing (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), 1.

[10] Maya Singer, “Power Dressing: Charting the Influence of Politics on Fashion”, in Vogue.com, 17 September 2020; https://www.vogue.com/article/charting-the-influence-of-politics-on-fashion. Accessed 25 October 2022.

[11] Francesca Ala, et al., Lo spazio architettonico della sfilata di moda (Roma: Gangemi Editore, 2019), 9.

[12] Orvar Löfgren, “Catwalking and Coolhunting: The Production of Newness”, in Magic, Culture and the New Economy, eds. Orvar Löfgren, Robert Willim, (Oxford-New York: Berg, 2005), 64.

[13] Rosie Findlay, “Things to Be Seen: Spectacle and the Performance of Brand in Contemporary Fashion Shows”, in About Performance nn. 14-15, 2017, 105.

[14] Vittorio Linfante, Catwalks. Le sfilate di moda dalle Pandora al digitale (Milano: Bruno Mondadori, 2021), 1.

[15] Daniela Calanca, Storia sociale della moda (Milano: Bruno Mondadori, 2002), 82.

[16] Vittorio Linfante, “What Women Designer Want. The Female Point of View in the Fashion Creative Process”, in PAD. Pages on Arts and Design, n. 18, 2019, 59.

[17] Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: ‘I decided to call myself a Happy Feminist’”, in The Guardian, Fri 17 Oct 2014, retrived on https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/oct/17/chimamanda-ngozi-adichie-extract-we-should-all-be-feminists

[18] Vittorio Linfante, Chiara Pompa, “Space, Time and Catwalks: fashion shows as a multilayered communication channel”, in ZoneModa Journal, vol. 11, n. 1, 2021, 31.

[19] John Potvin, “Introduction: Inserting Fashion into Spaces”, in The Places and Spaces of Fashion, 1800-2007, ed. J. Potvin (New York: Routledge, 2009), 9.

[20] Deborah Fausch et al., Architecture in Fashion (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 7.

[21] Simona Segre Reinach, “Putting it together”, in Walter Albini e il suo tempo. L’immaginazione al potere, eds. Maria Luisa Frisa, Stefano Tonchi (Venezia: Marsilio, 2010), 18.

[22] Enrica Morini, Storia della moda XVIII-XXI secolo (Milano: Skira, 2017) 455.

[23] Valeria Iannilli, Vittorio Linfante, “Nuovi percorsi della moda tra globale e locale. Dai grandi centri alla disseminazione culturale del fashion system”, in Zonemoda Journal, vol. 9, n. 2 (2019), 161.

[24] Michele Ciavarella, “Dior: Fashion restarts from Cruise in Lecce”, in Corriere della Sera - Style Magazine, June 22, 2020, https://style.corriere.it/moda/dior-la-moda-riparte-dalla-cruise-lecce/. Accessed 22 October 2022.

[25] M. McLuhan, La moda è linguaggio, in McLuhan nello spirito del suo tempo, ed. Nicola (Roma: Pentecoste Armando Editore, 2015), 197.

[26] Eleonora Fiorani, Moda, corpo, immaginario. Il divenire moda del mondo fra tradizione e innovazione (Milano: POLI.design, 2006), 9.

[27] RoseLee Goldberg, Performance Now: Live Art for the 21st Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018), 7.

[28] Jonah Westerman, The Dimensions of Performance, in https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/performance-at-tate/dimensions-of-performance. Accessed 22 October 2022.

[29] Rosie Findlay, “Things to Be Seen: Spectacle and the Performance of Brand in Contemporary Fashion Shows”, in About Performance nn. 14-15, 2017, 102.

[30] Antonella Sabbagh, “Stop the Fashion System! Ovvero Moschino e le ‘non-sfilate’”, in Moda In, n. 56, August-September 1990.

[31] Mariuccia Casadio, “La moda è il messaggio”, in Vogue Italia, n. 478, April 1990, 64.

[32] Domenico Quaranta, “Impatto Digitale”, in Il Nuovo Vocabolario della Moda Italiana eds. Paola Bertola, Vittorio Linfante, (Firenze: Mandragora, 2015), 44–49.

[33] Elke Gaugele, Aesthetic Politics in Fashion (Vienna: Sternberg Press, 2014), 205.

[34] Vittorio Linfante, “Fashion Statements. Fashion Communication as an Expression of Artistic, Political and Social Manifesto between Physical and Digital”, in Fashion Communication. Proceedings of the FACTUM 21 Conference, Pamplona, Spain, 2021, eds. T. Sadaba, et al. (Belin: Springer, Berlin 2021), 77–90.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics