David Hopwood is Programme Director: Product at London College of Fashion, UAL. A graduate of the Royal College of Art in MA Fashion Womenswear, David has a solid and continuing developing knowledge of the fashion industry both in the UK and Europe. David has worked in several different design and production roles as well as special projects with brands, artists, and magazines.

Lilia is a UK-based Singaporean designer, researcher, and educator whose work bridges fashion, tradition, and critical pedagogy. With expertise in sustainable practice and global design histories, they teach at London College of Fashion, UAL, exploring dress as cultural knowledge through conscious, embodied methods and empathetic approaches to fashion education.

A full PDF version of this visual essay is available here.

EMPATHY AS DISRUPTION

“Committed acts of caring let all students know that the purpose of education is not to dominate, or prepare them to be dominators, but rather to create the conditions for freedom. Caring educators open the mind, allowing students to embrace a world of knowing that is always subject to change and challenge." -bell hooks

HELLO and welcome

We are Lilia and David, and we teach on the BA (Hons) Fashion Design and Development (FDD) course at London College of Fashion, UAL.

We have 350+ students around the world, and we work with around 15-18 students/groups.

On FDD, we recognize the challenges facing the global fashion industry and encourage our students to re-think current industry practices through innovation, technology, and future-thinking. Our students learn to develop their own individualized practice-led approaches that engage directly with real-world issues; designing solutions and product with empathy, critical thinking, and sustainable methodologies.

WE LOVE PEOPLE

As educators we are conscious of our own experiences as designers and students.

We teach, create, and learn with and through empathy, embedding it within our pedagogical practices.

In this article, we reflect on how we build empathy within fashion education:

- through the sharing of our positionalities

- being transparent about our experiences and vulnerabilities

- acknowledging the structures within the fashion industry

- embracing a world that is subject to change and challenge

Through empathic listening, we work to actively diffuse the power imbalances inherent within student and tutor relationships, building trust in a holistic manner.

Using student examples from BA Fashion Design and Development (FDD), we suggest ways in which empathy-led teaching pedagogies create space for students to define fashion for themselves, leading to innovative, diverse, and inclusive bodies of work that demonstrate student agency and visions of what fashion could be.

EMPATHY AS DISRUPTION from a FDD perspective

thinking about boundaries/ sharing

empathy can:

- Enable us as educators to always break away from students being passive receivers of information, but we can utilize the knowledge our empathetic observations have given us.

- Dismantle power - not just teacher and students but our power with others in the world and outside the classroom.

- Give insights to help us develop how we teach unit content and create resources.

- Aid us in how we develop our course curriculum and scaffold our students’ learning journeys to enable students to engage with their learning and self-development.

- Create confidence in being curious and not being afraid to fail.

empathy can’t:

- Be underestimated. Working with the students and being present can lead to fatigue and so it is important to build boundaries with how you work with your students.

- Be the only working method. Empathy works as disruption in how it is used alongside critical thinking and sustainable methodologies.

- Suit everybody. It is important to recognize ways people can build empathy into their teaching practice.

EMPATHY AND SYSTEMS THINKING

"Fashion design education itself has been a small self-referential niche within the whole system. This isolation is possibly coming to an end, given the acknowledged impact of fashion on global economies and society, and the need for it to engage, as for all other sections, in supporting a consistent transition of our world towards more sustainable paradigms." - P. Bertola

We have been exploring the space outside of the binary lines of the fashion education system.

Transforming and reshaping how we teach, so we move away from passive knowledge–focused teaching, "feeding an enduring demand in prospective students, who are usually fascinated by fashion for its media and social impact, driven by individualism and not pragmatically informed by the professional context of designing and developing real products in a dramatically changing world." - P. Betola

The fashion industry is formed of multiple systems intersecting and interacting with each other, and in fashion education it is vital that we find ways to break down these systems so students are exposed to the industry within academic spaces.

Using the curriculum to design a student + staff learning journey has enabled us to put systems in place to:

SCAFFOLD

- The learning journey for staff and students.

- Doing this enables us to create unit teams that bring their knowledge + skills to the unit.

- We plan together as a team finding ways to scaffold the transition between year groups.

- See the units as products which have their own identities but also align with the other units in how we build in knowledge and skill delivery.

FIND SPACE to REACT, ADAPT + be AGILE

- For our students.

- In embedding industry into the course curriculum.

- In finding space between the units for staff and students to reset.

USE EMPATHY to ENABLE STUDENTS

- To actively listen.

- To explore collaboration and ways of working across the school and college.

- To develop skills, agency, and confidence.

As a team we have worked together to co-develop strategies for:

MUTUAL TRUST + CO-CREATION

This has taken time for us to develop as a team.

We are a large team of 10 permanent staff and 6 hourly paid lecturers.

Everyone has different schedules, so finding time in the working week to meet as unit teams and the FDD team is challenging.

When developing ways of creating and working as a team it is necessary to recognize how everyone receives and retains information. Context and transparency are key to this.

We've done a lot of work on confidence building within the team to bring out each other’s potential and understanding of empathy in education.

As a course team we've developed systems that allow us to play with our curriculum—how we teach and create spaces for ourselves and our students to be curious and explore in safe environments.

"On the one hand, decolonization involves dismantling structures that perpetuate the colonialist status quo and addressing unbalanced power dynamics...

For everyone, to decolonize means to learn about ourselves, our places of origin, and our relationships to the communities in which we live and the people with whom we interact." - S. Covington

Decolonizing with empathy when applied within teaching is not simply about what we teach but how we teach.

The teacher-student power imbalance is the first structure we have sought to reconstruct. This is not an equalizing but an opening.

Being open to the fluid nature of power dynamics in this relationship, recognizing how we affect each other, and being conscious of the impact of our words and actions.

In this framework, both tutor and student are ready to learn more about themselves and each other and recognize where we have and lack power.

"Power" in this context is transformed from a concept of domination and authority over another to a source of personal agency.

We discuss this framework in action below.

EMPATHY - in action on FDD

We will present some student examples from a snapshot of our units across the three years of FDD below. The three units chosen are excellent examples of the work we have done on the FDD curriculum and student/staff learning journey. This is evident in the student outputs and engagement with the unit.

“Through empathic listening, we work to actively diffuse the power imbalances inherent within student and tutor relationships, building trust in a holistic manner.”

In 2022/23, we redesigned FDD through the reapproval process. We were re-writing units, learning outcomes, assessment criteria, using this opportunity to create space within our units for our students to explore their identities and for us to bring our own educational and industry experiences to FDD.

We have a diverse student population in FDD and we were seeing some beautiful personal responses to the units, but we felt we needed to step off the binary lines the course followed and reimagine the course with the following aims:

To use our empathy to understand our experiences, allowing us to recognize and learn from our own vulnerabilities and how we can employ these in how we teach.

Intro to FDD was the first unit we could test from the new course handbook.

This is the first unit we deliver and is the first chance for us to create trust with our new students.

This unit introduces the students to us as a course and as their tutors. We have developed sessions where students co-create; working on their zines and through conversation, we ask them to explore their chosen garment through different lenses.

We ask them to find ways to understand their chosen garment through different research methods and how they document these in their zines.

"The empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable whilst encouraging students to take risks. Professors who expect students to share confessional narratives but who themselves are unwilling to share are exercising power in a manner that could be coercive." - bell hooks

We have a diverse student population in FDD and we were seeing some beautiful personal responses to the units, but we felt we needed to step off the binary lines the course followed and reimagine the course with the following aims:

- To play with those "traditions" that are present in a lot of undergraduate courses within the UK.

- To identify and address where each unit did not challenge the students to engage or to show their own personal evolution as they progressed through the course.

- To question where we were not giving them the tools or opportunities to be exposed to different ways to create, make, present their work and themselves with meaning.

- To start in year 1 day 1 instilling the ethos of being "industry-ready" and to stand apart from their peers in a crowded graduate job market.

To use our empathy to understand our experiences, allowing us to recognize and learn from our own vulnerabilities and how we can employ these in how we teach.

Intro to FDD was the first unit we could test from the new course handbook.

This is the first unit we deliver and is the first chance for us to create trust with our new students.

This unit introduces the students to us as a course and as their tutors. We have developed sessions where students co-create; working on their zines and through conversation, we ask them to explore their chosen garment through different lenses.

We ask them to find ways to understand their chosen garment through different research methods and how they document these in their zines.

EMPATHY TO CREATE TRUST

"The empowerment cannot happen if we refuse to be vulnerable whilst encouraging students to take risks. Professors who expect students to share confessional narratives but who themselves are unwilling to share are exercising power in a manner that could be coercive." - bell hooks

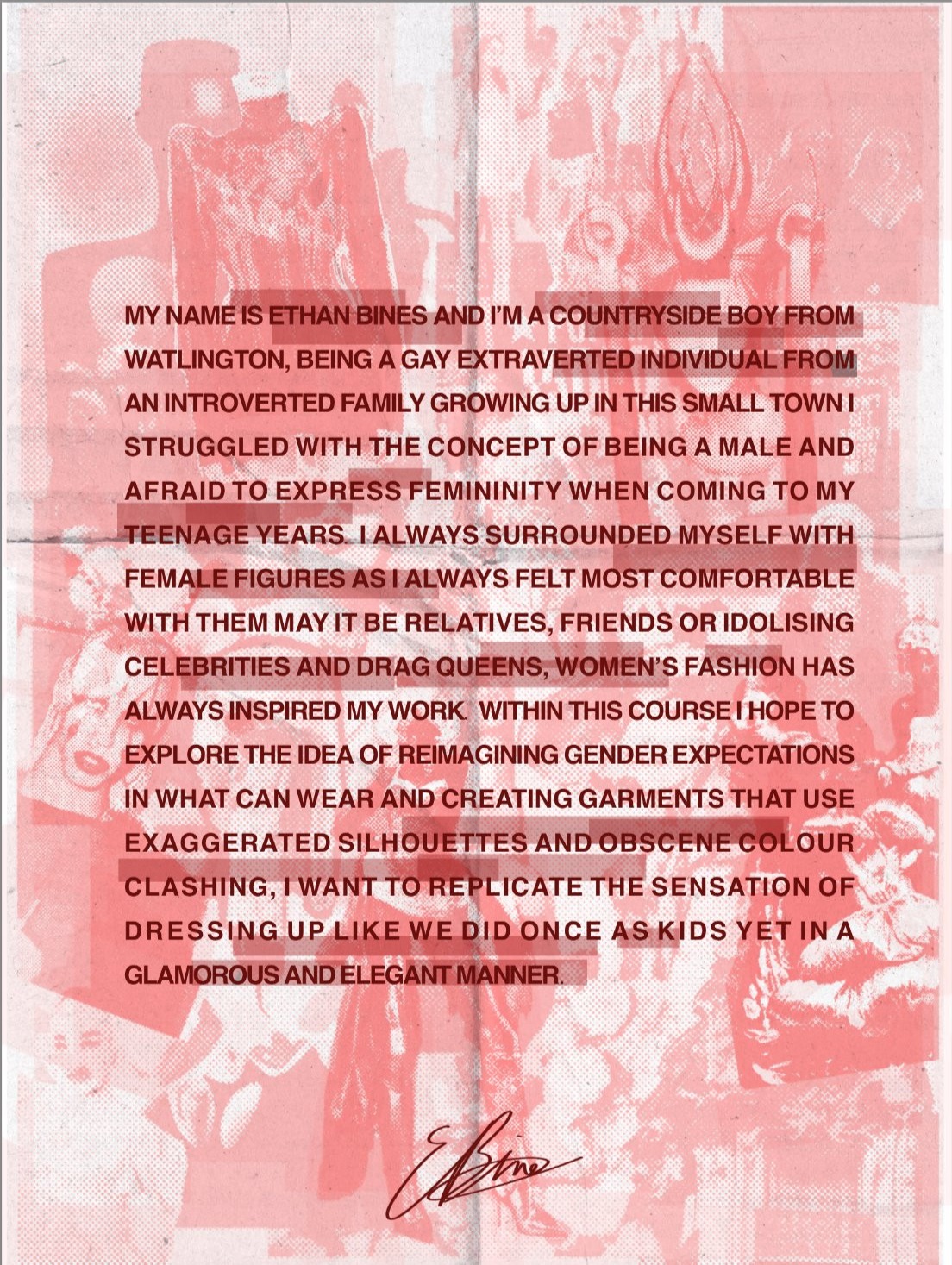

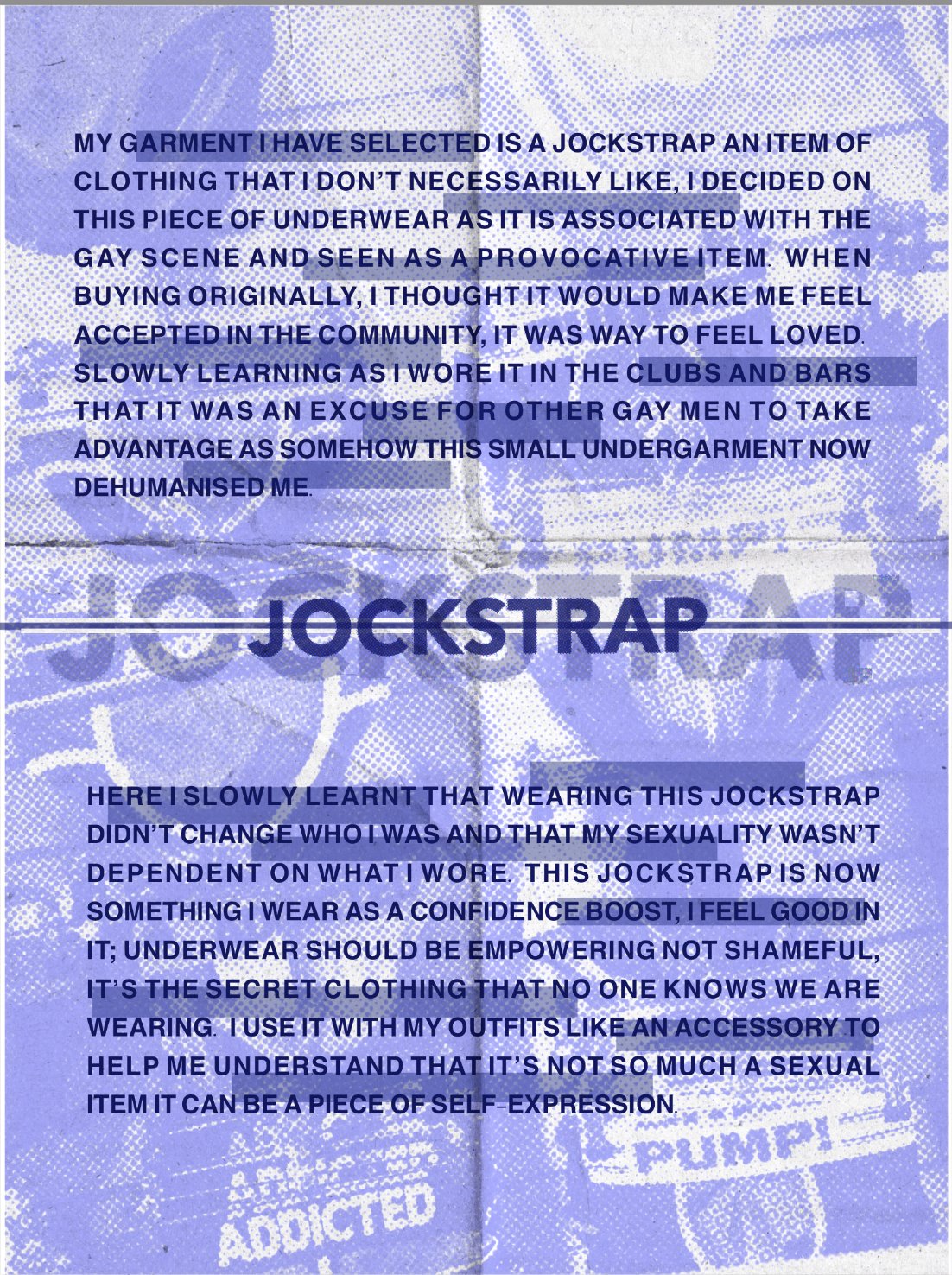

FDD First Year. Intro to FDD Unit. Ethan Bines.

FDD First Year. Intro to FDD Unit. Ethan Bines.EMPATHY TO CREATE TRUST

Breaking from bias (empathy to create trust)

On FDD the first unit our students work on is Intro to FDD. This is their first unit, the first time they work with us and their peers in a new space and city.

We recognize we are asking a lot of our students in choosing their garment, bringing it to class, in turn opening themselves up to their own and others’ opinions, assumptions, and biases.

We ask that they have a personal connection to the garment they choose. We do this as we see it as a way for them to enter the teaching space with a garment that they trust.

In this seven-week unit, through a series of lectures and workshops, they work together in peer groups researching, examining, and understanding their own relationship to their chosen garment.

Students engage in a variety of "playful" ways in how they research and start to build their own knowledge and insights.

As educators our intention is to start the process of our students finding their own way with how they approach research, how they use it to learn to break from bias, and to create work that shows their creative personality and their empathy to how they present their findings.

Our students create a digital 'zine,’ and two pages from Ethan's zine have been presented here.

Ethan used this as a way to understand himself—to understand not only his reasons for choosing this garment but also to acknowledge how his garment is perceived by others within society and by him.

His chosen garment is worn by so many different people, it has an obvious function, but what really captured Ethan was the meaning different communities place on the garment.

How something practical can signal to someone else who you are.

Ethan used his research, his self reflection, to recognize the bias this garment has—how through his own lived experiences wearing the garment he was able to understand how other people reacted to him. He explored his relationship with himself and his garment, giving him an understanding of codes of wear and his positionality.

Our work on this unit involves how we employ empathy as a form of understanding our positionally through a chosen garment. The bell hooks quote above highlights that this is not a one-way street.

"Professors who expect students to share confessional narratives but who themselves are unwilling to share are exercising power in a manner that could be coercive." - bell hooks

In developing the way we deliver this unit we also present our chosen garments to the students, using this as a way to develop mutual trust with the students.

We give the students the freedom of choice about how they present their zines, the types of research they decide to do into their chosen garment.

We do structure the delivery of the unit, recognizing that the ways we explore how we might research and apply this knowledge could be overwhelming.

We use systems thinking in how we scaffold the delivery of content, breaking down the "process" so students can start to embed this into their own practice.

FDD First year. Intro to FDD Unit. Ethan Bines.

FDD First year. Intro to FDD Unit. Ethan Bines.EMPATHY AS AWARENESS

Disrupting hierarchies of power (empathy as awareness)

On FDD, we use sustainable supply chain design as a means of questioning hierarchies of power. Students take a systems approach to design, questioning the role of the designer and their relationship with people, material, and nature.

As part of their fashion brand concept development, students are asked to design a sustainable supply chain that reflects their ethos and values, reimagining more equitable relationships between:

Designer – nature

Designer – people they work with / impact upon

Designer - material

At the heart of this exercise is the recognition that designers are part of a complex ecosystem. The ability to empathize with not just people but all the resources that feed into this system allows designers to imagine ways of manufacturing that aim to have positive social and economic impacts.

In this example, Clara explores the idea of localism, which Fletcher and Klepp describe as a process that subordinates economic decisions to communities and nature. It is typically small-scale, characterized by self-reliance, practices shaped by traditions, necessity, climate, and a distributed form of authority, leadership, and political power. [1]

Within this context, supply chain and design decisions are shaped by a region’s natural factors and by what is intriguing and vibrant in a place to ensure its long-term prosperity.

Whereas the forces of globalization act centrifugally, moving away from the distinction of a specific ecosystem or place, Fletcher and Klepp see localism as a centripetal movement, concentrating economic and political power inside communities.

In the process of designing sustainable supply chains, students thus explore the possibilities of a "decentralised textile and clothing system reflecting ecological conditions, changed economic priorities, community empowerment, heterogeneous products, local stories, myriad dress practices, and fewer goods." [2]

FDD Second Year. Fashion Production Future Technologies (FPFT) Unit. Clara Avrielle Effendi.

FDD Second Year. Fashion Production Future Technologies (FPFT) Unit. Clara Avrielle Effendi. FDD Final Year Concept Development & Product Design Realisation. Jade Chrysanthe Guims

FDD Final Year Concept Development & Product Design Realisation. Jade Chrysanthe GuimsChallenging fashion norms

In the 2022 Fashion Inclusivity and Diversity UK Report, Tamara Sender Ceron writes;

"There have been big strides made by fashion retailers and brands over the last few years to become more inclusive and diverse, but more still needs to be done to embrace consumers of all sizes, ages, ethnicities, body abilities, genders and sexualities. Amid a cost-of-living crisis, understanding the struggles that these under-represented consumers face when buying fashion is key for brands to increase their appeal among these groups and drive spending."

On FDD, we create spaces to listen.

We acknowledge our own lack and stay open to learning. Allowing for a diversity of voices to be heard.

We challenge the myth of the "star" designer, a common narrative that continues to obscure the reality that fashion is created by the plural not the singular.

We encourage students to connect with their body, their consumer, their community. To observe, empathize, and learn about their needs.

We recognize that becoming aware of one's positionality can create vulnerability, but the process of unpacking these complex intersections brings with it a renewed sense of creative agency.

In the 2022 Fashion Inclusivity and Diversity UK Report, Tamara Sender Ceron writes;

"There have been big strides made by fashion retailers and brands over the last few years to become more inclusive and diverse, but more still needs to be done to embrace consumers of all sizes, ages, ethnicities, body abilities, genders and sexualities. Amid a cost-of-living crisis, understanding the struggles that these under-represented consumers face when buying fashion is key for brands to increase their appeal among these groups and drive spending."

On FDD, we create spaces to listen.

We acknowledge our own lack and stay open to learning. Allowing for a diversity of voices to be heard.

We challenge the myth of the "star" designer, a common narrative that continues to obscure the reality that fashion is created by the plural not the singular.

We encourage students to connect with their body, their consumer, their community. To observe, empathize, and learn about their needs.

We recognize that becoming aware of one's positionality can create vulnerability, but the process of unpacking these complex intersections brings with it a renewed sense of creative agency.

FDD Final Year Concept Development & Product Design Realisation. Jade Chrysanthe Guims

FDD Final Year Concept Development & Product Design Realisation. Jade Chrysanthe Guims

In her final year, Jade created an inclusive womenswear brand that celebrated her culture and personality.

The clothes were designed to fit herself and the women that make up her consumer and community—friends and work colleagues. These women became part of the design process, and their feedback on size, fit, print types, and ways of dressing were incorporated into the collection design.

The Madras print, which is a traditional cloth used in the French West Indies, was adopted and adapted to suit contemporary tastes.

In the image below, we see Jade's work colleague Vera giving feedback on what scale and color of Madras print suits her body.

We encourage our students to co-create with their wearers, actively soliciting feedback on what they think and feel about a design.

Just as we recognize the importance of the designer-wearer relationship, we adopt the same approach in our individual tutorials with each student. Their project direction is co-created through conversation where we see the tutor as a guide who asks questions (rather than provides quick solutions, or worse, passes judgement).

Tutors are not gatekeepers or tastemakers.

Open questions might take the form of:

"How would you like to proceed?"

"Which would you prefer and why?"

"Choose your favorite 3 designs"

"What is the key message you would like to communicate?"

The purpose of these tutorials is to help students approach design both through critical thinking and intuitive decision making, enabling them to confidently make decisions for themselves in the future.

The clothes were designed to fit herself and the women that make up her consumer and community—friends and work colleagues. These women became part of the design process, and their feedback on size, fit, print types, and ways of dressing were incorporated into the collection design.

The Madras print, which is a traditional cloth used in the French West Indies, was adopted and adapted to suit contemporary tastes.

In the image below, we see Jade's work colleague Vera giving feedback on what scale and color of Madras print suits her body.

We encourage our students to co-create with their wearers, actively soliciting feedback on what they think and feel about a design.

Just as we recognize the importance of the designer-wearer relationship, we adopt the same approach in our individual tutorials with each student. Their project direction is co-created through conversation where we see the tutor as a guide who asks questions (rather than provides quick solutions, or worse, passes judgement).

Tutors are not gatekeepers or tastemakers.

Open questions might take the form of:

"How would you like to proceed?"

"Which would you prefer and why?"

"Choose your favorite 3 designs"

"What is the key message you would like to communicate?"

The purpose of these tutorials is to help students approach design both through critical thinking and intuitive decision making, enabling them to confidently make decisions for themselves in the future.

CAN EMPATHY BE EMPLOYED AS A POWERFUL TOOL FOR CHANGE?

Empathy does not come easy. It can burn you out, create fatigue in how you teach and develop resources and content, but if used with self-care, alongside critical thinking and sustainability, empathy can be a part of how the course becomes a space of mutual trust, co-creation, and curiosity.

To do this, we keep evolving and adapting the course curriculum, and we talk during the unit and post-assessment about:

- our reflections on the units.

- the flow, delivery of workshops, the interactions, and areas where we had to plug gaps.

- the previous year and thinking of how the upcoming Y2 Block 2 units could react to these insights.

- how we scaffold the journey between years.

- how we work with different teams within the school and college.

- analyzing the cohort’s personalities and approaches and how we can adapt and work with them.

We can analyze the above in relation to university datasets, metrics, unit attainment, and retention. These data do not show the real picture—the time each team member puts into their work to realize those breakthrough moments with students, seeing their pride and confidence in their work, in their concepts, how they talk and present.

These data do not show the goodwill and extra hours the team puts in to really create and foster those connections with our students, which then can lead to trust and the use of empathy.

The data do give us the opportunity to understand where we should focus our attention and enable us to see how effective our teaching practices have been.

HOW DO WE DO THIS:

Empathy does enable us to ask questions about the course, the industry, and world and find ways to bring this into the ways we teach and interact with our students and each other.

We work in collaboration with colleagues in facilitating workshops with the team, and in doing so over the last five years we have explored ways we can do this.

Co-teaching has given us so many opportunities to use empathy in different modes and (referring back to Bertola) break down these fashion industry systems so students are given the exposure to the industry within academic spaces.

Co-teaching allows multiple academic voices, their expertise, and experience to be used effectively. In our delivery we debate and, through sharing experiences, we create spaces for students to define fashion for themselves, demonstrating student agency and visions of what the fashion industry could be.

We co-teach with 3–5 academics in the room and multiple groups. FDD has on average six groups in a year, so bringing the cohort together allows for parity in our teaching and an opportunity for our students to work with other team members.

Active interaction has been developed, referring to Betola's idea of students being able to work in multidisciplinary contexts and how we can move away from passive knowledge–centered learning.

We have developed resources accessible to all which provide students with core skills. Doing this means we can then explore other skills and ways to develop problem solving, system thinking, team working, and "integrate socially responsible principles and practices into design and product development strategies and processes." [3]

We have moved away from resource-reliant skills delivery and now use group work, applying methodologies to analyze and critique and problem solving activities. Creating asynchronous resources enables us the time and space within the teaching sessions to explore in more granular detail, using the asynchronous resource as a starting point. These resources are usually recordings with a PDF and students are asked to watch them before sessions, alongside preparing tasks for peer feedback and group work.

YES, BUT WITH CLEAR BOUNDARIES

We rarely say NO to our students when they present their concepts. We work with them to find ways to realize their ideas into fashion product. We problem solve and adapt our delivery to build confidence in their abilities.

Doing this requires empathy, to read what the student needs and to reframe how we speak, position our body, and use our power to defuse any power dynamic between ourselves and our students.

Our aim is not to become their creative director nor their best friend and confidant.

Our aim is to become a part of their fashion process and build mutual trust in a holistic manner.

WE LOVE PEOPLE

Notes: Empathy as Tool for Change

[1] K. Fletcher, and I. Grimstad Klepp. “A note from the editors of Fashion Practice,” Fashion Practice, 10(2), pp. 133–138, (2018). http://doi.org/10.1080/17569370.2018.1458500.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Paola Bertola. “Reshaping fashion education for the 21st Century world” in Nimkulrat, N., Piper, A., Ræbild, U. (Eds.) Soft Landing (Finland: Aalto University Schools of Arts, Design and Architecture, 2018): 7-14.

Additional Resources: Empathy as Tool for Change

Centre for Sustainable Fashion (2021). Fashion Values. fashionvalues.org.

A. Coplan. “Will the real empathy please stand up? A case for a narrow conceptualization,” The Southern Journal of Philosophy, 49, pp.40–65, (2011). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-6962.2011.00056.x.

S. Covington. “Decentering and decolonizing fashion and dress” in The Meanings of Dress (London: Bloomsbury, 2024). https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/discover/bloomsbury-academic/blog/featured/decentering-and-decolonizing-fashion-and-dress/.

A. Fuad-Luke. Design Activism: Beautiful Strangeness for a Sustainable World (London; Sterling, VA: Earthscan, 2009).

L. Gardner, and D. Mohajer (Eds.). Radical Fashion Exercises: A Workbook of Modes and Methods (The Netherlands: Valiz, 2023).

A. Grove O'Grady. “Performing empathy: Using theatrical traditions in teacher professional learning,” Teachers and Curriculum, 22(2), pp17–24, (2022).

bell hooks. Teaching Dommunity : A Pedagogy of Hope (New York: Routledge, 2003).

bell hooks. Teaching to Transgress : Education as the Practice of Freedom (New York: Routledge 1994).

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics