Carlos is an art director and fashion buyer focused on the synergies between retail reality and e-commerce. He has worked for major Italian fashion luxury brands like La Perla and Max Mara. Currently, Carlos as a fashion consultant develops 360° bespoke strategies such a trend forecasting, visual identity, image making, and digital development for brands like Bogner or Bulgari among many others.

As a professor of visual research and the future of fashion, Carlos makes younger generations reflect on the importance of the omnichannel paradigm and its upcoming drivers.

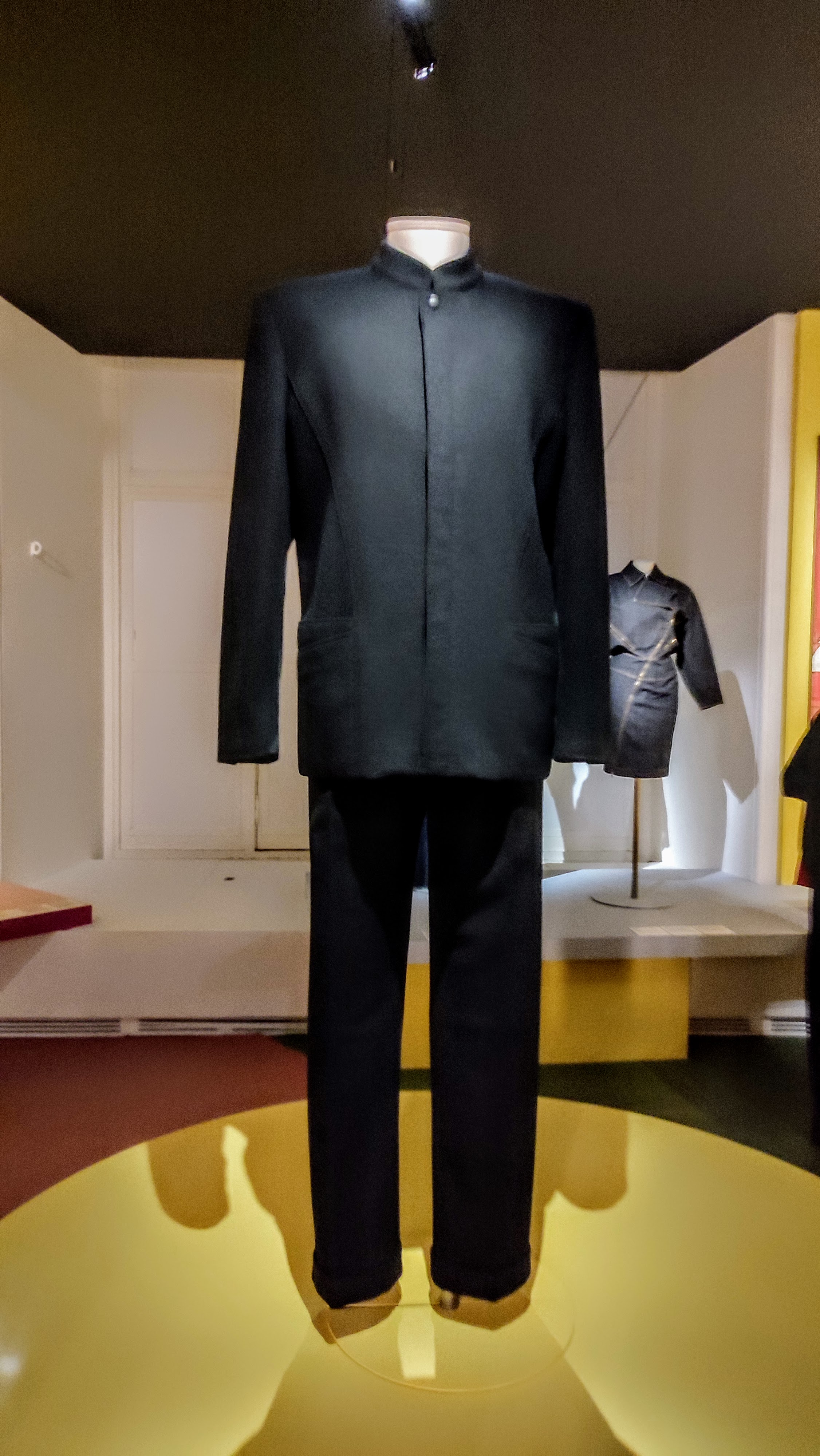

The rise of digital technology in the new millennium has influenced the creation of a production model based on efficiency. Before this technological revolution, some experiments in social control, such as the infamous Maoist revolution during the 1950s government of Mao Tse Tung, established the foundation for a new model of social oppression aimed at increasing the productivity of human and material resources. During Maoism, style homologation, understood as a form of social control imposed through the use of the Sun Yat-Sen jacket, became a tool not only for efficient production but also, and perhaps primarily, for ideological censorship. If we look at the fashion scene today, there is something unsettlingly similar to the Maoist concept and use of aesthetic homologation.

In Maoist China, aesthetic homologation was at the service of a standardized society. By leveling age groups, genders, and social classes, the regime was able to guarantee both exponential economic growth and social control over the Chinese population. The smaller the differences between people, the greater the productivity and the economic progress. After all, the visual expression of personal style (and of differences in general) ultimately tends to hinder economic growth by creating disjointed desires and ambitions, whereas the disciplined choice of the uniform speaks the visual language of socio-political power. In some ways, the imposition of the Sun Yat-sen jacket during Mao's regime is similar to the current model of consumerist homologation: a global and very simplified aesthetic code of street culture, ultimately evoking the culture of efficiency by producing less diversified garments (namely hoodies, jeans and t-shirts), which are then replicated and reproposed in similar fabrics and color variations. Inherently, the costs of design are reduced in favor of increasingly costly marketing tools, which are needed to differentiate one brand from another. For this same reason, in times of economic recession, ideologic flattening, and creative crisis, fashion - both as the mirror of society and as an industry aiming at continuous exponential growth - takes advantage of this aesthetic unification as a key driver to, once again, increase social control, boosting the efficiency of a system placed exclusively in the hands of a few very competitive giants who, in turn, dictate the market rules.

In post-modern society, the process of digitization has contributed to an aesthetic globalization by means of new consumption codes; both brands and consumers have shaped a new ideal of uniformity within the pleasure of being recognized by one another. A reassuring sense of taste dictates a “comfort-zone style” and encourages brands towards the convenience of a guaranteed turnover model. The more fashion puts itself at the service of digital consumption, the more creativity is ultimately delegated to the final consumers, who end up playing creative directors on social platforms that invite users to dress their virtual identities.

Today’s consumers are firmly convinced of their freedom of choice since, today more than ever, they tend to position themselves within like-minded groups or communities of values. This makes them feel that they can express themselves individually by buying what (they think) they are choosing autonomously. In truth, the manipulation of consumers’ desires is dictated by a super-object: technology, a dematerialized yet omnipresent form of control that ideally allows people to be their own creators while actually transforming them into “consumo ergo sum” individuals, approved by community rules. This creates a rather perverse sense of social media acceptance, aimed at manipulating individuals by means of a collective mentality dictated by what is photogenic and/or validated by followers and other virtual tech-friends.

As a consequence of the manipulation of creativity by the digital sphere, fashion becomes a blank canvas on which a new form of product is being designed, following commercial micro trends and social algorithms. While the fashion industry is supposedly discussing sustainability, a huge amount of influencers (plenty of them, at the same time) are wearing, one time only and discarding after use, ultra-expensive looks from luxury designers’ collections, transforming the perception of a long-term investment into a moment of digital glory: luxury has become fast fashion.

Brands cannot keep up with the quantity of content required by the day-to-day social media flow, nor with its rapid interchange, therefore, they tend to homologate their creative sphere by replacing ready-to-wear collections with a sort of “wardrobe” style container, which differs from the one proposed by other brands only because of its narrative, its testimonials, and the context in which it is showcased. No longer diversified by the products they offer but rather by the way in which said products are communicated, fashion collections have started embodying an accessible, understandable, and easily approachable world, thus becoming the expression of an industry in which many more people can, in theiry, feel included.

The new customer journey plays by the rules of Gen Z-ers, who tend to relate to brands in a more ideological, less product-centered way. Consequently, luxury is no longer synonymous with scarcity, quality, and style, but with everyday, aesthetically relatable, and generally “understandable” products, defined merely by a spectacular one-of-a-kind storytelling, by impressive site-specific installations, fashion films, or in-store performances aimed at creating a strong connection with the younger generation of consumers. Along this path, expressions of individual creativity are displaced, shifted towards the “wow effects” of a communication destined to escalate fashion to the next level of the luxury paradigm: social media lust.

Pucci's Mediterranean party in Capri, the Cappuccinos at Dior’s flagship boutique in Saint Tropez, or Bottega Veneta's Instagrammable pop-up store in South Korea, are all visually magnificent experiences that transport customers into an endless escape/travel mode. Luxury has always been a journey, but nowadays the itinerary is easier and cheaper as social networks provide virtual transportation; at the same time, imagining has become harder, because everything is always available and constantly on display.

When compared to emerging realities, established brands tend to perform better because their position as advertisers provides them with the power to capitalize upon consumers’ desires, dictating what people have to wear in order to follow the hype. These - very few - brands manage to monopolize and ultimately conform the fashion aesthetic, and it is undeniable that “seeing always the same looks, unchanged and unchanging, from the catwalk to magazines to celebs and influencers for the following six months, causes a flattening, a boredom, a homologation that is antithetical to the very nature of fashion.”[1]

![]()

1997 marked the beginning of the post-couture era. The fashion momentum of that time symbolized a turning point in the democratization of global aesthetics. The big luxury brands and their young and fresh creative directors, John Galliano at Dior and Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton just to name a few, changed the paradigm of luxury fashion houses. Brands became a contaminated container of disruptive ideas and theatrical fashion shows, where dreams were placed at the service of a very profitable merchandising policy: It-bags, fancy shoes and flamboyant accessories were designed to provide more democratic access to the exclusive world through relatively inclusive prices. This slow and incessant process helped fashion brands to achieve a multi-million-dollar turnover, as well as popularity worldwide .

Shortly after, the Aughts and the post-digitalization period of 2010 prompted the rebirth of several “sleeping brands” which were acquired by the oligopoly of conglomerates (for instance LVMH and Kering) and brought back to life by massive investments in image-making and communication strategies.

Luxury conglomerates promote a certain uniformity of style, logos, and aesthetic codes, while at the same time operating a new form of digital scarcity and pricing strategies oriented towards an inorganic economic development no longer based on product quality and craftsmanship but on marketing choices, fueling an ongoing desire for novelty. The current consumer, influenced by the immediacy of social media, is constantly looking for heavily-logoed items and blockbuster drop collections, following the new ethics of "real-time fashion." As mentioned before, this (d)evolution lacks the expression of individual creativity: from a human, social, and cultural perspective, this is clearly an issue.

Hyper-connectivity often evolves into digital voyeurism — a fetishistic ritual of pleasure deriving from a temporary identification of the viewer with the body being shown on the screen. Indeed, the idea of being aesthetically homologated to the rules set by society has had a serious impact in the realm of psychology; this manifests, for instance, with young people trying out the facial-symmetry filters on social media. One of the most emblematic scenarios is TikTok’s proposition of different face filters developed through the inversion of a mirror reflection, with the ultimate goal of revealing one’s face as others perceive it, imperfections and asymmetrical features included. One of the most popular symmetry effects is called “Inverted”. According to TikTok’s public view figures, the Inverted effect has been used in nearly 10 million videos and has reached 23 billion views. [2]

As a result of the pandemic, face-scrutinizing filters and apps are used more than ever, and the amount of time people spend in front of laptops and smartphone screens doing video calls has triggered an unforeseen increase in cosmetic surgery. [3] The rise in the number of (not only facial) reconstructive procedures by people who struggle to accept their appearance is known as the "Zoom Boom" effect; it was notified by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, estimating that “The pandemic has led to a 10% increase in cosmetic surgery countrywide. In France, despite limits on elective procedures during the pandemic, cosmetic surgeries are up by nearly 20%, estimates the French Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons.”[4] No need to say, the results of these cosmetic surgeries are hardly ever diverse, in fact, they tend to mirror one or another celebrity, ultimately erasing individual features and peculiarities. The exaggerated use of social media has led to the rise of new a aesthetic canon, a “virtual beauty” which, considering its non-material nature, is bound to be not only homologated but also distorted, thus leading to “deleterious effects on mental health caused by seeing yourself as others see you, and at the same time offering ways to cope with the new self-knowledge.” [5] In particular, in our hyper-sexualized society, more and more women tend to manipulate how they show themselves to others, "virtually modifying what they dislike, creating perfect selves instead."[6] The consequence of this social media syndrome has been defined as digitized dysmorphia, with the pressure for “normativity” and homologation exerted on the upcoming generations becoming ever greater.

![]()

Since fashion is inherently political, individuals tend to look for certain types of identifying style codes, status symbols, or statement pieces that will allow them to manifest their voice and express their opinion in an aesthetical manner. In every decade of the 19th century, clothes have had a strong connotation which reflected [or perhaps influenced) some kind of social movement: the 1950’s and the new role of femininity; the 1960’s and the new radicalism; the 1970’s and the strong political activism; the 1980’s and the rise of power dressing, and the 1990’s and its nihilistic grunge minimalism as the antithesis of 1980’s gloss. [7] After the year 2000, and even more so after the Covid-19 pandemic, fashion started speaking a global language, incorporating all human declarations into a conversation around style: by now, the fashion dialogue is fully political and it responds to the changes in the social structure and its certainties. New empowering messages are released every day according (mostly) to social media agendas, and ideology in all its forms becomes a driver of success for brands. Today, the ultimate recipe for success in the fashion universe is to buy communities of belief-driven consumers: these will naturally become ambassadors of brand values and creators of aspirational marketing content. Conversations around inclusivity also serve this purpose, and so does the fashion industry’s current broad-scale interest in gender fluidity: it isn’t just about respecting the rights of the LGTBQIA+ community, or offering inclusive beauty standards; it’s about changing the mindset of society in a very profitable way: the more people feel included in a homologated - and therefore deculturized - group, the more they are subjected to commercial exploitation. And fashion is the industry that has so far contributed the most to the transformation of the human being into consumer.

Fashion collections become more homogeneous, design is less creative, production costs are lower, and it's faster and easier to deliver messages to a larger number of potential hypebeast consumers.

Perhaps fashion is an industry that aspires not to create a diversity of identities, but to condense them into very few and similar groups of homologated individuals, controlling a globalized society by simplifying a low-cost and high-gain production model. What will happen next? Will we return to a veneration of the “less but best”, as some trend forecasters seem to hope? Will a new consciousness make consumers more aesthetically independent? Or will the huge fashion groups continue to dominate and impose a reassuringly homologated look? Personally, if fashion truly is a reflection of society, I fear that the next big trend will simply be a blatant expression of being “under control.”

Notes: Aesthetic Maoism

[1] Cecilia Caruso “Esiste ancora lo stile personale? Il feed degli influencer e le politiche dei brand raccontano un presente omologato e ripetitivo”. Nss Magazine ( April 8, 2022) https://www.nssmag.com/it/fashion/29487/stile-personale-influencer-marketing-brand

[2] Rhonda Garelick “When did we become so obsessed with being symmetrical? A slew of filters on social media allow users to evaluate their features , reigniting age-old obsessions with perfection and beauty”. New York Times (August 23, 2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/23/style/is-your-face-symmetrical.html

[3]The Economist . “Covid-19 is fuelling a zoom-boom in cosmetic surgery” (April 11, 2021) https://www.economist.com/international/2021/04/11/covid-19-is-fuelling-a-zoom-boom-in-cosmetic-surgery

[4] Cision PR Neswire “The Aesthetic Society releases annual statistics revealing significant increases in face, breast and body in 2021” (april 11, 2022) https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-aesthetic-society-releases-annual-statistics-revealing-significant-increases-in-face-breast-and-body-in-2021-301522417.html

[5] Rhonda Garelick “When did we become so obsessed with being symmetrical? A slew of filters on social media allow users to evaluate their features , reigniting age-old obsessions with perfection and beauty”. New York Times (August 23, 2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/23/style/is-your-face-symmetrical.html

[6] Isabelle Coy -Dibley “Digited Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image”. Palgrave Communications, Vol 2 (August 25, 2016) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2828637

[7] Maya Singer “ Power Dressing: charting the influence of politics on fashion”. Vogue.come (September 17, 2020) https://www.vogue.com/article/charting-the-influence-of-politics-on-fashion

Homologation dixit

In Maoist China, aesthetic homologation was at the service of a standardized society. By leveling age groups, genders, and social classes, the regime was able to guarantee both exponential economic growth and social control over the Chinese population. The smaller the differences between people, the greater the productivity and the economic progress. After all, the visual expression of personal style (and of differences in general) ultimately tends to hinder economic growth by creating disjointed desires and ambitions, whereas the disciplined choice of the uniform speaks the visual language of socio-political power. In some ways, the imposition of the Sun Yat-sen jacket during Mao's regime is similar to the current model of consumerist homologation: a global and very simplified aesthetic code of street culture, ultimately evoking the culture of efficiency by producing less diversified garments (namely hoodies, jeans and t-shirts), which are then replicated and reproposed in similar fabrics and color variations. Inherently, the costs of design are reduced in favor of increasingly costly marketing tools, which are needed to differentiate one brand from another. For this same reason, in times of economic recession, ideologic flattening, and creative crisis, fashion - both as the mirror of society and as an industry aiming at continuous exponential growth - takes advantage of this aesthetic unification as a key driver to, once again, increase social control, boosting the efficiency of a system placed exclusively in the hands of a few very competitive giants who, in turn, dictate the market rules.

In post-modern society, the process of digitization has contributed to an aesthetic globalization by means of new consumption codes; both brands and consumers have shaped a new ideal of uniformity within the pleasure of being recognized by one another. A reassuring sense of taste dictates a “comfort-zone style” and encourages brands towards the convenience of a guaranteed turnover model. The more fashion puts itself at the service of digital consumption, the more creativity is ultimately delegated to the final consumers, who end up playing creative directors on social platforms that invite users to dress their virtual identities.

| |

| Mao costume by Thierry Mugler 1985 displayed at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Paris. Photo taken Nov 28, 2022 by Carlos Gago Rodriguez. |

Socially manipulated consumers

Today’s consumers are firmly convinced of their freedom of choice since, today more than ever, they tend to position themselves within like-minded groups or communities of values. This makes them feel that they can express themselves individually by buying what (they think) they are choosing autonomously. In truth, the manipulation of consumers’ desires is dictated by a super-object: technology, a dematerialized yet omnipresent form of control that ideally allows people to be their own creators while actually transforming them into “consumo ergo sum” individuals, approved by community rules. This creates a rather perverse sense of social media acceptance, aimed at manipulating individuals by means of a collective mentality dictated by what is photogenic and/or validated by followers and other virtual tech-friends.

As a consequence of the manipulation of creativity by the digital sphere, fashion becomes a blank canvas on which a new form of product is being designed, following commercial micro trends and social algorithms. While the fashion industry is supposedly discussing sustainability, a huge amount of influencers (plenty of them, at the same time) are wearing, one time only and discarding after use, ultra-expensive looks from luxury designers’ collections, transforming the perception of a long-term investment into a moment of digital glory: luxury has become fast fashion.

Brands cannot keep up with the quantity of content required by the day-to-day social media flow, nor with its rapid interchange, therefore, they tend to homologate their creative sphere by replacing ready-to-wear collections with a sort of “wardrobe” style container, which differs from the one proposed by other brands only because of its narrative, its testimonials, and the context in which it is showcased. No longer diversified by the products they offer but rather by the way in which said products are communicated, fashion collections have started embodying an accessible, understandable, and easily approachable world, thus becoming the expression of an industry in which many more people can, in theiry, feel included.

The new customer journey plays by the rules of Gen Z-ers, who tend to relate to brands in a more ideological, less product-centered way. Consequently, luxury is no longer synonymous with scarcity, quality, and style, but with everyday, aesthetically relatable, and generally “understandable” products, defined merely by a spectacular one-of-a-kind storytelling, by impressive site-specific installations, fashion films, or in-store performances aimed at creating a strong connection with the younger generation of consumers. Along this path, expressions of individual creativity are displaced, shifted towards the “wow effects” of a communication destined to escalate fashion to the next level of the luxury paradigm: social media lust.

Pucci's Mediterranean party in Capri, the Cappuccinos at Dior’s flagship boutique in Saint Tropez, or Bottega Veneta's Instagrammable pop-up store in South Korea, are all visually magnificent experiences that transport customers into an endless escape/travel mode. Luxury has always been a journey, but nowadays the itinerary is easier and cheaper as social networks provide virtual transportation; at the same time, imagining has become harder, because everything is always available and constantly on display.

When compared to emerging realities, established brands tend to perform better because their position as advertisers provides them with the power to capitalize upon consumers’ desires, dictating what people have to wear in order to follow the hype. These - very few - brands manage to monopolize and ultimately conform the fashion aesthetic, and it is undeniable that “seeing always the same looks, unchanged and unchanging, from the catwalk to magazines to celebs and influencers for the following six months, causes a flattening, a boredom, a homologation that is antithetical to the very nature of fashion.”[1]

| Zara Man flagship store in Milan. Photo taken February 29, 2022 by Carlos Gago Rodriguez. |

Big, bang, spectacle!

1997 marked the beginning of the post-couture era. The fashion momentum of that time symbolized a turning point in the democratization of global aesthetics. The big luxury brands and their young and fresh creative directors, John Galliano at Dior and Marc Jacobs at Louis Vuitton just to name a few, changed the paradigm of luxury fashion houses. Brands became a contaminated container of disruptive ideas and theatrical fashion shows, where dreams were placed at the service of a very profitable merchandising policy: It-bags, fancy shoes and flamboyant accessories were designed to provide more democratic access to the exclusive world through relatively inclusive prices. This slow and incessant process helped fashion brands to achieve a multi-million-dollar turnover, as well as popularity worldwide .

Shortly after, the Aughts and the post-digitalization period of 2010 prompted the rebirth of several “sleeping brands” which were acquired by the oligopoly of conglomerates (for instance LVMH and Kering) and brought back to life by massive investments in image-making and communication strategies.

Luxury conglomerates promote a certain uniformity of style, logos, and aesthetic codes, while at the same time operating a new form of digital scarcity and pricing strategies oriented towards an inorganic economic development no longer based on product quality and craftsmanship but on marketing choices, fueling an ongoing desire for novelty. The current consumer, influenced by the immediacy of social media, is constantly looking for heavily-logoed items and blockbuster drop collections, following the new ethics of "real-time fashion." As mentioned before, this (d)evolution lacks the expression of individual creativity: from a human, social, and cultural perspective, this is clearly an issue.

Hyper-connectivity often evolves into digital voyeurism — a fetishistic ritual of pleasure deriving from a temporary identification of the viewer with the body being shown on the screen. Indeed, the idea of being aesthetically homologated to the rules set by society has had a serious impact in the realm of psychology; this manifests, for instance, with young people trying out the facial-symmetry filters on social media. One of the most emblematic scenarios is TikTok’s proposition of different face filters developed through the inversion of a mirror reflection, with the ultimate goal of revealing one’s face as others perceive it, imperfections and asymmetrical features included. One of the most popular symmetry effects is called “Inverted”. According to TikTok’s public view figures, the Inverted effect has been used in nearly 10 million videos and has reached 23 billion views. [2]

Virtual (distorted) beauty and digitized dysmorphia

As a result of the pandemic, face-scrutinizing filters and apps are used more than ever, and the amount of time people spend in front of laptops and smartphone screens doing video calls has triggered an unforeseen increase in cosmetic surgery. [3] The rise in the number of (not only facial) reconstructive procedures by people who struggle to accept their appearance is known as the "Zoom Boom" effect; it was notified by the American Academy of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, estimating that “The pandemic has led to a 10% increase in cosmetic surgery countrywide. In France, despite limits on elective procedures during the pandemic, cosmetic surgeries are up by nearly 20%, estimates the French Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons.”[4] No need to say, the results of these cosmetic surgeries are hardly ever diverse, in fact, they tend to mirror one or another celebrity, ultimately erasing individual features and peculiarities. The exaggerated use of social media has led to the rise of new a aesthetic canon, a “virtual beauty” which, considering its non-material nature, is bound to be not only homologated but also distorted, thus leading to “deleterious effects on mental health caused by seeing yourself as others see you, and at the same time offering ways to cope with the new self-knowledge.” [5] In particular, in our hyper-sexualized society, more and more women tend to manipulate how they show themselves to others, "virtually modifying what they dislike, creating perfect selves instead."[6] The consequence of this social media syndrome has been defined as digitized dysmorphia, with the pressure for “normativity” and homologation exerted on the upcoming generations becoming ever greater.

| Adidas x Gucci, 2022. |

From individuals to consumers

Since fashion is inherently political, individuals tend to look for certain types of identifying style codes, status symbols, or statement pieces that will allow them to manifest their voice and express their opinion in an aesthetical manner. In every decade of the 19th century, clothes have had a strong connotation which reflected [or perhaps influenced) some kind of social movement: the 1950’s and the new role of femininity; the 1960’s and the new radicalism; the 1970’s and the strong political activism; the 1980’s and the rise of power dressing, and the 1990’s and its nihilistic grunge minimalism as the antithesis of 1980’s gloss. [7] After the year 2000, and even more so after the Covid-19 pandemic, fashion started speaking a global language, incorporating all human declarations into a conversation around style: by now, the fashion dialogue is fully political and it responds to the changes in the social structure and its certainties. New empowering messages are released every day according (mostly) to social media agendas, and ideology in all its forms becomes a driver of success for brands. Today, the ultimate recipe for success in the fashion universe is to buy communities of belief-driven consumers: these will naturally become ambassadors of brand values and creators of aspirational marketing content. Conversations around inclusivity also serve this purpose, and so does the fashion industry’s current broad-scale interest in gender fluidity: it isn’t just about respecting the rights of the LGTBQIA+ community, or offering inclusive beauty standards; it’s about changing the mindset of society in a very profitable way: the more people feel included in a homologated - and therefore deculturized - group, the more they are subjected to commercial exploitation. And fashion is the industry that has so far contributed the most to the transformation of the human being into consumer.

Fashion collections become more homogeneous, design is less creative, production costs are lower, and it's faster and easier to deliver messages to a larger number of potential hypebeast consumers.

Perhaps fashion is an industry that aspires not to create a diversity of identities, but to condense them into very few and similar groups of homologated individuals, controlling a globalized society by simplifying a low-cost and high-gain production model. What will happen next? Will we return to a veneration of the “less but best”, as some trend forecasters seem to hope? Will a new consciousness make consumers more aesthetically independent? Or will the huge fashion groups continue to dominate and impose a reassuringly homologated look? Personally, if fashion truly is a reflection of society, I fear that the next big trend will simply be a blatant expression of being “under control.”

Notes: Aesthetic Maoism

[1] Cecilia Caruso “Esiste ancora lo stile personale? Il feed degli influencer e le politiche dei brand raccontano un presente omologato e ripetitivo”. Nss Magazine ( April 8, 2022) https://www.nssmag.com/it/fashion/29487/stile-personale-influencer-marketing-brand

[2] Rhonda Garelick “When did we become so obsessed with being symmetrical? A slew of filters on social media allow users to evaluate their features , reigniting age-old obsessions with perfection and beauty”. New York Times (August 23, 2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/23/style/is-your-face-symmetrical.html

[3]The Economist . “Covid-19 is fuelling a zoom-boom in cosmetic surgery” (April 11, 2021) https://www.economist.com/international/2021/04/11/covid-19-is-fuelling-a-zoom-boom-in-cosmetic-surgery

[4] Cision PR Neswire “The Aesthetic Society releases annual statistics revealing significant increases in face, breast and body in 2021” (april 11, 2022) https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/the-aesthetic-society-releases-annual-statistics-revealing-significant-increases-in-face-breast-and-body-in-2021-301522417.html

[5] Rhonda Garelick “When did we become so obsessed with being symmetrical? A slew of filters on social media allow users to evaluate their features , reigniting age-old obsessions with perfection and beauty”. New York Times (August 23, 2022) https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/23/style/is-your-face-symmetrical.html

[6] Isabelle Coy -Dibley “Digited Dysmorphia” of the female body: the re/disfigurement of the image”. Palgrave Communications, Vol 2 (August 25, 2016) https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2828637

[7] Maya Singer “ Power Dressing: charting the influence of politics on fashion”. Vogue.come (September 17, 2020) https://www.vogue.com/article/charting-the-influence-of-politics-on-fashion

Issue 15 ︎︎︎

Fashion & Southeast Asia

Issue 14 ︎︎︎

Barbie

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics

Issue 13 ︎︎︎ Fashion & Politics