Sarah Javaid, a graduate of the Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, Lahore, is an Assistant Professor at her alma mater. Her research interests focus on exploring youth subcultures in contemporary Pakistan. Her work seeks to understand fashion as an influencer of societal shifts, exploring how designers can respond to and shape these dynamics while mediating industry standards and expectations.

Syed Meher Ali is a contemporary Pakistani artist whose practice sits at the intersection of performance and decolonial expression. Situated in domestic settings, his work challenges social structures and reclaims fashion as a site of agency and cultural legitimacy

Over the last fifteen years, global fashion studies have made strides toward decolonization. We see this in updated course syllabi, museum exhibitions, conference themes, and fashion weeks showcasing non-Western designers. The institutions that once claimed fashion now aim to decolonize it. [1] The power struggle that emerges from the Western positioning of this narrative divides us. [2] This tension feels especially acute in Pakistan, where colonial legacies, ideological anxieties, and social surveillance still shape our sartorial histories. Here, ‘sartorial’ refers to the embodied, situated practice of dress through which social meaning is made, contested, and archived. Grounded in indigenous iconography and craft, it reframes what dress does and signifies. [3] This reflection, therefore, examines the sartorial both as an object of analysis and a method of decolonization. It proposes how sartorial practice can restore authorship to Pakistani makers and wearers, offering a transferable framework for contemporary fashion pedagogy and practice.

I write as an educator at Pakistan’s first fashion school, Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design (PIFD). Established in 1994 as a project of the Export Promotion Bureau and initially affiliated with L’Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, PIFD imported not only a curriculum but an aesthetic. [4] This foundation structured how fashion would be taught across Pakistan, with local institutes soon following suit. Even after its recognition as a degree-awarding institution by the Higher Education Commission in 2010, Western fashion continued to dominate classrooms, while non-Western garments appeared largely as ethnic curiosities.

As a PIFD graduate, and later a faculty member, I observed that the curriculum privileged Western practices, often steering students towards Eurocentric themes in their design process. Assessing this gap in the teaching of fashion prompted me to redesign two undergraduate courses. The first explored the history of South Asian costume and indigenous textiles, while the second investigated Pakistan’s sartorial identity during and after Partition. These courses offered accounts of how culture informed the politics of dress. However, resources were limited. What I had were fragmented archives and personal anecdotes. Designing these courses revealed how deeply the term fashion had been misconstrued and underscored the urgency of acknowledging and documenting local histories. This urgency found meaning in the work of students like Syed Meher Ali, whose practice exemplifies how pedagogical intervention can seed new sartorial inquiries.

The absence of historical data and material culture has reinforced a predominantly Western approach to teaching fashion in Pakistan. As a result, indigenous histories are regularly marginalized, flattening our cultural complexity. [5] A reframed approach treats local dress not as a static national symbol but as an evolving situated practice that embodies stories of aspirations, craft, faith, migration, and kinship. When students explore local archives—like stories of their grandmothers’ bridal joras, or the houses they lived in post-Partition, or how the children on the street style their secondhand garments—they learn that fashion thrives in bazaars, rituals, and everyday life, and that these practices constitute the knowledge base of fashion studies.

I write as an educator at Pakistan’s first fashion school, Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design (PIFD). Established in 1994 as a project of the Export Promotion Bureau and initially affiliated with L’Ecole de la Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne, PIFD imported not only a curriculum but an aesthetic. [4] This foundation structured how fashion would be taught across Pakistan, with local institutes soon following suit. Even after its recognition as a degree-awarding institution by the Higher Education Commission in 2010, Western fashion continued to dominate classrooms, while non-Western garments appeared largely as ethnic curiosities.

As a PIFD graduate, and later a faculty member, I observed that the curriculum privileged Western practices, often steering students towards Eurocentric themes in their design process. Assessing this gap in the teaching of fashion prompted me to redesign two undergraduate courses. The first explored the history of South Asian costume and indigenous textiles, while the second investigated Pakistan’s sartorial identity during and after Partition. These courses offered accounts of how culture informed the politics of dress. However, resources were limited. What I had were fragmented archives and personal anecdotes. Designing these courses revealed how deeply the term fashion had been misconstrued and underscored the urgency of acknowledging and documenting local histories. This urgency found meaning in the work of students like Syed Meher Ali, whose practice exemplifies how pedagogical intervention can seed new sartorial inquiries.

The absence of historical data and material culture has reinforced a predominantly Western approach to teaching fashion in Pakistan. As a result, indigenous histories are regularly marginalized, flattening our cultural complexity. [5] A reframed approach treats local dress not as a static national symbol but as an evolving situated practice that embodies stories of aspirations, craft, faith, migration, and kinship. When students explore local archives—like stories of their grandmothers’ bridal joras, or the houses they lived in post-Partition, or how the children on the street style their secondhand garments—they learn that fashion thrives in bazaars, rituals, and everyday life, and that these practices constitute the knowledge base of fashion studies.

I was introduced to Meher as his instructor at PIFD (2018–2022), where I supervised the studio course in which he first invited a dialogue on the social construct of fashion. By investigating gendered hierarchies through the act of dressing, his inquiry extended beyond coursework into a sustained sartorial practice that revealed how the semiotics of dress are shaped by hegemonic structures. Since his graduation, successive student cohorts have cited his approach, drawing courage to foreground indigenous materials, craft, domestic objects, and gender nuance in their projects. Contemporary Pakistani designers have likewise adapted this template across product development, casting, and brand storytelling. I therefore select Meher not for symbolic resonance but because his practice demonstrates how decolonization operates as a repeatable design framework within Pakistan. It is legible to local audiences, adaptable by emerging designers, and capable of shifting classroom and studio practice toward a reclaimed authorship.

Middle: Adornment as ritual in heirloom pieces by Mughal Jewelers, 2025.

Bottom: Codes of hybridity, Sidha Paijama and leather jacket, 2025. All images courtesy of Syed Meher Ali.

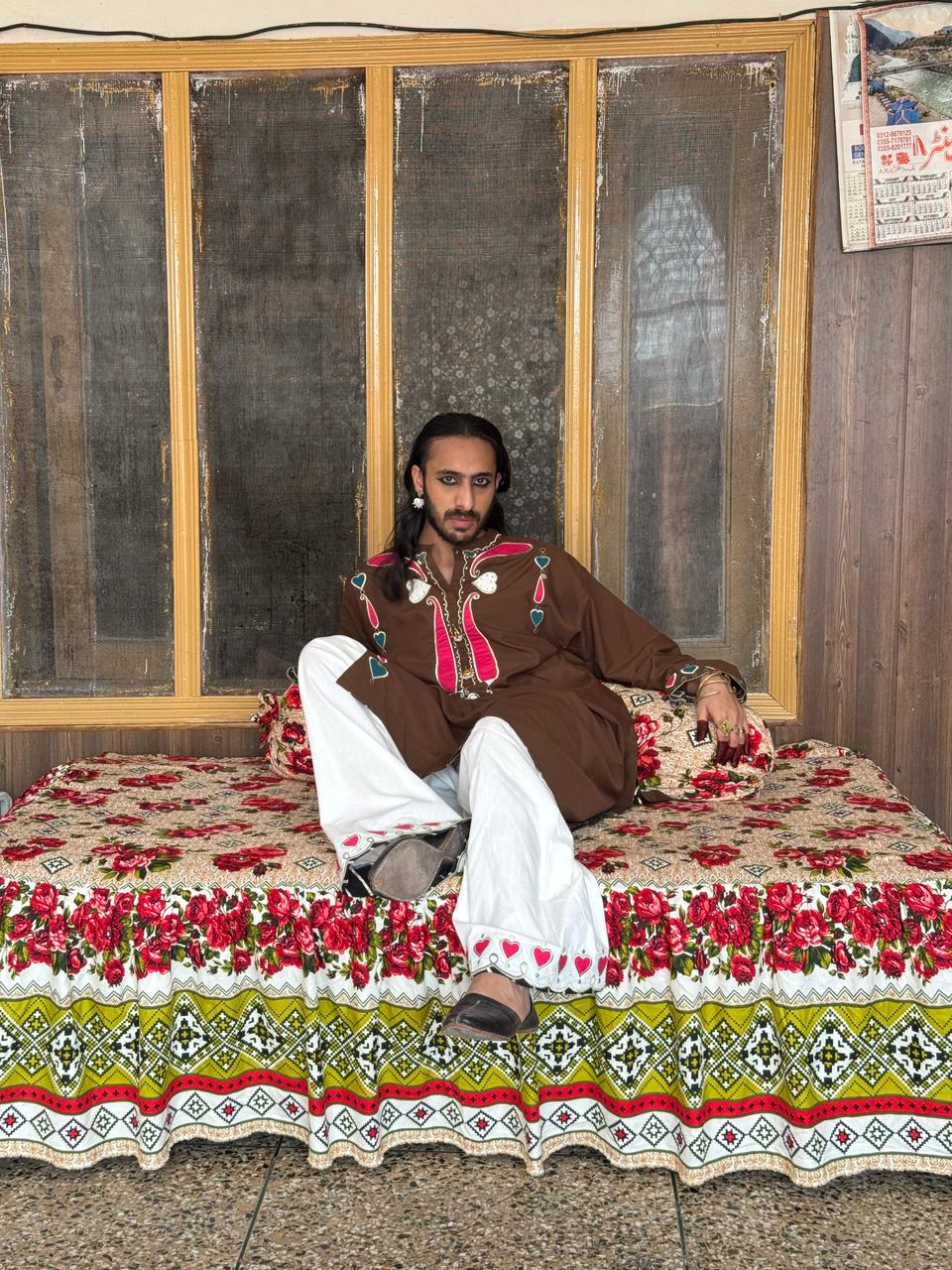

His work also makes visible how deeply symbols can guide personal aesthetics. For Meher, the heart motif holds deep resonance. Borrowed from his mother’s green silk garara, embroidered with stars, moon, and hearts, the garment burned in a house fire, but its memory endured. Some dismissed his obsession with hearts as a poor sentimental token. But, for him, they became an act of remembrance. Transposing these deliberate choices—including the kohl-inked eyes, draped shalwar, paranda, and the use of Kashmiri jewelry—becomes an emblem of memory and resistance. His style, deeply embedded in regional traditions, extends beyond ceremonial contexts, asserting that the legitimacy of adornment is not inherently tied to ritualistic or heteronormative conventions. In urban encounters, he was often cast as a threat to the social order, met with ridicule and labeled uncivilized. These responses reveal how hierarchies of taste mark certain expressions as inferior, shaping dominant notions of cultural authenticity.

Dil Kurta for Eid, 2025. Image courtesy of Syed Meher Ali.

Dil Kurta for Eid, 2025. Image courtesy of Syed Meher Ali.Resisting such relegation, Meher invites the viewer inside an ordinary domestic setting characterized by floral bedsheets, wooden windows, and bright paint. By situating fashion within a familiar Pakistani environment, Meher authenticates intimate spaces as legitimate realms for decolonized expression. Disrupting conventional norms, the use of traditional iconography is not merely nostalgic but a vibrant cultural reality often dismissed due to its ‘distasteful’ aesthetic against Western minimalism.

What we wear is often underestimated as a social force. We are so accustomed to clothing that it slips under the radar of our thoughts. Sometimes we conform to the expectations associated with the dress; other times we use it to help maintain social hierarchies and gender divisions. However, dress can also be mobilized to resist these establishments. Meher incorporates a multitude of such nuances in his work, provoking a sense of curiosity. Some find his practice disturbing. Some are shocked by the ease with which he extends his second skin. In the process of reclamation, Meher confronts these internalized hierarchies while offering others a space for collaborative intervention.

Second from top: Kashmiri Kurta with Sidha Paijama and tasseled dupatta, Shah Alam market, Lahore, 2025.

Second from bottom: Reclaiming local, in a green hand-loomed buti-weaved shalwar and paranda braided handbag, 2024.

Bottom: Dil-e-Nova mirror by master metalworkers at Iqbal Begum in Androon Lahore, 2025. All images courtesy of Syed Meher Ali.

Dress is a continuum of identity and self-presentation, through which we reflect on and challenge preconceived assumptions about boundaries and transgressions. The embodiment of personal narrative creates a textual and performative power—to select or suppress certain aspects of human experience. To prefer or downplay meanings, to give voice and body to identities not only visible, audible, and palpable, but also discussable. [6] This endorsement can bring a structural change to the individual’s way of seeing themselves and the social world that provides context for the individual’s life and experiences.

The turn toward the local is not a rejection of the global but a reclamation of agency. It reflects the systems we inhabit and the futures we imagine. For too long, non-Western aesthetics were mined by the global fashion industry without credit. Today, Pakistani creators assert authority over their traditions. Despite restraints, memory continues to guide us. Clothing relics passed through generations, textiles woven in regions cut off by borders act as archives of identity. Similarly, in moments of quiet defiance—a student choosing to work on reviving a dying regional craft, or a designer working with local artisans despite logistic concerns, or a garment reimagined from discarded family heirlooms—these are indigenous narratives that need to be recorded as they serve as an extension of the self and as future contributions to cultural history.

Reclaiming our sartorial practice is more than an academic exercise. It is a declaration of self-definition, resistance, and healing. When a student like Syed Meher Ali stands before a camera, he is demanding recognition of his sartorial identity. In Pakistan, where colonial scars and cultural erasure run deep, fashion can be both a battleground and a sanctuary. It is how we remember. It is how we resist. It is how we dream. As we look ahead, the next fifteen years of fashion studies in Pakistan must be written by those who live and breathe these narratives. We must be more than case studies. We must be co-authors of our stories, articulating our languages, on our terms. To reclaim fashion is, ultimately, to reclaim ourselves.

Notes: Reclaiming Sartorial Narratives

[1] Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton, eds., Fashion and Postcolonial Critique (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019).

[2] Kimberly A. Miller-Spillman, Andrew Reilly, and José Blanco F., The Meanings of Dress, 5th ed. (New York: Bloomsbury, 2024).

[3] Lipi Begum and Rohit K. Dasgupta, “Contemporary South Asian Youth Cultures and the Fashion Landscape,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 2, no. 1 (2015): 133–45.

[4] Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, “About,” accessed August 14, 2025, https://pifd.edu.pk/about.html.

[5] Uzma Siraj and Asghar Dashti, “Unveiling the Coloniality of Education: A Post-colonial Critique and Decolonizing of Education in Pakistan,” Asian Journal of Academic Research 5, no. 3 (Autumn 2024): 19–30.

[6] Jessica L. Neumann, “Fashioning the Self: Performance, Identity and Difference” (master’s thesis, University of Denver, 2011), https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/475/.

The turn toward the local is not a rejection of the global but a reclamation of agency. It reflects the systems we inhabit and the futures we imagine. For too long, non-Western aesthetics were mined by the global fashion industry without credit. Today, Pakistani creators assert authority over their traditions. Despite restraints, memory continues to guide us. Clothing relics passed through generations, textiles woven in regions cut off by borders act as archives of identity. Similarly, in moments of quiet defiance—a student choosing to work on reviving a dying regional craft, or a designer working with local artisans despite logistic concerns, or a garment reimagined from discarded family heirlooms—these are indigenous narratives that need to be recorded as they serve as an extension of the self and as future contributions to cultural history.

Reclaiming our sartorial practice is more than an academic exercise. It is a declaration of self-definition, resistance, and healing. When a student like Syed Meher Ali stands before a camera, he is demanding recognition of his sartorial identity. In Pakistan, where colonial scars and cultural erasure run deep, fashion can be both a battleground and a sanctuary. It is how we remember. It is how we resist. It is how we dream. As we look ahead, the next fifteen years of fashion studies in Pakistan must be written by those who live and breathe these narratives. We must be more than case studies. We must be co-authors of our stories, articulating our languages, on our terms. To reclaim fashion is, ultimately, to reclaim ourselves.

Notes: Reclaiming Sartorial Narratives

[1] Elke Gaugele and Monica Titton, eds., Fashion and Postcolonial Critique (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019).

[2] Kimberly A. Miller-Spillman, Andrew Reilly, and José Blanco F., The Meanings of Dress, 5th ed. (New York: Bloomsbury, 2024).

[3] Lipi Begum and Rohit K. Dasgupta, “Contemporary South Asian Youth Cultures and the Fashion Landscape,” International Journal of Fashion Studies 2, no. 1 (2015): 133–45.

[4] Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, “About,” accessed August 14, 2025, https://pifd.edu.pk/about.html.

[5] Uzma Siraj and Asghar Dashti, “Unveiling the Coloniality of Education: A Post-colonial Critique and Decolonizing of Education in Pakistan,” Asian Journal of Academic Research 5, no. 3 (Autumn 2024): 19–30.

[6] Jessica L. Neumann, “Fashioning the Self: Performance, Identity and Difference” (master’s thesis, University of Denver, 2011), https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/475/.

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics