Keira Moore is a PhD Candidate in Textile Technology Management at North Carolina State University. Keira's concentration is Consumer Behavior, with a specialization in Race, Anti-Racism, and Inequality Studies as it relates to marginalized populations purchasing patterns. Specifically, Keira's research sits at the intersection of identity and consumerism and how sociocultural factors ultimately shape the lens through which racialized consumers decide who, what, and where to purchase. Outside of academia, Keira loves indoor cycling, trying new restaurants, and spending time with her cat, Keiko.

Maya Revell (she/her) is a 3rd year PhD Candidate in Environmental Studies, Science, and Policy at the University of Oregon. She has a focal concentration in Critical and Sociocultural Studies in Education and a secondary concentration in Indigenous, Race, and Ethnic Studies. Broadly, her research focuses on Black relationships to land and water, Black-Indigenous solidarities, and co-creating livable futures.

Alliyah Moore is a first-gen Sociology PhD student at Howard University whose research interests are Black feminist theory, placemaking, and social movements. As an HBCU advocate, she received her B.A. in Political Science from Southern University and A&M College and M.S. in Sociology from Morgan State University. She was a Fellow at the Summer Institute in Anti-Racist and Decolonizing Research 2023. When she's not in class, you’ll find her hiking and photographing the U.S. National Parks.

Barbie, originally a plastic, white, and cisgender female-presenting doll figure, was created on March 9, 1959, to inspire all girls and women to imagine they could be anything. [1] According to Janelle Sessoms’ article titled “Barbie’s Revival of Hype Femininity is the ultimate Act of Feminism,” Barbie represents the ultimate feminist icon and the standard of femininity. [2] The lyrics of Aqua’s ‘Barbie Girl’ illuminates just that by stating –“I’m a Barbie girl in the Barbie world, Life in plastic, it’s fantastic, You can brush my hair, undress me everywhere, Imagination, life is your creation.” The question presents itself: In a capitalist, cisheteropatriarchal, and colonial context, has the delivery of this message of femininity and inclusivity through the production of Barbie done more harm than good? More specifically, we want to understand how the paradoxical aspects of the film, and the doll that inspired it, affect the subjectivities of viewers of color.

Feminist standpoint theorists have long argued that knowledge is socially situated, that marginalized peoples have unique knowledge due to their socio-political positions, and that attending to power relations in research requires acknowledging marginalized experiences as starting points. [3] Within feminist standpoint theory, Black feminist standpoint scholars have argued that Black women have and produce specialized knowledge about Black women, as this production involves “an interpretation of Black women’s experiences by those who participate in them.” [4][5] Black feminist standpoint epistemologies convey overlapping and tripled oppressions that often go unnoticed, attend to the nuanced subjectivities and experiences of Black women and girls, and hold space to imagine beyond the confines of white supremacist, capitalist, and cisheteropatriarchal societies.

First, as three Black women in the academy, we recognize our privilege to access and share knowledge. By dissecting the film in totality, we investigate its intentionality as we question whether Barbie is an example of a satirical work that encourages audiences to think critically about patriarchal and oppressive structures or a piece that mocks those current social and political structures. Additionally, we investigate anti-Blackness and the depiction of Barbie Land as an ideal feminist utopia. Through our Black feminist standpoint lens, we examine power imbalances impacting marginalized groups through neoliberal policies and practices. By situating Barbieland in the longstanding history of speculative fiction that centers the desires of white audiences through the creation of settler futurities, we aim to show how the utopic premise of Barbie fundamentally disregards and erases the current realities and possible futures of Black, Indigenous, and other racialized women. [6][7] That said, through this reflectional piece, we reflect on how the deeply embedded nature of whiteness shapes our abilities to imagine alternative realities as we urge our readers to create their own.

We analyze the 2023 Barbie-Warner Brothers Production using excerpts and stills from the film that highlight the irresolvable contradictions between the production’s alternative structures and our socio-political realities. Considering these paradoxical elements, we prompt readers to explore the possibilities for Barbie in current societal conditions and reimagine its future outside destruction.

“Thanks to Barbie, all problems of feminism have been solved”

Following extensive global marketing, Barbie fans eagerly anticipated the Turbo-Charged release of Barbie, the film—for some an opportunity to relive childhood memories, for others to create new ones with friends and family. According to Sessoms, “Playing with Barbie told us that girls could do anything, and we didn't have to sacrifice our societally constructed understanding of "girlhood" to get there.”[2] However, the movie left some viewers questioning the intentional, binary constructions of feminism and womanhood and the pronounced contradictions of the portrayal of several intersections. Below, we explore some of our own such reactions to the film, individually and in conversation with one another.

First, Alliyah Moore begins to delve into her own uncertainty with director Greta Gerwig’s presentation of modern, intersectional feminism. Secondly, Keira Moore reflects on the invisibility Black and Brown women face in relation to their lived experiences in the modern world of “color blindness” and the insidious new face of American racism. Next, Maya Revell questions how the film’s portrayal of humanity relies on the exclusion of Black and Brown people, particularly women, and their experiences in the world. The authors conclude by emphasizing the film's denouement and advocating for a more realistic and impartial perspective, enabling readers to envision their own conclusion.

Feminist standpoint theorists have long argued that knowledge is socially situated, that marginalized peoples have unique knowledge due to their socio-political positions, and that attending to power relations in research requires acknowledging marginalized experiences as starting points. [3] Within feminist standpoint theory, Black feminist standpoint scholars have argued that Black women have and produce specialized knowledge about Black women, as this production involves “an interpretation of Black women’s experiences by those who participate in them.” [4][5] Black feminist standpoint epistemologies convey overlapping and tripled oppressions that often go unnoticed, attend to the nuanced subjectivities and experiences of Black women and girls, and hold space to imagine beyond the confines of white supremacist, capitalist, and cisheteropatriarchal societies.

First, as three Black women in the academy, we recognize our privilege to access and share knowledge. By dissecting the film in totality, we investigate its intentionality as we question whether Barbie is an example of a satirical work that encourages audiences to think critically about patriarchal and oppressive structures or a piece that mocks those current social and political structures. Additionally, we investigate anti-Blackness and the depiction of Barbie Land as an ideal feminist utopia. Through our Black feminist standpoint lens, we examine power imbalances impacting marginalized groups through neoliberal policies and practices. By situating Barbieland in the longstanding history of speculative fiction that centers the desires of white audiences through the creation of settler futurities, we aim to show how the utopic premise of Barbie fundamentally disregards and erases the current realities and possible futures of Black, Indigenous, and other racialized women. [6][7] That said, through this reflectional piece, we reflect on how the deeply embedded nature of whiteness shapes our abilities to imagine alternative realities as we urge our readers to create their own.

We analyze the 2023 Barbie-Warner Brothers Production using excerpts and stills from the film that highlight the irresolvable contradictions between the production’s alternative structures and our socio-political realities. Considering these paradoxical elements, we prompt readers to explore the possibilities for Barbie in current societal conditions and reimagine its future outside destruction.

“Thanks to Barbie, all problems of feminism have been solved”

-The Narrator

Following extensive global marketing, Barbie fans eagerly anticipated the Turbo-Charged release of Barbie, the film—for some an opportunity to relive childhood memories, for others to create new ones with friends and family. According to Sessoms, “Playing with Barbie told us that girls could do anything, and we didn't have to sacrifice our societally constructed understanding of "girlhood" to get there.”[2] However, the movie left some viewers questioning the intentional, binary constructions of feminism and womanhood and the pronounced contradictions of the portrayal of several intersections. Below, we explore some of our own such reactions to the film, individually and in conversation with one another.

First, Alliyah Moore begins to delve into her own uncertainty with director Greta Gerwig’s presentation of modern, intersectional feminism. Secondly, Keira Moore reflects on the invisibility Black and Brown women face in relation to their lived experiences in the modern world of “color blindness” and the insidious new face of American racism. Next, Maya Revell questions how the film’s portrayal of humanity relies on the exclusion of Black and Brown people, particularly women, and their experiences in the world. The authors conclude by emphasizing the film's denouement and advocating for a more realistic and impartial perspective, enabling readers to envision their own conclusion.

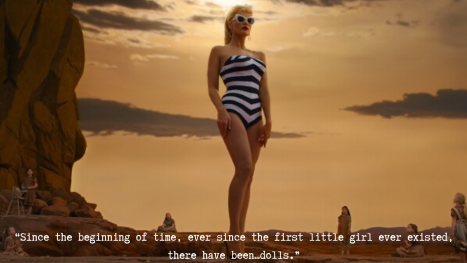

Image courtesy IMDB Media Index.

Alliyah’s standpoint

I cannot help but think that I am not the target viewer for Greta Gerwig’s Barbie. For birthdays and Christmases, I received Bratz dolls and their assortment of branded merchandise. Although I was only seven and did not wear heavy eye makeup and platformed, chunky boots, I still saw myself represented in the Bratz line-up (My favorite Bratz doll was Sasha, of course). I was not a Barbie girl. So when the Barbie movie was initially announced, I was appropriately disinterested. During premiere week, social media was buzzing with fans expressing having already seen it multiple times and commentary on how its profound and thought-provoking messages moved them to tears. With its bold marketing and pink merchandising, the movie became hard to ignore, and I wanted to know what all the hype was about.

The opening scene of Barbie pays homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey. In a desolate wasteland, little girls are playing with baby dolls, while the narrator remarks that this has been common since the beginning of time. Suddenly, a giant, original 1959 version of Barbie (Margot Robbie) in a black and white striped swimsuit appears, leaving the children in awe. In fits of rejection, they destroy and throw away their baby dolls. Rightfully so—who wouldn’t want a new toy? But visibly missing from the scene are racially marginalized little girls, specifically Black girls. Given the dramatic start of the film, I began to wonder if this erasure or exclusion of little Black girls was intentional. The broader social context in which the movie was written and produced focuses on the issues and experiences of white, middle-class women, often neglecting or downplaying the unique struggles faced by women of color and other marginalized groups. From the film’s start, are we expected to take note of exclusion? Is this film meant to critique white feminism and, therefore, itself? I went into the theater apprehensive about supporting a feminist culture icon, and this opening scene set the tone for further exploration of the intentional lack of intersectionality in Barbie’s world and beyond.

Keira: “Alliyah, thank you for sharing. You bring up a good point in referencing the intentionality of the film. Can you further explain what other movie elements suggest that it intentionally disregards racial boundaries, thus providing an unrealistic portrayal of present society?”

To gain a deeper understanding of the intentionality of a film and what filmmakers aim to achieve, there are crucial elements to examine. Analyzing a film’s plot and storyline helps us understand the central narrative and its themes. What message is the film trying to convey? Is it focused on character development, a specific event, or a broader social issue? In this case, the Barbie movie offered a surface-level critique of patriarchy and an entry-level introduction to feminism. Not surprisingly, it used the core tenets of white feminism to critique the patriarchy. There was no intersectional offering of how patriarchy affects the most marginalized in our society. Sasha's monologue is the only sprinkle of pushback towards society as a whole. She expresses how Barbie's existence has “...set the feminist movement back fifty years,” even mentioning how Barbie is a fascist who represents unrealistic beauty standards.

Barbie was not a grand societal critique. The time period, social issues, and cultural influences shape a film's intention and relevance. We must consider how the film engages with its intended audience. Is it meant to entertain, provoke thought, elicit emotion, or challenge viewers? The intended audience and their reactions can reveal a film's purpose. In the real world, outside of Gerwig’s speculative Barbie Land, marginalized women, girls, and non-binary people levy criticism on white women and their feminist beliefs, values, and ideologies. To engage with intersectionality, the movie would have also had to critique white feminism. Therefore, the premise of the movie would not have worked. After its release, women, especially young white women, praised this film as the latest feminist Magnus Opus. I, however, could have stayed home. But at least the popcorn was delicious.

Barbie was not a grand societal critique. The time period, social issues, and cultural influences shape a film's intention and relevance. We must consider how the film engages with its intended audience. Is it meant to entertain, provoke thought, elicit emotion, or challenge viewers? The intended audience and their reactions can reveal a film's purpose. In the real world, outside of Gerwig’s speculative Barbie Land, marginalized women, girls, and non-binary people levy criticism on white women and their feminist beliefs, values, and ideologies. To engage with intersectionality, the movie would have also had to critique white feminism. Therefore, the premise of the movie would not have worked. After its release, women, especially young white women, praised this film as the latest feminist Magnus Opus. I, however, could have stayed home. But at least the popcorn was delicious.

Image courtesy IMDB Media Index.

Image courtesy IMDB Media Index. Keira’s standpoint

Growing up as a little Black girl in the South, I vividly remember being exposed to the actual Barbie doll. It was an unspoken shared belief that these dolls represented beauty and feminine standards. They were mothers; they cooked and cleaned. They were well-dressed, well-kempt, and nested in this ideology of perfection. Also, most of the time, they were white women. My perception was shaped by Barbie’s supposed representation of the epitome of beauty. At one point, I thought the term “Barbie doll” applied to all dolls. It wasn’t until my introduction to a Bratz doll and its racial diversity that I became aware that dolls (and people) do not have to adhere to conventional American beauty standards. Bratz dolls impacted my Black childhood viewpoint and those of other racially disparate children.

That said, I was reluctant to see Barbie, as it honestly held little importance to me and my Black identity. Against my own judgment, I took myself on a solo date to see Barbie. Initially, I stood out like a sore thumb. I was the only Black woman in the theater, AND I didn’t wear pink (oops). As I watched the movie, I shifted through an array of emotions, with one sticking out to me the most: feeling left out. Like with pop culture phenomena implicit aimed at a white consumer audience, “I can’t relate to this,” I would think to myself. My Blackness and my experiences were invisible in this film, which I saw as perpetuating new/modern racism and colorblind narratives.

To provide context, Sniderman defines new racism is subtle, less abrasive, and more appealing, as race is not the center of marginalized disparities. [8] The term ‘new’ in this context signifies evolving methods of discrimination that are more convert and systemic compared to the historical overt forms of racism (i.e., colonialism, slavery, and Jim Crow Laws). This is evident in America Ferrera’s “empowering” monologue. The focus relied heavily on the gender binary, man and woman, with no acknowledgment of race, a component that has molded my own [Black] daily experiences. America begins by saying, “It is literally impossible to be a woman.” But what kind of woman? The narrator states, “Barbie is all these women. And all these women are Barbie.” The grouping of all women’s lived experiences is inaccurate and controversial. Moreover, the movie's white racial framing persistently challenges racial boundaries by unintentionally asserting that all women, irrespective of their intersectional identities, are fundamentally homogeneous.

Maya: “Thank you for sharing your experience, Keira. Your focus on new racism prompts me to consider how different experiences of oppression can be weaponized to silence the experiences of other communities, particularly those with intersectional identities. This dynamic occurs significantly between white feminism and feminist theories from women and queer people of color. Could you elaborate on the tensions within America Ferrera’s monologue?”

Upon revisiting America Ferrera's (Gloria's) monologue, I pondered the question I stated earlier, "What kind of woman?". In an attempt to derive a fresh significance from this piece, I added the term "Black" before "woman," resulting in the statement, "It is literally impossible to be a [Black] woman." Although this resonated with me on a personal level, I am aware that the film's original statement conflicts with my own principles, as it disregards the intentional neglect of my racial identity and forces me to align my experiences with those of all other women.

A common recurring theme in this film and all media exposure is disregarding the significance of race. Wilson argued in 1980 that race essentially was no longer an extreme determining factor in the lived experiences of Black Americans. [9] This assertion runs parallel to colorblindness and modern ideologies of racism. Moreover, this simplistic mindset has been contradicted by the realities individuals are confronting in the 2020s. Consequently, this monologue ignores how oppressive structures perpetuate unequal power dynamics, thus silencing the voices of marginalized communities (in this specific context, Black women). Black women have been viewed through an intersectional lens as individuals who experience the “double burden” of gendered racism. [10] American culture and society continue to expand upon its foundation of institutionalized marginalization. While this film (intentionally or unintentionally) mirrors society, the apparent aggregation of women’s experiences as all women’s experiences is not only ignorant but irresponsible, as this film is attempting to encompass the manifestations of inequality that persist in America.

A common recurring theme in this film and all media exposure is disregarding the significance of race. Wilson argued in 1980 that race essentially was no longer an extreme determining factor in the lived experiences of Black Americans. [9] This assertion runs parallel to colorblindness and modern ideologies of racism. Moreover, this simplistic mindset has been contradicted by the realities individuals are confronting in the 2020s. Consequently, this monologue ignores how oppressive structures perpetuate unequal power dynamics, thus silencing the voices of marginalized communities (in this specific context, Black women). Black women have been viewed through an intersectional lens as individuals who experience the “double burden” of gendered racism. [10] American culture and society continue to expand upon its foundation of institutionalized marginalization. While this film (intentionally or unintentionally) mirrors society, the apparent aggregation of women’s experiences as all women’s experiences is not only ignorant but irresponsible, as this film is attempting to encompass the manifestations of inequality that persist in America.

Image courtesy IMDB Media Index.

Maya’s standpoint

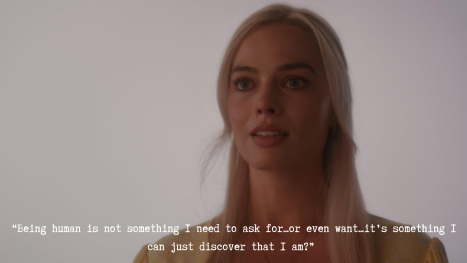

At the moment that Barbie asked if becoming human was just a process of discovery, I felt the tension in my hands subside. It was not that I was satisfied with the movie; it was quite the opposite. Instead, this moment validated my initial expectations of how questions of what it means to be human would play out in the theater. Coming into the movie, I was still determining what to expect from Barbie. I had never been into Barbie growing up. Still, the barrage of media coverage and testimonials from viewers and friends who felt that Barbie was “the movie of our time” and a “true and complex representation of feminism” persuaded me to go. Throughout the film, I made note of the film’s contradictory stances on environmental and climate degradation and its predictable turn toward Black and Brown women artists and entertainers to promote the movie. However, I was disturbed by this notion that “being human” is just a matter of self-actualization through simplistic visual representations of empathy, joy, and delight. Why must we turn away from feelings of anger, rage, and grief in our descriptions of humanity? How does this turn dismiss the work of Black and Brown feminists who have long described rage and anguish as productive for establishing ethical solidarities, building empathy across lines of difference, and working against white supremacy and racial capitalism. [11][12][13]

I was not expecting an intersectional engagement, a discussion of anti-Blackness or anti-Indigeneity, but this scene felt too predictable. Instead of this aim to center a utopian vision of feminism through Stereotypical Barbie, I wonder what new possibilities could be opened and what alternative discourses could be taken up through an engagement with the ongoing entanglements of anti-Indigeneity, anti-Blackness, and climate and ecological degradation. As I looked around the theater at the (white) bodies crying, cheering, and clapping at the screen, I felt my stomach churn.

Alliyah: “I love all of this, Maya. You mention taking ‘note of the film’s contradictory stances on environmental and climate degradation.’ Can you further discuss how this plays out in the movie? And what would an acknowledgment of this degradation look like in Barbie Land, or in Gerwig’s world-building?”

Early in the film, viewers watch Lawyer Barbie make a compelling argument that corporations are not people and thus should be held liable for the damages and impacts of their practices. I completely agree with this and recognize that the film did little to acknowledge Mattel’s own historical and ongoing environmental/climate impacts. While the film did bring in discontinued Barbies to show their missteps in terms of feminism, such as the pregnant Barbie, Video Girl Barbie, and the satirical Sugar Daddy Ken, it disregarded Mattel’s environmental sustainability errors, such as past issues with deforestation and plastic pollution. I question what it would look like for Barbie to present these environmental stories alongside their narratives of

Barbie is transformative. Engaging with the work of Indigenous, Black, and Decolonial feminisms as well as intersectional eco-feminisms can enable a generative read of Mattel as a corporation while also pointing out the limitations of any sustainability discourse that does not view colonialism and anti-Blackness as central to the issues of ecological degradation.

“Humans Only Have One Ending. Ideas Live Forever”

As three Black women, we are familiar with having our stories written for us and our images controlled. We have not been afforded access, forcing us to fight for representation and the accurate storytelling of our experiences. Barbie, a film that centers on femininity and womanhood, has misrepresented the Black woman by situating the story in systemic frameworks of subjugation. Regardless of intentionality, Black women, and other racially marginalized women, may view this film with slight resentment and distaste. We took advantage of our ability to create freely and embarked on the task of reimaging the Barbie ending. This allows for us to reconceptualize, for alternative narratives to unfold, and for new resolutions to take shape.

Here, we used the first half of the original transcript of the ending of Barbie in which she becomes human. We felt this was a vital point in the film’s ending for the narrative to be modified. That said, we focused on real-life situations that drastically impact Black and Brown women’s lives. This reiteration allows space for subjectivity and for the reader to create their own personal and realistic ending.

Barbie: So, being human’s not something I need to… ask for or even want? I can just…It’s something that I just discover I am?

Ruth: I can’t in good conscience let you take this leap without you knowing what it means.

Take my hands.

Now close your eyes.

[wind blowing]

[pensive music playing]

Now feel.

[wind blowing]

[Interspersed visuals flash on the screen:

A young child gleefully blowing bubbles.

The scene pans out to communities of people vehemently protesting the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade with “Black Lives Matter” chanting in the background.

As the audio and visual fade out, Barbie sees a scene of a newborn crying while a family rejoices. The scene is abruptly replaced by a similar scene—this time, a Black family mourns as the rates of Black maternal mortality rate across the screen.

The sounds of crying reduce, and the scene pans to a series of news headlines of the Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

As the headlines fade, the scene shifts between interviews and images of women organizing and mobilizing against the Supreme Court and supporting reproductive justice. Parallel to this scene, we see Black and Brown women hosting community-wide mutual aid events.

The scene zooms in, darkens, and begins to ripple. Barbie sees a pod of Orca whales swimming through the Pacific Ocean.

As the pod disappears from the screen, images of wildfires, massive flooding, and smoke are layered over and across the image. Abruptly, media images of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk appear with “Space Race” as the headline.

Finally, the visuals go completely black.

Slowly, different faces appear and multiply on the screen. Flashing across the screen are visuals of people—of all races and ethnicities—having varied experiences: joyful, mourning, angry, laughing, loving, nostalgic, frustrated, numb, lonely, content, and grieving.

Silence.]

Black Feminist Narrator: Barbie did not see herself presented in those images. She is confused and has no idea how to navigate her experiences as a white woman, especially with this new acknowledgment of her identity.

[Barbie hesitates]

Barbie: I… How do I fit into this? Is this my reality, too?

Ruth: Barbie, this is the real world, and these are tangible realities. Now that you know, it is up to you to make a conscious decision.

Black Feminist Narrator: So, Barbie was left questioning her position in the current American society as “stereotypical Barbie.” Will she decide to sacrifice her pink, feminist utopia for the unparalleled horrors of America or continue to bask in Barbie Land?

Barbie is transformative. Engaging with the work of Indigenous, Black, and Decolonial feminisms as well as intersectional eco-feminisms can enable a generative read of Mattel as a corporation while also pointing out the limitations of any sustainability discourse that does not view colonialism and anti-Blackness as central to the issues of ecological degradation.

“Humans Only Have One Ending. Ideas Live Forever”

-Ruth Handler

As three Black women, we are familiar with having our stories written for us and our images controlled. We have not been afforded access, forcing us to fight for representation and the accurate storytelling of our experiences. Barbie, a film that centers on femininity and womanhood, has misrepresented the Black woman by situating the story in systemic frameworks of subjugation. Regardless of intentionality, Black women, and other racially marginalized women, may view this film with slight resentment and distaste. We took advantage of our ability to create freely and embarked on the task of reimaging the Barbie ending. This allows for us to reconceptualize, for alternative narratives to unfold, and for new resolutions to take shape.

Here, we used the first half of the original transcript of the ending of Barbie in which she becomes human. We felt this was a vital point in the film’s ending for the narrative to be modified. That said, we focused on real-life situations that drastically impact Black and Brown women’s lives. This reiteration allows space for subjectivity and for the reader to create their own personal and realistic ending.

Alternative ending

Barbie: So, being human’s not something I need to… ask for or even want? I can just…It’s something that I just discover I am?

Ruth: I can’t in good conscience let you take this leap without you knowing what it means.

Take my hands.

Now close your eyes.

[wind blowing]

[pensive music playing]

Now feel.

[wind blowing]

[Interspersed visuals flash on the screen:

A young child gleefully blowing bubbles.

The scene pans out to communities of people vehemently protesting the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade with “Black Lives Matter” chanting in the background.

As the audio and visual fade out, Barbie sees a scene of a newborn crying while a family rejoices. The scene is abruptly replaced by a similar scene—this time, a Black family mourns as the rates of Black maternal mortality rate across the screen.

The sounds of crying reduce, and the scene pans to a series of news headlines of the Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe v. Wade.

As the headlines fade, the scene shifts between interviews and images of women organizing and mobilizing against the Supreme Court and supporting reproductive justice. Parallel to this scene, we see Black and Brown women hosting community-wide mutual aid events.

The scene zooms in, darkens, and begins to ripple. Barbie sees a pod of Orca whales swimming through the Pacific Ocean.

As the pod disappears from the screen, images of wildfires, massive flooding, and smoke are layered over and across the image. Abruptly, media images of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk appear with “Space Race” as the headline.

Finally, the visuals go completely black.

Slowly, different faces appear and multiply on the screen. Flashing across the screen are visuals of people—of all races and ethnicities—having varied experiences: joyful, mourning, angry, laughing, loving, nostalgic, frustrated, numb, lonely, content, and grieving.

Silence.]

Black Feminist Narrator: Barbie did not see herself presented in those images. She is confused and has no idea how to navigate her experiences as a white woman, especially with this new acknowledgment of her identity.

[Barbie hesitates]

Barbie: I… How do I fit into this? Is this my reality, too?

Ruth: Barbie, this is the real world, and these are tangible realities. Now that you know, it is up to you to make a conscious decision.

Black Feminist Narrator: So, Barbie was left questioning her position in the current American society as “stereotypical Barbie.” Will she decide to sacrifice her pink, feminist utopia for the unparalleled horrors of America or continue to bask in Barbie Land?

Notes: Hi, Barbie!

[1] In efforts to maintain our decolonial agenda, the authors intentionally do not captialize the “w” in white. However, the “b” in Black is capitalized to challenge the historical dehumanization of a marginalized group we are a part of and to highlight that Black and Blackness serve as proper nouns.

[2] Sessoms, J. (2023, August 2). ‘Barbie’s revival of Hyper Femininity is the ultimate act of feminism,’ L’Officiel USA. https://www.lofficielusa.com/fashion/barbie-hyper-femininity-ultimate-act-of-feminism-coquettecore-bimbocore

[3] Haraway, D. (1988) ‘Situated knowledge: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective,’ Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 575–600

[4] Hill Collins, P. (1990) Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Empowerment and the Politics of Consciousness. London: Unwin Hyman

[5] Reynolds, T. (2002) Re-thinking a black feminist standpoint, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 25:4, 591-606, DOI: 10.1080/01419870220136709

[6] O’Neill, C. (2021). ‘Towards an Afrofuturist Feminist Manifesto,’ In: Butler, P. (eds) Critical Black Futures. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-7880-9_4

[7] Kilgore, D. (2020). ‘This Time for Africa! Afrofuturism as Alternate (American) History,’ in Literary afrofuturism in the twenty-first century. Essay, The Ohio State University Press.

[8] Sniderman, P. M., Piazza, T., Tetlock, P. E., & Kendrick, A. (1991). “The new racism,” American Journal of Political Science, 423-447

[9]Wilson, J.W., (1980). The Declining Significance of Race: Blacks and Changing American Institutions. University of Chicago Press.

[10] Jean, Y. S., & Feagin, J. R. (1997). Double Burden: Black Women and Everyday Racism. ME Sharpe.

[11] Lorde, A. (1981). ‘Keynote Address: The NWSA Convention. The Uses of Anger,’ Women's Studies Quarterly 9, no. 3 (1981): 7–10.

[12] King, T. L. (2019). The Black Shoals: Offshore Formations of Black and Native Studies. Duke University Press.

[13] Nash, J. C., & Pinto, S. (2021). ‘A new genealogy of “Intelligent rage,” or other ways to think about white women in feminism,’ Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 46(4), 883–910. https://doi.org/10.1086/71329

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics